Elevator pitch

Government schemes that compensate workers for the loss of income while they are on short hours (known as short-time work compensation schemes) make it easier for employers to temporarily reduce hours worked so that labor is better matched to output requirements. Because the employers do not lay off these staff, the schemes help to maintain permanent employment levels during recessions. However, they can create inefficiency in the labor market, and might limit labor market access for freelancers and those looking to work part-time.

Key findings

Pros

Short-time work compensations reduce layoffs and make it easier for employers to adjust their workers’ hours to meet work requirements.

Because fewer people lose their jobs, both the employer and the state pay less in unemployment benefits.

Used in downturn periods, compensation schemes are particularly beneficial for permanent workers, who can continue in steady employment.

Short-time work compensation schemes benefit companies, because they allow them to retain valuable staff during downturns.

Cons

Compensation schemes are not beneficial to temporary workers, who do not qualify for payments and may be excluded from the labor market.

By distorting the labor market, short-time work compensation schemes can lead to inefficiency; reductions in working hours negotiated may not match the demand for labor.

Because jobs are retained when there is no demand, the schemes inefficiently reduce the reallocation of labor to more productive jobs.

Compensation schemes are not necessarily the most effective way of adjusting hours and labor costs during a recession; company-level bargaining over hours, wages, and employment may provide a better-tailored outcome than a state-sponsored scheme.

Author's main message

Short-time work compensation schemes can help employers to adjust labor to match demand during temporary periods of low demand such as recessions. They work well when unemployment benefits are generous, because they reduce their take-up. They are also effective when there are strong labor regulations and market institutions which make it difficult to adjust hours and wages at the plant level. However, they need to be designed and used with care, because they can lead to inefficiency. Workers might be retained when they should instead be made redundant, and the schemes hinder the reallocation of workers to more productive jobs.

Motivation

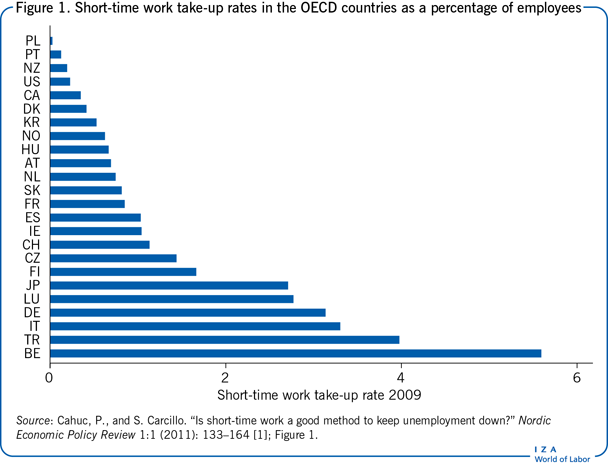

In Germany, Japan, and Italy, more than 4% of the labor force were on a short-time work compensation scheme in 2009, in the trough of the recession (Figure 1). When such schemes are offered, there is a strong take-up. But do the schemes have a positive economic effect? Do they help to reduce unemployment levels? Or do the distortions they cause in the labor market have a negative effect that outweighs their advantages? To discover that, we need to look at their theoretical and practical implications.

Discussion of pros and cons

Background

In periods of recession, many enterprises find there is less demand for their goods or services. This can make it difficult or impossible for them to retain their full workforce and continue to operate profitably. They face the alternatives of either laying off some of their employees, or reducing their working hours.

Redundancies often involve considerable cost, particularly when labor market regulations hinder companies from making them, and paying these costs can have a long-term effect on profitability. In addition, if valuable staff are lost, it is often both difficult and expensive to replace them once demand recovers. It can take a long time for the enterprise to return to its pre-recession levels of output and profitability, and in some cases it will never do so.

Requesting—or requiring—workers to reduce their hours of work can also be difficult, however. Workers and their representatives often strongly resist such requests, because of the loss of income involved. A reduced income will affect people's standard of living, and could make it difficult or impossible for them to meet commitments such as mortgage payments.

Short-time work compensation schemes provide additional funds so that employees can reduce their hours of work without a proportional reduction in their take-home pay. The employees earn less than they do when in full-time employment, but more than they would receive in unemployment benefits. The cost of supplementing the employee's income is typically shared by the employer and the state.

The state input means that in some circumstances employers can afford to retain employees even when the requirement for their labor is lessened. It also means that in some circumstances people remain in their jobs when otherwise they would have accepted redundancy or sought work elsewhere. There is of course a cost to the state of running such a scheme, although it may be less than if unemployment compensation were paid, and this must be taken into consideration.

In addition, any such scheme represents a distortion in the labor market, and such a distortion leads to inefficiencies. Because the enterprise might be retaining more staff than are required by its level of demand, it will not operate as profitably as if demand and labor were perfectly matched in an open labor market. Any such scheme also disadvantages those who cannot use it: for instance, those without full-time permanent jobs may find that those with subsidized jobs hinder their own entry into the labor market. Further, it is difficult or even impossible to distinguish between temporary shocks, from which a recovery can be expected, and longer-term movements. Some employees will be subsidized to carry out a job for which the previous level of demand will never recover. Employees might also be deterred from moving from jobs in declining markets to jobs in markets that are growing, and this too acts as a brake on the economy.

Research into countries and regions where a short-time work compensation scheme has been introduced, and comparisons between different schemes, and with countries and regions that have no such scheme, can help to clarify these different effects, and suggest the circumstances in which a scheme proves beneficial overall. It can also suggest how a scheme can best be designed to maximize its advantages and minimize its negative effects.

Germany, Japan, and Italy are examples of countries that have been affected by a strong decline in output while unemployment has increased only moderately, if at all. They have also used short-time work compensation schemes during the Great Recession of 2008–2009. This suggests that these schemes might have a positive effect, and these apparent successes have led to a renewal of interest in them. But to discover whether the apparent success is real, it is necessary to look at earlier research into the consequences of introducing this type of scheme.

The effect in stabilizing employment and reducing unemployment

The first study to yield systematic cross-country evidence about the consequences of short-time schemes compares aggregate adjustment patterns in employment and hours worked across countries and over time, using quarterly time-series data for Belgium, France, Germany, and the US [2]. In Belgium, France, and Germany, short-time compensation schemes were in operation during the research period; there was no such scheme in operation across the US.

All of these countries experienced a recession and downturn in demand, and in all of them working hours were adjusted to compensate for the fall in demand, at a level that appeared to be similar in all of the countries. However, the pattern of adjustment was different in the European countries from that in the US. The adjustment of employment to changes in output was much slower in the German, French, and Belgian manufacturing sectors, and the adjustment of hours worked was much faster in these countries.

This suggests that in the European countries the adjustment was achieved by reducing the hours of people in work, while in the US it was achieved by reducing the number of people in work (by a mixture, that is, of stopping hiring and redundancy). Both results indicate that the short-time work schemes stabilized employment, while hours of work could be adjusted in a highly flexible way to account for the change in production [1].

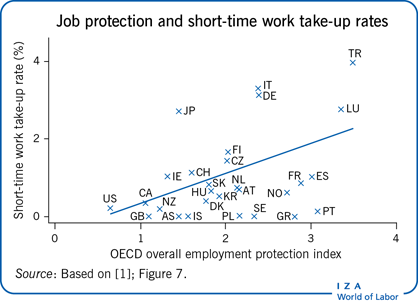

It has been argued that measures to facilitate alternatives to layoffs, such as work-sharing and short-time work compensation schemes, are typically found in countries where there are strong job security regulations [2]. Because it is more difficult and expensive to make staff redundant, there is understandably more motivation to find alternative ways of reducing the amount of labor that employers pay for.

These results are confirmed in research from 1994 based on a set of ten OECD countries over the period 1969−1988 [3]. It was found that countries with strong job protection saw the same overall level of adjustment in hours of labor as those with flexible labor regulations, like the US. So this too suggests that working-time adjustment was used to compensate for restrictions on firings.

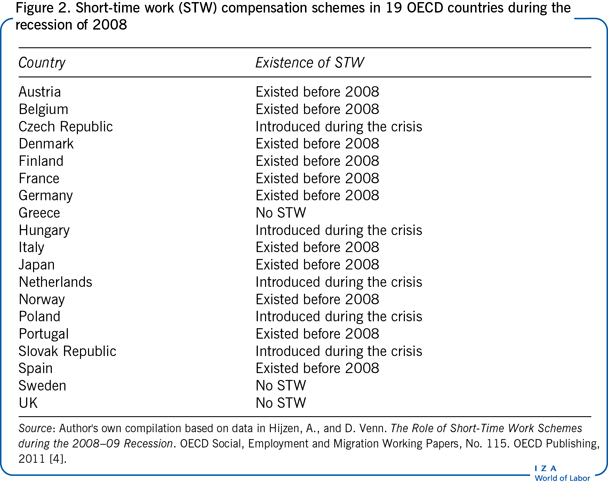

A further study looked at a period (2003−2009) which included the 2008−2009 recession [4]. The aim was to analyze the quantitative impact of short-time work compensation programs on employment and average hours, using cross-country and time variation in take-up rates. The analysis was based on quarterly data for 19 OECD countries and four industries (manufacturing, construction, distribution, and business services). It distinguished between permanent and temporary workers.

As Figure 2 shows, 11 of the 19 countries operated a short-time work compensation scheme during the entire period, five countries introduced a new scheme during the financial crisis, and three countries had no short-time work compensation scheme during the research period. Several countries (e.g. France, Germany, and Japan) relaxed the eligibility criteria for their schemes during the 2008−2009 recession [1].

Findings support the conclusion that short-time work compensation programs had an important impact on preserving permanent jobs during the economic downturn [4]. The largest proportional impacts were in Germany and Japan, where 0.7−0.8% of jobs were saved. In contrast, short-time work compensation seemed to have no significant impact on either the employment or the average hours of work of temporary workers. This research thus suggests that the positive effect on permanent jobs is not countered by a negative effect on temporary jobs [1].

Since governments and social partners purposefully improved access to short-time work compensation schemes in order to limit the loss of jobs during the recession, the correlation between short-time work compensation and employment might be biased. Some research has taken specific account of this possibility. Further research has looked at OECD countries during a period covering the 2008−2009 recession and has revealed that during this period a net number of jobs was always saved by short-time work programs [1], [5], [6]. However, it has been estimated that these effects were temporary, and that by the end of 2010 the net effect of short-time work on employment was negligible or could even have become negative [6]. The negative employment impact of short-time work may have arisen because short-time work dampened the reallocation of jobs toward the most productive firms.

It has been found that a one percentage point increase in short-time work compensation take-up rates is associated with a decrease of one percentage point in unemployment and an increase of one percentage point in employment [1]. The overall effect being that the schemes stabilized employment and reduced unemployment during the 2008−2009 recession.

Again, the evidence suggests that the schemes had a positive impact on permanent employment, but not on temporary employment. This suggests that short-time work compensation is mainly beneficial to permanent workers, as discovered in further research from 2011 [4]. This is perhaps not a surprising outcome, since the schemes are designed primarily to preserve permanent jobs.

Several empirical studies use company-level rather than national-level data to compare employment patterns in companies that use short-time work compensation and those that do not. Again, they find beneficial effects for permanent workers. Research focused on Kurzarbeit, the well-known and long-standing short-time work compensation program in Germany, reveals that companies using Kurzarbeit make less use of temporary contracts, such as temporary agency work, freelancers, and part-time workers, than companies that do not use the scheme [7].

Several studies have also drawn on panel data which cover approximately 1% of all companies and 7% of employees in Germany. Some studies find positive employment effects of short-time work [5], [8] while others find no effects [9], [10]. The results depend heavily on the method used to correct for selection of companies into short-time work, with no obvious lesson to be learned. These studies analyze the impact of short-time work on employment by running regressions where employment growth is explained by short-time work use and by a set of control variables including the revenue growth of the firm. To avoid bias induced by selection of companies into short-time work, they use the prior experience of firms with the program when trying to instrument short-time work. This is questionable, since empirical evidence shows that firms which use short-time work tend to adjust employment more strongly when output falls than firms which do not use short-time work. This behavior of short-time work users may result from technical constraints: firms have more incentives to use short-time work or to find productive activities for incumbent employees when demand drops. Hence, it is not surprising to see no positive effects of short-time work on employment if the selection of firms into the program is not properly accounted for. Instrumenting program use with prior experience does not fully solve this selection issue.

This being said, the most favorable results about employment effects have found that Kurzarbeit in Germany saved about 400,000 jobs, which amounts to about 85% of the full-time equivalent of the short-time work [5]. These findings need to be approached with caution, since they set a 95% confidence interval, which corresponds to a range of between 34,000 and 770,000 jobs saved. Moreover, they might be plagued with significant bias due to the selection of firms into short-time work.

The effect of the schemes on unemployment insurance

Short-time work compensation is typically intended to prevent “excess layoffs,” or in other words to reduce the amount of unemployment, and as shown above, the schemes appear to have this effect. But what effect do these and other schemes have on the costs of unemployment benefit?

If employers have no incentive to “internalize the social cost of their decisions,” or put differently, if they do not have to pay to fire employees, then they will tend to make redundancies if they have too much labor available [1]. This is particularly true when there is an unemployment benefit scheme which provides payments only to full-time unemployed workers. In most countries, employers make social contributions: that is, they contribute to the fund that covers the cost of unemployment benefits.

The immediate cost of redundancy compensation clearly has an effect on employers’ decisions about redundancies, but there is also a method by which social contribution levels might have an effect in the longer term. Experience-rating systems mean that employers’ social contributions are varied depending on their employment pattern, and are increased for the future when they make employees redundant. Just as making a claim on a car or household insurance policy tends to mean that renewal costs are higher, so an employer whose redundant employees make heavy claims on the public purse can be required in this way to contribute more to it.

Research into the impact of experience-rating systems concludes that these systems have the effect (as they intend) of reducing layoffs [11], [12]. In theory, if there is full experience rating, which means that each company fully covers the social costs of its decision to make staff redundant, there will be no excess layoffs.

However, experience rating also has its drawbacks. Many companies, especially small ones, cannot afford the full social cost of making employees redundant. This is particularly true if they need to borrow money to meet the cost, and have limited access to financial markets. Faced with these costs after a downturn in demand they might go out of business, and this will have a negative effect on the economy as a whole.

For these reasons, full experience rating is unlikely to be the optimal solution from an economic perspective, and the state will always need to cover some of the costs of redundancy. This means that there will always be some excess layoffs. In these circumstances, it can be efficient to combine short-time work compensation with unemployment benefits, because the cost to the public purse of the work compensation scheme is offset against the cost saved through the lower claims on unemployment benefit [1].

The effect on job creation and temporary contracts

Despite its potential benefits, short-time work may not be a panacea [13]. In fact, the same problem which plagues unemployment insurance, that is, excess layoffs in the case of partially experience-rated systems, also creates distortions under short-time work arrangements: short-time insurance schemes can bias downwards and hence incorrectly lower the average number of hours worked because they subsidize reductions in working time. They induce inefficient reductions in working time in the absence of incentives that would limit their recourse [1].

In addition, short-time work compensation may hinder job reallocation. That is, people might continue to work in a job for which there is insufficient demand, when in an efficient market they would move to a job for which greater demand exists.

Just as experience rating can be used to regulate employers’ use of redundancies, so it can be used for short-time work compensation schemes. In other words, the employers (and in some cases employees too) who make use of such schemes are required to contribute to the costs over the longer term. This can provide an adequate incentive to limit the use of the scheme, to those cases when the downturn and short-time working is genuinely expected to be temporary.

However the same problem applies to full experience rating in this context: many companies could not afford it, and the cost could drive some out of business. Fixing on the precise optimal combination of schemes and payment for them is difficult or impossible, because so many elements are involved. They include the preferences of workers, the organization of companies, labor market institutions, and the functioning of markets.

So if short-time work compensation is used extensively, there are clear drawbacks. It could result in too many employees working short-time, bar potential new workers from being employed, and hinder adjustments to changed economic conditions. Even when the right solution is to adjust hours rather than to make excess employees redundant, there could be other ways of achieving this, such as plant-level bargaining over hours, wages, and employment, which are more effective [1].

Short-time work compensation schemes and job protection

Short-time working schemes differ greatly from country to country in many aspects. These include the eligibility criteria, the cost to the employers, and the level of replacement income provided. Take-up rates for the schemes are strongly affected by how generous the schemes are to employers (in other words, what proportion of the subsidy to income is provided by the employer and what proportion by the state), and are affected too by the schemes’ generosity to employees (who might reject the reduction in hours and choose redundancy or seek another job if the scheme offers too little) [5].

Employers have a greater incentive to support short-time work compensation schemes when it is expensive for them to make staff redundant. From the employee perspective, the schemes are most attractive to insiders: that is, permanent workers in steady employment, who might prefer to go on the scheme rather than to fight to retain their existing hours, or look for another job. Understandably they are less popular among those who do not qualify for the schemes, for example because they are self-employed, unemployed, or employed on a casual basis.

Short-time work compensation schemes tend to be more developed in countries with stricter employment protection rules and more generous unemployment benefits. They are less developed in countries where the labor market mechanisms make it relatively easy to bargain over wages and hours at the plant level [1], [5]. In particular, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Luxemburg, and Turkey use a combination of strict employment protection legislation and generous short-time work compensation schemes, as is shown in the Illustration.

The positive relation between short-time work compensation schemes and job protection suggests that the cross-country differences in short-time work compensation do not only reflect different ways in which equilibrium is reached in a complex job market. They might also reflect the power in different countries of insiders: that is, people who are already in secure, protected employment [1].

Short-time work compensation schemes do not benefit all workers. Those without a secure, protected job—outsiders, in other words—not only fail to benefit from such a scheme, they might indeed suffer from its introduction. The more secure permanent work is protected, the more difficult it is for outsiders to access this, or indeed any, work. If permanent workers have an easy opportunity to keep their jobs in downturns, and increase their hours when the economy improves, this reduces the chances for others to claim work once it becomes available.

These schemes make forms of temporary and agency working to handle upturns in demand less attractive to employers. Thus they could lead not only to more secure and continuing employment for the favored insiders, but also to a more entrenched core of unemployed or insecurely employed individuals, who continue to be a burden on the public purse. As a result, a high take-up rate does not necessarily imply that the scheme is cost-effective from the point of view of the state [1].

Limitations and gaps

Much remains unknown about the impact of short-time work compensation on employment. While macroeconomic evaluations have identified a net global impact, their conclusions are drawn from a relatively small set of observations. This limits the ability to finely identify the impact of programs, which are very different across countries. Larger sets of observations collected at the company level, combined with relevant empirical strategies, are needed to confirm and fine-tune these conclusions. Taken together, empirical studies relying on firm data do not yet provide clear-cut results.

Very little is also known from a theoretical point of view. Although it is clear that it can be optimal to include short-time work compensation in unemployment insurance systems [1], much remains to be done not only on when short-time work compensation should be used but also on the eligibility criteria, the cost to employers, and the replacement income provided to workers.

Summary and policy advice

All in all, from the scant available empirical evidence, it cannot be excluded that short-time work compensation programs used in downturns have had significant beneficial effects on permanent employment (avoiding job losses and limiting unemployment). From this perspective, it can be worth using these programs during recessions. However, special attention should be devoted to their design. They can lead to inefficiency, both over working hours and in the reallocation of workers to more productive jobs. In order to limit these negative effects, two features should be built into their design.

First, it is worth introducing experience rating, so that employers who use such schemes, and those who use them for longer, pay more toward them. Second, it is important to commit to stable rules, which are best designed under normal economic conditions—and not during recessions—to avoid pressure to set up excessively generous schemes during turbulent periods, since they can be difficult to turn off later. Indeed, persistently high take-up rates can be costly for society as a whole and detrimental to non-eligible workers.

The demand for short-time work compensation is very much affected by employment protection legislation and the centralization of wage bargaining. Factors such as these mean it is more suitable in some countries than in others.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article talks about the problems of selection bias influencing the outcomes of short-time work compensation studies and introduces new “Key references” [8], [9], [10].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Pierre Cahuc