Elevator pitch

A considerable share of the labor force consists of underemployed part-time workers: employed workers who, for various reasons, are unable to work as much as they would like to. Offering unemployment benefits to part-time unemployed workers is controversial. On the one hand, such benefits can strengthen incentives to take a part-time job rather than remain fully unemployed, thus raising the probability of obtaining at least some employment. On the other hand, these benefits weaken incentives for part-time workers to look for full-time employment. It is also difficult to distinguish people who work part-time by choice from those who do so involuntarily.

Key findings

Pros

Benefits to part-time unemployed workers strengthen incentives to take on part-time jobs.

Subsidized part-time employment can be a stepping stone toward unsubsidized employment.

Compared with many other systems, unemployment insurance for part-time workers seems to work well as an active labor market policy.

Evidence suggest that the positive effect might be largest for disadvantaged workers.

Unemployed workers who move into part-time jobs receive higher earnings, pay higher taxes, take less from the unemployment insurance system, and may receive fewer means-tested benefit transfers.

Cons

If part-time unemployment benefits are too generous, they create a risk for prolonged part-time unemployment spells.

Benefits to part-time unemployed workers weaken incentives to move into full-time employment and can cause lock-in effects.

Benefits to part-time unemployed workers could function as an unintended indirect subsidy to sectors with many involuntary part-time workers.

It is difficult for the government to distinguish people who are looking for full-time work from people who work part-time by choice.

Author's main message

For workers who would prefer full-time work, part-time jobs are a stepping stone to regular employment. Thus, partial unemployment benefits for part-time unemployed workers could yield significant welfare gains; they could also lower government spending on unemployment insurance and other transfers to these workers. As an active labor market policy, part-time benefits seem to work rather well, especially for marginal groups. To counteract the tendency for high benefits to discourage moving from part- to full-time jobs, the benefits should be of short duration and decline over time. Time-limited benefits not only increase incentives for full-time unemployed to move into part-time work, but also to move quickly on to full-time employment.

Motivation

The majority of workers prefer permanent full-time jobs. However, temporary or part-time jobs might be easier for unemployed workers to obtain. Indeed, involuntary part-time workers, who would prefer full-time work, make up a considerable share of the labor force. Still, a part-time job is often regarded as better than no job. Part-time jobs can build the human capital and networks that part-time unemployed workers need in order to succeed in obtaining full-time jobs, and they can lessen the stigma of full-time unemployment. Therefore, many countries allow unemployed workers to accept part-time jobs and still be eligible for partial unemployment insurance. Among the countries with partial unemployment insurance are the US, the Nordic countries, and many other European countries.

Despite discussions of the benefits of partial unemployment insurance to part-time unemployed workers and the common occurrence of part-time unemployment, there is surprisingly little research on unemployment insurance that deals with partial unemployment benefits. One reason might be that part-time unemployment is considered less of a problem than full-time unemployment. Another reason might be the lack of data. In many countries, part-time unemployment is not regularly measured. Furthermore, it is often difficult to obtain data on part-time workers who collect unemployment insurance.

Discussion of pros and cons

What is part-time unemployment?

Part-time unemployment is commonly defined as the underemployment of workers who are willing and able to work additional hours but who work less than full-time in a given week. However, part-time unemployment could be defined over a longer time period. In that case, seasonal unemployment would be included in the definition of part-time unemployment. Indeed, many temporary workers return to their original employers after periods with no work.

Part-time unemployed workers may or may not qualify for unemployment benefits. Most European countries and the US provide partial unemployment benefits to workers if the number of hours worked and their wage income are below certain thresholds. However, partial unemployment insurance could also include individuals who work full-time on short-term contracts and collect benefits in the periods between work contracts. Another related topic is short-term work compensating schemes, most prominently in Germany. These schemes compensate workers for income loss while on shortened hours. One argument for providing these schemes during a recession is to help maintain employment during harder times. However, they may also impede necessary reallocation and structural change in the labor market.

Part-time unemployment in Europe

This article is concerned with the primary definition of part-time unemployed workers: workers who are willing and able to work additional hours but who work less than full-time in a given week.

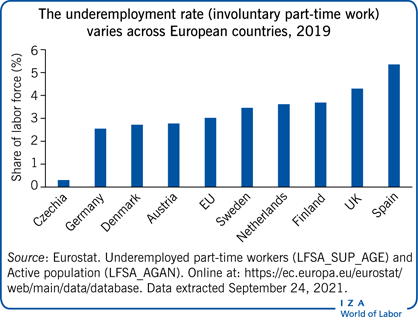

In 2020, almost 20% of employed workers in the EU reported that they worked part-time. Part-time work is most common in the Netherlands, where half of all employees work part-time. Generally, part-time work is unusual in Eastern Europe. Women are far more likely than men to report part-time work. Almost one in three employed women worked part-time in 2020, but only around one in ten men did. On average, part-timers work around 20 hours a week.

Many people who work part-time do so by choice. However, a large share of part-time workers want to work more than they do. The share of involuntary part-time workers has decreased over the last decade and less than one out of four part-time workers were involuntary part-timers in 2020. That corresponds to around 6.5 million workers that were part-time unemployed, and they accounted for 3% of the labor force in 2020.

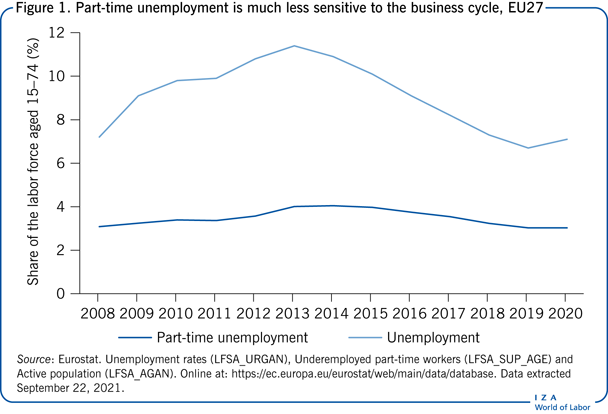

Part-time unemployment increased in the aftermath of the Great Recession (Figure 1). However, compared with full-time unemployment, part-time unemployment is much less sensitive to the business cycle. Both part-time and full-time unemployment peaked in 2013. By that time, part-time unemployment had increased 1.2 percentage points since 2008, compared with 3.9 percentage points for full-time unemployment. During the coronavirus crisis in 2020, only full-time unemployment increased.

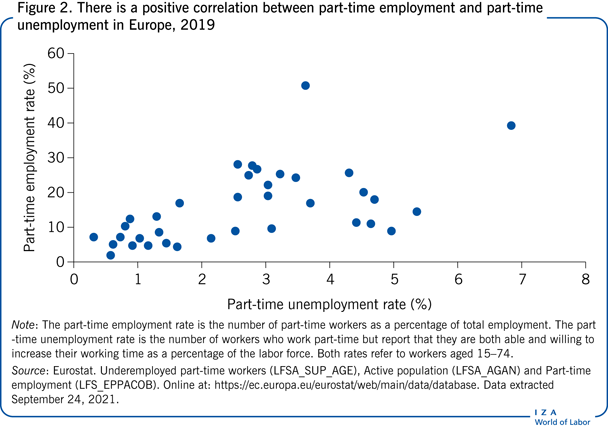

Generally, countries with a high share of part-time workers also have a high share of part-time unemployed workers (Figure 2). In part, this strong correlation between the share of part-time employment and the share of part-time unemployment might be mechanical. If part-time employment rates are high, naturally more workers could be part-time unemployed.

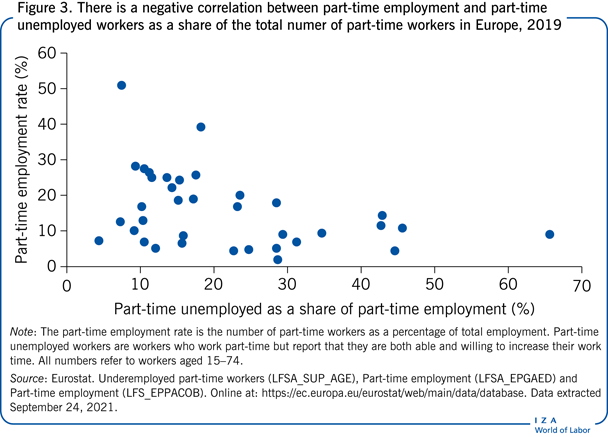

However, Figure 2 does not necessarily imply that part-time workers are more likely to be part-time unemployed workers in countries where the share of part-time employment is high. Indeed, the correlation is negative between part-time employment and part-time unemployed workers as a share of the total number of part-time workers (Figure 3). Where part-time employment is less common, a larger share of those workers are involuntary part-time workers. One explanation for this result could be that part-time work is associated with a larger stigma in countries where part-time work is uncommon.

Transition to full-time work

There is a large literature on the transition from non-regular employment, mainly temporary contract work, into regular employment. The consensus seems to be that non-regular employment might be a stepping stone to regular employment. A similar argument can be made for part-time jobs.

While the human capital of an unemployed worker declines, the human capital of an unemployed worker who takes on a part-time job increases. A part-time job is also a good opportunity to build networks and perhaps even to gain regular full-time employment at the place of part-time work. Having part-time work lifts some of the stigma associated with unemployment; part-time work may also be easier to obtain than full-time work [1]. The longer a person is unemployed, the lower the probability of getting a call-back on a job application or an interview [2]. In that context, offering part-time benefits can be viewed as an active labor market measure. Part-time unemployment benefits incentivize unemployed workers to remain engaged in the labor market. Compared with the success rates of many other approaches to unemployment, the transition rates from part-time unemployment to regular employment seem fairly high.

However, there is a significant risk of lock-in effects in part-time unemployment. Part-time work may distract workers from more productive job search activities. Working part-time and receiving a top-up on your income through partial unemployment benefits might be an attractive option for some workers, thus reducing the incentive to search for full-time employment. When part-time work becomes more attractive, some unemployed workers might also focus their job search activities on part-time jobs, thus short-circuiting or delaying the transition to full-time employment. These lock-in effects may also increase the overall cost of unemployment insurance.

Indeed, part-time unemployed workers are less likely to apply for additional work than unemployed workers are to apply for a job. Furthermore, many part-time unemployed workers do not actively engage in job search activities in the labor market but rather seek to increase the number of hours they work at their current job [3]. In addition, some part-time workers adjust their labor supply to gain from combined earnings and benefits, and these effects could be widespread [4]. Therefore, it might be even more important to monitor the job search activities of part-time unemployed workers claiming benefits than it is to monitor those of unemployed workers who are receiving benefits.

In-work benefits and unemployment insurance

Benefits to part-time unemployed workers can also be viewed as an in-work benefit that boosts incentives to move from unemployment to employment. For example, in the US in the late 1980s and early 1990s, raising the earnings ceiling for unemployment benefits eligibility shortened unemployment spells and increased the probability of getting a part-time job [5]. The transition rates from full-time unemployment to part-time unemployment rose for workers early in their unemployment spell, suggesting that part-time benefits could reduce the risk of long-term unemployment. However, although providing unemployment benefits to part-time workers improves incentives for unemployed workers to accept part-time employment, these benefits also reduced incentives to move on to full-time employment.

In a search-and-matching framework—a model that relates workers searching for jobs and firms with vacancies—part-time benefits increase transitions from unemployment to part-time work and decrease transitions from part-time to full-time employment [6]. The result is a rise in part-time employment and part-time unemployment and a decline in full-time employment. One way to counteract the smaller outflow from part-time unemployment to full-time employment as a result of providing unemployment benefits for the part-time unemployed would be to introduce time limits on the benefits. There is a non-negligible welfare gain associated with time-limited part-time benefits, with the size of the welfare gain dependent on how responsive wages are to part-time benefits.

Empirical evidence

There is a growing literature on part-time benefits. Many European studies employ a timing-of-events approach to control for the selection effects into part-time unemployment. In general, fully unemployed workers differ from part-time unemployed workers. For example, some studies find evidence of a negative selection effect into part-time unemployment; fully unemployed workers move to full-time employment more quickly than part-time unemployed workers [7], [8]. Unemployed workers with good job prospects are less likely to accept part-time work than workers with worse prospects. In many countries, there is a wage penalty associated with part-time jobs. However, a recent Australian study finds a wage premium associated with part-time work once the study controls for differences among workers [9]. Therefore, it is important to deal with selection effects to be able to determine the effects of part-time unemployment insurance.

The question studied the most is: are part-time jobs with benefits dead-ends or helpful stepping stones to regular employment? The timing-of-events approach, however, relies on strong assumptions about the unobserved variation and cannot estimate the causal effect of part-time unemployment schemes as such. To be able to estimate a causal effect from the part-time unemployment insurance system, natural experiments or randomized control trials are needed.

Using the timing-of-events approach, a Norwegian study concludes that part-time benefits reduce the time until self-supporting employment, and it finds no lock-in effects [7]. This positive effect is driven mainly by higher transition rates into regular employment during the first month of part-time unemployment when the study finds an increase in transitions to high-quality jobs. Thus, employers appear to use part-time work as a screening device when hiring workers from unemployment. More than 80% of workers transitioning from part-work to regular work did so at the same employer. In addition, part-time benefits reduced the total amount the government spends on unemployment benefits as the benefits are lower for part-time unemployed workers than for full-time unemployed workers. Similar results are found for other countries. Subsidized part-time jobs for unemployed workers are a stepping stone toward regular employment for men in Finland and for young women in Belgium [8], [10]. Neither study finds evidence of lock-in effects.

In contrast, a Danish study finds significant lock-in effects in part-time unemployment [11]. The Danish system of unemployment benefits is more generous than the other systems studied. In Denmark, the transitions into full-time jobs decrease significantly right after entry into part-time jobs eligible for partial unemployment benefits. However, after the period of part-time unemployment, the transitions to full-time jobs increase, suggesting that part-time work makes unemployed workers more hireable. The results differ between groups. Providing benefits for part-time unemployed workers seems most helpful to young workers and immigrant workers, for whom it serves mainly as a stepping stone to full-time employment and reduces unemployment spells. Workers who already have strong ties to the labor market gain less and experience the largest lock-in effects.

Similarly, a French study also finds significant lock-in effects [12]. The authors exploit people's limited knowledge of the part-time benefit system by sending out information about part-time unemployment insurance to the treatment group, while the control group received no information. Thus, it is possible to estimate the causal effect of the part-time benefit scheme in France. Another advantage of this method is that the effect of part-time benefits on unemployed workers can be estimated. The authors find that more unemployed workers move to part-time jobs when they are aware of the possibility of obtaining benefits while working part-time, but also that more workers remain (part-time) unemployed for longer. They conclude that these lock-in effects lead to an increase in the overall cost of unemployment insurance in France. In contrast, another French study shows that atypical work increases the likelihood of finding regular work when using a timing-of-events approach [13]. No lock-in effect is found and individuals with weak ties are found to gain the most from an atypical job.

Adding to the literature on government spending and externalities, a study from the US concludes that transferring income through an increase in weekly benefits is more efficient than reducing the implicit tax rate [14]. The authors of this study use a randomized experiment in Washington State, in the US, in the mid-1990s as well as a regression kink design to estimate the casual effect. They also show that the choice of estimation method has a large impact on the results.

These empirical studies suggest that providing unemployment benefits for part-time jobs can create a stepping stone to regular employment. Government spending on unemployment insurance may also fall when unemployed workers gain some earnings in the labor market. Unemployed workers who move into subsidized part-time jobs receive higher earnings, make smaller withdrawals from the unemployment insurance system, and may also receive lower means-tested benefit transfers. In addition, they contribute to production and pay higher taxes. However, providing benefits to part-time unemployed workers also seems to produce some negative effects for experienced workers, increases part-time unemployment, and could raise government spending. The nature of these effects depends on the context and how the incentives are designed. Thus, the exact rules and regulations for unemployment benefits for part-time unemployed workers matter.

Indirect subsidies of businesses with many part-time unemployed workers

Part-time unemployment benefits may work as an indirect subsidy for businesses with high levels of involuntary part-time workers, which can have adverse effects on competition. While the prevalence of this effect has not been studied, a possible way to deal with such indirect subsidies is through an experience rating system. In an experience rating system, employers’ contributions to unemployment insurance vary with the number of their previous employees who are collecting unemployment benefits. Experience rating has been in place in the US for decades [15].

Experience rating is controversial. In countries with strict employment protection legislation, firms already face an implicit tax on layoffs. Also, if the experience rating depends on the length of former employees’ future unemployment spells, firms might discriminate against job applicants who have a high probability of experiencing long-term unemployment. On the other hand, with this kind of system, firms with many part-time unemployed workers claiming benefits would have to contribute to their financing. Therefore, the case for experience rating seems to be stronger for part-time unemployed workers than for full-time unemployed workers. Experience rating for part-time unemployment insurance lowers the risk of indirectly subsidizing sectors with a large share of part-time workers; at the same time, experience rating for employees who are part-time unemployed may have less detrimental effects on selective labor demand.

Limitations and gaps

In addition to the effect of indirect subsidies on businesses with high levels of part-time workers, another issue that has not been closely examined concerns how to distinguish involuntary part-time workers from people who work part-time voluntarily. If part-time unemployed workers have access to unemployment benefits, some voluntary part-time workers might also try to claim these benefits. A simple search-and-matching model suggests that part-time benefits might still be advisable even if it is impossible to distinguish between these two groups [5].

Summary and policy advice

All in all, it appears that making unemployment benefits available to part-time unemployed workers can have beneficial effects on the labor market as well as for unemployed workers. Unemployment benefits for the part-time unemployed increase incentives for unemployed workers to move into part-time jobs, which can work as a stepping stone to full-time work. However, the beneficial effects depend on the design of the unemployment insurance scheme. The positive stepping-stone effects are more pronounced early in the part-time unemployment period. Providing benefits to part-time unemployed workers has also been shown to reduce the risk of long-term unemployment. However, there is a risk that benefits to part-time unemployed workers will reduce their search efforts while they are working part-time, which prolongs their unemployment spells. Several studies show that the stepping-stone effect is more pronounced for groups with weaker ties to the labor market; for example, young workers, immigrants, and long-term unemployed.

Therefore, the optimal system includes time-limited benefits to part-time unemployed workers, in order to encourage them to take up part-time work but also to continue to search for full-time opportunities. To lower the risk of moral hazard, it is also advisable to monitor the search behavior of part-time unemployed workers, to ensure that they are actively looking for full-time work.

Part-time jobs are often viewed as low-quality jobs with lower wages and fewer prospects than full-time jobs. However, part-time workers differ from full-time workers. Part-time jobs are considered better than no job, especially for workers in those jobs, after differences between the two groups are accounted for. Some evidence suggests that part-time jobs are at least as good as full-time jobs for the group of workers who are mainly in part-time jobs, although the research is mixed on this topic.

The optimal design of a part-time unemployment benefit system depends on country-specific factors. However, policymakers should keep in mind that part-time unemployment insurance aims at reducing the risk for long-term unemployment, reducing human capital losses during unemployment, and establishing a stepping stone to self-sufficiency. Therefore, it is important that supplementary benefits are of short duration and that the search efforts of part-time unemployed workers are monitored more closely than the search efforts of unemployed workers.

In many respects, providing partial unemployment benefits for part-time jobs can also be viewed as an active labor market policy. Thus, it might be advisable to direct these benefits to workers with weaker connections to the labor market.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of Nordea. Version 2 of the article introduces a new “Pro,” updates the figures, includes new research on lock-in effects and the results of these policies for disadvantaged groups, and adds new “Key references” [1], [4], [12], [13], [14].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Susanne Ek Spector