Elevator pitch

Public works programs in developing countries can reduce poverty in the long term and help low-skilled workers cope with economic shocks in the short term. But success depends on a scheme’s design and implementation. Key design factors are: properly identifying the target population; selecting the right wage; and establishing efficient implementation institutions. In practice, rationing, corruption, mismanagement, and other implementation flaws often limit the effectiveness of public works programs.

Key findings

Pros

Public works programs provide a safety net for households after economic shocks.

Programs can be adapted to a variety of country contexts and to both aggregate and idiosyncratic shocks.

Public works programs allow households to self-select into employment when they need it.

Programs can be flexible and decentralized.

Despite implementation problems, public works programs typically reach the target population.

Cons

Rationing, corruption, mismanagement, and other implementation problems limit the effectiveness of public works programs in providing employment at specified wages.

Job-rationing and low-income gains may dampen the impact of public works programs on poverty.

Public works programs can reduce the availability of private-sector jobs.

Governments do not always set clear policy goals and instill them into program design and implementation.

Author's main message

Public works programs have the potential to be important policy tools for reducing poverty, if governments set clear goals and instill them into program design and implementation. But while the safety nets provided by such programs often improve the quality of poor people’s lives, many schemes suffer from implementation problems that limit the welfare benefits for the poor. In practice, such programs are unlikely to have a large and lasting impact on poverty.

Motivation

Large-scale unemployment and underemployment are widespread in developing countries. Job opportunities are especially scarce during the agricultural off-season and in bad economic times, and credit and insurance markets are not developed enough to help households cope with income fluctuations. In these contexts of market failures, public works programs promise substantial benefits in reducing poverty. Governments can step in and directly provide employment opportunities in construction and infrastructure projects, boosting household income and often providing a safety net in times of economic shock.

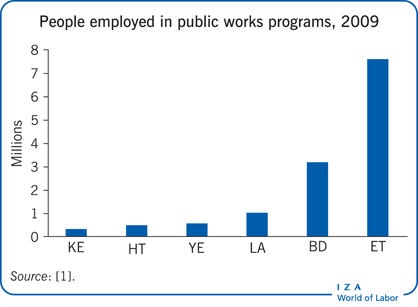

These promised benefits have made public works programs a popular policy tool in developing countries for several decades, but particularly in the last 10–15 years. As the Illustration shows for a selected number of countries for which consistent data are available, developing countries around the world implement such programs, although their size varies substantially. Whereas many older programs were temporary and tried to address short-term unemployment, several newer initiatives have been large and have focused on creating longer-lasting schemes that offer a safety net and predictable longer-term support for poor households. This has broadened the goals of public works programs beyond mitigating aggregate and idiosyncratic shocks to reducing long-term poverty. A few initiatives also aim to provide a bridge to permanent employment, but this is rarely an explicit goal in government schemes in developing countries. The programs are thus seen as a flexible government tool in the fight against poverty that can be adapted to very different country experiences and unexpected challenges.

Public works programs have potential advantages and drawbacks as antipoverty initiatives in developing countries, but the evidence on their effectiveness is weak.

Discussion of pros and cons

The expected benefits of public works programs

Public works programs, properly conceived, promise to be an important policy tool in fighting poverty in developing countries. Their aim is to generate employment for the poor, although program design varies with the country’s situation and specific goals. Some programs are intended to help households deal with aggregate shocks that affect large segments of the population, such as macroeconomic shocks, natural disasters, and seasonal shocks. Others are aimed at reducing long-term poverty or helping households cope with idiosyncratic shocks.

In general, program participation has two benefits for poor households: transfer benefits and stabilization benefits. Transfer benefits are the direct monetary gains from program participation: the wages received for a day’s work minus the costs incurred, including transport costs and forgone income from private-sector jobs not taken. If the program wage is high and the cost of participation is low—for example, because program jobs are local and have little adverse impact on the private sector—the program may boost household income for the poor [2].

Public works programs that operate throughout the year or during times of high unemployment or underemployment can also provide stabilization benefits. During the agricultural off-season or in economic downturns, for example, households may have few employment opportunities in the private sector. Having a public works job helps households avoid large income and consumption fluctuations. If public works programs are long-standing, they also help reduce uncertainty about future household income and may allow workers to make larger investments because people know that they have access to a safety net during bad economic times.

The government has less need in the case of public works programs than in other types of transfer programs to maintain administrative lists of poor households. Because of the nature of public works employment, poor households often either self-select into the program or have a say in the selection of program beneficiaries in other ways. This reduces implementation complexity in reaching the intended population and could make public works programs less prone to corruption, since pretending to be poor to receive government benefits is less attractive than under traditional cash transfer schemes.

Implementation can be decentralized to local institutions, which might have a better knowledge of local conditions, be more flexible in handling projects, and be more transparent, thus curbing opportunities for mismanagement and corruption at higher levels of government. And schemes that can be adapted quickly to newly arising situations and unexpected shocks have the potential to reach the poor more quickly. Projects can also advance local development by creating assets and infrastructure directly where it is needed. Longer-run programs allow government institutions at different levels to learn from past mistakes and to improve upon implementation quality over time.

Finally, if large enough to influence jobs and wages in the private sector, public works programs can help enforce minimum wage laws and raise market wages. The poverty-reducing impact of such initiatives may therefore be substantially larger than those of schemes that simply transfer money to the poor, and may even benefit households that are not direct program participants. Depending on the program features, individuals may also benefit from program participation through training opportunities that improve their chances of finding employment in the future.

The expected costs of public works programs

Public works programs also have drawbacks. If these drawbacks are severe enough, it may mean that the money spent running the program would be more efficiently used reducing poverty in a different way—for example, in a traditional cash transfer program or through improvements in education and health services [2].

Large, ambitious programs may strain government institutions, since the planning and execution of public works programs require more administrative involvement than do other transfer schemes. Institutions may be understaffed, lack the expertise to develop useful projects for local development, and struggle with forecasting demand. These challenges often lead to a rationing of projects, substantially reducing their effectiveness in advancing local development. In the worst case, gaps in technical knowledge may even exacerbate local conditions—for example, where extensive well building or deforestation leads to soil erosion. Institutional constraints may also delay wage payments, undermining the insurance function of the program, and lower the benefits from offering training opportunities. In the context of many rural areas where non-skilled labor in the agricultural sector is the dominant occupation, many training programs will be ineffective unless they are tailored carefully to the specific context and take into account local job opportunities and workers’ financial situations.

In addition, it may be difficult to coordinate players at different tiers of government and, as is often the case in low-income countries, the preferences of donor countries and organizations. This is especially important for longer-run programs that have to secure continued funding despite potential changes in the amount or source of development aid.

Wage-setting is a delicate task. If the program wage is set too high relative to market wages, the program will put upward pressure on private-sector wages for unskilled workers, reducing the number of private-sector jobs. Wages that are too high will also attract workers who are not poor, diluting the program’s antipoverty effects and neutralizing the self-selection benefits. This will be even stronger if public employment needs to be rationed because of high demand for public works jobs [2]. The availability of a safety net may induce excessive risk-taking among workers, since they know that they have access to employment opportunities if their investments do not pay off.

Public works programs are not immune to corruption and mismanagement. Projects may be hijacked by private-sector stakeholders, draining benefits from the rest of the local population. Private employers may try to weaken the program in order to limit any effects on local labor markets. Government officials may exaggerate employment numbers and underpay workers, misappropriating the resources for themselves. Long-standing schemes may be especially prone to these problems, since different parties have time to learn about program loopholes and to undermine the implementation process at various stages.

Empirical evidence of the effectiveness of public works programs is mixed

How effective in general are public works programs in developing countries?

Public works programs are popular in many developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. While their design and implementation have varied, several empirical findings are common to many of them.

One of the most common goals of public works programs is mitigating the negative effects of aggregate shocks. While many small, temporary initiatives since the 1980s are in this category, other schemes show the scalability and adaptability of public works programs that emerged in response to specific shocks. In Sri Lanka, a public works program was part of the Emergency Northern Recovery Project in the aftermath of a long civil conflict. Its goal was to provide short-term employment to affected households and to rebuild local infrastructure, farms, and housing. The initial aim of Argentina’s Head of Household (Jefes de Hogar) Program, which operated between 2002 and 2009, was to help unemployed household heads in households with particularly vulnerable family members (such as children, pregnant women, and people with disabilities) ride out the severe financial crisis of 2002. Over time, it developed a stronger focus on training to build human capital and increase long-term employment opportunities.

Public works programs also provided a popular government tool in the aftermath of the 2007–2009 world economic crisis to combat rising unemployment, poverty, and food insecurity. The World Bank funded programs in over 24 countries, and a number of governments in developing countries introduced or scaled up their own projects.

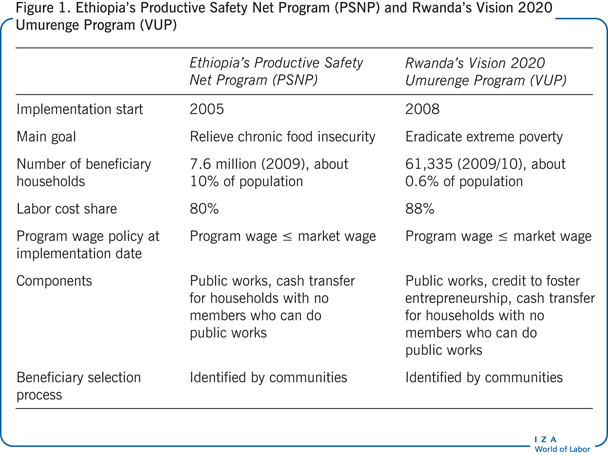

While these are examples of responses to one-off shocks, another goal is to help households cope with the recurring shocks of droughts and food crises. Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program is one such scheme. First implemented in 2005, the donor-funded scheme combines geographic targeting and community involvement to identify particularly vulnerable households. This large program, covering 10% of the population (7.6 million people) in 2009, aims to relieve chronic food insecurity within five years, combining shock mitigation with long-term poverty reduction (Figure 1).

Other programs, like Rwanda’s Vision 2020 Umurenge Program, introduced in 2008, have poverty reduction as their main goal. Vision 2020 aims to eradicate extreme poverty by 2020 through a combination of public works employment and initiatives encouraging entrepreneurship and longer-term employment (Figure 1).

A few programs also focus on other goals, such as providing training opportunities, which are meant to help beneficiaries get more secure and better-paid jobs in the future. But this type of government initiative is relatively uncommon compared with the efforts in many developed countries. The commitment to using public works projects to improve local development, for example by building infrastructure, also usually remains at best a secondary consideration.

Across a diverse set of goals and contexts, empirical analyses typically find that public works programs in developing countries reach their target group of poor households. Although some fraction of the non-poor often benefits as well, targeting seems to be fairly successful in most public works programs and to work better in this respect than a number of traditional cash transfer programs for the poor.

It is important for targeting to get the wage right. The wage level has major effects on the attractiveness and effectiveness of the program. Different countries have opted for very different wage levels. Wages in public works programs in the late 1980s and early 1990s were below the market wage in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Chile, Pakistan, Senegal, and Sri Lanka, but above it in Botswana, India, Kenya, the Philippines, and Tanzania. High-wage programs often attracted more non-poor participants than did low-wage programs, and resorted to rationing because demand for jobs outstripped supply [2], [3]. Data from 2012 show that rationing has been widespread in India’s employment guarantee scheme, especially in poor regions [4].

Some contemporary studies document important transfer benefits for program participants. Working in a public works program rather than in typical private-sector employment is associated with a 25–40% higher wage in Argentina, Colombia, and Peru. Timing seems crucial to creating welfare benefits for the poor. A study from 2011 finds transfer benefits as high as 93% in Liberia, possibly because few other sources of employment were available during the same time period.

Stabilization benefits for program participants can be valuable even when the programs are not implemented perfectly. In two public works programs in India, where rationing reduced estimated transfer benefits, the insurance function remained important because public works employment was available even in economically bad times [5].

Whether high-wage programs have led to increased market wages and negative effects on private-sector job availability has been studied much less thoroughly. High-quality evaluations of public works programs are difficult to achieve because of data limitations, the commonly temporary nature of the programs, and the challenge of setting up comparison groups to analyze how labor markets would have been different without the program. Some older programs were implemented during peak agricultural seasons, which vastly increased the probability of negative labor market effects, especially in programs that also paid an above-market wage, as in Kenya and Tanzania [2]. This is much less common today, when most schemes are rolled out in response to large aggregate shocks or operate mainly during the agricultural off-season.

How effective is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) in India?

One of the few cases in which private-sector effects have been studied in detail is India’s current flagship public works program, the MGNREGS, which was designed as a poverty alleviation tool. Several features of the program are particularly interesting. National legislation guarantees each rural household (or about 70% of India’s population) up to 100 days of public works employment a year at the minimum wage. Annual expenditures on the scheme amount to about 1% of GDP. Participation is supposed to be demand driven, with households self-selecting into employment at any time of the year. Although it is a national program that is mostly paid for by the central government, it is implemented by local governments. Projects are aimed at local development, with a focus on drought-proofing and infrastructure creation.

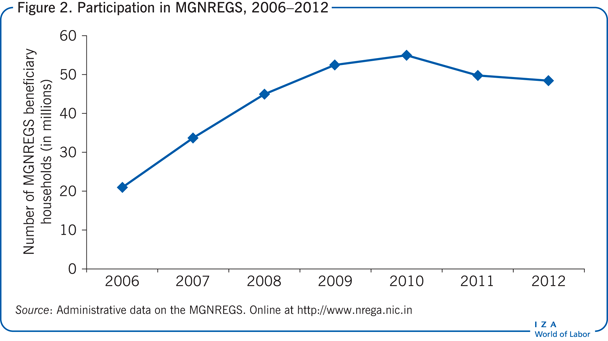

The program is arguably the largest and most ambitious public works program in the world. Figure 2 shows the number of households provided employment according to administrative sources since the introduction of the MGNREGS. In 2011–2012 the scheme benefitted about 50 million households annually.

Implemented in three phases between 2006 and 2008, the program now operates in all rural areas in India. Already one of the longest-lasting public works programs in the world, it is expected to remain in operation for many years. The phasing-in of the program has made it possible to conduct high-quality research on effectiveness (quasi-experimental studies of causality) that is not often possible in other contexts. Areas that already had access to the program could be compared with areas that did not in order to show differences in labor market outcomes with and without the program.

The program wage is equal to the minimum wage, which tends to be higher than the market wage in many parts of India, especially for women. This feature leads to rationing of employment in practice, especially in poorer states. While there is evidence that the program is attractive to some richer households as well as to poor households, it still reaches the most disadvantaged groups [4].

The relatively high wage seems to have led to some crowding out of private-sector employment for men [6], [7], although it is still unclear whether this is a response to higher wages. Some empirical analyses document substantial wage increases for men and especially for women, which is consistent with the idea that the program helps enforce the minimum wage laws in rural areas [6], [8], [9]. Other estimates find almost no wage increases, however [7]. This discrepancy might be explained in terms of the time it takes for the higher wages in the public works program to influence private-sector wages. It might also be a result of political influence on which districts receive the program early, so that the poorest districts are not selected first, which could have different effects on estimates depending on the econometric model specification.

In general, the evidence shows important stabilizing benefits for the program from employment availability during the agricultural off-season and in areas with higher income uncertainty because of volatile weather conditions [6], [7], [10]. This insurance function seems more important than the transfer benefits, since the number of jobs created is relatively modest compared with the size of the national workforce and the number of people desiring employment [4], [7].

In addition to rationing employment, there is growing evidence of other implementation problems that impede effectiveness. Corruption reduces program effectiveness in at least some parts of the country, although not in all. In one Indian state, administrative data substantially overstate employment compared with employment information collected from households directly, and the increase in the minimum wage was not passed through to program workers [11]. In another Indian state, the program was found to be better protected from political pressures [10].

Overall, the employment statistics in Figure 2 are therefore most likely overestimates of the actual number of households provided with jobs. The Indian government has adjusted some elements of the program to reduce opportunities for corruption at the local level, for example by introducing direct bank transfers of wages. Public works projects seem to create few assets and infrastructure in practice, with the bulk of works belonging to drought-proofing and land development categories.

Overall, empirical studies suggest that the Indian public works scheme has had only a small effect on long-term poverty by raising household income, not least because of substantial implementation challenges. It is unclear whether these problems are worse than those of other government programs, however. At the same time, the program has provided an important safety net for poor households, and its negative effects on the private sector appear to be small.

Limitations and gaps

Causal analysis of the labor market effects of public works programs is often challenging because of the need for counterfactual observations of labor market developments—what would have happened in the absence of the program? While this was possible for India’s MGNREGS, the results do not necessarily apply to other contexts or to programs with different institutional and design features. It is also unclear how the benefits and drawbacks of this public works program compare with those of other types of poverty-reduction programs that could be implemented instead.

Additionally, almost all research, including the work on the MGNREGS, focuses on short-term effects because of data limitations and restrictions imposed by the empirical estimation strategy. That means that the long-term effects of public works programs on poverty are not yet well understood. This is important, because it may take some time for local government institutions to learn how to implement the programs and for households to benefit from participation. The long-term effects of public works programs could therefore be larger than suggested by the short-term results. The opposite would be true if private-sector employers or government officials learned over time how to undermine the schemes.

There is also little empirical research on the workings and structure of local labor markets in developing countries, which prevents a better understanding of how likely public works programs are to crowd out private-sector jobs in practice. In the existing literature, it is often unclear whether public works projects really do not negatively affect the availability of jobs in the private sector, or whether this is just a by-product of low implementation quality.

Summary and policy advice

Public works programs are a popular form of government intervention in developing countries. Empirical studies show that these programs can generate important benefits, but they also reveal why it is often difficult in practice to make the programs effective. One challenge is the wage level. There is a trade-off between setting the wage so low that it attracts only very poor people and does not distort local labor markets and setting it high enough that it has a real impact on the income of the poor. In practice, public works programs also tend to suffer from implementation problems such as rationing, corruption, and mismanagement, although overall the targeting of programs to the poor seems to work fairly well. The safety net function of these programs is usually important and can generate welfare gains even when the program functions imperfectly.

When designing and implementing public works programs as part of a poverty alleviation strategy, governments should be very clear about their policy goals and design programs accordingly. Key factors are: identifying and reaching the target population of workers; setting the right wage; and establishing government institutions whose implementation of public works projects is efficient and transparent.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Laura Zimmermann

Features of MGNREGS (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme)

National legislation guarantees each rural household up to 100 days of public works employment a year at the minimum wage.

Participation is supposed to be demand driven, with households self-selecting into employment at any time of the year.

It is a national program that is mostly paid for by the central government, but implemented by local governments.

The projects are aimed at local development, with a focus on drought-proofing and infrastructure creation.

In 2011–2012 the scheme benefitted about 50 million households annually.

Implemented in three phases between 2006 and 2008, the program now operates in all rural areas in India and is expected to remain in operation for many years.

The program wage is equal to the minimum wage, which tends to be higher than the market wage in many parts of India, especially for women.

The program seems attractive to some richer households as well as to poor households, but it still reaches the most disadvantaged groups.