Elevator pitch

Some studies estimate that the value of time spent on unpaid caregiving is 2.7% of the GDP of the EU. Such a figure exceeds what EU countries spend on formal long-term care as a share of GDP (1.5%). Adult caregiving can exert significant harmful effects on the well-being of caregivers and can exacerbate the existing gender inequalities in employment. To overcome the detrimental cognitive costs of fulfilling the duty of care to older adults, focus should be placed on the development of support networks, providing caregiving subsidies, and enhancing labor market legislation that brings flexibility and level-up pay.

Key findings

Pros

Informal caregivers such as adult daughters or spouses may provide a better quality of care than formal care providers such as home help or nursing home care.

Flexible working hours may help caregivers balance care obligations and employment by providing them with a sufficient income and a social network through work.

Interventions to improve carers’ employment opportunities can provide a form of respite and self-esteem, and cash allowances can compensate caregivers for their reduced working hours and costs of providing care.

Evidence from recent long-term care reforms in Scotland and Spain suggests that caregiver support can have a significant impact on caregiver well-being and mental health.

Cons

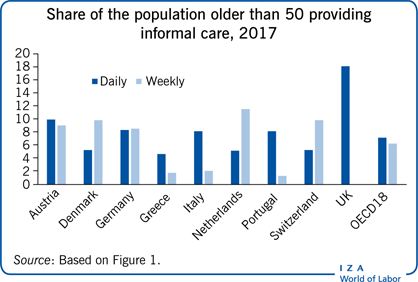

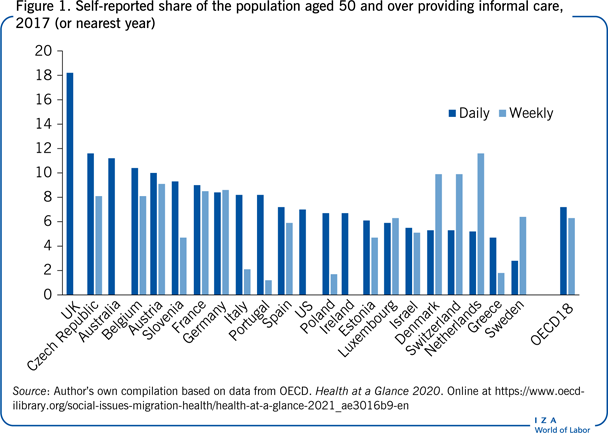

A significant share (13%) of people aged 50 and over report providing some adult informal care at least weekly in OECD countries.

Providing care reduces leisure, depresses work opportunities, and becomes a well-being burden to many individuals.

Most evidence suggests that caregiving has a relatively modest impact on labor force participation, although it can reduce the hours of work.

Care leaves are available to one-third of European employees; however, statutory leave for caregivers of older adults and flexible work arrangements are far less common than similar arrangements for child carers.

Author's main message

Caregiving can have knock-on effects on the time devoted to employment and leisure. It can exert detrimental effects on caregivers’ mental health and other dimensions of well-being, as well as society as a whole by increasing welfare claims. However, some policy interventions can partially compensate individuals for the cost of caregiving. Such interventions include the set-up of support systems in the form of home help, caregiving allowances, and caregiving leaves, as well as offering respite care and creating regulation that provides caregivers with further flexibility to combine the provision of care with employment.

Motivation

Caregiving arrangements for older adults are largely reliant on the provision of informal care by an adult child or spouse in most Western countries [1]. The typical traditional caregiver has been a “middle-aged daughter who adheres to some intergenerational social norm” [1], p. 6. Consistently, a growing body of research indicates that the presence of a daughter in the household is a strong predictor of both the availability of informal care and the type of caregiving arrangements a household relies on [1], [2]. However, such informal caregiving often refers to “care by default.” That is, carers are frequently steered to supply care “out of duty,” to fulfil a caregiving norm, rather than a preference evaluated on a pure individual-level utility. As a result, the supply of care has been shown to be a prominent source of caregiver stress [3], and depressive symptoms among caregivers are often directly related to the feeling of being “trapped in a particular role.” Moreover, such caregiving arrangements are not independent of the growing labor market participation among middle-aged women in most European countries. Higher employment opportunities for traditional caregivers increase the opportunity cost of caregiving, given that an increase in the time devoted to providing care encompasses a reduction in the time allocated to employment and leisure. Indeed, caregivers are not only impacted in terms of lost earnings but also in terms of weaker social networks. Work-related social networks can have an important influence on a caregiver's mental health and well-being. Hence, as these costs become more visible to individuals, an increased demand for formal care services such as home care or nursing home care can be expected, ultimately increasing long-term care spending [3], [4].

Discussion of pros and cons

Evidence

Across OECD countries, around 13% of people older than 50 report providing some form of informal care at least weekly (see Figure 1). The share is close to 20% in the Czech Republic, Austria, Belgium, the UK, France, and Germany. However, there is also significant variation in the intensity of the care provided. The lowest rates of daily care provision are found in countries such as Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, and the Netherlands, where a network of formal long-term care provision is comparatively more developed, and where public subsidies and support are more comprehensive than in other European countries [1]. In contrast, when examining weekly care provision, the nations exhibiting the lowest rates of provision are mostly Eastern and Southern European countries, including Poland, Estonia, Greece, Portugal, and Italy. Finally, when looking at the share of the population providing either daily or weekly care, the countries exhibiting the highest share of care provision include mostly central European countries such as Belgium, Austria, France, and Germany.

Private and social costs of adult caregiving

Caregiving is a costly activity, both for individuals (e.g. deteriorated mental health or lost earnings) as well as for society (e.g. caregivers do not devote their time to other potentially productive activities). Most caregiving duties are labor-intensive and time-consuming. Furthermore, given the emotional connection between informal caregivers (e.g. children or spouse) and care receivers, the provision of care tends to be mentally stressful, and at times even physically exhausting, which can have a negative impact on employment activities, and as a result on productivity, as well as caregivers’ well-being [3], [4]. In addition, changes in the supply of informal care can give rise to welfare claims, which deteriorate the social security balance sheet [5]. To date, the European Commission estimates that the annual value of time spent providing informal care in the EU27 is about 2.7 %, which exceeds the average spending on long-term care (LTC) as a share of GDP in the EU of 1.5% [5]. Indeed, whether estimated as the replacement cost of a professional caregiver, or the opportunity cost of employment, the economic value of informal care is considerably greater than the combined expenditures on nursing homes and paid home care [6]. Hence, a question that emerges is whether there is an efficiency and equity argument to expand support and subsidies for adult caregivers. Furthermore, how should such mechanisms be designed? Should policymakers concentrate on labor market regulations that reduce the time constraints to provide care? Or should the focus be on compensating stakeholders for the opportunity costs of care, including employee time and productivity losses?

Effects of care on employment

Caregivers of working age may be forced to forego employment to some degree. Given that most caregivers are female, this has the potential to impede further gains in women's employment rates. At the EU level, 65% of employed informal carers aged 18–64 work full-time, compared with 75% of all employed people [5]. Descriptively, the provision of care is also associated with higher rates of part-time work and slightly fewer hours worked. Caregivers are more likely than non-caregivers to exit the labor force or work at reduced hours and wages because of their caregiving obligations [7]. Particularly, women find it especially difficult to reconcile caring for an older adult with paid employment [8].

To date, although most evidence in the literature documents modest effects of caregiving on labor market participation [9], there are some effects that result from a less intense or unjoyful employment, especially among high-intensity caregivers. That is, the effects of caregiving differ depending on the intensity of care, or the time providing care. Indeed, cross-sectional analysis of the 1990 UK General Household Survey shows that when informal caregivers provide more than 20 hours of care per week they are not only less likely to participate in the labor market, but their hourly earnings are also lower than those of non-caregivers [8]. Hence, whether caregiving impacts employment participation or only reduces hours spent working depends on the number of hours of care provided. Furthermore, a 2018 study using panel data and instrumental variable analysis documents that providing informal care on a daily basis reduces the likelihood of being employed by 22% [10]. In contrast, providing care only “at least weekly” has no effect on employment. However, the authors find that informal caregivers are 5 percentage points less likely to work full-time.

Therefore, it can be concluded that intensive caregiving is associated with lower labor force participation among working-age caregivers. In Europe, evidence suggests that differences in the supply of care are the result of differences in local labor markets influencing the opportunity costs of supplying care. Consistently, employment shocks in Europe in the middle of the Great Recession in Europe (2007–2009) are found to exert an impact on informal care supply [11].

Effects on gender inequality

Women make up 61% of those providing daily informal care in OECD countries on average. Over 70% of informal caregivers in Greece and Portugal are women, but patterns of care vary by age group [5]. Younger carers (aged 50 to 65) are much more likely to be caring for a relative (e.g. spouse, parent, or parent-in-law) and may not be providing care daily. More specifically, caregivers over the age of 65 are more likely to be caring for a spouse. Caring for a spouse is more intensive, necessitating daily attention, and men and women are equally likely to take on this role. Intensive caregiving is linked to lower labor force participation among caregivers of working age, higher poverty rates, and a higher prevalence of mental health problems. Many OECD countries have implemented policies to assist family caregivers to mitigate these negative consequences [5].

Formal and informal care substitution

One of the constraints facing policymakers is that not all informal care can be substituted by formal care for several reasons. Only some types of care needs can be provided by low-skilled carers as they do not require major technical needs. However, often informal care still complements care by professionals. When informal care is complementary to formal care, a decreasing supply of informal carers would depress the probability of home care delivery, which could increase the demand for institutional care. Even when some care is subject to substitution, it is not clear whether individuals or government can afford it. Formal care allows informal caregivers some respite and reduces a more intensive use of care or allows for the transfer of an individual into a nursing home. That is, formal support plays a central role to reduce the care burden to a manageable level, allowing the employee to continue with the informal care arrangement reducing the time devoted to informal care.

Although not all forms of informal care are perfect substitutes for care that is provided by care professionals, formal care respite plays a central role in reducing the need for nursing home placement. Several empirical studies find evidence of such substitution effects, and suggest a clear negative correlation between informal and formal care alternatives in both the US and Europe [1]. With respect to severely impaired elderly parents, a 2009 study employing an instrumental variable strategy (using children's characteristics as instruments) and evidence from panel data, documents a negative correlation between the intensity of the care provision, in terms of the effect of a change in the hours of low-skilled formal care (e.g. housework, shopping, and minor care tasks) and the associated provision of informal care. In contrast, informal care is not found to be correlated with the weekly provision of high-skill care tasks (e.g. nursing care) [2]. However, evidence does suggest that nursing home placement can be avoided by some combination of informal care and formal home help.

Interventions to support caregivers

There are many types of interventions in use to provide support, either financial or otherwise, to caregivers. These include the cash subsidies, home care supports, employment leaves, respite care and flexible work schemes, tax incentives, and therapy and respite to caregivers.

Cash subsidies

Cash subsidies compensate caregivers for some of their time, and even at times, allow care receivers to purchase additional care in the market. The purpose of cash subsidies is to compensate caregivers for their reduced working hours or for the additional expenses incurred due to caring, with many caregivers experiencing personal financial strain. For example, a 2021 survey in the US reports that 78% of family caregivers have out-of-pocket costs averaging $7,242 a year [12]. However, the designs for such interventions are highly heterogeneous with caregivers typically being compensated based on their caregiving needs. In many European countries, the regulations for granting such compensation are extremely stringent to minimize disincentives to work among certain low-wage earners [6]. Subsidies can be both unconditional or conditional (on some specific care being provided to the care receiver). The latter might include a budget that specifies how the allowance should be spent to reduce moral hazard effects (e.g. incentives to spend the allowance on something else, or simply increase savings). Evidence from Spain indicates that a proportion of unconditional cash subsidies increased the precautionary savings of the care receiver's family. However, no such effects are found when families receive support in the form of home help [13].

It must be noted that cash subsidies are not without their downsides. Providing cash benefits directly to the care receiver, for instance, may encourage caregiver monetary dependency and thus decrease its intrinsic motivation. Likewise, if there is no specific provision to use benefits to pay for family caregivers, a cash subsidy or an allowance may instead be used to supplement the family's shared income, at the expense of the caregiver's individual status. Moreover, cash subsidies might have perverse incentives when they either serve to entrench traditional gender roles, or disincentivize the pursuit of formal employment.

To date, it is unclear whether government policy should primarily focus on designing cash subsidies, care supports, or both, under specific circumstances. Subsidies increase care receivers’ choice and flexibility and are argued to result in a higher quality of care. However, there are more opportunities to misuse resources with cash subsidies than with direct care support.

Several countries have made allowances contingent on care budgets or receipts justifying allowance use, known as “cash for care” schemes. This is true in the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Germany, and Austria, among other countries. Cash for care schemes are also seen as attempts to allow users who would otherwise lack resources to both choose and control the services they require, which is expected to increase their quality of care. Care recipients can use their care budgets to hire market-based care and domestic help, as well as their own family members or relatives (hence formalizing their duties). In general, these schemes entail a transfer of resources to caregivers but under the control of care receivers, to address specific needs that have been pre-defined and take the form of an allowance. They are usually justified by their consideration of the users’ preferences and needs, which can be heterogeneous. However, so far, evidence from Germany suggests that care budgets increase the amount of time allocated to care, but without a significant impact on final health outcomes.

Home care supports

Home care supports refer to services in the form of home help or daily care which can be publicly funded up to a certain number of hours per week. Subsidies and supports that provide respite to caregivers in terms of either time (supports) or budget constraints (subsidies) can improve caregivers’ well-being, even when subsidies do not directly target caregivers. Evidence from recent long-term care reforms in Scotland and Spain suggests that caregiver support can have a large influence on caregiver well-being and mental health [3], [4]. Vulnerable caregivers are at greater risk of caregiver strain when they do not benefit from support and subsidies. If a caregiver's health deteriorates to the point they can no longer provide care, the care receiver may be at risk of being placed in a nursing home.

Employment leaves

Caregivers have the right to take time off work, but the amount of time off varies by country, and, to date, only a few countries provide formal paid leave. Even when paid leave is formally contemplated in the legislation, it is usually for less than a month; one exception is Belgium, which allows a full 12 months. Even when paid leaves are available, the amount of such compensation varies widely; for example, in many Scandinavian countries paid leave covers between 40% and 100% of the caregiver's original wage whilst in other European countries leave periods are unpaid. In terms of unpaid leave regulation, countries can be divided into two groups based on their generosity [5], namely those allowing leaves from work for several years, including Belgium, France, Spain, and Ireland, and the UK, which only allows shorter leaves of up to three months.

Despite the increasing development of labor market regulations, descriptive data from the 2004 European Establishment Survey on Working Time and Work-Life Balance show that the uptake of these opportunities remains limited [5]. That is, even though roughly one-third of European employees have access to care leave, only a small proportion take it. In Europe, the 2004 survey finds that roughly 37% of European companies declare that long-term leave is available for employees to care for an ill family member, whereas nearly all offer parental leave and 51% of employees have taken parental leave in the previous three years. Statutory leave for carers of older adults, as well as flexible work arrangements, are much less widely available compared to similar leave to care for children. Out of 28 European countries examined, 22 offer employees some sort of statutory care leave to look after dependent older relatives. This is clearly an area where some policy interventions could improve the life of working caregivers.

Respite care and flexible work schemes

Respite care refers to support given to the caregiver rather than the care receiver and includes a break from normal caring duties for a short period of time or a long period of flexible working arrangement to overcome time constraints to caregiving. Such support may help caregivers balance care and employment obligations, either by providing carers with enough income or, alternatively, access to a social network via their employment that can improve caregivers’ emotional well-being. However, a broader definition of care leave may be desirable, even though, as in any social program, expanding subsidies and supports for caregivers may give rise to moral hazard, also known as the “woodwork” effect. Indeed, whilst parent–child relationships and the need for childcare are relatively clear, policymakers continue to struggle with determining who the caregivers of older adults are, and what level of caring commitment should trigger an entitlement to care leave. To avoid such issues, entitlements typically target the care receiver instead.

When available, statutory leave for adult caregivers is usually short in duration and often unpaid, typically lasting between two and four months. However, it can vary across countries, and in the Netherlands, the state may subsidize a portion of the income lost due to reduced working hours. However, evidence suggests that paid family leaves influence the likelihood of returning to work. Overall, this policy can have an impact, by reducing the personal and financial costs of providing care.

Tax incentives

The introduction of tax deductions for expenses incurred by families when caring for relatives is an alternative mechanism for assisting households with the funding of long-term care. Long-term care insurance premiums in the US are tax deductible to the extent that they exceed 10% of an individual's adjusted gross income. Nursing home fees are tax deductible in some countries, such as in Ireland, under certain conditions. Similarly, in Canada, federal and provincial governments offer tax credits to taxpayers, including those paid for medical expenses related to nursing and retirement homes.

Therapy and respite to caregivers

Finally, governments can design programs that provide psychological therapy and different types of support, such as financial, physical, emotional, and social, while also considering the care recipient's illness or disability. Caregivers may require additional support to maintain their motivation to continue providing care, as some care is considered “care by default” rather than the result of choice. Another issue that caregivers face is social isolation, which can have an impact on their mental health. As a result, interventions to increase caregivers’ social interactions can make a difference.

Limitations and gaps

The measurement of many caregiving arrangements is far from ideal; often, data regarding unpaid, or informal, caregiving is either not collected or is imprecisely measured in surveys and social statistical data. One way to identify caregivers is by asking individuals to self-report their caregiving status, which elicits what can be defined as “caregiver identity.” Many studies define a caregiver as someone who provides any amount of care or a specific amount (e.g. 20 hours of care per week), and high-intensity caregivers as those providing more than a given threshold (e.g. 40 hours of care per week). However, both elicitation methods deliver discrepancies in how best to measure caregiving. Some studies focus on spousal caregiving alone, which is more precisely collected in surveys. Furthermore, there are non-negligible econometric concerns in estimating the effect of caregiving on employment influenced by unobservable characteristics, anticipation or caregiving effects, and reverse causality, all of which bias the effect of caregiving on employment [7]. So far, most empirical studies rely on instrumental variable analysis, while only a few examine evidence from policy interventions, and there is barely any evidence from randomized experiments.

Summary and policy advice

The provision of care for older adults is frequently motivated by intergenerational social norms. Such norms induce individuals to sacrifice their leisure time and employment opportunities to ensure that their family members and other emotionally attached individuals do not have unmet needs. However, the supply of care can entail a significant burden in terms of forgone employment opportunities, as well as emotional and mental strain, which individuals endure to meet such intergenerational caregiving norms. Governments can impact caregivers’ monetary and emotional costs by influencing their time allocation decisions and budget constraints.

Government interventions can include regulations that increase labor market flexibility designed to ease time constraints that allow caregivers to both provide care and meet their employment obligations, as well as establishing provisions for leaves of absence. Similarly, financial incentives for caregiving can partially compensate caregivers for the opportunity costs of providing care, which are driven by labor market participation and its intensity. For instance, opportunity costs of caregiving can be influenced by the geographic distance to the care recipient. In sum, policy interventions such as those described above can enable caregivers to take time off and provide financial respite to compensate them for lost earnings and other costs associated with providing care to older adults.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Joan Costa-Font