Elevator pitch

Countries have adopted a variety of legalization programs to address unauthorized immigration. Research in the US finds improved labor market outcomes for newly authorized immigrants. Findings are more mixed for European and Latin American countries where informal labor markets play a large role and programs are often small scale. Despite unclear labor market outcomes and mixed public support, legalization will likely continue to be widely used. Comprehensive legislation can address the complex nature of legalization on immigrants and on native-born residents.

Key findings

Pros

Legalization allows unauthorized immigrants to come out of the shadows, reducing risks of workplace exploitation and increasing mobility.

Better job matches may result from legalization, increasing wages and non-pecuniary benefits.

Tax revenues may rise as more immigrants start paying taxes or contribute more as their incomes rise.

Legalization may result in increased investment in education and health and lead to reduced crime.

Legalization can address some humanitarian and political concerns by allowing access to social services, higher education, and equal protection under the law.

Cons

Legalization programs may attract more unauthorized immigration, which may have security implications.

Legalization may have negative consequences for workers who compete with newly regularized immigrants, through increased competition for jobs and lower wages.

Government budgets may be negatively affected due to increased spending on social services and use of tax credits.

Issues of fairness make legalization a politically contentious tool for dealing with unauthorized immigrants.

Author's main message

Legalization allows unauthorized immigrants greater labor market and geographic mobility, access to health and social services, and equal protection under the law. Comprehensive legislation can bring undocumented immigrants out of the informal sector and into the formal one, thereby increasing tax revenues. There are clear benefits from programs that combine access to labor markets with limitations on new migrant inflows. These programs can boost net benefits to the receiving country while reducing security concerns.

Motivation

Understanding what prompts people to migrate in an unauthorized status and how they perform after legalization is vital for designing effective immigration policy. Countries may be motivated to legalize migrants when they have a large stock of unauthorized immigrants within their borders. Policy options to address and reduce the level of unauthorized immigration range from stepping up border enforcement and deportation to granting temporary access or providing a path to citizenship. Proponents of legalization believe that it can help migrants who are “living in the shadows,” boost tax revenues, regulate the informal economy, prevent worker exploitation, increase human capital, reduce crime, and support national security. Furthermore, legalization is a humanitarian action that can keep families together and improve access to social services and higher education.

Much of the political debate in the US and Europe has focused on how to address the large stocks and persistent flows of unauthorized immigrants. Legalization is often contentious as many people believe that immigrants can hurt the labor market prospects of native-born workers and previously authorized immigrants and impose costs on government and society. In addition, opponents feel that legalization encourages additional unauthorized immigration and rewards law breaking. Some feel that it is unfair that certain immigrants are “cutting the line,” so to speak.

Studies use multiple terms for migrants who cross borders without authorization: “illegal,” “undocumented,” “irregular,” and “unauthorized immigrants”; and for adjustment of legal status: “legalization,” “regularization,” “normalization,” and “amnesty.”

Discussion of pros and cons

Key trends in unauthorized immigration and legalization programs

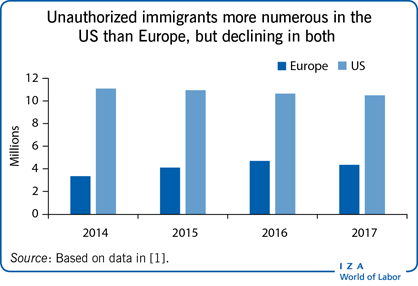

Millions of migrants cross borders without authorization each year. The global stock of unauthorized immigrants has been estimated in the tens of millions. As seen in the Illustration, the largest share, approximately 10.5 million, live in the US [1]. There were also an estimated 3.9–4.8 million irregular migrants in Europe as of 2017, with large stocks in Germany, Italy, Spain, France, and the UK [1]. While still at high numbers, especially for those seeking asylee and refugee status, stocks and flows have subsided in recent years due to increased border enforcement and reduced job opportunities in receiving countries. The decline is most notable for the US, where the unauthorized population fell by 1.7 million people, or 13%, from 2014 to 2017. Europe, meanwhile, experienced declines of approximately 9% from peak levels in 2016.

In Europe, legalization efforts have been wide-ranging, numerous, and of a smaller scale [2]. In the 1970s, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and the UK used regularization programs to address unauthorized migration that occurred after guest worker programs were terminated [3]. Meanwhile, countries like Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, which experienced waves of irregular migration following periods of economic growth, enacted multiple programs in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s [2]. In total, between 1996 and 2008 over 68 programs were enacted in Europe, leading to an estimated 4.2 million immigrants becoming regularized [2]. These programs vary on the extent to which they focus on certain migrants from certain countries as well as the level of access they grant to labor markets and government services. For example, prior to 2004 the numerous regularization programs in Spain had proof of long-term residency as the main requirement. However, the 2004 reform was pitched as a program to regularize workers rather than residents, and thus tied authorization to having an employment contract [2]. Irrespective of the many differences, a policy in one country can have a direct impact on others, because the EU allows free movement of labor within its borders.

In the US, legalization programs have been fewer, but of a larger scale. Similar to many European countries, the US experienced increases in inflows of undocumented economic migrants in the 1980s. In 1986 it passed its most recent comprehensive immigration reform legislation, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). The act included two amnesty programs granting almost three million immigrants legal permanent residency and a path to citizenship. This makes it one of the largest, one-time authorization programs ever enacted. The first program, a general amnesty program, granted legal permanent residency status to immigrants with long-term ties to the US. The second program was population-specific, primarily aimed at agricultural workers, and allowed for shorter stays in the US. Since the 1986 legislation, the US has introduced smaller-scale programs, such as the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA), in addition to strengthening its borders and interior enforcement.

Since IRCA, other authorization programs have been proposed but not enacted by the US legislature. One of the most prominent federal proposals is the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors or DREAM Act. Introduced in 2001, it offered to adjust the legal status of approximately 2.1 million children who arrived in the US as unauthorized immigrants. While this act is unlikely to pass in the near future, states have granted their own in-state tuition waivers to undocumented youths, and in 2012 President Obama issued an executive order to grant Deferred Action to Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Those granted DACA status were not at risk of deportation and were granted temporary work authorization status.

As countries consider introducing new programs, it is important to review the possible mechanisms through which legalization affects newly authorized immigrants, their labor market competitors, and government budgets.

A framework of labor supply and demand of newly legalized immigrants

The impact of legalization programs differs from that of immigrant inflows because these programs do not change the number of immigrants in a country but rather their status. If legalization programs do not incentivize new migration flows, the total number of foreign-born individuals should remain the same. It is unclear, however, what will happen to the total supply of workers in a given market as labor force participation rates for newly authorized immigrants could change. The supply of workers could increase if some previously non-working immigrants join the labor market after being legalized, or decrease if others stop working or work less thanks to higher wages and access to government benefits.

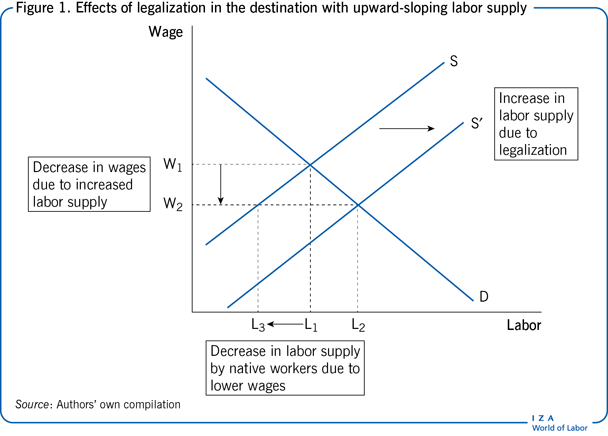

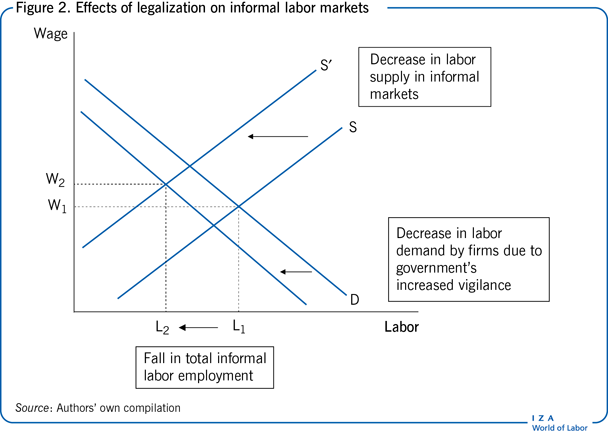

While changes in total labor supply are difficult to predict, it is likely that the specific labor market in which newly authorized immigrants work would change as a result of increased legalization. Work authorization means that previously unauthorized individuals can move from informal labor markets, where they may face lower wages and bargaining power, to formal ones, where they earn higher wages, gain access to benefits, and provide a greater tax contribution. The result is that the labor supply in formal labor markets likely expands while the supply in informal markets likely shrinks. These shifts should have positive wage effects for newly authorized immigrants, as formal wages tend to be higher than informal ones.

Labor demand also may be affected by authorization and accompanying policies, like increased enforcement of work authorization. In informal markets the demand for labor could fall, as a greater emphasis on compliance makes hiring informal workers more costly. By the same token, demand for labor could also fall in formal markets as compliance costs increase. However, lower turnover among now legal workers could lower hiring costs, thereby raising demand.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 depict the formal and informal labor markets where newly authorized immigrants, previously authorized immigrants, and native-born workers are perfect substitutes for each other. In Figure 1, authorization causes the labor supply curve of formal workers to shift to the right, from S to S´. Formal wages fall from W2 to W2. Total labor (employment) rises from L1 to L2. The number of immigrant workers rises and is equal to the rightward shift of the labor supply curve, or L2 – L3. With an upward-sloping labor supply curve, employment of native-born workers falls from L1 to L3 because only L3 native-born workers are willing to work at the new, lower wage, W2.

Meanwhile, in Figure 2 immigration authorization causes the supply of labor in informal markets to shift to the left, from S to S´. Labor demand D also likely shifts left, as firms respond to the government's increased vigilance of work authorizations. The wage effects are indeterminant, but likely not to rise dramatically. Meanwhile, total informal labor (employment) falls from L1 to L2, reflecting a decrease in the number of individuals working “in the shadows.”

What happens to native-born workers and remaining unauthorized immigrants partially depends on whether or not they move or alter their labor supply in response to a change in the overall supply of authorized workers. Absent any response, the basic neoclassical model predicts the formal wages of native-born and previously authorized workers would fall in the education and experience groups in which legalizations are concentrated. If, however, these groups respond by moving to areas less affected by the authorization programs, the labor supply shift will be smaller, leading to more muted changes in wages for those who remain. It is also possible that native-born and previously authorized immigrants respond by moving into informal markets, despite the higher costs. This would mute the wage effects in informal markets as well.

In sum, the overall change in employment and wages for all groups as a result of legalization depends on several factors. The first is the size of formal labor markets relative to informal ones. The second is the mobility of the native-born and previously authorized population. The third is the restrictiveness of accompanying enforcement policies and firms’ response to these. Thus, the actual impact on wages and employment is an empirical question.

Earning and employment effects for newly authorized immigrants

Earning effects

Overall, studies of authorization find mixed effects on earnings, largely depending on the country and program being studied. In the US, researchers have examined the impact of IRCA on groups of legalized immigrants and used comparison samples of native-born individuals using data from two surveys, the Legalized Population Survey and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth–1979 [4], [5]. Studies have found that following legalization, the average wage increase for Latin American male immigrants was 6%–13%. Larger effects were found among immigrants with more education and better English proficiency [4], [5]. It is possible that these immigrants had more to gain and more bargaining power since they had larger investments in their human capital. A follow-up study found gains for female immigrants that were even larger than those for their male counterparts [4]. Research further shows that these gains may have been due to changes in occupations from lower- to higher-paid jobs. Also in the US, a study of NACARA of 1997 finds increased earnings of newly legalized male immigrants [6], while a study of DACA finds an increase in wages for those at the lower end of the earnings distribution [7].

For Europe, despite the large number of regularization programs, the research testing for wage effects is sparse and inconclusive. This partially is due to difficulties in identifying and obtaining data on a reasonable control group, that is, immigrants who do not qualify for the authorization program but are similar to those who do or areas that are less affected by the program. One exception is a recent study of Spain, which exploits the large size and unanticipated nature of the 2004 authorization program and pre-program settlement patterns of immigrants to identify less affected areas [8]. The study finds an increase in wages for highly educated immigrants, in line with these workers being able to find better, formal jobs after being authorized. Wages for less educated immigrants, however, decrease slightly, despite increased movement across jobs and locations following the program.

The last point highlights that wage effects for newly authorized immigrants depend on how much mobility is granted under legalization programs, the pre-existing size of the informal sector, and other barriers to formal employment. For example, an earlier study of France suggests that wages did not change much after the 1998 regularization program, a result attributed to the lack of worker mobility [9]. Similarly, a recent analysis of the 2018 program in Colombia that authorized almost 500,000 unauthorized Venezuelan refugees finds no impact on formal or informal wages [10]. This absence of impacts speaks to the fact that the program did little to change if and where Venezuelans worked in Colombia. Many Venezuelans likely worked in the large informal sector prior to the program, and labor restrictions likely limited the number who were able to move into formal work.

Employment and unemployment effects

Economic theory is ambiguous regarding the overall impact of legalization on employment. Two studies of IRCA in the US find that male immigrants were more likely to move into the pool of unemployed workers as they searched for better jobs while female immigrants left the labor force completely [4]. The study of NACARA also finds that legalized male immigrants experienced a decline in employment rates [6]. These declines in labor force participation may be due to higher reservation wages (the lowest wage at which a worker is willing to work), better access to social benefits, increased costs for firms, and discrimination. Meanwhile, studies of DACA find increases in employment and decreases in unemployment among the eligible population [7].

Studies of European countries find more mixed evidence on changes in employment, with programs that do not require work contracts leading to smaller increases in employment, particularly formal employment, than those that do require a job. For example, after the 1990 regularization program in Italy that linked regularization to residency rather than employment, approximately 80% did not have official employment at the time and many were unable to renew their residency permits two years later due to a lack of an employment contract [9]. Meanwhile, in Greece, 40% of individuals who received temporary authorization status following the 1998 reform were unable to qualify for the second wave of more permanent status due to the lack of a formal, employment contract and evidence of related social insurance contributions [9]. It is possible that lack of information about eligible jobs, confusion, and uncertainty over enforcement limited the employment effects. In addition, employers may have fired previously undocumented workers who were transitioning to legal status because the cost of this legal labor was higher. For example, programs in Spain in the 1990s were accompanied by efforts to reduce the size of the informal sector. This made employers more reluctant to hire informal workers, including newly authorized immigrants who previously might have held these jobs [9].

On the other hand, the increased employment effects are larger when programs require work authorization. For example, following the 2002 amnesty initiative in Italy, which linked legalization to having a one-year employment contract, eligible unauthorized immigrants were 26.2 percentage points more likely to be employed prior to receiving a residency permit than those ineligible for the amnesty [11]. The program also incentivized long-term employment by making authorization renewal contingent on employment. One to two years after the program, newly authorized immigrants remained more likely to be employed. Similar increases in employment are seen from the 2004 authorization program in Spain, which made authorization contingent on having a six-month employment contract. Employment increased for both high- and low-wage immigrants, and some newly authorized immigrants moved to larger and possibly more stable employers after the initial six-month contract. Increased vigilance of informal markets also encouraged newly authorized immigrants to shift into the formal sector [8], [9]. Similar shifts are seen in Colombia, where formal employment increases slightly for newly authorized Venezuelan workers [10]. Nonetheless, programs that tie regularization to work contracts might not lead to high-quality matches or long-term employment [9].

Effects on native-born workers and earlier immigrants

Most empirical work has examined the impact of new immigration flows rather than the impact of newly legalized immigrants on natives and previously authorized immigrants. The majority of studies on new flows find adverse employment and wage effects on earlier immigrants. Such results are not surprising since immigrants are likely to enter the same labor market based on their similar educational experiences, language abilities, occupations, and settlement patterns.

Research on the effects of newly authorized workers on native born or earlier immigrants is sparse. One study from the 2004 program in Spain finds no change in formal native-born employment, but does find a reduction in informal native employment following the 2004 reform [8]. This is attributed to increased enforcement of informal markets that accompanied the authorization program rather than increased competition from immigrants. Meanwhile, research on the 2018 authorization program in Colombia finds no change in informal employment and only very small declines in formal employment for highly educated Colombian workers [10]. This is because the informal labor supply likely did not change, while the formal one for highly educated workers did, because Venezuelan workers are on the whole more educated than Colombian workers.

There is also potential for discrimination against legal immigrants or native-born workers who may be mistaken for undocumented immigrants following authorization programs. This confusion was found to be the case in the US when IRCA's amnesty programs were coupled with new sanctions on employers for hiring undocumented workers. The wages of all Latino workers fell an estimated 8%; employment rates also fell [12].

Fiscal impacts and beyond

Immigrants who are granted legal status likely become eligible for some social welfare programs, depending on the country's eligibility rules. In such cases, fiscal costs rise. In addition to the costs of programs such as social security, unemployment, and welfare, some countries grant or require access to language and civics classes for immigrants. For example, some regularization programs in Europe include social programs aimed at integrating migrants into society and offer active labor market programs to prepare immigrants for jobs. While costly, such programs could have a positive impact on long-term economic outcomes of immigrants. If other family members migrate to join the newly legalized immigrants, additional costs may be incurred for their education and health care.

Some or all of these additional costs may be offset by increased tax revenues. While some undocumented immigrants may already pay income and payroll taxes using fraudulent documents, and nearly all will pay sales or value added taxes at retail establishments, moving workers into the formal job market will boost payroll taxes, especially if wages rise for newly legalized workers. One study of immigrant regularization in Spain showed that the payroll tax revenue increased by €4,398 per each newly legalized immigrant [8]. On the other hand, tax payments will fall if legalization of immigrants has negative wage impacts on native-born workers or other immigrants. In a study of legalized workers under IRCA in California, the authors find that the number of state income tax filings increased but the net effect on state coffers was negative as those receiving legal permanent residency became eligible for tax credits under the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) [13]. Despite uncertainty over short-term tax intake, overall legalization may improve the longer-term sustainability of public pension systems by increasing the number of contributing working-age adults.

The debate over legalization also goes beyond labor market and fiscal impacts. Some people believe that regularization will encourage rule breaking and is unfair to immigrants who have applied for legal status through regular, official channels. Others believe that there is no alternative, that mass deportation programs violate human rights and are impractical. Research has also begun to document links between legalization and remittances, and consumption and investment decisions. A growing number of studies suggest that legalization reduces crime rates, increases reporting of crimes, and encourages investments in education [5].

Limitations and gaps

Research on the impact of authorization programs remains limited for several reasons. First, in the US there have not been many programs, and thus most of the research focuses on the two large-scale amnesty programs that resulted from the 1986 IRCA. While many more programs have been implemented in European countries, there is a lack of good data sets with information on immigrants’ authorization status, employment, and earnings. This complicates efforts to count and track unauthorized and regularized immigrants. Many representative surveys do not include questions on legal status, which is a sensitive topic; inclusion may result in unanswered questions and unreliable responses. As a result, researchers often create a proxy variable for legal status based on demographics of the typical unauthorized immigrant derived from specialized data sets or case studies [4].

Second, methodological issues create limitations. Finding valid comparison groups or regions is difficult, and the assumption that becoming legal is an exogenous event may be too strong for modeling the true nature of the impact of legalization on labor market outcomes.

Third, some programs are difficult to assess because of implementation challenges. For example, lack of publicity and confusion can create delays or low take-up rates among immigrants eligible for legalization programs or mechanisms. On the other hand, some countries were overwhelmed by applications for regularization programs, which caused backlogs. Fraud and corruption can also plague the process and cloud the picture. Documents can be forged, and fake applications may be submitted as some people learn what is needed to game the system. For example, some programs demand evidence of work authorization, and there have been allegations of public officials selling these illegally.

Summary and policy advice

Overall, legalization programs have been more positive in terms of wages in the US than in Europe, while evidence on employment incidence and job characteristics is mixed in both regions. It is possible that these observed outcomes are due to the smaller scale of the European regularization programs, variation in whether or not regularization is tied to residency or employment, and the larger size of the informal sector in many European countries.

The need for authorization programs will remain strong as long as the disparity in global standards of living persists and there are not enough visas for all who wish to migrate. Policymakers who seek to reduce the number of unauthorized immigrants in their country often propose comprehensive legislation that is intended both to bring immigrants who are living in the shadows into the mainstream and to deter further inflows of unauthorized immigrants. Deterrence efforts such as increased border enforcement and employer penalties have been used in the US to reduce future inflows of unauthorized immigrants.

However, these policies also come with explicit administrative and implementation costs in the form of enhanced manpower and enforcement infrastructure. There also might be implicit costs from reducing return migration, increasing family reunification efforts, intensifying smuggling, and forcing migrants to cross borders at more dangerous and difficult locations. Raising penalties for hiring undocumented immigrants may reduce the demand-side or pull factor of undocumented immigration, but it also may result in more discrimination against legal immigrants if employers are worried about increased enforcement of immigration violations.

Countries that are concerned with potential rising costs to government coffers could link authorization to employment or impose waiting periods on eligibility for certain government services. For countries with a heavy reliance on an immigrant workforce, one way to achieve the goals of legalization would be to issue temporary work visas to coincide with demand for certain labor groups. To continue to provide a flexible pool of labor, immigrants with a temporary visa could be allowed to change jobs rather than being tied to a particular employer. For immigrants with special skills or long-time ties to a particular employer, a path to permanent residency could be provided as well.

Countries should continue to consider legalization reforms as a way to benefit immigrants and society as a whole. However, in many places federal immigration reform has stalled and there is a lack of consensus on immigration policy and how to address the stock of undocumented immigrants, especially in light of the recent global pandemic, recession, and the worldwide migrant crises.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The authors further acknowledge the exceptional research assistance provided by Ha Bui, Adham Mousa, Norbert Oros, and Freya Woods, whose assistance with the literature review and editing were invaluable. Previous work of the authors, in particular [4] and the further reading, contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article. Version 2 of the article includes a new Illustration, a new Figure 2, significantly updates the text, and includes new “Key references” [1], [2], [7], [8], [10], [11], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Cynthia Bansak and Sarah Pearlman

Unauthorized immigrants

The term unauthorized immigrants refers to people who have entered a country without permission—either by crossing the border surreptitiously or by using false documents—or people who entered legally but then “fell out of status” by overstaying their visa, or going beyond the scope of their visa. This latter group may include students, temporary workers, tourists, and those ultimately denied asylum status.

Legalization and regularization of immigrants

Legalization, the term commonly used in the US, confers authorized immigration status on people previously categorized as unauthorized, undocumented, or irregular immigrants. In the US, legal status is typically adjusted to legal permanent resident (LPR) status, with the potential of eventually becoming US citizens. Those who are granted LPR status are often referred to as “green card” holders.

Regularization, the term commonly used in Europe, grants either temporary or permanent legal status, through programs or mechanisms, to people previously categorized as unauthorized, undocumented, or irregular immigrants. Programs are one-time measures, while mechanisms are part of a more comprehensive policy. Other terms also used in connection with regularization are normalization, adjustment of status, and toleration.

Source: Kerwin, D., K. Brick, and R. Kilberg. Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States and Europe: The Use of Legalization/Regularization as a Policy Tool. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2012.