Elevator pitch

One-company towns are a relatively rare phenomenon. Mostly created in locations that are difficult to access, due to their association with industries such as mining, they have been a marked feature of the former planned economies. One-company towns typically have high concentrations of employment that normally provide much of the funding for local services. This combination has proven problematic when faced with shocks that force restructuring or even closure. Specific policies for the redeployment of labor and funding of services need to be in place instead of subsidies simply aimed at averting job losses.

Key findings

Pros

One-company towns help address resource constraints, notably in labor supply, for distant locations.

One-company towns tend to provide relatively high levels of worker compensation that promote attachment.

Employer benevolence, along with self-interest, has often been associated with high levels of service provision—including housing, education, and/or childcare.

One-company towns have often been marked by good civic planning funded by a mix of private and public agencies.

Cons

The susceptibility of one-company towns to shocks tends to be accentuated by specialization and limited other activity in the locality.

Responsibility for funding of local services has often fallen on the company, with little regard for profitability, thereby rendering the town more vulnerable to shocks.

Acquisition of highly firm-specific skills limits the outside opportunities of employees and their re-employment options in the face of closure and job losses.

Lack of information about alternative employment options, as well as insufficient resources to enable mobility, have led to low labor mobility and flexibility.

Author's main message

The number of one-company towns has declined significantly over the last century. Even so, employment concentration remains a serious issue, particularly in the former planned economies. In these contexts, shocks can be hard to absorb, not least when large companies provide basic services and constitute the main fiscal base. When restructuring is required, governments tend to shy away from difficult decisions to avoid large spikes in local unemployment. Rather than drip-feeding fiscal subsidies, which may only prolong a firm’s demise, policymakers should offer employee retraining and/or foster greater labor mobility via informational and fiscal support.

Motivation

There is no widely accepted definition of a one-company town. They can be best defined as geographical locations where there is a very high degree of concentration in output and employment and where, as a consequence, the fortunes of that location are highly dependent on those of the particular company. Cases in which literally one company accounts for the majority of employment in a locality are actually very rare. What is more common is where a location is dominated by one industry.

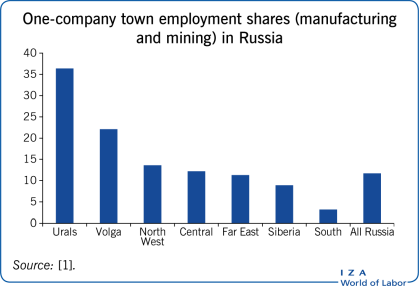

Judgment about what constitutes a one-company town is inevitably subjective. A recent empirical study of Russia has shown that a company employing 5% of the local population is likely to encompass more than one-third of local employment in manufacturing and mining. A manufacturing company with a 10% population share will almost certainly shape the local economy and its citizens’ livelihoods [1]. The central implication is that it does not strictly take monopsony—being the unique source of demand for labor in that particular location—to ensure that a single company can exert a profound influence on the local labor market and, in certain circumstances, local public finances. Such influence becomes particularly significant when faced with adverse shocks and the need to restructure. Companies with concentrated employment tend to be able to lobby government for support due to the latter’s sensitivity to employment losses. In recent decades, the sorts of adjustment costs specific to locations of high employment concentration have been particularly prominent in the economies of the former Soviet Union and, to a lesser extent, in Central and Eastern Europe.

Discussion of pros and cons

Incidence of one-company towns

Although there is no comprehensive and robust measure of the number of company towns globally, it appears that, in addition to the former Soviet Union and China, they are also relatively common in North America, Japan, and parts of western Europe. For example, in Germany, certain sectors—notably automobiles and chemicals—have concentrated employment in particular towns, such as Wolfsburg (Volkswagen) or Ludwigshafen (BASF). In North America, large information technology companies have set up stand-alone campuses that have some resemblance to a company town, although not normally in terms of distance to other labor markets.

Historically, one-company towns have existed in a wide range of economies and sectors but mostly in large countries where access to, and the location of, natural resources—such as minerals, coal, oil, and gas—was the principal consideration. One-company towns came to the fore in the US toward the end of the 19th century, including in the industrial areas of the Midwest. For example, Pullman in Ohio was built for the 6,000 employees of George Pullman’s railway company and McDonald, Ohio, was created by the Carnegie Steel Company. At their peak, there were over 2,500 company towns, accounting for up to 3% of the US population. In the UK, the Cadbury company town of Bourneville and Lord Lever’s Port Sunlight were prime examples. In the Catalonia region of Spain, industrial colonies proliferated in rural areas in the late 19th century, mainly motivated by access to cheap hydro-energy. In India, the Tata family had established a steel town, Jamshedpur, just prior to World War I. Over time, many earlier company towns have effectively merged into larger urban centers—such as Bourneville with Birmingham in the UK—or formed part of a wider industry cluster. The specific policy challenges that such concentration poses have largely evaporated in these cases.

Most company towns have been formed around either mining or manufacturing companies. Mining in particular has tended to be associated with one-company towns, largely because of their geographic location in relatively unpopulated areas. Although these considerations may have become less prominent with modern communications, in many developing countries, in particular, inaccessible locations have promoted high levels of output and employment concentration. There has been a long-standing debate as to whether such activities function as enclaves or can generate positive spillovers, thereby lowering concentration. Some recent evidence suggests that although mining may have negative consequences in the nearby vicinity, particularly for other tradables producers, positive effects on construction and non-tradables, as well as in the wider area, can result [2]. However, the scale of alternative employment opportunities that arise may not be large and shocks to the dominant extractive industry will be highly correlated with any other activities.

Benevolence, attachment, and service provision

A further feature of company towns is that, in many instances, they have also reflected some paternalistic motivation on the part of employers toward their workers. The Hershey Company in Pennsylvania provides a good example, where housing for workers was combined with libraries and hospitals, as well as a highly intrusive owner [3]. In the UK, the Cadbury family also placed great emphasis on the health and education of their workforce, as well as the provision of sports and other facilities. Indeed, in many company towns employment has been bundled together with services—among other things, health, housing, kindergarten, holiday homes—provided by employers, often on a subsidized basis [4]. Aside from motives of benevolence, provision of services was also aimed at enhancing attachment to the firm and limiting turnover. This was especially true in the planned economies of the Soviet Union and China, not least when company operations were located in distant and unfavorable climatic zones. Compensation levels and packages were used as ways of attracting and retaining workers. Subsequently, faced with shocks to profitability—and, in some cases, outright viability—some companies eventually shut down such services, leaving a vacuum that has been hard to fill.

Soviet legacy

In the former planned economies, the relatively large number of one-company towns resulted from the emphasis placed on economies of scale, as well as the wish to select industrial locations for political, as well as economic, reasons. For the most part, these one-company towns have, as elsewhere, been either manufacturing or natural resource based. But the features of concentration in output and employment in the main successor state—Russia—have been principally those of industry, rather than single-firm, concentration. At the end of the Soviet period, excepting the region around Moscow, between 25% and 70% of industrial employment in each of Russia’s regions was concentrated in industries that had four or fewer firms in that region [5]. Even in cases where a larger number of firms were present in a locality, they were often within the same sector, leaving many local economies dependent on a single industry. In seven regions, between 10% and 26% of employment was concentrated in industries with only one firm. Subsequent analysis using data for 2010 has shown that the regions with the highest levels of specialization and concentration in employment have been those with natural resource endowments [6].

By 2010, one-company towns in Russia still accounted for between 13% and 17% of manufacturing employment countrywide and over one-third of manufacturing employment in Russia’s industrial heartland. One-company town firms tended to be characterized by much lower marginal products of labor and much higher marginal products of capital, indicating sizable labor hoarding. Overall productivity was also considerably lower in one-company-town enterprises. These firms were also more heavily indebted, and more financially vulnerable, than comparable firms situated elsewhere.

Shocks and the response

The status of the one-company town has come into sharpest relief when faced with firm- or sector-specific shocks that have triggered a need for restructuring. In the post-Soviet context, such adverse shocks were large and persistent, imposing a need for large order downsizing. A study from 1999 found that labor earnings in Kazakh one-company towns decreased by approximately 1.5% when the share of the population working for the anchor company decreased by 1% [7]. Some anecdotal evidence from Russia suggests that the fall in earnings can be far more substantial when employees accept lower wages in order to retain employment in the face of large demand shocks for a company’s products or services. There is also evidence of the hardship caused by downsizing of the dominant company in China. In both instances, labor hoarding appears to be part of the response to adverse shocks, as are falling real—and sometimes nominal—wages along with loss of social benefits that are historically provided by such companies.

The loss of employment and services has been a highly sensitive and political issue. This sensitivity has been exaggerated when labor mobility has been absent or limited. In addition, many workers have tended to have highly firm-specific skills, making alternative employment options difficult to secure.

One consequence of these sensitivities and firm-specific attachment has been that firms with concentrated employment have often been able to lobby various levels of government for financial support, mostly in the form of subsidies or tax breaks. Policymakers’ typical aversion to spikes in open unemployment rates only compounds this situation. In this way, the employment distribution in one-company towns can influence the allocation of public resources at the cost of supporting labor hoarding and underinvestment in capital stock. This is a contemporary policy challenge in China, particularly in the case of mostly large, industrial state-owned enterprises. Sensitivity to unemployment, along with the power of local lobbies and connected parties, has resulted in slow or absent restructuring. Moreover, financial support for these large and potentially inefficient firms has been made available through a multiplicity of channels, including fiscally (in terms of tax and subsidies) as well as through the banking system or more exotic—and non-transparent—funding processes [8].

One-company towns raise severe and specific challenges, not only because diversity in output and employment is small, but also when the distance to other labor markets is significant or where constraints to mobility bind. One such constraint is when housing is provided through the enterprise. Additional challenges involve a lack of adequate information about alternative employment options and insufficient funding for individuals or families to move to take new jobs. As a consequence, low labor mobility has tended to hold back any required restructuring.

One-company towns that experience difficulties may attract public resources with the specific purposes of stabilizing employment and maintaining some of the services that these firms fund, or provide, in lieu of local government [9]. Financial support to one-company towns by means of subsidies can certainly help stabilize employment levels (although often not earnings) and, hence, limit social tension. However, subsidies have rarely been organized in ways that reflect strategic thinking; rather, they are usually designed as short-term responses to funding shortfalls and as a result of lobbying by enterprise owners or managers. As such, subsidies have mostly been used as substitutes, rather than as complements, to other policies, such as those designed to help retraining and/or foster greater labor mobility. The cost of applying subsidies in this way is not only fiscal but also impedes an effective restructuring and reallocation of resources.

In addition, there is the matter of the services and functions that companies provide to the town’s citizens and the funding basis for those services. This feature has been pronounced in the former planned economies, but employers in other economies have also used service provision as a way of boosting worker retention, as well as improving the quality of basic services, in part for public good reasons.

Arguments for divestiture of such services include the burden that their provision may impose on a company, along with potentially adverse implications for firm competitiveness. The tax system used for supporting local services should in principle be borne by non-distorting taxes. Indeed, in a multi-firm, multi-industry context, it would be surprising if highly firm-specific benefits existed. But when one company and/or one industry dominate, value added in (or credits to) the company or industry provides the main, if not only, resource base for local government and the financing of local services. At full employment, there might exist an equivalence of interest between the company and the local population, but this does not hold when employment reductions (as through restructuring) occur. In this case, a gap potentially opens between those laid off and those retained. The latter may prefer higher wages for themselves as opposed to maintaining services for the whole population. And, obviously, the situation becomes yet starker if the company effectively collapses and cannot afford to pay for either workers or services.

Particularly when linked to restructuring, divestiture of services may be very problematic if the company has basically been fulfilling the role of local government. This is because there may not be a viable agency to take over these services, but also because the funding basis of local government is likely to be highly dependent on the company in the first place. The dependence of local government on revenues from the company or industry will itself imperil services or funding measures aimed at mitigating the impact of job losses.

These factors signal the way in which the tax system and, in particular, the system of local government finance, exerts a material influence. A workable response requires access to resources that are not exclusively locally generated. In large—albeit diverse—federal systems, such as Russia or China, this implies a need for a system of local government finance that recognizes differences in both spending needs and access to resources. An objective would be to adopt resource equalization measures, such as grants, to address these differences. In practice, although some changes to local government finance have been instituted in Russia and other former planned economies, many formerly company provided services appear to have mostly been funded by federal, provincial, or non-budget institutions. This approach does not address, in a sustainable way, the thorny issue of local government funding.

Limitations and gaps

There are enormous limitations on the study of one-company towns. Little contemporary data exist on topics as fundamental as their scale and geographic distribution, let alone on the characteristics of these towns. Most focus has been on the former Soviet countries and China, and little modern research has looked at one-company towns in market economies. In addition, many governments—especially Russia and China—treat financial data about one-company towns in a highly non-transparent way. Even the financing conduits tend to be opaque; for example, in 2008/2009 the Russian state development bank, Vnesheconombank (VEB), was used as the principal conduit for channeling financial resources to one-company towns, but the list, let alone the allocations, was never revealed publicly. Part of the explanation lies in the fact that a significant number of these locations were connected to the military. In the case of market economies, there has been limited focus on one-company towns as their spatial disconnection from wider labor and product markets has generally been less notable than in the former planned economies.

Summary and policy advice

Experience suggests that employment concentration—even when the company or companies in question are privately owned—has been a major factor in shaping policy toward one-company towns. This consideration has been particularly salient when the company has faced adverse shocks that trigger a need to restructure, including through job redundancies. A common governmental response has been to provide subsidies with the explicit purpose of averting or limiting job losses. Such subsidies have been delivered through a variety of channels, depending on the local contexts, but have rarely been time-limited. In most instances—whether in Russia, China, or in historically market-based economies—little explicit distinction has been made between subsidies aimed at supporting a shift to future viability and profitability or subsidies given to avert collapse or, at least, large-scale restructuring and job loss. The latter objective has tended to dominate. Such evidence that is available also suggests that in the more intractable cases, subsidies have been set at values sufficiently high to avoid collapse, but little more. This has certainly been the case in Russia. This strategy amounts to allowing the company to wither away over time without any precipitous collapse. It effectively involves fully depreciating the capital and human assets of the enterprise. Depending on the vintage of the capital stock and the age and skill profile of the workforce, this may be a reasonable strategy for termination, depending, of course, on the scale and duration of support required. But if there are reasonable opportunities for restructuring and redeployment of assets, physical and human, this will be an inefficient and costly approach. When the one company is, or has been, the sole or main provider of services to the workforce and local community, even a strategy aimed at protracted liquidation of the company will still require dealing with the problem of adequate funding for such services.

As one-company towns tend to be located in distant places with relatively limited alternative local employment opportunities, several actions aimed at enhancing employability and mobility will, almost always, be relevant. For younger workers, the main challenges are twofold: ensuring that they have appropriate skills for securing employment elsewhere and ensuring that they are able to move to these alternative jobs.

The first means a focus on training/re-training [10]. There is little evidence whether this has been an actual component of policy, but anecdotal impression suggests that this has mostly been absent. Further, governments typically favor training provided by public agencies. Yet, this is often ineffectual and dissociated from employer demand. A preferable approach would be to use private sector agencies to provide training, once some initial screening has been done. This, however, assumes a case-based approach that can be time and resource intensive.

An alternative approach to addressing the mobility constraint is to provide potentially employable workers with mobility grants and other support. This involves helping displaced workers move to other regions/cities where labor market prospects—including training—are better. In this instance, the two main constraints to be addressed are informational and financial. In the first case, workers are unlikely to have sufficient information about where vacancies exist, as well as the type of vacancies available. This is where either private or publicly provided support on a case basis could be valuable. In the case of mass redundancies, such support needs to be in situ and on some significant scale. In other instances, a mix of in situ and distance (e.g. web-based support) approaches could be considered.

In terms of financial limitations, workers’ mobility is normally restrained by lack of liquidity to cover transport and search costs, as well as lack of access to affordable housing. This can be addressed by providing up-front mobility grants that are calibrated to provide adequate support over a sufficient period of time—say six months—and to be delivered in ways that limit possible abuse. Access to affordable housing tends to be a major constraint that could also be addressed by provision of housing subsidies to workers and/or families that move. Such support is likely to be costly in terms of resources as well as institutional monitoring.

Additionally, in some limited instances, there may be scope for trying to attract jobs to the location—as, for example, by securing new investment. Instruments—notably tax or location incentives—can be considered, subject to the usual caveats. To the extent that a one-company town has created and maintained good infrastructure, there may be opportunities. But distant location and local resource dependence—common features of one-company towns—limit investor interest or require sufficiently large incentives to be provided that they would ultimately nullify the objective.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [9].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Simon Commander