Elevator pitch

A considerable part of the poverty that is measured in a single period is transitory rather than persistent. In most countries, only a portion of people who are currently poor are persistently poor. People who are persistently poor or who cycle into and out of poverty should be the main focus of anti-poverty policies. Understanding the characteristics of the persistently poor, and the circumstances and mechanisms associated with entry into and exit from poverty, can help to inform governments about options to reduce persistent poverty. Differences in poverty persistence across countries can shed additional light on possible sources of poverty persistence.

Key findings

Pros

A considerable part of poverty measured in a single period is transitory rather than persistent.

Distinguishing between temporary and persistent poverty is important as economic policy should focus on preventing persistent poverty.

Understanding characteristics of the persistently poor and events associated with entry and exit into poverty are important for informing anti-poverty policies.

The characteristics of the persistently poor are often different from those of the currently poor.

It is relevant for economic policy to know whether poverty persistence is due to individual characteristics or to poverty-trap mechanisms (being poor today increases the risk of being poor in the future).

Cons

How to weight aspects of poverty persistence such as duration, intensity, and recurrence is unclear.

It is difficult econometrically to separate poverty persistence due to individual characteristics from that due to poverty-trap mechanisms.

Identifying events associated with poverty entry and exit can inform policies, but a large share of entries and exits cannot be clearly characterized in terms of individual events.

There are common factors in poverty persistence across countries but also several differences.

The evidence is mixed on whether incentive problems such as welfare dependency increase the poverty trap effects that can lead to persistent poverty.

Author's main message

Not all people who are poor are persistently poor. Evidence suggests that unemployment, retirement, and single parenthood are closely associated with persistent poverty and that higher education tends to protect against it. There is also evidence of a poverty trap, meaning that policy should aim to prevent people from falling into poverty because once poor, the probability of being poor in the future increases. Policies that promote education, employment, and attachment to work will be most effective in reducing persistent poverty, along with policies that strengthen family and job stability (such as childcare subsidies).

Motivation

Snapshots of who is poor during a particular period (cross-sectional or current poverty) provide an incomplete picture of the prevalence of poverty in a population. Knowing that 10% of the people in a country are poor in a given year leaves open the question of whether poverty for these individuals is a persistent or a transitory phenomenon. For several reasons, the persistent or long-term share of poverty should receive more attention than the transitory share [2].

First, the detrimental effects of persistent poverty on personal welfare are expected to be more severe than those of transitory poverty. Second, extended exposure to poverty can have further injurious consequences, such as the running down of assets, stigmatization, and disruption of personal relationships. Third, extended exposure to poverty can have negative long-term consequences if experienced during the formative years of childhood and adolescence, particularly if persistently low resources preclude investments in human capital and personal development. Fourth, long or recurrent poverty spells mean that the burden of poverty is highly concentrated, with the bulk of total poverty borne by a few people who remain poor rather than a larger number of people who experience shorter spells poverty [2], [3], [4]. These particularly detrimental effects, together with its concentration among a relatively small group of people, should lead policymakers to focus on preventing persistent poverty.

An extensive literature has looked at the extent, composition, and mechanisms behind persistent poverty in different countries. The findings can inform policymakers about the options for economic and social policy and help them devise measures to prevent the temporarily poor from becoming persistently poor.

Discussion of pros and cons

When should poverty be considered persistent?

A person whose income falls below a pre-defined poverty line is usually counted as poor. In European studies, poverty lines tend to be defined relative to average or median income (for example, 50–60% of median income), whereas in US studies poverty lines are often defined as an absolute value (the official US poverty line is based on the cost of a defined basket of food).

While it is relatively easy to define who is poor under these definitions in a given period, it is less easy to define who is poor across multiple periods of time (persistently poor). A straightforward definition counts the number of periods within a fixed period of time that a person’s income or consumption is below the poverty line—for example, the number of years in poverty over a three-year period. A person who is poor during all or a certain number of periods during that time is defined as being persistently poor.

The EU persistent at-risk-of-poverty indicator (part of the portfolio of EU social indicators) considers a person who was poor in a given year and in at least two of the three preceding years to be persistently poor. By this definition, the persistently poor are a sub set of individuals who are currently poor (poor during the conditioning year). This will not necessarily be the case in the more general form of the fixed time spread approach, in which one counts the number of years spent poor without conditioning on being poor in a particular year.

Apart from the ad hoc choice of the length and period of the time spread, an obvious disadvantage of the fixed time spread approach is that it ignores the spell structure of poverty and people’s movements in and out of poverty. For example, considering a fixed time spread of three years ignores the fact that the poverty spells of some individuals may have started before the three-year time spread or continue beyond it. This limitation is particularly severe if the chosen time spread is short.

An alternative way to measure poverty persistence is to focus on the length of spells spent in poverty. However, this measure of poverty persistence ignores the possibility of re-entries into poverty. A person who moves in and out of poverty multiple times should also be considered persistently poor. Thus, a now widely held view of persistent poverty sees it as a sequence of climbing out of poverty and falling back in over time [3].

A disadvantage of definitions based on the number of periods spent below the poverty line or the duration of individual poverty spells is that they do not include information on how far people are from the poverty line. This means that small fluctuations around the poverty line (or fluctuations of the poverty line itself if it is a relative line) may generate spurious counts of entries or exits into poverty. Measurement error can also lead to such fluctuations. Using a binary poverty indicator also means that differences in the severity of poverty are not taken into account, which may be particularly relevant if individuals with short but severe poverty spells are compared with those with long but less severe spells.

An alternative definition of persistent poverty, which partly addresses this limitation, pools incomes over several periods and compares them to a poverty line based on pooled or permanent incomes. This definition incorporates information on the absolute income of each person across periods. It is often used to supplement other definitions based on the count of periods below the poverty line [3], [4], [5]. On the negative side, it assumes full transferability of incomes across periods, which may be especially questionable for low-income individuals.

Finally, a simple and parsimonious approach is to measure only period-to-period transitions in poverty status. For example, poverty is considered to be more persistent if it is more likely for individuals to be poor in the current period if they were already poor in the previous period [6], [7]. This approach is more intuitive and informationally less demanding, but it is obviously also less informative.

Combining the different aspects of poverty persistence such as duration, recurrence, intensity, and transferability across periods into a consistent summary measure of poverty persistence is difficult, though attempts have been made, including ones that add other aspects of poverty such as inequality [8]. In practice, simple measures of persistent poverty such as the number of periods spent poor within a fixed time spread or period-to-period transition probabilities still dominate, most likely because they are easy to understand or because of data limitations.

Evidence on the extent of poverty persistence

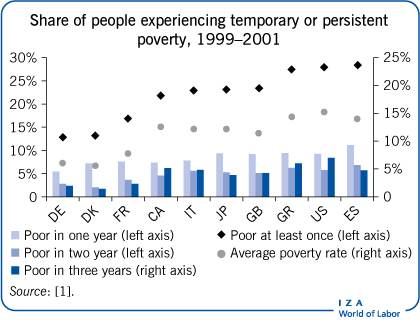

The amount of persistent poverty, as opposed to current or temporary poverty, depends on the definition. For example, if the time period is short (three consecutive years in this case, generally 1999–2001) and the number of years spent below the poverty line is the measure of persistence, then for OECD countries people who have been poor for one year make up about 8% of the population, people poor for two years make up about 4%, and people poor during all three years make up about 5% (with the poverty line defined at 50% of median income) [1]. The average annual poverty rate during the same period was about 10%, illustrating that only a certain proportion of people in poverty are poor for more than one period out of three. This is also reflected in the gap between the percentage of people who are poor at least once in three years (about 17%) and the percentage who are poor in all three years (about 5%).

Similar evidence for EU countries based on different data sources and the official EU persistent at-risk-of-poverty indicator (poor people in a given year who were also poor in at least two of the last three years) suggests a 9% rate of persistent poverty in member states of the EU [9].

As explained, the use of a relatively short time spread can be criticized for ignoring relevant information about poverty experiences outside the chosen time spread. Extending the time spread to 10 years and considering poverty spells that have just begun during that time spread, an influential US study looking at poverty in the 1980s and earlier found that about 30% of people who had just begun a poverty spell spent only one year in poverty out of the next 10, about 15% spent two years, and about 12% spent three years [3]. About 35% of people beginning a fresh poverty spell were poor for five years or more out of the next 10, which could be defined as the subpopulation of the persistently poor.

A similar study using British data for the period 1991–2006 found that about 20% of people starting a fresh spell of poverty spent only one year out of the next 10 below the poverty line, about 16% spent two years, 12% three years, and almost 44% spent five years or more [4].

A comparable study for Germany using data for the 1990s and early 2000s estimated that 45% of people who had just begun a poverty spell spent only one year in poverty out of the next 10, 18% spent two years, 12% spent three years, and only 16% spent five years or more [2]. However, this small group of 16% bore about 43% of the overall burden of poverty measured in person-years. The study also showed that about one-third of people who were currently poor were poor in five or more years out of the next 10, and one-third were in the midst of a poverty spell of five years or more.

Although it is clear that persistent poverty is by definition lower than current (cross-sectional) poverty, how the two are related is an interesting question. There is evidence that countries with high current poverty rates also have high rates of persistent poverty [1], [10]. Independent of the empirical form of the relationship, its existence is not surprising since current poverty rates are the result of poverty entries and exits, which in turn are related to the rate of persistent poverty. Under plausible assumptions, this may lead to a near-linear relationship between current and persistent poverty whose slope depends on the entry and exit rates [10].

Mechanisms of poverty persistence

What mechanisms can explain why some people experience poverty in a permanent or recurrent way? The most obvious explanation would be that people who are persistently or recurrently poor have durable characteristics that make them prone to poverty in a given period. These might be observed characteristics, such as low educational qualifications, lack of employment, health problems, and difficult living arrangements, or more typically unobserved characteristics, such as low motivation, lack of skills, and generally unfavorable attitudes.

An alternative mechanism of poverty persistence is state dependent: being poor in one period directly increases the likelihood of being poor in a future period (known as the poverty trap or state dependence). In this situation, there is a direct dynamic effect from being poor today to being poor in the future. This effect could occur because of an incentive mechanism (the loss of entitlement to welfare payments means that it is not worthwhile to take a job) or because slipping into poverty triggers processes that make future poverty more likely, such as demoralization, habituation, stigmatization, and depreciation of human capital. There is evidence that being poor in one period decreases the likelihood of being employed and of living with a partner in the next period, potentially giving rise to dynamic poverty effects [7]. What these mechanisms have in common is that individuals who are poor in a given period have a tendency to become accustomed to or to get stuck in their situation.

It is hard to distinguish empirically between poverty persistence that is due to enduring unobserved characteristics and that due to causal poverty trap mechanisms. It may look as if past poverty is causally associated with future poverty, but this relationship may be due to persistent unobserved background characteristics, such as bad health or low motivation, that increase the likelihood of being poor in each period.

Several studies have presented empirical evidence for a poverty trap mechanism. A typical finding is that around half of poverty persistence across periods is due to state dependence (the likelihood of being poor in one period depends on the poverty state of the previous period) and around half to observed and unobserved individual characteristics [6], [7].

There is less evidence for a poverty trap mechanism operating through welfare dependency than there is for a more generally defined poverty persistence in terms of low income. For example, a study for Germany found little evidence for state dependence in welfare dependency [11]. This suggests that incentive problems are not the only mechanisms behind poverty trap dynamics. On the other hand, there is evidence for Canada suggesting that poverty trap effects are higher in provinces with more generous welfare levels [12].

A more general way to describe the relationship between current and past poverty is to define the likelihood of exiting poverty as a function of the time already spent in poverty. There is evidence that the likelihood of exiting poverty decreases the longer a person has been poor, even after controlling for unfavorable background characteristics [2], [3], [4]. In this case, the risk of being poor is said to be duration dependent. Poverty duration dependence may be rooted in the same processes as poverty state dependence: gradual demoralization, habituation, and depreciation of human capital.

The finding that being poor in one period increases the likelihood of remaining poor in the next period does not contradict the claim that only a certain proportion of the currently poor are also persistently poor. The evidence does not say that once poor, a person will always stay poor. It says only that among people who are currently poor, a larger fraction will also be poor in the next period than among a group of people who are not currently poor but with otherwise comparable observed and unobserved characteristics.

If poverty state dependence or poverty duration dependence exist, that has important implications for policy. The aim of policy should then be to prevent people from falling into poverty in the first place because once poor, the probability of being poor in the future increases. Such policies will be more effective because they will reduce not only current poverty but also future poverty.

Characteristics of the persistently poor

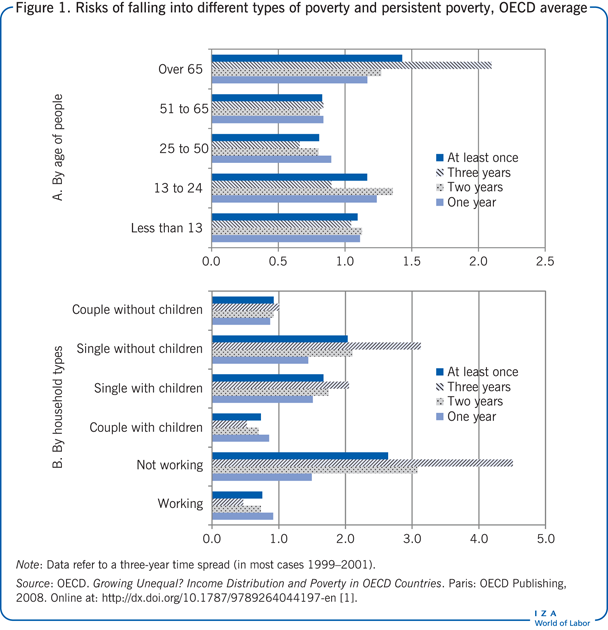

What kind of personal and household characteristics make individuals particularly susceptible to persistent poverty? A common finding across many countries is that being retired, living in a household in which no one is employed, or living in certain types of household (such as single-parent households) significantly increases the likelihood of being persistently poor (Figure 1) [1], [5], [13]. There is also evidence for Italy and the US that female-headed households tend to have a higher risk of persistent poverty, though not for Germany [2], [3], [4]. In most countries, a high level of education has been found to considerably reduce the risk of persistent poverty [2], [3], [4], [5], [13].

A potentially policy-relevant finding is that the population of the currently poor can be quite distinct from that of the persistently poor. For example, evidence for Germany shows that the main risk factors for current poverty were unemployment, having many children, and unfavorable household type (especially single parenthood), while the main risk factors for persistent poverty were old age (largely because of fixed incomes) and economic inactivity [2]. Groups with a high risk of being poor in a particular period were not unduly likely to suffer from persistent poverty, implying that many of the risks for current poverty were temporary (unemployment, lone parenthood). Similarly, pensioners faced below-average risks of cross-sectional poverty but were considerably overrepresented among the persistently poor.

Alongside easily observable characteristics such as household structure, education level, employment behavior, and age, there remains considerable scope for persistent unobserved characteristics that increase the risk of persistent poverty. For example, studies for Germany, the UK, and the US have shown that there is typically a small group of people whose unobserved characteristics (such as motivation, skill levels, and attitudes) lead to very low poverty exit rates and relatively high re-entry rates [2], [3], [4].

Events associated with poverty entry and exit

In addition to knowing what characteristics are correlated with chronic poverty, knowing what kind of events are typically associated with poverty entries and exits is important for understanding poverty dynamics. These could be changes in family structure (divorce, marriage, birth of a child, formation of a new household), labor market-related changes (number of workers in the household, unemployment), and major changes in income components (capital income, labor income, and public transfers), although it is not always possible to strictly separate the different types of events.

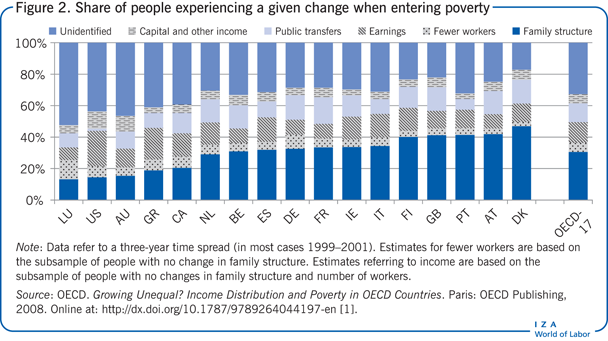

Evidence for OECD countries suggests that entry into poverty is frequently associated with changes in household structure (20–40% of all entries), followed a distant second by changes in the number of workers in the household, conditional on there being no changes in household structure (5–15%; Figure 2) [1]. Finally, again conditional on no changes in family structure or the number of workers, around 30% of poverty entries are related to major declines in particular sources of income, particularly drops in public transfers (except for the US, where declines in labor income are more important than changes in public transfers) [1].

However, a substantial share of entries into poverty (20–50%) cannot be accounted for by these factors individually because either more than one kind of event was associated with the entry into poverty or because the poverty entry was the result of a relatively minor income change (meaning that the household was already not far from the poverty line) [1].

More detailed cross-country comparisons for Canada, Germany, the UK, and the US have yielded similar patterns and also found a similar ranking of possible events associated with poverty exits [5]. The events most often associated with poverty exits are changes in household structure, followed by major increases in income components and an increase in the number of full-time workers in the household [5]. Moreover, in Germany and the UK, a large share of exits from poverty are related to increases in government transfers; that was much less common for Canada and the US [5].

Cross-country differences in poverty dynamics

Cross-country comparisons reveal additional lessons on the dynamics of poverty. Comparisons of persistent poverty measures based on market income (before government interventions) and disposable income (after government interventions) suggest that the risk of persistent poverty is halved by the tax and transfer system in Germany and the UK, but is only moderately or marginally changed in Canada and the US, where labor market success and employment status more strongly affect the relationship between current and persistent poverty [5]. Cross-country evidence also suggests that the risk of persistent poverty tends to be higher and more concentrated in Canada and the US than in Germany and the UK [5]. There is also evidence that among European countries, social democratic-leaning countries (Denmark, the Netherlands) have somewhat lower risks of persistent poverty than countries with corporatist leanings (Belgium, France, Germany), which in turn have much lower risks than southern European countries (Italy, Greece, Portugal, Spain) and countries with liberal leanings (Ireland, UK) [13].

There is also some evidence that high initial exit rates from poverty in countries with social democratic and corporatist governments decline quickly with poverty duration, whereas exit rates tend to remain high with the duration of poverty in some liberal and southern European countries. This suggests the existence of incentive problems in the first group of countries [13]. Apart from these differences, which are often just differences in levels, it is remarkable that both the patterns of entries and exits and the correlates of persistent poverty are shared across a large number of countries [13].

Limitations and gaps

While some of the studies cited here use data and time periods well-suited to cross-country comparisons, perfect comparability across countries is unrealistic. In addition, differences in such features as the state of the business cycle and the years chosen for analysis may limit the validity of such comparisons. The studies cited here cover specific time periods, some of which are more recent than others. Some use data up the middle of the first decade of the 2000s [4], [7], [9], [10], [11]; others use data from the 1990s or early 2000s [1], [2], [5], [6], [8], [12], [13] or even from the 1980s or earlier [3].

Although data collection has improved in many countries, cross-nationally comparable data sets either do not exist for large sets of countries, or they permit only restricted analyses of poverty dynamics across longer time periods, which make updating cross-country analyses of poverty persistence a challenge. For example, the cross-nationally comparable European Community Household Panel, used in several studies [1], [5], [8], [13], has been replaced by the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, which features only a four-year rotating panel structure, thus severely restricting the possibility of analyzing longer-term poverty dynamics [10]. Nonetheless, considering that the evidence on poverty persistence and poverty dynamics shows so many common patterns across different time periods, countries, and institutional regimes, it seems unlikely that using newer data will completely alter the findings.

Summary and policy advice

The evidence on the persistence and dynamics of poverty suggests that only some of the currently poor are persistently poor. The share of the persistently poor tends to be higher in countries where the rate of current poverty is high. Several factors have been found to be related to a higher risk of persistent poverty. One is the enduring observed and unobserved personal characteristics that make some individuals more poverty-prone. Another is the poverty trap: being poor in one period may increase the risk of remaining poor in subsequent periods because of incentive problems or because experiencing poverty leads to demoralization, stigmatization, habituation, or depreciation of human capital.

Evidence suggests that the characteristics most closely associated with persistent poverty are unemployment, retirement, and unfavorable household structure. Working in the opposite direction to shield people from persistent poverty in many countries is a high level of education.

Several factors have been found to be related to poverty entry and exit: changes in household structure, substantial increases or decreases in labor income or government transfers, and, to a lesser extent, changes in the number of workers in the household. However, a considerable share of cycling into and out of poverty cannot be accounted for by these factors, either because more than one type of event is associated with the poverty transition or because the transition is not associated with the observation of a substantive event.

From a broader policy perspective, these findings suggest that economic policies aiming at promoting education, employment, and attachment to work will be most effective in reducing the risks of persistent poverty. Risks that are related to family structures may be more difficult to influence, but policies strengthening family stability or facilitating the balance of commitments to home and work (such as childcare subsidies) can reduce the risk of persistent poverty. The finding that pensioners, whose income sources are largely fixed, are generally overrepresented among people who are persistently poor makes a case for policies to improve the welfare of this group. Because some older people may have accumulated considerable wealth that can be income-producing, such old-age policies should be means-tested.

The evidence that being poor in one period causes an increase in the risk of being poor in future periods suggests that preventing people from becoming poor in the first place will also help to reduce persistent poverty.

Finally, the evidence suggests that European social welfare states are more successful in lowering the number of the persistently poor than are Canada and the US, where labor market success and employment status more strongly affect the relationship between current and persistent poverty.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Martin Biewen