Elevator pitch

Border enforcement of immigration laws raises the costs of illegal immigration, while interior enforcement also lowers its benefits. Used together, border and interior enforcement therefore reduce the net benefits of illegal immigration and should lower the probability that an individual will decide to illegally migrate. While empirical studies find that border and interior enforcement serve as deterrents to illegal immigration, immigration enforcement is costly and carries unintended consequences, such as a decrease in circular migration, an increase in smuggling, and higher prevalence of off-the-books employment and use of fraudulent and falsified documents.

Key findings

Pros

Border enforcement works as intended: it drives up the cost and risks associated with border crossings and deters illegal immigration.

Border enforcement results in more positively selected migrant flows, possibly due to the higher costs of crossing.

Interior enforcement lowers the benefits of migration, which should act as a deterrent.

While the cost of enforcement is a burden on taxpayers, native workers may benefit when there is less competition from migrants entering, at least in the short term.

The unintended consequences of border and interior enforcement are reduced when accompanied by other immigration reforms, such as a regularization program or a temporary worker program.

Cons

Intensified border enforcement leads to reduced circular migration, higher demand for smugglers, riskier crossings, and more migrant deaths.

Relying on border enforcement alone to keep migrants out causes wages to rise in the destination country and fall in the source country, counteracting the higher crossing costs and increasing incentives to migrate.

Interior enforcement, such as employer verification mandates, lower employment and wages among unauthorized immigrants and can result in worse outcomes for their minor children.

Additional interior enforcement can increase informal sector employment, where workers and employers evade taxation and regulation.

Immigration enforcement is costly and can divert resources from other federal and state law enforcement priorities.

Author's main message

There are many political, security, and economic motivations for limiting illegal immigration. However, enforcement measures should be designed and regularly evaluated to control costs, minimize distortions, limit detrimental impacts on migrant families, safeguard legal migration and commerce, and mitigate other unintended consequences. Enforcement can be more effective and increase the net economic benefits of immigration to the destination country if implemented together with comprehensive reform and legal migration pathways that address the underlying push and pull forces that drive unauthorized migration.

Motivation

With concerns about immigration on the rise, many governments are spending more on border and interior enforcement and increasing penalties for unauthorized migrants. Meanwhile, anti-immigrant sentiment is gaining strength throughout Europe and the US. Resentment over immigration is believed to have played a major role in the 2016 Brexit vote, which mandated the UK's exit from the EU. Concerns about illegal immigration have led to widespread support for a border wall along the US-Mexico border despite the fact that unauthorized crossings are near multi-year lows. The US, home to an estimated one-quarter of the world's unauthorized immigrants, spends close to US$20 billion per year on immigration enforcement. Despite record spending on enforcement, which includes border barriers, aerial drones, detention centers, 20,000 Border Patrol agents, and much more, polls suggest that most Americans still feel the border is not secure. Given limited budgets and unintended consequences, it may be neither possible nor desirable to secure all borders by relying solely on enforcement tools.

Discussion of pros and cons

Modeling immigration enforcement

Increasing border enforcement has been the preferred response for confronting rising numbers of unauthorized immigrants. Voters and their governments view illegal immigration as undesirable for a number of reasons. Unauthorized immigrants are typically low-skilled and relatively poor. They bring little in the way of savings to invest or formal training to put to use in the destination country labor market. In many countries, although typically not in the US, they tend to work off the books. Increasingly in recent years, they are applying for asylum. Some groups say unauthorized immigrants are more likely to commit crime but the evidence does not support that claim. Illegal immigration is also often viewed as symptomatic of the government's lack of control over the nation's borders. This is regarded as a politically unacceptable weakness in some quarters, especially in the context of concern about national defense and the need for protections against terrorism.

Governments may also intervene to protect the employment prospects of native workers. Research shows that low-skilled foreign workers have a small negative effect on competing natives’ wages. Research also shows that low-education immigrants cost more in public services than they contribute in taxes, making them a net fiscal burden on taxpayers.

In theoretical models of illegal immigration and the application of border and interior enforcement, unauthorized immigrants are usually assumed to be low-skilled and relatively poor [1]. Increased border enforcement raises the unskilled wage, which helps unskilled workers, but it also raises taxes to fund enforcement, which hurts native skilled workers. By raising the unskilled wage and thus increasing the gains from migration, border enforcement is counterproductive. Interior enforcement does the opposite, pushing down the wages of unauthorized workers (assuming that employers can distinguish between legal and unauthorized workers, which is not always the case).

By increasing the costs of migration, enforcement affects both the volume and the composition of migrant flows. Research shows that when the costs of migration are high, possibly due in part to increased enforcement, low-education, low-income workers simply may not be able to afford to migrate. For example, Mexican migrants with low levels of education are deterred more by increased border enforcement than their better-educated peers, resulting in positive selection among unauthorized migrants [2].

The migration decision

Migration can be forced, voluntary, or a combination of the two. Civil war, persecution, or famine may leave people with little choice but to migrate. With voluntary migration, theory posits that a potential migrant decides to migrate if the expected benefits—typically earnings from a job—exceed the costs, such as traveling expenses, smugglers’ fees, and the costs of adapting to the destination country [2]. This basic model falls short of explaining several well-established patterns, such as circular or return migration. Return migrants may be motivated by target saving—the desire to accumulate a predetermined sum to pay off a debt or invest in a business. Moreover, the migration decision is often made at the household rather than the individual level [3]. People may migrate to reunite with earlier migrants (network migration). People living in countries with incomplete financial markets and weak social safety nets may migrate not only to increase income but also to diversify risk to household income from economic crises, crop failures, and similar shocks. It bears noting that climate change may be contributing to the frequency and severity of some of these shocks.

Whatever the details of the migration model, migration costs figure prominently for two reasons. First, pecuniary costs have to be paid up front, which requires access to savings or credit (borrowing). Second, illegal migration is more costly than legal migration because unauthorized migrants typically pay a smuggler in addition to risking their lives. Their trips are also generally longer, which entails more foregone labor income, particularly if migrants are apprehended and detained before they are deported, as is increasingly the case along the US–Mexico border [4].

Migration models highlight the importance of the income gap, which is driven by wages and job opportunities in both destination and origin countries. There is typically a higher responsiveness of illegal than legal migration to changing economic conditions [5], [6]. This was apparent in southern Europe during the economic boom in the early 2000s (preceding the sovereign debt crisis). Unauthorized migration to the US has a long history of disproportionately large response to changes in labor demand, particularly in construction [6]. Border Patrol apprehensions are highly correlated with construction permits for single-family housing, and illegal immigration plummeted during the 2007–2009 recession and housing bust [6], [7].

In addition to business cycle factors, which tend to be temporary, there are long-term supply-side factors such as demographics. Large birth cohorts in origin countries depress relative wages as young people enter the workforce, which widens the income gap and contributes to emigration. Similarly, declining fertility rates depress population growth, speed up aging, and reduce emigration. In Mexico, fertility rates fell from 6.8 children per woman in the late 1970s to 2.2 children per woman in 2010, contributing to falling emigration and making resumption of mass emigration from Mexico unlikely [6], [7].

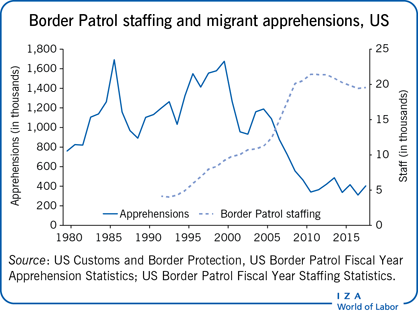

Trends in border enforcement

Tougher immigration enforcement has been the trend around the world since the 1990s. Australia implemented mandatory detention in 1992, which puts all unauthorized immigrants into detention camps while their cases are resolved, a process that can take years. In the mid-2000s, the EU implemented its own border enforcement, adding border guards and sea patrols and creating Frontex, the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union. US border enforcement rose sharply in the 1990s and 2000s, but the buildup slowed after 2010. The number of US Border Patrol agents rose from 4,139 in 1992 to 21,444 in 2011 before shrinking to 19,555 in 2018. Over this time, the Border Patrol also invested in advanced technology, including double fences, watch towers, ground sensors, remote video monitoring, and aerial and marine surveillance. By 2012, about one-third of the southwest border of the US was fenced and it remained at that level until recently when the Trump administration began building new barriers [6], [8].

There has also been a trend toward harsher punishments for migrants apprehended at US borders. Historically, the great majority of apprehended migrants were from Mexico; they signed “voluntary departure contracts,” after which they boarded a bus back to Mexico. Some observers referred to this policy as the “revolving door” of US border enforcement because the departed migrants typically attempted another border crossing within a day or two. This process repeated itself until the migrant was successful [8]. Two important changes spelled the beginning of the end of this practice. One, the Border Patrol began fingerprinting all apprehended migrants, which allowed them to identify and prosecute repeat crossers. Two, Congress began mandating harsher consequences for apprehended migrants. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, passed in 1996, implemented expedited removal, interior repatriation, and three- and ten-year admission bars for previously admitted unauthorized immigrants seeking to be admitted legally to the US. Several other initiatives followed, including “zero-tolerance” policies such as Operation Streamline, which subjects unauthorized immigrants to federal criminal prosecution [8]. So-called “zero-tolerance” and “consequence” policies implemented by the US Border Patrol increased the share of apprehended migrants subject to administrative and criminal sanctions from 15% in 2008 to 85% in 2012. While most offenses were misdemeanors and resulted in very short jail terms, the proliferation of zero-tolerance practices along the US–Mexico border marks a dramatic shift from the days of voluntary departure.

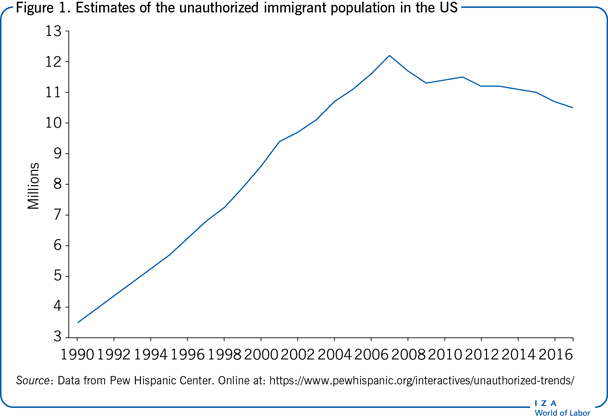

During the massive border buildup and implementation of tougher consequences, migrant apprehensions first rose sharply, peaking at 1.7 million (rounding) apprehensions in fiscal 2000, and then plummeted, averaging just below 400,000 from 2011 to 2018. Meanwhile, the estimated unauthorized immigrant population rose from 3.5 million to 12.2 million between 1990 and 2007 before declining to 10.5 million in 2017 (Figure 1) [7]. The US is home to an estimated one-quarter of the world's unauthorized immigrants. Not all of them cross the border illegally, however. In fact, in recent years more unauthorized immigrants have overstayed visas than entered the country illegally [8].

Is border enforcement an effective deterrent?

Border enforcement, by increasing the probability of apprehension or the severity of punishment, should deter illegal immigration. Despite this clear prediction, the US experience since the 1990s suggests that massive increases in border enforcement are consistent with both rising and falling inflows of unauthorized immigrants. Clearly, border enforcement is just one of many migration determinants.

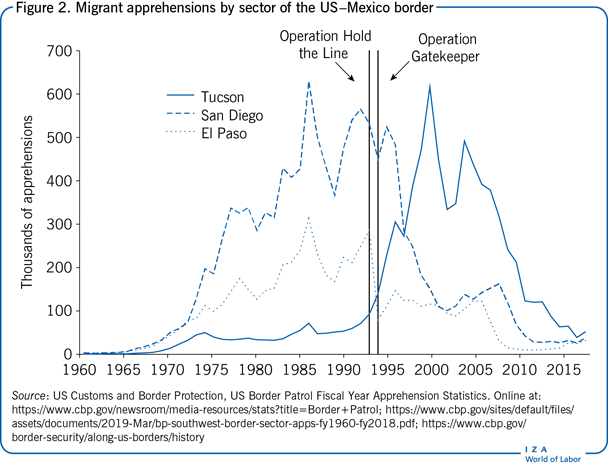

The first attempts at border buildups were likely more effective in diverting migrants than deterring them [3]. Earlier studies on Mexico–US migration find little direct evidence of deterrence effects of border enforcement on migration but considerable evidence of migrants’ adaptive behavior. For example, large, localized ramp-ups in border enforcement in the US such as Operation Hold the Line in El Paso in 1993 and Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego in 1994 led to steep declines in migrant apprehensions in these sectors but increases in Tucson (Figure 2) [3]. Instead of crossing through urban areas in West Texas and Southern California, migrants went through the deserts of Arizona [3]. Later, when the Border Patrol cracked down on the Arizona border, migrants shifted to South Texas. By forcing migrant crossings to desolate or dangerous areas, US Border Patrol increased the risk of migrant injury and death. Enforcement also encouraged other adaptive behavior, such as inventive crossing techniques, including the use of decoys and tunnels.

Increased US border enforcement has had several other effects that also deter migration. The probability of using a smuggler increased from 80% in 1990 to 90% in 2012, perhaps because fewer migrants were willing to cross alone through the wilderness [8]. Smuggler fees also rose along with demand, and successful crossings grew more difficult and took longer [4]. Migrant surveys, such as the Mexican Migration Project, indicate that smuggler prices for Mexicans rose in inflation-adjusted terms from less than US$1,000 a trip in the 1980s to over US$5,000 in 2013. Only some of the increase can be attributed to more border enforcement, however, and the rest to other demand and supply factors. One study found that the border buildup between 1986 and 2004 raised smugglers’ prices by only 17% while increasing crossing time by two to five days [4]. Higher smuggler and opportunity costs should translate into a lower probability of migrating. Indeed, another study found that a 20% rise in smugglers’ prices led to a 13–21% decline in the probability of migrating [8].

Among studies that measure the direct relationship between border enforcement and illegal immigration, one set of estimates suggests that a 10% increase in Border Patrol linewatch hours reduces illegal inflows by 4–8% and that this effect increases over time [9]. Another study finds that a 0.5 million increase in linewatch hours—the average increase between 1990 and 2003—reduced intentions to re-migrate among a sample of male return migrants by roughly 14% [10]. Tougher border enforcement is also correlated with lower wages in Mexican border cities, suggesting that enforcement prevents or delays illegal entries into the US [5]. Taken together, these findings show that border enforcement is an effective “at the border” deterrent—increasing Border Patrol watch hours reduces the probability that migrants intend to repeat border crossings or delays their attempts [6]. Studies that find that border enforcement raises smuggling prices and thus depresses migration at the origin document a form of “behind the border” deterrence, which prevents the potential immigrant from attempting a crossing [6].

Trends in interior enforcement

Interior enforcement has been ramped up in many countries, but perhaps nowhere as drastically as in the US, which deported a record three million immigrants from 2010 to 2017. Record deportations are partly the result of new programs that have incorporated state and local police into federal immigration enforcement efforts. The impetus for this change was the 287(g) provision in the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) under which state and local police departments could opt to be trained and deputized to enforce federal immigration laws. Another program, Secure Communities, came later—in 2008—but was in place nationwide by 2013. Secure Communities checks the records of arrested individuals against immigration databases [6]. Research has linked Secure Communities and the 287(g) program to hundreds of thousands of deportations but also to adverse outcomes for immigrant families, including worse labor market and health outcomes, increased home foreclosures, separation of children from their parents, higher probability of children dropping out of school and of grade retention (repeating an academic year of school), among others.

Employers have also been targeted. While the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 made it illegal to hire unauthorized immigrants, the law was rarely enforced. This changed with E-Verify, which allows employers to check the legal working status of new hires against Social Security records and a federal immigration database. E-Verify is now mandatory for federal government contractors and is used to varying degrees in over 20 states. Although most states do not require that employers use E-Verify, estimates suggest over half of all new hires in the US go through it.

Several studies have found that state-level universal E-Verify requirements reduce the population of unauthorized immigrants and worsen their labor market outcomes. For instance, implementation of the 2007 Legal Arizona Workers Act, which requires all employers to use the E-Verify program, resulted in a large shift out of wage and salary employment and into self-employment among non-citizen Hispanic immigrants, a group with a high share of unauthorized workers [11]. Another empirical analysis finds that E-Verify mandates more broadly severely reduce hourly earnings of immigrants who are most likely to be unauthorized, suggesting that such programs may be successful in reducing the rewards of illegal immigration [12]. Meanwhile, there is some evidence that E-Verify raises wages for competing groups of US workers, including Hispanic natives and naturalized immigrants.

Unintended consequences

Interior enforcement can lead to negative fiscal impacts, document fraud,and harm families

As theory suggests, an important advantage of interior enforcement over border enforcement is the negative effect on unauthorized workers’ wages, which reduces labor market pull factors and should deter future migration [1]. Does it follow that these policies encourage unauthorized immigrants to leave and return to their country of origin? Immigrants may leave the states where these policies are implemented, but there is little evidence that a policy such as E-Verify will make them leave the country [11]. Unauthorized workers make up about 5% of the US labor force; a majority of these workers are long-time US residents and many of them have children who are US citizens.

Falling household income and employment resulting from E-Verify and other interior enforcement policies are more likely to lead to increasing needs for public assistance than to emigration. At the same time, unauthorized immigrants’ tax contributions will decline, as these workers may be diverted into self-employment or into the informal sector, where workers and firms do not pay taxes and employers likely skirt health and safety laws. Implemented universally and in the absence of a legalization program, interior enforcement policies such as E-Verify or removal programs such as Secure Communities can worsen the negative fiscal impact of illegal immigration and slow immigrant assimilation. As noted above, research has linked removal programs to a host of negative outcomes for migrants and their children, including in health and education.

Another likely consequence of electronic verification policies in particular is a surge in fraudulent and falsified documents. Identity fraud can undermine the accuracy of interior enforcement programs that do not apply biometric measures, such as fingerprints or photographs, as a safeguard. Reports have found that identity fraud was the main driver of inaccuracies in E-Verify—in its early stages, the program gave authorized employment to 54% of unauthorized workers screened.

Border enforcement can lead to rising deaths and longer migration spells

Border enforcement has unintended consequences in addition to its intended effect of stopping and deterring illegal immigration. The US Border Patrol's strategy of pushing migrants to more remote areas of the border has led to rising death rates, often from dehydration or exposure to extreme temperatures [3], [8]. Death rates among migrants rose an estimated threefold in the late 1990s following implementation of Operation Hold the Line and Operation Gatekeeper [3]. Despite large declines in illegal immigration since 2000, deaths have likely not fallen but have probably continued to rise. In Europe, deaths among unauthorized migrants reached record levels in recent years and now far exceed fatalities in the US. According to UN Refugee Agency estimates, over 2,000 migrants drowned or went missing while attempting to cross the Mediterranean in 2018.

The most commonly cited and widely documented unintended consequence of increased border enforcement is longer migration spells and reduced circularity. In the US, border enforcement as measured by US Border Patrol linewatch hours has a significant negative effect on migrant outflows to Mexico, as well as inflows, which implies that tougher enforcement increases the duration of stay by deterring return migration. That encourages more permanent settlement among unauthorized immigrants from Mexico [9].

Among those who illegally cross borders, the demand for smugglers has grown commensurate with rising border controls. This may expand the role of organized crime in illegal immigration. At the US–Mexico border, drug cartels seem to be engaging increasingly in the business of human smuggling, particularly of Central Americans [8]. This incursion may represent a national security issue as well as increase the danger to migrants themselves, as the flows of illegal goods become more closely entwined with crossings of unauthorized migrants.

Another consequence of tighter controls on illegal entry is increased attempts to enter legally, whether it is through visa overstays or seeking asylum. The surge in Central American asylum seekers along the US–Mexico border in 2018–2019 is partly related to tighter border enforcement and the difficulties of illegally migrating. In Europe, many irregular migrants file asylum claims even though they lack the grounds to do so and are in fact economic migrants.

Finally, increased enforcement can have a chilling effect on legitimate commerce; to the extent that ramp-ups in border security are associated with increased wait times at ports of entry, which may slow and even deter the legitimate flow of goods and people across borders, harming regional and national economies. In countries with long mountainous and maritime borders, such as Italy, Greece, and Spain, heavily fortified roads and ports may deter tourism, an important source of income. More generally, distributing more border patrol resources toward enforcing immigration laws rather than toward facilitating commerce may have adverse economic consequences.

Limitations and gaps

Quantifying the costs and benefits of immigration enforcement from a policy perspective requires reliable data on its application and outcomes. A 2013 National Research Council report in the US urged the Department of Homeland Security to gather and release more detailed and frequent data on staffing, apprehensions, and migrant characteristics. This would allow independent researchers to better model border crossing attempts and develop measures of enforcement effectiveness [8]. The report also urged the three immigration enforcement arms within the department to integrate their databases.

Integrating data on border and interior apprehensions would allow researchers to track individuals and enforcement initiatives over time and across space, which could provide valuable insights into migrant destinations and the relative effectiveness of border and interior enforcement. Administrative data could then be combined with survey data in the origin and destination countries to look at migrant populations before, during, and after migration.

Given the clandestine nature of illegal immigration, the National Research Council recommendations are relevant for all immigration destination countries. No one survey or set of administrative data can adequately describe this population and its interactions with law enforcement. Moreover, given the extent of adaptive behavior, as well as constant modifications to enforcement, any model of illegal immigration has to be dynamic and frequently tested against the data.

Summary and policy advice

Immigration enforcement is necessary—the political and economic motivations for limiting illegal immigration are numerous. However, considering the high costs of implementing enforcement and the considerable human costs of dispensing it, enforcement measures should be carefully designed and regularly evaluated. Immigration policy should also take into account conditions in origin countries. Work-based migration can be accommodated with a temporary visa or guest worker program, while humanitarian migration may require other measures.

Efficient enforcement minimizes distortions, controls costs, limits detrimental impacts on families, shields legal migration and commerce, and mitigates unintended consequences. In many countries, comprehensive immigration reform that combines efforts to create legal pathways for migration with improvements in enforcement methods can ease pressure at the border and in the interior, while increasing the net economic benefits of immigration to the destination country. Governments can aid research in this area by gathering and publicly providing consistent, comprehensive, and timely data on migration and enforcement.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee, the IZA World of Labor editors, and Carlee Crocker and Chloe Smith for research assistance. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System. Version 2 of the article updates the figures and the text, including fully revising the “Trends in interior enforcement” section, and updates the “Further reading” references.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Pia Orrenius