Elevator pitch

Minimum wage increases are not an effective mechanism for reducing poverty. And there is little causal evidence that they do so. Most workers who gain from minimum wage increases do not live in poor (or near-poor) families, while some who do live in poor families lose their job as a result of such increases. The earned income tax credit is an effective way to reduce poverty. It raises only the after-tax wage rates of workers in low- and moderate-income families, its tax credit increases with the number of dependent children, and evidence shows that it increases labor force participation and employment in these families.

Key findings

Pros

There is little causal evidence that minimum wage increases will reduce poverty rates overall or for workers.

Minimum wage increases go primarily to workers in non-poor families.

Some workers lose their jobs when minimum wages rise, pushing their families into poverty.

Most working-age poor people do not work, work part-time, or have wages above proposed increases in the minimum wage.

Earned income tax credits more efficiently provide benefits to workers in poor families and increase employment in them.

Cons

Minimum wage increases at most only have a small negative effect on employment.

Minimum wage increases circumvent the budget process: they are funded neither by government expenditures nor by tax liabilities.

The macroeconomic effects of a higher propensity to spend by those whose wages rise because of a minimum wage hike reduce its negative microeconomic effects on employment.

Minimum wage increases during the expansion phase of a business cycle, when labor demand is growing, can reduce poverty if the employment effects are small.

Author's main message

Introducing or increasing a minimum wage is a common policy measure aimed at reducing poverty. But the minimum wage is unlikely to achieve this goal. While a minimum wage hike will increase the wage earnings of some poor families and lift them out of poverty, some workers will lose their jobs, pushing their families into poverty. In contrast, improving the earned income tax credit can provide the same income transfers to the working poor at far lower cost. Earned income tax credits effectively raise the hourly wages only of workers in low- and moderate-income families, while increasing labor force participation and employment in those families.

Motivation

Societies struggle to remedy the economic plight of their working poor. Politicians and public representatives of unions and churches remind us of the ethical argument that jobs should pay enough to prevent poverty. These are long-standing social concerns. In 1908, the US Supreme Court ruled in Muller v. Oregon that maximum-hour laws are not unconstitutional interferences by a state legislature with an individual’s right to contract. In 1909, the Trade Boards Act in the UK empowered trade boards to set minimum wage conditions that were legally enforceable. But it was not until 1938 that US President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, achieving the goal of a single federal minimum wage and ending all debate about the power of the legislature to establish such labor laws. In his 2013 State of the Union speech, President Barack Obama urged Congress to do so again: “Tonight, let’s declare that in the wealthiest nation on earth, no one who works full-time should have to live in poverty, and raise the minimum wage...”

But for those concerned about the working poor, is another hike in the minimum wage the most effective method of bringing them out of poverty? In the 21st century, efforts to redistribute income are achieved primarily by government tax and transfer policies rather than by direct intervention in the marketplace. The earned income tax credit is a more efficient alternative to reduce the number of people living in poverty. The earned income tax credit is a refundable tax credit available only to workers who live in low- to moderate-income families. As a result, the share of workers receiving this credit who live in poor families will be considerably greater than the share who gain from a general minimum wage hike. In the US, it first entered the tax code in 1975 at a cost of $16.9 billion (in 2013 US dollars) and expanded rapidly. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the cost of the earned income tax credit in tax expenditures for 2013 would be $61 billion, and that 51% would go to families in the bottom fifth of the income distribution and 80% would go to families in the bottom two-fifths [1]. Despite its efficiency in reducing poverty, aside from the US, only Canada and the UK have adopted a version of the earned income tax credit. Thus this paper necessarily focuses on findings for the US.

Discussion of pros and cons

The paper weighs the relative merits of an increase in the minimum wage and enhancements to the earned income tax credit as poverty reduction policies in two core respects: whether and how government should intervene to reduce the number of people living in poverty, and how the minimum wage and the earned income tax credit compare as policy alternatives.

Raising the minimum wage

In a seminal article, future Nobel Prize laureate George Stigler argued against further increases in the nominal minimum wage, writing, “The minimum wage provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 had been repealed by inflation ... and ... the elimination of extreme poverty is not seriously debatable” [2]. But he went on to say that the important questions are whether minimum wage legislation diminishes poverty, and whether there are efficient alternatives. This paper draws on international empirical evidence to explore these two issues.

Empirical evidence on the effects on employment varies

In the US

In a 2014 report, the CBO estimated that a federal minimum wage increase from $7.25 to $10.10—a 39% increase when fully implemented in 2016—would reduce total employment by about 500,000 workers, or about 0.3%, with a two-thirds chance that the employment loss would be between a very slight reduction and one million workers. An increase in the minimum wage would boost the wages of 16.5 million workers who remained employed. But it would reduce the number of people (not workers) in poverty by only 900,000, or about 2% [1].

So, for people who are concerned about the working poor, this minimum wage increase is not a very effective mechanism for reducing poverty. That was Stigler’s conclusion in 1946 for exactly the same microeconomic reasons given by the CBO in 2014. Artificially increasing the wages of low-skilled workers above the wage rate established in the competitive marketplace by the forces of supply and demand would reduce the number of workers employed at this higher wage.

The CBO’s central demand elasticity estimate for affected teenagers was –0.1. That is, a 10% increase in the minimum wage would reduce employment by 1%. The CBO reported the likely range for this elasticity to be from slightly negative to –0.2, with a central estimate of –0.067 for affected adults. These elasticities support the CBO’s prediction that fewer workers would be employed because of a 39% increase in the federal minimum wage rate [1].

In addition to these microeconomic demand effects, the CBO analysis includes macroeconomic effects that take into account the aggregate demand increases that occur because of the more general distributional effects of minimum wage increases. The CBO argued that aggregate demand would increase because the families of the workers receiving the higher wages have a greater propensity to consume than do the owners of the firms who pay them and the families who purchase the products whose prices have risen because of the higher minimum wage. The macroeconomic effects to some degree reduce the negative microeconomic effects on employment that the CBO predicts [1].

The CBO’s demand elasticity range is based in part on consensus estimates in the economics profession beginning in the early 1980s, when it was common to assume that job markets for low-skilled adults and teenagers were competitive and that in such markets, minimum wage increases would come at the cost of modest but significant reductions in their employment.

But the CBO also considered research stemming from the iconoclastic 1995 book by David Card and Alan B. Krueger, which shattered this decades-old consensus using innovative natural experimental designs [3]. It found no evidence of a negative effect on employment—but some evidence of a positive effect. This surprising result of positive employment effects has not proven to be robust, however. A 2008 review of the literature using these innovative natural experimental designs, focusing mostly on research using variations in minimum wage increases across states, concludes that these increases have small but significant negative employment effects that are close to the previous consensus values [4]. One reason for the change in findings between 1995 and 2008 is that the federal minimum wage remained relatively low after 1995. As more states increased their minimum wage above the federal minimum, the greater variation in the data made it possible to more accurately identify the effects of the minimum wage policy.

The intense debate on the appropriate identification strategy continues, especially on how to define relevant control groups along the borders of states with different levels of the minimum wage. The most recent evidence highlights the sensitivity of results to the definition of treatment and control groups and also shows that findings are sensitive to the number of leads and lags (past and future levels) of the minimum wage in the empirical model. When the model uses matched pairs of nearby, rather than contiguous, counties across state borders that are plausibly better controls, negative employment effects from minimum wage increases reemerge [5].

In Europe

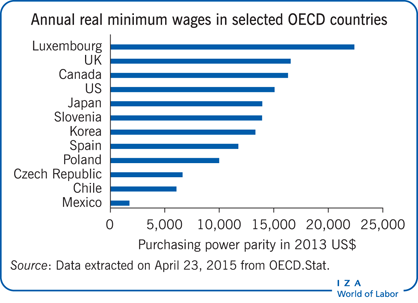

Though the majority of evidence is US-based, minimum wages have also been widely introduced in other countries. Minimum wages have been effectively introduced (either as a statutory minimum or through collective bargaining) in almost all European countries, most recently in Germany, and are higher relative to the average wage than in the US. Still, empirical evidence on the economic effects in Europe is scarce, in large part because of a lack of plausible geographical controls.

A comprehensive evaluation of the economic impacts of different minimum wage regimes in Europe using a variety of empirical strategies shows heterogeneous impacts across age groups and countries, though there has been almost no evidence for adverse employment effects [6]. Focusing on the national minimum wage introduced in the UK in 1999, a study finds zero to marginally positive employment effects of the minimum wage based on differences in regional wage rates before its introduction [7]. To create a quasi-experimental setting to identify these effects, the study exploits the fact that the higher the regional wage rate, the weaker the bite of the minimum wage. For France, a study found substantial negative employment effects in the 1990s. However, a more recent study from 2012 could not identify any significant effect of the minimum wage regime on employment [8]. This more positive result could be driven by the fact that French firms can collect substantial subsidies, which can defray the cost of employer contributions for minimum wage workers.

Empirical evidence on the effects on poverty is more uniform

In contrast to the effects on employment, the evidence that minimum wage increases are not very effective in reducing poverty is much less contentious. Minimum wage increases are not related to decreases in poverty rates because most people living in poverty do not work, and many of the working poor do not work full-time; or they work at hourly wage rates above the new minimum [3], [4]. In fact, after a rise in the US minimum wage, the movement out of poverty of families whose wage earnings increase is more than offset by the movement of low-income families onto the poverty rolls because their earnings fall [4]. Another analysis, using methods similar to those of [3] but with more recent data, also finds no relationship between minimum wage increases and poverty rates even for the working poor [4]. However, a further study found that under certain conditions—when labor demand is growing during the expansion phase of the business cycle and minimum-wage-induced employment effects are small—minimum wage increases can reduce poverty [9]. For evidence outside the US, a UK study finds an easing effect of the minimum wage on wage inequality, especially at the lower ends of the distribution [7]. Because the new German minimum wage of €8.50 was only implemented in January 2015, no ex post evidence exists on its effect. However, ex ante simulations predict that the minimum wage will be an ineffective instrument for poverty reduction, because much of its cost will be offset by reductions in existing means-tested income support and high marginal tax rates [10].

Expanding the earned income tax credit

But what about Stigler’s second question: Are there efficient alternatives to minimum wage increases? On this issue there is very little disagreement. A much less reported finding of the 2014 CBO report is that the earned income tax credit is a far superior way to provide additional income to workers who live in poor families [1]. In the 2014 report, the CBO refers to its 2007 report, which compared the cost to employers of a change in the minimum wage that raised the income of poor families by a given amount with the cost to the federal government of an enhancement in the earned income tax credit that raised the income of poor families by roughly the same amount. The cost of a higher minimum wage to employers (and to consumers who purchase their products) was much larger than the cost to the government (and the taxpayers who provide these revenues) of an enhancement in the earned income tax credit.

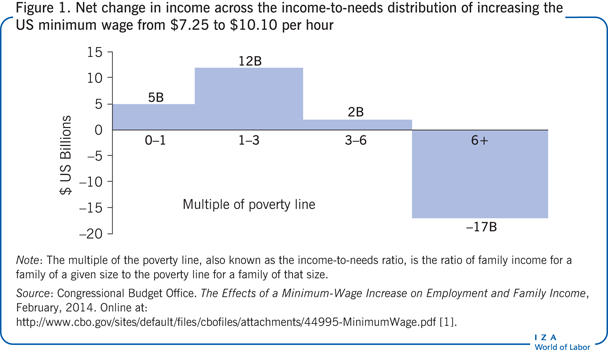

What is not directly mentioned in the 2014 CBO report, but what a careful reader of Table 1 in that report can see (the key values from that table are reproduced here in Figure 1), is how much better an earned income tax credit enhancement rather than an increase in the minimum wage would be for raising the wage earnings of the working poor [1]. Figure 1 reports CBO estimates that show that raising the current minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $10.10 an hour would result in a $17 billion net loss for families whose incomes are six or more times the poverty line (the poverty line for a family of four was approximately $23,500 in 2013) through reduced business profits and dividends and the higher cost of goods and services. It also shows that this $17 billion plus the additional $2 billion coming from the minimum wage increase’s macroeconomic effects on growth will go to those below six times the poverty line. But of this $19 billion, only $5 billion will go to people in poverty (zero to one times the poverty line) [1]. Projections and evaluations for European countries find similar results [6], [7].

The reason for this outcome is that most minimum wage workers who gain from an increase in the minimum wage are not in poor or even in near-poor families. And some workers who do live in poor families have wage rates that are already above the proposed minimum. They just do not work full time. But it is also the case that some of the working poor will lose their jobs or work fewer hours.

The lives of the working poor could be dramatically improved if the real economic costs of the minimum wage were instead devoted to financing earned income tax credit expansion. The earned income tax credit is a much more targeted and effective policy for helping poor families because it raises only the earnings of workers in low- or moderate-income families, and the size of the effect depends on the number of dependent children in those families. Thus, people living in lower-income families receive the vast majority of benefits. In addition, the negative microeconomic effects on employment would be reduced since the earned income tax credit is paid for through the federal income tax rather than directly by the employer. Furthermore, the positive macroeconomic effects would be greater because, presumably, the working poor have the greatest propensity to consume.

As a consequence, the earned income tax credit outperforms the minimum wage in reducing poverty. One empirical study that compares the effectiveness of the minimum wage and the earned income tax credit in helping families escape poverty concludes that the earned income tax credit is far more beneficial for poor households than the minimum wage, because it increases both the labor force participation and employment of family members [11].

Again, empirical evidence has been focused largely on the US. While seemingly a success story in the US, elsewhere the earned income tax credit has been introduced only in the UK and Canada. In the UK, the working families tax credit was introduced in October 1999. An econometric simulation estimated a modest increase in labor force participation of about 30,000 individuals, primarily single mothers. A later empirical study based on labor force surveys confirmed this result, finding an increase in single parents’ employment of around 3.6 percentage points [12]. Canada took the first steps to set up its working income tax benefit program in 2007. Canada’s working income tax benefit program is substantially smaller in size and bite than the US earned income tax credit. No systematic ex-post evaluation has yet been conducted of the program’s labor market effects, but some early simulations point to positive effects on the unemployment rates and average incomes of the targeted population.

Limitations and gaps

Despite more than 75 years of research since the passage of the US Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, the debate over the size of the employment effect of a minimum hourly wage rate increase rages on. But even relatively small elasticities like the ones used in the 2014 CBO report [1] find non-trivial reductions in employment. This is in contrast to the effect of increases in the earned income tax credit, which unambiguously increases labor force participation and employment [11]. These findings suggest that subsidizing the employment of workers in low- and moderate-income households is more likely to increase their employment than raising the minimum wage. But by how much more is still controversial. Furthermore, it is unclear how much an increase in the earned income tax credit reduces the number of hours worked by those who are already employed. This occurs because, after a short disregard period during which a worker’s additional income does not affect the amount of the earned income tax credit benefits, the phase-out period begins and a worker’s benefits start to decline, lowering the effective wage rate [13].

A further limitation of the existing evidence on the minimum wage and the earned income tax credit is its primary focus on the US economy. To what extent the insights of this research can be applied to other economies is unknown. It will be interesting to compare the initial evaluation results of the general minimum wage introduced in Germany in 2015 with the introduction of the new minimum wage in the UK in 1999. In general, it would be advisable to expand the empirical research on minimum wage systems and on earned income tax credit systems. The two more-recently introduced tax credit systems in the UK and Canada have not yet been comprehensively evaluated. It would also be of interest to gather more evidence on smaller, targeted tax credit instruments in other countries (one example being the wage top-up for low-income workers in Germany).

Summary and policy advice

At the turn of the 20th century, people in the US who were concerned about the distributional consequence of a market-driven economy turned to government to improve minimum living standards and reduce poverty by intervening directly in labor markets through minimum-wage and maximum-hour legislation. In the absence of government tax and transfer programs, such direct interventions were seen as the only means of achieving those goals. But it was not until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act established these standards at the federal level and ended the debate about the power of government to establish such labor laws. Since then, the empirical debate from an economics perspective has not been over the social goal of eliminating poverty but rather has focused on the two questions first posed by Stigler [2]: Does minimum wage legislation diminish poverty, and are there more efficient alternatives? The evidence examined here suggests that the answers are “not much” and “yes.”

At the turn of the 21st century, minimum wage legislation plays a minor role in US labor markets. The overwhelming majority of American workers earn hourly wage rates that are determined by market forces without the intervention of government. These wage rates are not only far above current federal and state minimum wage rates, but are high enough that they will not be affected even if the federal minimum wage rises to $10.10 per hour.

Minimum wage increases affect the lowest-skilled workers at the bottom of the wage rate distribution. Most empirical research has examined how these minimum wage increases have affected their employment. The CBO estimated that an increase in the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour will reduce employment by some 500,000 jobs, with a band of 0 to 1,000,000 around these estimates [1]. While these estimates remain contentious, they are plausible. The evidence on the employment effects of minimum wages in Europe is mixed.

The reduction in employment in part explains why past minimum hourly wage increases have not been found to reduce poverty. But a more important reason is that there never was a one-to-one relationship between a worker’s wage rate and the income of that worker’s family. And this fuzzy relationship, which Stigler also talked about in 1946 [2], has become even fuzzier as the number of workers per family has increased and the share of minimum wage workers who are their family’s primary earner has decreased. These changes help explain why the earned income tax credit has increasingly become a more target-effective way of providing employment-based subsidies to the working poor. The earned income tax credit is now the most important transfer program in the US for providing income to poor families and one that the CBO found in 2007 to be a more cost-effective way of doing so than increasing the minimum wage. And that is why policymakers interested in reducing poverty in the US should increase the earned income tax credit rather than the minimum wage.

Like the US, many European economies are experiencing similar increases in the number of low-income families and working poor. The argument that the distributional effects of minimum wage policies are too dispersed to be effective in reducing poverty applies to many countries. Introducing and fostering tax credit systems similar to the US earned income tax credit could also be attractive to these countries as a more focused instrument than a minimum wage increase in fighting poverty. Direct individual subsidies can be designed and targeted much more specifically, making them more appropriate for particular target groups.

Rather than increase the rewards of work for all minimum wage workers, the earned income tax credit increases the hourly wage rate only of workers in low- or moderate-income families. The preponderance of the empirical evidence is that earned income tax credit enhancements have substantially reduced poverty rates and increased employment. Nonetheless, the earned income tax credit is not a panacea. In its phase-out period, the credit may to some degree result in fewer hours of work above this income level. In addition, the increase in low-skilled workers drawn into the labor market because of the earned income tax credit will lower wages to some degree, thus allowing employers to capture part of the subsidy. Finally, because it is a tax credit, expansion of the earned income tax credit is part of the budgetary process and may be harder to achieve than an increase in the minimum wage whose costs to the public are less visible.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Richard V. Burkhauser

Earned income tax credit

Source: Tax Policy Center. Tax Policy Briefing Book. Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, 2014. Online at: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/key-elements/family/eitc.cfm; Hotz, V. J., and J. K. Scholz. “The earned income tax credit.” In: Moffitt, R. A. (ed.). Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States. Chicago, IL: National Bureau of Economic Research, University of Chicago, 2003; pp. 141–198.