Elevator pitch

Around ten countries currently use a variant of a national income-contingent loans (ICL) scheme for higher education tuition. Increased international interest in ICL validates an examination of its costs and benefits relative to the traditional financing system, time-based repayment loans (TBRLs). TBRLs exhibit poor economic characteristics for borrowers: namely high repayment burdens (loan repayments as a proportion of income) for the disadvantaged and default. The latter both damages credit reputations and can be associated with high taxpayer subsidies through continuing unpaid debts. ICLs avoid these problems as repayment burdens are capped by design, eliminating default.

Key findings

Pros

ICLs deliver consumption smoothing by reducing or eliminating student loan repayment burdens on disposable income when debtors’ future incomes are low.

By coupling loan repayment amounts to a debtor’s actual income, ICLs provide insurance against default.

ICL debt can be collected efficiently if functional tax and personal identification systems are in place.

Cons

TBRLs have the strong potential to create major repayment difficulties for borrowers.

TBRLs do not provide debt default insurance for borrowers.

TBRLs can lead to credit reputation loss for the borrower due to default.

Systems based on TBRLs create inequality in educational access due to a high fear of future debt default by low-income prospective students.

ICLs have sophisticated administration requirements that may be unachievable for some countries.

Author's main message

ICLs possess considerable benefits (when compared to TBRLs), providing insurance to borrowers against both future loan repayment hardships and default. In contradistinction, TBRLs can be very costly to some borrowers who experience periods of low future income. In general, the public sector administration costs of an ICL scheme are very small for countries that have a comprehensive income tax or social security payment administration in place. This, in combination with the additional borrowers’ insurance benefits, suggests strongly that ICL policies are preferable to the standard TBRL model. This appears to be particularly true in weak graduate labor markets, such as those experienced during the economic stagnation associated with Covid-19.

Motivation

In 1989 a higher education financing policy initiative took place in Australia that can be seen as a first step toward major international reforms regarding student loans. The policy, then known as the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS), involved domestic students being charged tuition, but with the obligation to pay being deferred until debtors’ income rose above a given annual threshold, with repayments set at a maximum of between 1% and 10% of annual personal income. A critical and efficient aspect of this reform was that the repayments would be collected by employers and remitted to Australia's internal revenue service, the Australian Tax Office, in much the same way that personal income taxes are.

Over 30 years later, HECS (now known as HECS-HELP), which can be accurately categorized as an income-contingent loan (ICL), exists in different forms in around ten other countries, although scheme design, eligibility, interest rates, and debt forgiveness regimes differ widely between systems, and have changed over time within jurisdictions. In the systems operating the best, the essential characteristics of the loans—income-contingency and collection through auspices equivalent to each country's internal revenue service—are shared.

Evidence suggests that the economic, administrative, and equity cases for ICLs are very strong, although there are caveats with respect to both design and operation. Relevant in this context is the need for government intervention in higher education financing in the form of loans; the limitations regarding repayment burdens that are associated with time-based repayment loans (TBRLs), which have been the most common form of intervention; and the advantages of, and challenges associated with, ICLs.

The potential benefits of ICLs for both the student debtor and for governments that guarantee student debt are significant. An examination of these benefits, as well as a look at the most common current form of student loan debt, TBRLs, is therefore important. Of great contemporary interest is that pertinent comparisons of student loans in the time of Covid-19 can be presented.

Discussion of pros and cons

History and worldwide coverage

ICLs typically take a form that is similar to the scheme initiated in Australia. Debts to cover tuition costs (and in some cases income support, such as in New Zealand and the UK) are recorded while a person is studying, and the income tax authority is informed of an individual's future repayment obligation. When the debtor, most often as a graduate, is receiving an income that is above the given threshold, that person's employer takes a percentage of his/her income per period and remits it to the tax (or loan) authority. For example, the first repayment threshold in Australia in 2022 is about AU$47,000 per year and at that point the debtor repays 1% of annual income, or around AU$500. A typical tuition debt in Australia is about 45–50% of the recurrent cost of higher education, although in other countries the obligation can be quite different. For example, in England student debtors face close to 100% of recurrent costs, although most students do not repay their loans in full and the government loan subsidy is around 45% [1].

Several countries other than Australia have adopted universal ICL, meaning that all persons enrolling in higher education are covered. These, and the year of the adoption, are: New Zealand, 1991; the UK, 1998; and Hungary, 2001. In other countries there has been partial adoption of ICL variants: the US, 1994; Thailand, 2006; South Korea, 2009; Brazil, 2016; the Netherlands, 2016; Japan, 2017; Canada, 2017; and Colombia from 2023. Governments of some of the second set of countries, as well as some others, are in the process of considering research and/or policy development underpinned by the benefits of a universal ICL; these include: Brazil, Chile, France, Malaysia, and Ireland.

Why are student loans necessary?

A significant financing reality for higher education in most countries is that there is a contribution from students and a taxpayer subsidy [2], [3], [4]. Agreement on the appropriateness of this so-called “cost sharing” comes from two related features of higher education: high private rates of return and the existence of externalities; in combination, these justify part-payments from both parties. An important additional question to pose is: is there a role for government beyond the provision of the subsidy?

The issue is more clearly understood by considering what would happen if there were no higher education financing assistance involving the public sector. In other words, a government, convinced that there should be a subsidy, could simply provide higher education institutions with the appropriate financial level of taxpayer support, and then allow market mechanisms to take their course. Presumably, without any other steps, this would be accompanied by institutions charging students for the service.

However, major problems exist with this arrangement, traceable to the potent presence of risk and uncertainty. An essential point is that educational investments are risky, with the main areas of uncertainty being as follows [2], [4], [5], [6]:

Enrolling students do not fully know their capacities for (and perhaps even true interest in) the higher education discipline of their choice. This means, in the extreme, that they cannot be sure they will graduate; in Australia, for example, around 25% of students end up without a qualification and in countries like Colombia, drop-out rates are considerably higher.

Even given that university completion is expected, students will not be aware of their likely relative success in their area of study. This depends not just on their own abilities, but also on the skills of others competing for jobs in the area.

There is uncertainty concerning the future value of the investment, particularly regarding future labor market conditions. What looked like a good investment at its start might turn out to be a poor choice when the process is finished.

Many prospective students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, may not have sufficient access to information concerning graduate incomes, due in part to a lack of contact with graduates.

These uncertainties are associated with important risks for both borrowers and lenders. The key point is that if students’ future incomes turn out to be lower than expected, then the individual is unable to re-finance a different educational path. For a prospective lender, such as a bank, this problem is compounded by the reality that in the event of a student borrower defaulting on the loan obligation, there is no available collateral to recoup the unpaid balance, a fact traceable in part to the illegality of slavery. It is not possible for a third party to own and sell human capital and even if it was, its future value might turn out to be quite low, considering the above-noted uncertainties associated with higher education investments.

It follows that the market, on its own, will not deliver propitious higher education outcomes. Prospective students that are considered relatively risky, and/or those without loan repayment guarantors, would not be able to access the financial resources required for both the payment of tuition and to cover income support. This is inequitable, and also implies efficiency losses from the underutilization of the potential stock of human capital.

A critical point for policy from the above is that without some form of intervention, higher education financing will not deliver the most propitious outcomes in aggregate, nor can such markets deliver equality of educational opportunity, because those without collateral—the poor—will be unable to participate.

Consequently, nearly all governments intervene in the financing of higher education by making student loans available. There are currently two major forms that this loan intervention takes: TBRL and ICL. Conceptually, there are several varieties of the latter (such as income sharing arrangements) but the only type currently in existence from the public sector is known as a “risk-sharing ICL,” in which governments essentially pay the debts for former students whose lifetime incomes turn out to be insufficient to repay their debt. The following section examines some critical empirical findings with respect to both forms of assistance.

Time-based repayment loans (TBRLs)

Many countries, such as the US and Canada, use a specific financing scheme that potentially solves the capital market issue described above. Higher education institutions charge up-front fees, but students who qualify based on family incomes also receive TBRLs to help cover tuition and to provide income support. Public sector support usually takes two forms: the payment of interest on the debt before a student graduates, and the guarantee of repayment of the debt in the event of default. Arrangements such as these are designed to facilitate the involvement of commercial lenders, and the fact that they are a common form of financial assistance on an international scale would seem to validate their use. It is important to note that banks do not necessarily need to be involved since governments could provide the initial financing but still seek to collect on the basis of time (this is now predominantly the case in the US and Thailand, for example).

TBRLs address the capital market failure problem for lenders, since with the government guarantee there is then no need for collateral, meaning that the public sector assumes the lender risks and costs of default. However, solving this aspect of the provision of finance is not the end of the story.

Two problems persist for borrowers (students) under a TBRL scheme. Specifically, loans requiring repayment on the basis of time (a constant amount per month for example), rather than capacity to pay, are associated with the prospect of future financial hardships and default risk, both traceable to borrowers experiencing repayment difficulties as a result of (unanticipated) poor future financial circumstances.

Default risks and repayment hardships

By definition, all TBRLs have repayment obligations that are fixed with respect to time (e.g. the typical arrangement with respect to Stafford loans in the US is a ten-year repayment period) and are thus collection insensitive with respect to an individual's future financial circumstances. This raises the prospect of default for some borrowers, which would in turn damage a student's credit reputation and thus eligibility for other loans, such as a home mortgage [2], [4]. Thus, in anticipation of potential damage to their credit reputation, some prospective students may prefer not to take the default risk of borrowing because of the high potential costs. This behavior is a form of “loss aversion,” and has been described in relevant research [7].

Strong evidence based on the National Post-secondary Student Aid Study for the US shows that experiencing low earnings after leaving formal education is a strong determinant of default [8]. Importantly, borrowers from low-income households, and minorities, were more likely to default, as were those who did not complete their studies. This supports the notion that some poor prospective students might be averse to TBRLs due to the risks of repayment hardships and default.

Thus, arguably the most significant problem for students with TBRLs concerns possible consumption difficulties associated with fixed repayments. If the expected path of future incomes is variable, then a fixed level of debt repayment increases the variance of disposable income (i.e. income available after debt repayment), with the essential issue coming down to what are known as “repayment burdens” (RBs), the proportions of graduate incomes per period that need to be allocated to repay student loans. The simple RB identity is given by the ratio of the repayment amount of the loan in a specific period for a debtor and his/her personal gross income in that period. This ratio represents the percentage reduction in a debtor's own income after per period repayments of their student debt and has been an empirical norm in understanding the potential impact of TBRLs on debtors’ financial well-being.

RBs are the critical issue associated with TBRLs, reflecting that as the proportion of a graduate's income allocated to the repayment of a loan increases, the remaining income available for consumption decreases. Lower student debtor disposable incomes are associated with the two student loan issues discussed previously: repayment hardship and higher default probabilities. This point is critical in the policy choice context, because the essential difference between TBRLs and ICLs is that the latter have RBs set at a maximum, by law; in contrast, RBs for TBRLs are unique for each individual borrower, and can in theory be close to zero for very high-income debtors while being well over 100% for very low-income debtors.

A considerable body of empirical analysis exists regarding RBs associated with TBRLs [9]. An innovative aspect of this empirical work is that the calculation or simulation of RBs for graduates is done at different parts of the graduate earnings distribution. This allows the impact of student loan repayment obligations to be revealed for the whole of the graduate income distribution according to age and sex, a major improvement over previous analyses that focused on RBs at the means of graduate income distributions.

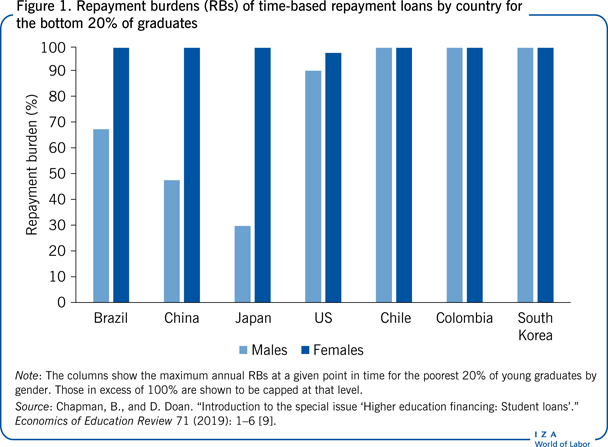

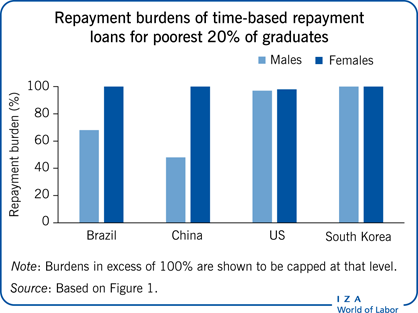

The main results for graduates in the bottom 20% of the income distribution in seven countries with TBRLs where this analysis takes place are illustrated in Figure 1 using different cross-sectional data sets from the last ten years. The results illustrate the maximum repayment burden for debtors by country for any point of time during loan repayment, rather than the average, because loan repayment hardships matter at the time they occur.

Figure 1 shows: (i) Despite TBRLs differing widely between countries in terms of loan size, repayment periods, and interest rates, the research consistently illustrates that RBs are, arguably excessively high, for graduates at the bottom of the earnings distribution across quite different national environments; and (ii) RBs can be extremely high under TBRL schemes. The maximum RBs for the defined low-income male graduates range from about 30% in Japan to 98% in the US; and for females they range from 98% in the US to in excess of 100% in Brazil, China, Japan, Chile, South Korea, and Colombia.

Although not shown in Figure 1, in all cases—except for Japanese women—RBs are highest in the first year after graduation when graduate earnings are at the lowest. (The Japanese experience of very high RBs for females aged in their early 30s is a result of the marked decline in female labor force participation rates after marriage.)

These estimates reveal that mortgage-type student loan schemes are associated with very high RBs for low-income young graduates, particularly in the first years of repayment, and are thus likely related to significant problems of consumption hardship, and a concomitant high minority of prospective students facing defaults. When income dynamics are also factored in, the excessive RB problem impacts on a much larger group of students than when just one year of data is focused on [10].

Income-contingent loans (ICLs)

The essential benefit of ICLs, if properly designed, is that the arrangement avoids the problems outlined above with respect to TBRLs. Critically, RBs are not an issue with ICLs by design because maximum RBs are set by law. Further, for many countries, administrative costs for the collection of ICLs are very small.

Consumption smoothing

The essential difference between TBRLs and ICLs is that ICLs are collected when and only if debtors have the financial capacity to repay, which serves to protect former students who consistently earn low incomes. Thus, unlike TBRLs, ICL schemes offer a form of “default insurance,” since debtors do not have to pay any charge unless their income exceeds a pre-determined level. After the first income threshold is exceeded, ICL repayments are capped at a fixed and low proportion of the debtor's annual income. For example, in Australia, New Zealand, and England/Wales, the maximum repayment proportions of annual income for ICLs are 10%, 12%, and 9%, respectively [4].

Effectively, the low maximum RBs with ICLs deliver consumption smoothing since there are no repayment obligations when incomes are low. As graduates’ incomes rise, so does their proportion of income being remitted to repay debt. The removal of repayment hardships and the related advantage of default protection via income-contingent repayment resolves the fundamental problems for prospective borrowers inherent in the traditional approach to student loans.

A significant further point is that the protections of an ICL could particularly matter in times of recession for both borrowers and governments. That is, if there are poor short-term employment prospects at the time of graduation, such as was the case for many countries from 2008 to 2013, borrowers will suffer from high default rates and governments from low loan repayments in systems with TBRLs. The issue is avoided with an ICL and is taken up further below with respect to the implications of different student loan forms in the time of Covid-19.

Transactional efficiencies

ICLs can be collected very inexpensively, a feature labelled “transactional efficiency” [7]. The Australian Tax Office estimates the collection costs for the government related to ICLs at less than 1% of yearly receipts. The Australian system seems to have worked well regarding collections, and there are clearly significant transactional efficiencies in the use of employer withholding for the collection of an ICL in the context of the income tax system. Estimates of the costs of collection for England's and Wales’ ICLs are very similar [11].

This efficiency is achieved because the collection mechanism simply builds on an existing and comprehensive personal income tax system, and is essentially a legal public sector monopoly. It should be acknowledged that, as with all government subsidized loan schemes, a system is required that minimizes the potential for non-repayment from debtors going overseas. One (likely very ineffective) approach would be to involve the cooperation of other governments in the collection of debt. However, as first instituted in New Zealand with a similar approach now adopted in Australia, an alternate system could be designed that puts a legal obligation on a debtor going overseas to repay amounts of their obligation reflecting incomes in each year in which they are away.

Some empirical observations on access to education

When HECS was first implemented in Australia important concerns were raised regarding the new tuition arrangement's potential to exclude prospective students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Significant research has investigated HECS's impact on educational access for economically disadvantaged people, and the main conclusions from the Australian case are as follows: (i) The relatively disadvantaged in Australia were less likely to attend university even when there were no student fees; (ii) The introduction of HECS has been associated with overall increases in higher education enrolments; and (iii) HECS has been associated with increased participation by prospective students from relatively poor families (although the increase was slightly more pronounced for less disadvantaged students, especially those in the middle of the wealth distribution).

In England, analysis suggests that the introduction of ICL tuition charges, coupled with ICLs for living costs, has resulted in a large increase in student numbers (because government costs per student have been reduced) with the biggest increase in participation for those from the poorest backgrounds who saw a big increase in upfront support for attending university [12], [13].

Covid-19 and the design of student loans: The importance of ICL insurance

There is an additional issue related to comparisons of the costs and benefits of different approaches to student loans which would not have been realized in such a major way without the contemporary economic trauma experienced in 2020 and beyond as a result of Covid-19. This is that while ICLs are motivated in part to protect student borrowers from the adverse demands that are a feature of individual experience, they also provide broad levels of insurance for entire cohorts of borrowers entering a labor market in a period of aggregate economic trauma, such as that associated with Covid-19.

The basic point is that graduates who finished university in the early 2020s faced a relatively hostile labor market with fewer job opportunities, and this is going to put particular strain on those with TBRLs. Consequently, the debt repayment obligations in this period were much harder to meet, and significantly more difficult than could ever have been expected pre-Covid-19.

Moreover, experience from previous recessions indicates that when the graduate labor market is poor, graduates will be less likely to find work and will start off in lower paying occupations than they might have expected. Given the likely scale of the downturn into which students have been graduating in 2020 and beyond, it is likely to take at least five, and perhaps ten, years for these effects on their earnings to wear off.

With respect to this issue, data from the UK labor force survey have been analyzed recently to illustrate the likely effect of a major recession on graduate labor market experience [14]. The clear message from this research is that the adverse consequences of a significant labor market downturn continue for a long time, meaning that graduates entering the labor market now or in the near future will be casualties of Covid-19 for the foreseeable future, perhaps as long as five or more years.

The student loan issue in this respect is that if new graduates are TBRL debtors they will face significant loan repayment stresses and higher than anticipated default probabilities. In contrast, graduates with ICL debts are protected against such adverse exigencies because no repayments are required if they are unemployed or earning low incomes.

ICLs as higher education policy: A significant caveat and the role of design

The introduction of an ICL scheme has turned out to be a relatively simple matter from an administrative point of view. The reasons are that the public sectors of the adopting countries feature a strong legal framework, a universal and transparent regime of income taxation and/or social security collection, and an efficient repayment mechanism. The last involves computerized record keeping of residents’ vital financial particulars, a universal system of unique identifiers, and, most critically, the existence of employer withholding from personal incomes.

Under these circumstances, it is not complicated to identify and track individual citizens and their incomes over time and space; moreover, it is not expensive to tack an additional function onto the existing employer withholding tax collection mechanism: the collection of payments from ex-students, on the basis of a proportion of income. In the developing world, however, these preconditions to an ICL scheme are often lacking and compromises might need to be found. A related issue is that even if administrative mechanisms appear to be in place, it is important that the system provides up-to-date knowledge of incomes, since lags could mean inappropriate deductions [15].

An acknowledged difficulty in the administration of an ICL compared to a TBRL is that, with the former, there must be an efficient way of accurately determining, over time, the actual incomes of former students. Furthermore, it seems clear that a basic requirement for the introduction of an ICL is a strong legal framework and functional judicial system. Indeed, it is hard, from a developed-world perspective, to imagine implementing a workable scheme outside this context; even so, these administrative pre-conditions are generally available.

A final set of points addresses design issues. ICLs around the world differ with respect to some key collection parameters and other policy features, implying that there is no single ideal system. The following examples illustrate some of these differences. Approaches to interest rates vary widely the Hungarian system provides no interest rate subsidies, while the New Zealand arrangement has a nominal interest rate of zero, implying very high subsidies. Furthermore, the first income levels and repayment conditions vary significantly, with most basing debt collection on a marginal rate involving additional income, as compared to the Australian system, which collects a percentage of total income. Consequently, the amount of unpaid debt in countries such as England and Wales will be considerably higher than in Australia; although in the latter there is evidence of income bunching at the first threshold of repayment when the first repayment rates of collection were 4% of income in the past, implying the potential for behaviors from moral hazard in the past. With the first rate of repayment from income now restored in Australia to 1% the issue is resolved.

These administration and design issues are very important to the potential success of an ICL system, at least in terms of public sector subsidies. Nevertheless, the key point remains: if designed properly, ICLs are a superior student loan system to the more conventional TBRLs, essentially because the former offer insurance against hardship and default. It should thus be no surprise that the international transformation within higher education financing has taken clear steps toward the ICL model over the last 30 years.

Limitations and gaps

Several important issues remain from this comparative analysis of ICLs and TBRLs. For starters, there has been an insufficient examination of the default costs associated with TBRLs for individuals. A critical point here is that people defaulting on student loans also end up damaging their overall credit reputations, which results in them having difficulty and higher costs when attempting to secure non-student loans. There is similarly a lack of information related to the public sector costs associated with TBRLs. These costs are incurred by governments since all unpaid debts are financed from taxpayer receipts. Furthermore, insufficient empirical documentation has been collected regarding the value of consumption smoothing for debtors with ICLs. Finally, the potential inability of public sector administrative structures to provide for the efficient collection of ICLs in some developing countries remains a policy implementation issue.

Summary and policy advice

Over the last 30 years there has been a strong move toward the adoption of ICLs to finance higher education. More than a handful of countries, and given policy debate and ongoing research findings, potentially a few more will soon, have followed Australia's lead in using employer withholding in the income tax or social security system to collect contingent debt. Essential reasons for the continuing transformation of student loans include the lack of insurance with TBRLs against both consumption hardship and default. While ICLs provide the type of insurance mechanism to allow equitable and transactionally efficient loan collections, there is a need in many developing countries’ institutional environments to focus on improvements in administrative capacities. When this occurs, there should be little doubt that ICL reforms are apposite worldwide.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank several anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. This article is based on joint research with many colleagues from around the world. Bruce Chapman wishes to acknowledge financial assistance from the Australian Research Council (LP1 102200496) and the College of Business and Economics at the Australian National University. Both authors would like to acknowledge gratefully financial assistance received from the ESRC-funded Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS and from the HEFCE- and ESRC-funded Centre for Global Higher Education at UCL—IOE and Oxford, Grant No. ES/M010082/1. All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Version 2 of the article includes a new figure, updates the research to discuss how a pandemic associated with economic stagnation can affect repayment, and significantly updates the reference lists.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Bruce Chapman and Lorraine Dearden