Elevator pitch

Evidence shows that many college graduates are employed in jobs for which a degree is not required (overeducation), and in which the skills they learned in college are not being fully utilized (overskilling). Policymakers should be particularly concerned about widespread overskilling, which is likely to be harmful to both the welfare of employees and the interests of employers as both overeducation and overskilling can lead to frustration, lower wages, and higher quitting rates while also being a waste of government money spent on education.

Key findings

Pros

Many college graduates are employed in jobs that neither require a degree nor make full use of skills learned in college.

Empirical analyses based on cross-section data suggest that overeducation is a sign of market failure.

Empirical studies using cross-section data find a significant wage penalty and a reduction in job satisfaction for overeducated workers.

Studies using panel data indicate that the combination of overeducation and overskilling is most damaging to employees’ outcomes.

Cons

If overeducation is an investment in future earning power, mismatches are temporary and require no policy intervention.

Some people choose to work in jobs for which they are overeducated because they offer other non-financial benefits.

Panel data suggest no wage penalty for being overeducated or overskilled, and only a small penalty for those who are both, at least for men.

Overeducated workers find it easier to change jobs than overskilled workers or workers whose jobs and education are well matched.

Author's main message

Labor market mismatches (where employee qualifications do not match job requirements or are not used on the job) can result from overeducation or overskilling, which are two distinct phenomena. Policymakers should be especially concerned with overskilling which is likely to be harmful both to the welfare of employees (lower job satisfaction) and the interests of employers (lower productivity). Thus policy should ensure that education policies recognize that they must integrate with policies on skill formation outside the workplace, in case over-production of formal education interacts negatively with skill formation.

Motivation

The share of the workforce with a higher education is increasing in many countries. This trend necessitates large investments in time and resources by students as well as substantial government support. Yet there is evidence that many graduates are employed in jobs that do not require a college degree, and in which the skills obtained in college are not being fully utilized. What does this mismatch say about the supply and demand of graduates?

There are many reasons why the supply of and demand for graduates might not match in a dynamic labor market. For example, jobs that previously required college education may be at risk of replacement by advanced automation techniques. In that case, understanding the extent of and potential impacts due to mismatch in the labor market is a crucial question when designing both education and labor policies.

Discussion of pros and cons

Understanding differences: The importance of getting the appropriate data

Most of the literature on education or skill mismatches that has found significant negative associations between wages and job satisfaction and mismatches is based on cross-section data, which provide information at just one point in time. However, this type of data cannot provide reliable estimates on whether mismatch is causing lower wages and lower job satisfaction or is simply associated with them.

It is important to know about education and skill mismatches, job dynamics, and their causal relationship to wages, job satisfaction, and job mobility. Investigating such relationships requires the use of panel data, which consist of repeated observations for the same individuals over time and control for all unobserved individual differences that remain constant over time. Such differences include measures of ability, personality, and other such important indicators of labor market success. Without controlling for this type of variation, a negative association between mismatch and wages could be due either to mismatch in itself harming productivity and wage prospects or due to the presence of an unobserved individual factor (e.g. low ability) which makes mismatch and lower wages more probable. Panel data estimation “controls” for this heterogeneity by measuring directly the impact of either becoming mismatched or becoming well-matched for each individual who changes mismatch status (e.g. by switching from a well-matched job to a job where they face mismatch) on their observed change in wages, job satisfaction, and other such labor market outcomes. This means the estimated relationship will be that of how becoming mismatched causes in itself a drop in wages or job satisfaction.

Further, panel data can reveal whether mismatches are temporary or permanent and can shed light on whether any negative repercussions of mismatches encountered early in a working life are reversible later through training or experience. Unfortunately, the lack of panel data has hampered attempts to elucidate such issues. An exception, explored in this article, is a series of recent studies based on panel estimation of graduate mismatch using the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey [1], [2]. This survey includes a question on skill mismatch and provides sufficient data on graduate qualifications and employment to estimate overeducation and account for unobservables, such as ability or preferences.

Overeducation and overskilling

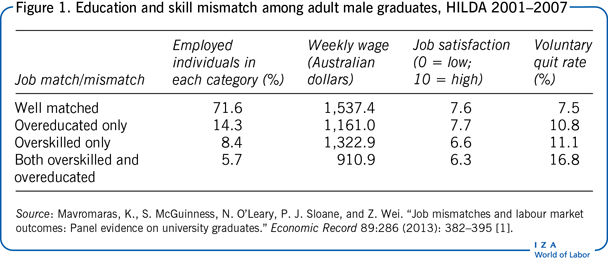

Overeducation and overskilling are distinct phenomena, as indicated by their low correlation when in the HILDA data. A novel feature of new work based on this data is the categorization of graduates into four mutually exclusive groups: (i) well matched in both education and skills; (ii) overeducated only; (iii) overskilled only; and (iv) both overeducated and overskilled [1], [2]. This categorization proves to be very illuminating when the effects on wages, job satisfaction, and job mobility are compared. As can be seen in Figure 1, 28.4% of the sample are mismatched; this group earns less than matched workers and has lower job satisfaction if overskilled as well as a higher voluntary quit rate overall. Above all, the results suggest that, at least at a descriptive level, it is a combination of overeducation and overskilling, rather than either one individually, that has the most damaging outcomes.

Evidence from panel data analysis

As mentioned earlier, panel data estimation has distinct advantages over cross-section analysis for examining the impacts of job mismatch over time. Studies based on panel data cast doubt on the results of cross-sectional analyses, which have dominated the literature. Analysis of the Australian panel data shows that the relationship between job mismatch and labor market outcomes is strongly influenced by unobserved individual differences [1], [2]. Although the data cover only a group of male graduates in a single country, there is reason to believe that the data are not atypical.

For economy of space, the following analysis is limited largely to men. While the mismatch pattern is similar for women, the negative wage and job satisfaction effects are stronger for women than for men, which suggests that mismatch is even more damaging for women. The results below are highlighted less for the findings themselves and more as illustrations of how to address shortcomings in the literature and emphasize important elements of the analysis.

To allow for comparisons with the earlier literature, a so-called pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) model was used to estimate the wage effects of mismatch as a benchmark. Pooling across waves enables a direct comparison to be made with cross-section studies. For job satisfaction and job mobility, which involve binary variables, a so-called pooled probit model was estimated as a benchmark. For dealing with unobserved individual variation, a so-called random effects probit model with a Mundlak correction was estimated.

Mismatch and reduction in wages

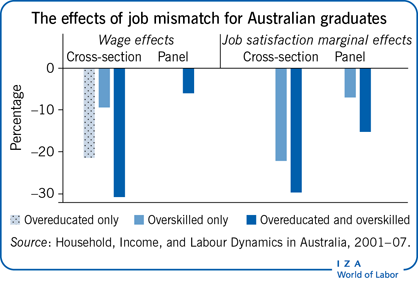

Studies with cross-section data for male college graduates who are overeducated only or overskilled only often find negative effects on wages. However, controlling for unobserved individual differences removes most of these negative wage impacts. Panel regression results thus reveal that it is only male graduates who change from a well-matched job to one for which they are both overeducated and overskilled that suffer a wage penalty (of just under 6%).

Impact of job mismatch on job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is treated as another outcome of mismatch by observing the impact that each type of mismatch has on the level of satisfaction after controlling for other factors that might influence satisfaction. Where a mismatch does not reduce job satisfaction, it is likely that the mismatch reflects a voluntary underutilization of qualifications or skills.

Empirical results show that being overeducated on its own has no discernable effect on job satisfaction among the HILDA sample. (A similar result was obtained for the UK [3].) In contrast, being overskilled, whether alone or combined with being overeducated, greatly reduces job satisfaction. There is a negative (marginal) effect of being overskilled on job satisfaction of 6.9%. For people who are both overskilled and overeducated, the reduction in job satisfaction is much larger, at 15.2%.

Overeducation and/or overskilling affect job mobility and quitting

Regression analysis reveals that only overeducation on its own or jointly with overskilling increases the probability of quitting as a consequence of job mismatching. Male college graduates who are overskilled only are no more likely to quit than male graduates who are well matched. This finding, when combined with the negative effects of mismatch on job satisfaction suggests that overeducated graduates or those who are both overeducated and overskilled tend to be trapped in jobs that have undesirable characteristics.

Persistence of the effects of job mismatches

Some studies have suggested that overeducation may be a form of investment in training or experience that can boost future returns to human capital [4]. If true, this would mean that mismatch is a temporary phenomenon, which would greatly reduce the need for policy intervention. To determine whether that is the case, studies need to examine the propensity of mismatched workers to remain in mismatched jobs.

Persistence can be examined using a dynamic specification (such as a random effects probit model) that includes a lagged dependent variable. Using this approach with HILDA data (2001–2009) shows that an overskilling mismatch is highly persistent in a manner that is inversely related to the education level [2]; those who are highly educated and overskilled are more likely to stay in this situation for longer. The effect of previous overskill mismatches on present overskilling mismatches is positive but diminishes over time. Accordingly, a college graduate who has never been overskilled for a job has a 4.6% probability of becoming overskilled in the following year. By contrast, a college graduate who was overskilled in each of the previous three years has a 38% probability of being overskilled in the following year. Although data are available for only a limited period, this suggests high persistence or a “scarring effect” from being in an overskill mismatch.

Though college graduates suffer less from persistence than other mismatched workers, they suffer a greater wage penalty than any other group. Empirical results from HILDA also suggest that higher paid college graduates face the largest potential wage losses due to mismatch, which is consistent with higher wages being offered as compensation for taking greater risks. Public policy therefore needs to consider not only the extent and persistence of skill mismatch, but also the size and persistence of the associated wage effects of such persistence if the problem is to be targeted efficiently.

How results with pooled data differ from those with cross-section data

The results reported in the previous sections differ from those of studies based mainly on cross-section data in a number of ways. First, the results show a significant wage penalty for male college graduates who are both overskilled and overeducated, but not for those who are only overskilled or only overeducated. Second, overeducation on its own has no adverse effect on job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is affected only by overskilling on its own or combined with overeducation. Third, they demonstrate that negative effects results in cross-sectional studies may come about because the workers who are mismatched are different and would be paid less anyway. In several cases, the panel estimations reduce the significance of findings compared with those using cross-section data. Together, these differences suggest that policy attention should focus on preventing overskilling, particularly when combined with overeducation, rather than on overeducation alone. Furthermore, job recruitment should aim to secure a better match between skills of new hires and the jobs they fill. Doing so could benefit both employees and employers by boosting productivity, improving morale, and reducing the quit rate [5].

Multi-country panel data sets will enable better cross-country analyses

While the HILDA data only cover Australia, a number of multi-country data sets have recently become available. The OECD-developed Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC) now includes 38 countries. Detailed data on both literacy and numeracy skills enable participants’ skills to be assessed. A study from 2018 uses the PIAAC data to develop a theoretical perspective on mismatch [6]. The authors’ model appears to be superior to previous skill mismatch models in explaining wage variance. Also using PIAAC data, a 2017 study identifies minimum and maximum skill requirements for each job, classifying workers into three categories: matched, underskilled, or overskilled [7]. On this basis, about a quarter of workers are mismatched, of which 16% are overskilled and 9% underskilled.

While PIAAC data allow for multi-country analyses, PIAAC is still essentially a cross-section data set. Another study from 2018 employs cross-country panel data from the European Union Labour Force Survey, covering 28 countries over the period 1998–2012, to estimate the degree of overeducation for full-time employees [8]. The results suggest that overeducation varies significantly by country, ranging from 8% in the Czech and Slovak Republics to over 30% in Ireland, Cyprus, and Spain. The authors note that overeducation is lower in countries with higher female employment, well-developed vocational education, and a high degree of labor market flexibility. Similarly, the authors of a 2015 study note that differences in skill mismatch across countries are related to differences in economic policies such as employment protection legislation which makes it more difficult to get a first job, or housing policies which make it more difficult to move [9].

Yet another study from 2018 used Reflex (Flexible Professional in the Knowledge of Science) data across 13 countries for students who graduated in 2000 and were then re-interviewed five years later [10]. The authors find strong evidence of persistence, consistent with mismatch at the beginning of a career being a trap rather than a stepping stone to matched employment. Again, considerable variations across countries are found.

Limitations and gaps

As mentioned previously, one important limitation of the current research is that the panel evidence discussed above is for a single country (Australia) only. However, the recent emergence of multi-country panel data sets has opened the door to more robust cross-country analysis. Likewise, due to space limitations the focus here has been primarily on male outcomes. The fact that some research indicates mismatch may be even more impactful on women calls for additional efforts to expand the literature across genders.

A broader limitation in the overall literature is the dearth of research concerning horizontal mismatching. Analysis of this phenomenon requires detailed information on both the type of qualifications held and the importance of different types of qualification in particular occupations. A study for the US reports that 20% of college graduates were mismatched horizontally in 1993. Among graduates who were mismatched, those whose studies emphasized general skills, such as a humanities specialization, had a greater likelihood of mismatch but incurred lower costs in terms of wages from mismatching than graduates whose studies focused on acquiring specific skills, such as in medicine, law, and engineering [11], [12]. A study for Sweden found that 23% of men and 17% of women were horizontally mismatched and a further 18% of men and 8% of women were weakly mismatched, with the wage penalty being large for both sexes [13]. Clearly, horizontal mismatch is an important phenomenon requiring study, as is the combination of horizontal and vertical mismatch.

Another question still to be answered concerns the role of employers in generating job–skill mismatch. The European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) notes that empirical evidence on the issue is limited because of the scarcity of appropriate data, such as employer surveys with questions on skill mismatch, matched employer–employee data sets with such questions from both sides of the employment relationship, and administrative data on firm performance and panel data on employers. Preliminary evidence from enterprise surveys supports a positive association between the share of overeducated workers in a firm and firm productivity. Though there may be a wage penalty to being overeducated, such workers are still paid more than the matched workers with whom they work. Precisely why employers hire workers for positions in which they are mismatched is a question that needs to be answered, but adequately linked employer–employee information on this is lacking.

Finally, there is a general limitation related to the process of measuring mismatch, as overeducation measures can be either objective or subjective. Data on overskilling is hard to obtain and typically a self-reported answer to the question of whether the individual has more skills than their job requires. In contrast, overeducation provides a comparison with a large number of other workers in the broader labor market, thus reducing individual reporting bias. Still, overskilling provides a more precise individual assessment of mismatch between each specific individual and their job, albeit being subject to more reporting bias. It could be argued that there is no single best way of measuring mismatch and that each measure offers its own meaning and has its own uses.

Summary and policy advice

Results based on cross-section analysis suggest that overeducation indicates some form of market failure. Such studies find that many college graduates are employed in jobs that do not require a college degree and in which the skills they obtained in college are not fully put to use [3], [11], [12], [13]. The same set of studies finds a wage penalty and reduced job satisfaction for overeducated workers. These findings need to be interpreted with caution, however, because they make no allowance for individual differences and preferences. Some workers may choose to work in jobs for which they are overeducated because they offer compensating non-financial advantages or better future job opportunities, or because it was the only job they could get due to low ability relative to their qualifications. These possibilities suggest that the market may at least in part be working efficiently. Why employers hire workers to positions in which they are mismatched is a question that requires answering, but adequately linked employer–employee information on this is lacking.

In contrast, estimates based on job changes in Australia suggest that there is no wage penalty for male college graduates who are overeducated or overskilled in their jobs. The estimates do show a small wage penalty of just under 6% for workers who are both overskilled and overeducated. They further reveal marginal negative job satisfaction effects for the overskilled, with considerably larger effects for workers who are both overskilled and overeducated. The estimates also reveal that overeducated workers have significantly higher voluntary mobility than workers whose qualifications and jobs are well matched, suggesting that overeducated workers who wish to change jobs can do so. The same is true for workers who are both overskilled and overeducated. There is no significant difference in mobility for workers who are overskilled only.

Employers need to adopt human resource strategies that maximize the inputs of their employees. Government agencies also need to enhance data-gathering initiatives, including household surveys with a panel element and matched employer–employee surveys. Asking workers and employers about the reasons for job mismatches might be the most effective way of finding useful answers. Although overskilled workers are likely to be more productive than their specific job requires, the evidence suggests that they will also have lower job satisfaction than well-matched workers. Employers should therefore be informed of the potential positive and negative effects of overskilling and the value of improving hiring practices to ensure that there is a good match between workers and the jobs they do, particularly when considering the long term.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the authors contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article. Version 2 of the article adds new sections on multi-country data sets and cross-country analyses and also employer–employee data, and new “Key references” [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Peter J. Sloane and Kostas Mavromaras

Types of job/education mismatch

Overeducation: An individual has completed more years of education than the current job requires.

Overqualification: An individual holds a higher qualification than the current job requires.

Overskilling: An individual is unable to fully use acquired skills and abilities in the current job. This is generally measured by employed individuals reporting the degree to which they utilize their skills and abilities in their workplace.

Vertical mismatch: An individual's level of education or skills is less or more than the required level.

Horizontal mismatch: An individual's level of education or skills is appropriate, but the type of education is not.

Undereducation and underskilling can also be found in cases where a job is occupied by someone with less than the requirements of that job and are typically treated as manifestations of skills gaps in the market.

Studies of overeducation

Sources: Carroll, D., and M. Tani. “Overeducation of recent higher education graduates: New Australian panel evidence.” Economics of Education Review 32 (2013): 207–218; Dolton, P., and A. Vignoles. “The incidence and effects of overeducation in the U.K. graduate labour market.” Economics of Education Review 19 (2000): 179–198; European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop). Skill Mismatch: The Role of the Enterprise. Research Paper No. 21. Luxembourg: European Union, 2012; Frenette, M. “The overqualified Canadian graduate: The role of the academic program in the incidence, persistence, and economic returns to overqualification.” Economics of Education Review 23 (2004): 29–45; Li, I., M. Harris, and P. Sloane. “Vertical, horizontal and residual skill mismatch in the Australian graduate labour market.” Economic Record 94:306 (2018): 301–315.

Econometric models

Pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) models, using all survey waves as a large cross-section data set, estimate the overall association between wages and the mismatch variables but cannot be taken to imply causation.

Panel estimation provides the closest estimates of the causal effect of mismatch on wages. Under appropriate assumptions, the random effects model, including a Mundlak correction, can account for the potential correlation between the time-constant unobserved individual differences and the explanatory variables. Where the dependent variable is binary (i.e. where there are only two states, say well-matched or mismatched), a nonlinear probit model must be used.

Calculation of the marginal effects can provide an estimate of the association between the probability of a change in the variable to be explained and a one-unit change in the explanatory variable.