Elevator pitch

In addition to regular marriage, Australia, Brazil, and 11 US states recognize common law (or de facto) marriage, which allows one or both cohabiting partners to claim, under certain conditions, that an informal union is a marriage. France and some other countries also have several types of marriage and civil union contracts. The policy issue is whether to abolish common law marriage, as it appears to discourage couple formation and female labor supply. A single conceptual framework can explain how outcomes are affected by the choice between regular and common law marriage, and between various marriage and civil union contracts.

Key findings

Pros

The availability of common law marriage in a jurisdiction is associated with lower teenage birth rates, especially among teenagers younger than 18 and among black teenagers.

When common law marriage is available married men participate more in the labor market.

The availability of common law marriage seems to be associated with more leisure time for married and cohabiting women, who spend one to two hours less per week in work outside the home.

Cons

Couple formation among college-educated men and non-college-educated women is discouraged when common law marriage is available.

The availability of common law marriage in the US and marriage under a community property contract in France discourages labor market participation of married and cohabiting women.

Where common law marriage is available, married and cohabiting women tend to spend more time in household work.

Author's main message

Laws regulating marriage and divorce have more economic and social implications than most policymakers realize. Common law marriage is no exception. Recognizing common law marriage affects couple formation, labor supply, and the decision to have children. These impacts appear to be related to what men and women can expect when they consider cohabitation. Policymakers may want to add the introduction or removal of marriage-related laws—such as common law marriage or choice between legal regimes for distributing assets in case of divorce—to the tools they use to influence labor supply, fertility, and related outcomes.

Motivation

In the US, states that recognize common law marriage offer residents a choice of ways to marry. Both common law marriages and regular marriages have the same legal implications for couples, including the need for a legal divorce to end the union. Some Australian states offer a similar choice, which is called a de facto relationship. Brazil also offers a choice between regular marriage and common law marriage.

Studies based on cross-state variation in the passage of no-fault divorce laws have shown that divorce laws influence such outcomes as couple formation, labor supply, and childbearing [2]. Cross-state variation in marriage laws is also expected to influence these outcomes, in part because of their implications for the dissolution of a marriage through divorce or death [3]. This paper looks at how, at the US state level, the availability of common law marriage affects these three outcomes. Couple formation is of policy interest because most research indicates that children raised by couples do better than children raised by a single parent [4]. Labor supply is an important engine of economic growth, and therefore policymakers need to understand how marriage laws might affect the labor supply of men and women. And decisions on whether to have children have repercussions for state budgets and long-term economic growth.

This paper also compares the effects of the availability of common law marriage on these outcomes with the effects of other choices of marriage type on the same outcomes in France. While common law marriage is not an option in France, couples can choose between two types of contracts for the division of property. Furthermore, the period after France introduced civil unions can be compared to an earlier period when regular marriage was the only type of official union. Civil unions were also introduced in Belgium, Ireland, and a number of other countries, but no studies could be found of their impact on the outcomes of interest here.

Discussion of pros and cons

Eleven US states still offer common law marriage as an additional way for heterosexual couples to organize their living-together arrangements. Four states fairly recently repealed laws recognizing common law marriage (Ohio in 1991, Idaho in 1996, Georgia in 1997, and Pennsylvania in 2005) [5]. Common law marriage does not require a marriage certificate or ceremony. It can be established when couples cohabit and one or both members of the couple announce themselves to be spouses by calling each other husband and wife in public, using the same last name, filing joint tax returns, or declaring their marriage on applications, leases, birth certificates, and other legal documents. It is possible for members of a couple to be considered legally committed to each other even without mutual consent if one of the parties claims to be in a common law marriage. In addition, cohabiting couples who live in a state where common law marriage is available are generally considered to be married if they have a child. Once established, common law marriages are no different from regular marriages, including acceptance of the common law marriage by all other states and government institutions dealing with tax collection and the redistribution of income, and the need for a legal divorce to dissolve the union and distribute the assets. Thus governments provide the same protections to those in a common law marriage as to those in a regular marriage.

Because the US does not collect statistics on the type of marriage (whether common law or regular), estimates of the effects of common law marriage are based on comparisons of outcomes in states where common law marriages are available with those where they are not and, in states that have repealed common law marriage laws, on comparisons of outcomes before and after the repeal.

Common law marriage and couple formation

An analysis of a large representative sample of US residents aged 18–35 covering all states over 1995–2011, including the three states that repealed common law marriage laws during this period, found that the availability of common law marriage reduces the probability of cohabitation and marriage among both men and women [6]. The three states that repealed the laws experienced more couple formation right before and right after the repeal. However, overall couple formation rates declined in the US during this period, so repeal of common law marriage by these states likely had only a small effect on total couple formation in the US.

The effects of common law marriage availability on couple formation were evident only in states where there are fewer men than women (low sex ratio), were larger for men than for women and differed by education level. The availability of common law marriage has negative effects on the likelihood of marriage and cohabitation for both men and women where sex ratios are low. When sex ratios are high, no effects are found [6]. Effects of common law marriage availability on couple formation are more likely for childless individuals than for those with children. The availability of common law marriage affects marriage and cohabitation more among men with a college education than among men without one and more among women without a college education than among women who graduated from college. The repeal of common law marriage by three states since 1996 thus contributed to increased marriage rates among educated men and reduced marriage rates among women with low education. To the extent that the repeal affected men more than women, it could have contributed to the fact that marriage has become relatively more common among educated Americans than among those lacking a college education.

Common law marriage and labor supply and time spent in household production work

Using a similar sample of US residents aged 18–35 over the period 1994–2011, another study examined the association between common law marriage availability and labor supply [1]. It found a negative correlation between common law marriage availability and the labor supply of white married women, college-educated married women, and married women with children. Overall, for married women, common law marriage availability reduces work time by one to two hours a week. The only finding for men was a positive effect of the availability of common law marriage on the labor supply of married men. No effects were found for single or cohabiting respondents, whether male or female. Thus, even though these effects on labor supply were small, the repeal of common law marriage laws since 1996 may have contributed to gender convergence in labor supply.

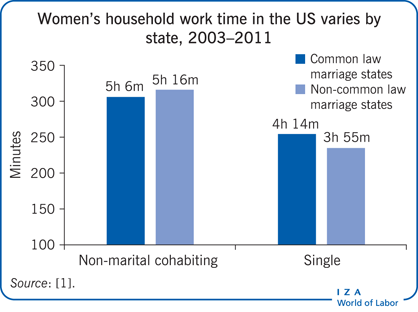

An analysis of time use survey data for 2003–2011 for women aged 18–35 suggests that many married and cohabiting women spent more time in household production and leisure before the abolition of common law marriage.

Common law marriage and teenage childbearing

Using data on US women aged 15–25, another study examined the association between the availability of common law marriage and childbearing over the period 1990–2010 [4]. During this period, four states repealed laws recognizing common law marriage (Ohio, Idaho, Georgia, and Pennsylvania). In the states where common law marriage was available but then repealed, the odds that teenage women aged 15–18 would become mothers for the first or a subsequent time increased, with a larger increase among young black teens than white teens. The negative association between the availability of common law marriage and being a young mother was strongest between one and four years before the repeal.

A small negative association was also found between common law marriage availability and childbearing by women aged 19–21. No clear association was found for women aged 22–25. To the extent that the availability of common law marriage leads to a reduction in teen birthrates, it is socially desirable.

Common law marriage and welfare dependency

The possible impact of common law marriage on reliance on government support has not yet been systematically examined. However, some have posited that a major reason that Utah reinstated common law marriage in 1987 was to establish legally that mothers in cohabiting couples are married and therefore not eligible for government support. Utah is the only state to have reinstated common law marriage after abolishing it. Research shows that the availability of common law marriage is most likely to discourage couple formation by women without a college education [6]. These women are also the most likely to be poor and dependent on government welfare services. Recognition of this effect of common law marriage may have led other states to avoid following Utah’s example.

Framing the results

To understand better why availability of common law marriage has the effects reported above, it helps to think of the law in the context of which member of a couple performs the household production, and what cost that entails for the other partner or spouse. When one spouse or partner does a larger share of the household production work than the other, that spouse or partner is often compensated for that extra household work, in part in the form of financial protection in case of separation or death. Marriage and divorce laws influence the benefits that such household producers may be getting in return for engaging in domestic activities, as can be examined through analysis of the demand for and supply of a spouse’s work in household production [7]. Bargaining theories of marriage might offer similar insights by possibly accounting for the effects of laws on the bargaining position of individuals forming couples [8], [9].

In couples cohabiting without marriage, the couple’s principal household producer is less likely to be offered financial protection by the other partner than is the case in married couples, or the protection may be less comprehensive. In states with common law marriage, the distinction between marriage and non-marital cohabitation is more ambiguous than it is in other states: where common law marriage is available, cohabiting domestic producers can obtain the same benefits that are available to their married counterparts.

Today in the US and in all countries for which time-use data are available, women perform most of the household production work undertaken in couples, such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Women were doing an even larger share of domestic production in couples observed in 1990, the earliest year examined by recent studies of common law marriage. It follows that the principal potential beneficiaries of common law marriage are women who are the principal domestic producers in their couple. The law can be interpreted as forcing men to offer cohabiting female household producers the protection of marriage and divorce laws, making women’s domestic production more costly to them.

Where common law marriage applies, men will thus perceive the household production supplied by a female unmarried partner as being potentially more costly, and they are likely to react to the higher cost by being less willing to agree to an implicit contract involving the exchange of their money (possibly in the future in case of separation or death) for domestic production supplied by a female cohabiting partner. Thus, men will avoid couple formation. Demand for domestic production by actual or potential married men willing to compensate women who may perform domestic work in marriage declines the higher the production cost. This is similar to the effect of a minimum wage in a labor market: when employers have to pay higher wages, they may respond by hiring fewer workers.

Relative to uneducated men, better educated men are more likely to avoid couple formation when common law marriage is available because they stand to lose more from a marriage that may be thrust on them unilaterally. In contrast, women with less education are more likely than better educated women to become part of a couple when common law marriage is available: the protection that such law offers to cohabiting women with low education will motivate some women to become part of a couple.

This conceptual framework also helps explain why teenage women are expected to have fewer children in jurisdictions where common law marriage is an option. The option of offering a woman a homemaking or childbearing “job” while in an unmarried couple appears more costly to men who wish to avoid having a child with a teenager, who may claim rights under common law marriage once she is older. Women aged 15–18 are considered minors and are more likely to be excluded from couple formation and motherhood by the requirements of common law marriage than are more mature women aged 19 and older to whom the option of a regular marriage is more available.

The same conceptual framework also helps explain why common law marriage is associated with lower labor supply by women who adhere to traditional views about gender roles. Women who engage in household production and who receive the “benefits” implied by common law marriage will feel less need to enter the labor force to protect themselves financially in case of separation or death. The availability of common law marriage raises the “price” of the household production work of married women in traditional gender role couples and therefore also raises the wage needed to induce them to take a job in the wage labor market (the reservation wage), leading to lower female labor supply.

The effects of the availability of common law marriage on labor force participation have been shown to be larger for college-educated married women and for white women than for women without a college education and for black women. This makes sense in terms of the framework proposed here. Marriage markets are likely to establish higher compensation for college-educated women who supply household production work than for their counterparts with less education and for white women performing household production work than for black women [7]. Therefore, the availability of common law marriage affects better educated women’s labor supply more than that of their less educated counterparts and white women’s labor supply more than black women’s.

However, to the extent that the availability of common law marriage leads to higher financial obligations for men in couples that adhere to traditional gender roles, these men will need to work harder in the labor force to pay for their higher financial obligations. This trade-off explains why married men are more likely to work in the labor force when common law marriage is available than when it is not.

Comparing choice of marriage type in the US and France

As explained, because US marriage statistics do not distinguish whether individuals are in a regular marriage or a common law marriage, studies on the effects of common law marriage are based on comparing outcomes in jurisdictions where common law marriage is available with the same outcomes where it is not available. France, which offers couples a choice between traditional marriage or, since 1999, civil union, does collect data distinguishing between the two forms explicitly. In addition, couples in France may select between two legal regimes for property allocation: common (community) property (the default for regular marriages) and separation of assets (the default for civil unions since 2007). Because French surveys collect data on both marriage type and legal regime, the French studies are based on individual data on the type of marriage, unlike US studies.

The findings on the effects of common law marriage availability in the US have parallels in studies of the choice of marriage type in France. At least four parallel findings are consistent with the conceptual framework based on marriage market analysis used to study the effects of the availability of common law marriage in the US.

First, in the US, studies suggest that where common law marriage is available there is less couple formation. In France, the introduction of civil union as an option led to more couple formation. These results are compatible because civil union makes marriage less costly: there are fewer future obligations associated with civil union than with regular marriage, and couples entering into civil union need not worry about possible unilateral marriage down the road. Common law marriage has neither a start date (it is often claimed a considerable time after cohabitation has begun) nor defined rules (one partner may consider the union to be a marriage while the other does not). In contrast, regular marriage in both countries and civil union in France have clear start days and terms that are well understood by both partners. As a result, couple formation is costlier where common law marriage is available. In both the US and France, the costlier it is to form couples, the less couple formation there will be.

Second, findings for the US show that where common law marriage is available, better educated men are more likely to avoid couple formation than less educated men. The better educated are also likely to be wealthier. For married couples following traditional gender roles, with the female spouse doing more of the household production work and earning less in wage employment, divorce laws imply that the wealthier, male spouse will be required to make payments to the female spouse in the event of a divorce. For that reason, more educated and therefore wealthier individuals stand to lose more from being in a couple in jurisdictions where common law marriage is available than in jurisdictions where it is not, and US findings confirm that. The parallel finding based on French data is that individuals with more assets more frequently chose legal marriage regimes that call for separation of assets rather than community property. The same study also found that more people with assets who were entering marriage opted for separation of assets in 2010 than in 1992. In the interim period between 1992 and 2010, France passed the civil union law and then a law declaring separation of assets to be the default regime for civil unions. Faced with these options, a greater number of wealthier French people may have chosen civil union rather than marriage. In addition, fewer of those who chose marriage might have opted to marry under a community property regime once the separation of assets option became available since it is less costly to a spouse with assets in case of divorce. In both the US and France, the options that imply a higher cost of couple formation have a stronger negative impact on couple formation by individuals who own more assets.

Third, US studies find that when common law marriage is available, married women are less likely to participate in wage labor. In France, which offers a choice of marriage or civil union and community property or separation of assets, two studies have documented that women in separate asset marriages are more likely to engage in wage labor than their counterparts in community property marriages [10]. To the extent that couples follow traditional gender roles and women do the bulk of household work, the more women expect to get paid if the marriage dissolves, the more they will engage in household production and the less they will engage in wage labor. In the US, women who adhere to such traditional gender roles are likely to achieve a better financial outcome when they are married in jurisdictions where common law marriage is available than in jurisdictions where it is not. In France, women in traditional gender roles may perceive that a regime of separation of assets offers them a lower “wage” for their work in household production than they would obtain under a community property regime. In both cases, the lower the “wage” for household production in marriage, the more women are likely to participate in the labor force.

Fourth, studies for the US find a positive effect of common law marriage availability on childbearing among young teenage women but not among women beyond their teen years. There are at least two possible forces at work here. On the one hand, the availability of common law marriage encourages women in couples who potentially benefit from the possibility of unilaterally declaring marriage to engage in more household production and to have more children. On the other hand, men may be discouraged from cohabiting by the higher cost of household production supplied by the (potential) mothers of their children that is implicit in common law marriage, thus lowering fertility. In France, there was an increase in childbearing following the introduction of civil unions in 1999, which had the effect of making household production by women less costly to men in couples following traditional gender roles, and the increase was greater in regions where civil union was adopted at higher rates [11]. These findings suggest that the more costly household production work by mothers under the pre-civil union status quo discouraged childbearing. It thus seems that in both countries, perhaps counterintuitively, when the government offers less generous protection to women engaged in household production under a traditional gender role model, men respond by being more willing to form heterosexual couples conducive to childbearing.

Limitations and gaps

A major limitation in studying the effect of common law marriage in the US is the inability to determine whether couples who are married in common law marriage states were joined in regular marriage or in common law marriage. All the studies of common law marriage, therefore, can only examine the effects of the availability of common law marriage rather than the direct effects of common law marriage itself. That is one reason why studies for France, which also offers some choices regarding couple formation and collects data on the type of union, were used to bolster the findings of US studies. It would also be interesting to study more cases, drawing on the experience of other countries, and to generalize the findings reported here. The lack of availability of the necessary data prevents this from being done. To further advance the study of common law marriage in the US, surveys will need to collect information from respondents on the type of marriage they have entered into.

The studies summarized in this paper assume that the repeal of common law marriage in some states was an exogenous change. However, it is certainly possible that factors that led to increases in couple formation may also have pushed states to repeal common law marriage [5]. One of these factors may be social norms that are increasingly tolerant of cohabitation and accepting of an egalitarian division of labor within the household. The more egalitarian a society’s gender norms, the more cohabitation is likely to occur. Common law marriage goes against that trend: by providing marriage-like protection to cohabitants who perform most of the household production (typically women), the availability of common law marriage discourages men from cohabiting.

Summary and policy advice

In both the US and France, legislation in recent decades has moved toward reducing the cost of couple formation to the parties involved. One way this has been accomplished in the US has been by abolishing common law marriage. France introduced a new form of couple formation, the civil union. In both cases, these changes lowered the cost of cohabitation more for wealthier individuals than for less wealthy ones. The evidence for policies encouraging an end to common law marriage is ambiguous. Common law marriage availability appears to discourage teen fertility and encourage men’s labor supply. These are desirable outcomes. However, the availability of common law marriage discourages two other also desirable outcomes: women’s labor supply and couple formation. In addition, these impacts on the labor supply—and thus on the wealth of individuals who form couples—and on childbearing decisions influence inequality across households, another concern of policymakers.

In deciding whether to abolish or possibly to reinstate common law marriage, policymakers need to decide which of these outcomes are more important. So far, only one state, Utah, has reinstated common law marriage, and it did so long ago, in 1987.

The findings from the studies reported here suggest that governments can consider making additional options available when regulating and organizing the legal process of couple formation and dissolution, based on the model used in France. Individuals who want to form legal couples could be given a choice between marriage and other types of union, such as civil union, that involve fewer obligations on the part of the partners and the government. In addition, those who are getting married could be allowed to choose between legal regimes for distributing assets in case of divorce, whether community property or separation of assets.

Overall, laws regulating marriage and cohabitation can have more unintended consequences than is usually recognized. Thus, it is important that policymakers become more aware of the (often implicit) costs of couple formation and of laws such as those recognizing common law marriage in the US and Brazil. These costs influence outcomes related to couple formation as well as to the distribution or responsibilities and benefits between members of a couple.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. She also thanks Anne Laferrere for comments. Previous work of the author together with Victoria Vernon contains a large number of background references for the material presented here and has been used extensively in all major parts of this article [1], [5], [6].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Shoshana Grossbard

Marriage laws in France contrasted with those in the US

Source: Rault, W., and E. Bailly. “Are heterosexual couples in civil partnerships different from married couples?” Population & Societies 497 (2013): 1–4.