Elevator pitch

Some studies estimate that the value of time spent on unpaid caregiving is 2.7% of the GDP of the EU. Such a figure exceeds what EU countries spend on formal long-term care as a share of GDP (1.5%). Adult caregiving can exert significant harmful effects on the well-being of caregivers and can exacerbate the existing gender inequalities in employment. To overcome the detrimental cognitive costs of fulfilling the duty of care to older adults, focus should be placed on the development of support networks, providing caregiving subsidies, and enhancing labor market legislation that brings flexibility and level-up pay.

Key findings

Pros

Informal caregivers such as adult daughters or spouses may provide a better quality of care than formal care providers such as home help or nursing home care.

Flexible working hours may help caregivers balance care obligations and employment by providing them with a sufficient income and a social network through work.

Interventions to improve carers’ employment opportunities can provide a form of respite and self-esteem, and cash allowances can compensate caregivers for their reduced working hours and costs of providing care.

Evidence from recent long-term care reforms in Scotland and Spain suggests that caregiver support can have a significant impact on caregiver well-being and mental health.

Cons

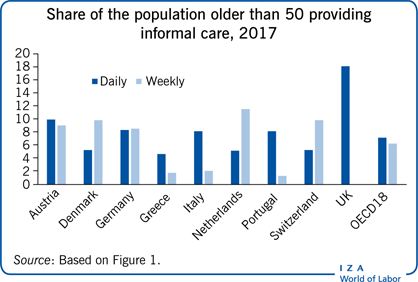

A significant share (13%) of people aged 50 and over report providing some adult informal care at least weekly in OECD countries.

Providing care reduces leisure, depresses work opportunities, and becomes a well-being burden to many individuals.

Most evidence suggests that caregiving has a relatively modest impact on labor force participation, although it can reduce the hours of work.

Care leaves are available to one-third of European employees; however, statutory leave for caregivers of older adults and flexible work arrangements are far less common than similar arrangements for child carers.