Elevator pitch

Older people in developed countries are living longer and healthier lives. A prolonged and healthy mature period of life is often associated with continued and active participation in the labor market. At the same time, active grandparents can offer their working offspring a free, flexible, and reliable source of childcare. However, while grandparent-provided childcare helps young parents (especially young mothers) overcome the negative effects of child rearing on their labor market participation, it can sometimes conflict with the objective of providing additional income through employment for older workers, most notably older women.

Key findings

Pros

Healthy and long-lived older people can offer a free, reliable, and flexible source of childcare to parents.

Parents participating in the labor market in developed countries make extensive use of grandparent-provided childcare arrangements.

Grandparent-provided childcare helps young working parents, particularly young mothers, to remain attached to the labor market, thus overcoming the negative effects of child rearing on female labor supply.

Cons

Grandparent-provided childcare reduces the labor supply of senior workers, especially those grandmothers who are already less attached to the labor market, e.g. working part-time.

Reliance on informal childcare provided by grandparents may reduce the geographic mobility, and consequently job opportunities, of households.

There is a trade-off between grandparent-provided childcare by senior workers and their own labor supply, particularly when the potential unsustainability of living off welfare and pension provision is taken into account.

Author's main message

Surveys of people aged 55 or older show large time transfers to their offspring in the form of grandparent-provided childcare. These transfers help young parents to reduce the cost of bringing up children (i.e. reduced labor market attachment) and thus boost the labor supply of young mothers, in particular. However, the existence of a time constraint implies that these transfers sometimes come at the expense of older workers’ labor supply, which is a trade-off that should be taken into account when designing retirement, family, and taxation policies. Such policies could include reduced labor income taxes for the elderly and/or temporary “grandparental” leave while grandchildren are very young.

Motivation

According to the 2014 American Community Survey of the US Census Bureau, there are approximately 70 million grandparents in the US, which represents around two-thirds of American people aged 50 or older. One empirical research study estimates that the median age that Americans become grandparents is around 51 for men and 48 for women [1]. This means that the vast majority of American grandparents have grandchildren while they are still of working age.

The demographic incidence of grandparents in Europe is similar, though reported in a more disaggregated way, i.e. the share of European women of 50 years of age or older who are grandmothers is approximately 67% in the UK and France, 63% in Germany, and 60% in Spain and Italy [2]. For men, the figures are lower as a result of their shorter life-expectancy and age gap with their wives: approximately 58% in the UK and France, 53% in Germany and Spain, and 45% in Italy. By adding the average age of women at the point of birth of their first child across two adjacent generations, it has been estimated that European grandmothers also have grandchildren at a relatively young age, although slightly later than Americans: about 53 years old in the UK, France, and Italy, 52 in Germany, and 55 in Spain [2].

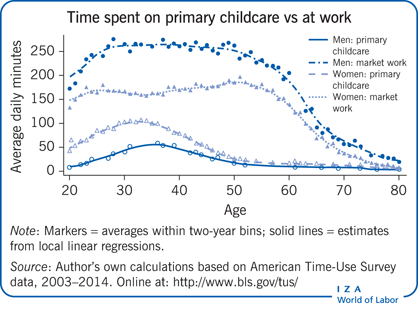

These working-age grandparents make large time transfers to their offspring in the form of grandparent-provided childcare, which is the main component of informal childcare arrangements in developed countries. The OECD defines informal childcare arrangements as unpaid childcare provided by grandparents, other relatives, friends, or neighbors. According to this source, in 2014 about one in four children between zero and five years of age in OECD countries were recipients of informal childcare arrangements during a typical week. Although no disaggregation is available to disentangle the importance of grandparents, other relatives, friends, or neighbors, it is clear from other sources that grandparents account for the bulk of informal childcare arrangements. For instance, according to the April 2013 issue of the US Census Bureau’s Household Economic Studies, in 2011 grandparent-provided childcare accounted for more than 70% of informal childcare arrangements. One study finds that in northern Italy this share is about 90% for families with two working parents [3]. Figure 1 shows the proportion of families using informal childcare arrangements as well as hours of use in 2014 in Europe, by age of the child.

Discussion of pros and cons

Time transfers from working-age grandparents to parents

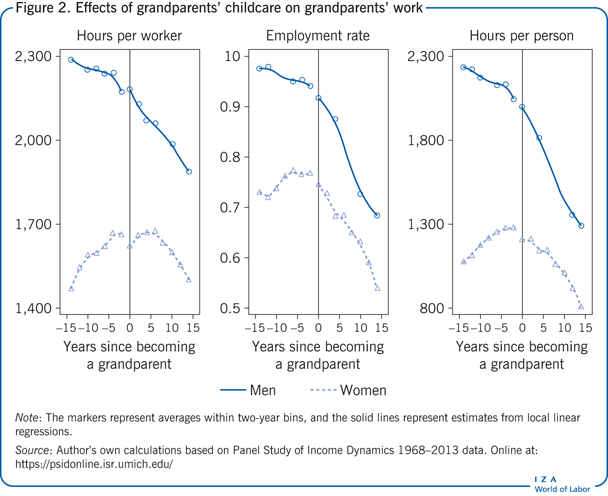

Time transfers from working-age grandparents to younger parents, in the form of grandparent-provided childcare, are substantial both in the US and Europe. These are measured by means of time diaries, a statistical tool used by agencies (e.g. the US Census for the American Time Use Survey, ATUS) that collects time-use data. Specific activities would include, for example, caring for and helping children, activities related to children’s education and health, and travel related to all of these.

For the US, the Census Bureau reports that in 2011 nearly a quarter of all children under five years old not living in the same household as their grandparents, benefited from grandparent-provided childcare, and that for 93% of these, grandparents were the primary childcare arrangement. In addition, the share of children below 18 years of age living in the same household as their grandparents was about 7% in 2010. Correspondingly, time-use data also show large time transfers, as indicated below.

One study, using the ATUS pooled 2003–2014 waves, estimates that 16% of all women and 10.8% of all men in the age range 50–64 years (grandparents and non-grandparents), report spending time in primary childcare—both household and non-household (caring for and helping, activities related to children’s education and health, and travel related to all of these). For Europe, one study estimates that the shares of grandmothers who provide regular or occasional childcare are, respectively, 22.8% and 27.8% in France, 22.1% and 18% in Germany, 26.9% and 15% in Spain, 32.5% and 9.3% in Italy. The corresponding figures for grandfathers are, respectively, 16.5% and 31.2% in France, 20.3% and 19.8% in Germany, 26.3% and 11.3% in Spain, 26.1% and 6.6% in Italy.

For individuals who report spending time on primary childcare duties, average annual childcare hours are 657 for women and 501 for men. These numbers equate to approximately 19 and 14 full-time work weeks, respectively. This picture is reasonably consistent with the one that emerges from the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS). In the HRS, individuals are asked how much time in total they spent taking care of their grandchildren during the past 12 months. Grandmothers aged between 50 and 64 years old at the time of the first interview in 1992 reported spending, on average, 816.5 hours per year. The corresponding figure for grandfathers was 346.9 hours.

Such large time transfers are very convenient for those parents who receive them, because they constitute free, flexible, highly reliable childcare that reduces the cost of childbearing and allows young parents, most notably young mothers, to remain attached to the labor market. However, because they are provided by older individuals still in their working age, they may come at the expense of the labor market supply of the grandparents themselves.

Effects of grandparents’ childcare on parents’ work

The causal effects of child rearing on parental labor supply are well understood. For instance, a review conducted for one research paper found that virtually all of the quasi-experimental evidence shows that there is a negative effect on mothers (i.e. it reduces their labor supply) in developed countries, as well as (with very few exceptions) in developing countries [4].

Given that childbearing reduces the labor supply of mothers, one would expect grandparent-provided childcare to positively affect labor force participation and the working time of mothers with young children, as the free and flexible childcare provided by grandparents mitigates such negative impact by allowing parents to keep working and/or to work more hours. Indeed, recent empirical research in economics has confirmed this. Motivated by sociological evidence that grandparent-provided childcare is provided primarily by maternal grandmothers, and is more likely to affect the career prospects of mothers (rather than fathers), one research paper used data for ten European countries from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a survey of Europeans aged 50 years and older, to investigate the relationship between time transfers from grandmothers to working-age daughters with young children on the one hand, and the labor force participation of these daughters on the other [5]. The authors measured the time transfer with an indicator for whether a woman provided grand-childcare on a daily or weekly basis, and estimated probability models in which the dependent variable is either an indicator for whether a young mother is employed or not, or a labor supply indicator that can take three values: (i) working full-time; (ii) working part-time; or (iii) not working at all. The authors found that having a mother that provides frequent childcare is positively associated with the probability that a young mother is employed, and that she is employed full-time. A further conclusion is that women’s attachment to the labor market is affected not only by their own fertility when young, but also by the fertility of their daughters when they are older. Although this correlation has no clear causal interpretation, it is suggestive of a positive effect of grandparent-provided childcare on female labor force participation in Europe.

Another study addresses the causality question more explicitly, using data from the American National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) [6]. Similar to the previous study, the authors estimate a probability model in which the dependent variable is an indicator for the labor force participation of a woman with children aged between zero and three, and the explanatory variable of interest is a variable indicating whether a grandparent (in this case pooling maternal and paternal grandmothers) provides primary or secondary childcare. Causality is addressed by using death of the maternal grandmother as a natural experiment that reduces the availability of grandparent-provided childcare. The most conservative estimate indicates that grandparent-provided childcare increases the participation rate (both full- and part-time) of young mothers in the US by about nine percentage points, which is a significant effect. The authors make the important policy point that raising retirement ages might increase older cohorts’ labor participation rates at the expense of young women’s through childcare availability [6], as grandparents may, for example, be compelled to remain in work longer because of reduced retirement benefits.

In relation to this policy point, two recent papers exploit pension reforms of minimum retirement age enacted in Italy between the 1990s and the 2000s to evaluate, in a quasi-experimental fashion, how forcing employed grandmothers to remain in the labor force for a longer period (by raising the retirement age of women) affects the labor supply of their daughters. One of the papers shows that the reform-induced increase in labor force participation of older women decreases the labor force participation of their daughters [7]. Similarly, a second paper finds that the employment rate of mothers with young children is about eight percentage points higher when their own mothers are eligible for retirement, relative to the daughters of ineligible (grand)mothers [8]. Thus, these pension reforms indicate that the availability of grandparents willing to help with childcare increases the female labor force participation of young mothers, especially in developed countries such as Italy, where the employment rate for women is low and where the formal childcare sector is thin [9].

Finally, one paper infers the effect of grandmother-provided childcare on the labor supply of women with young children in the US from the residential proximity between mothers (or mothers-in-law) and their adult daughters (or daughters-in-law) [10]. Specifically, the authors employ data from the US Census and from the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), and show that residential proximity (defined as living within 25 miles) of either one’s mother or mother-in-law, or of both, increases the labor force participation of women with children below 12 years of age by about ten percentage points, with no effect for women without young children. This asymmetry between the effect for women with and without young children suggests that the channel through which a mother or mother-in-law living nearby positively affects their daughter’s or daughter-in-law’s labor supply is grandmother-provided childcare. It should be noted though that the conclusions of this paper crucially rely on the assumption that the spatial proximity between grandmothers and mothers is as good as randomly assigned, as if it was determined by a lottery [10] —whether this assumption is valid will be discussed below. This is an important point, as randomized experiments, or random events, are necessary in order to establish causality.

Effects of grandparents’ childcare on parents’ mobility and wages

While helping young parents through labor force participation, grandparents’ childcare may hurt them in other ways. For example, through reduced residential mobility, where reliance on a specific source of childcare (in this case grandparents) makes moving far away from that source costly. The observation that grandparent-provided childcare requires living close to one’s parents or parents-in-law is the starting point of one research paper, that uses data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP). The paper finds evidence that women living in proximity to parents or parents-in-law, and enjoying grandparents’ childcare, earn lower wages and are more likely to commute longer distances to work [11]. The authors estimate that having grandparents living close by reduces wages by about 5%, while it increases commuting times by about eight percentage points.

It should also be stressed that intergenerational time transfers in the form of grandparent-provided childcare may be part of an implicit contract whereby the grandparents take care of the grandchildren and then, towards the end of their lives, will be taken care of by their children. This would reinforce the negative effect on the geographic mobility of households: not only parents need to live close to grandparents in order to benefit from their childcare activity when the children are young, parents may need to live close to grandparents also in order to honor the commitment to reciprocate and provide elderly care when the children have grown up. This possibility questions the assumption that the residential proximity between parents and their adult children is as good as randomly assigned.

Grandparents’ childcare and grandparents’ work

A counterpart of the positive effects of grandparent-provided childcare on the labor supply of young mothers must be a reduction of other forms of time use that would be available to the grandparents. Grandparents are endowed with a fixed amount of time that they can allocate among alternative uses, including work and caring for their grandchildren.

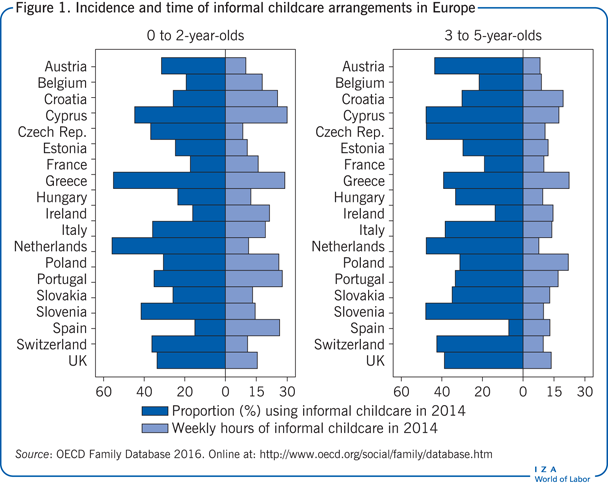

The evidence in this respect is much more scant, due to the lack of credible ways of isolating a causal effect running from grandparents’ childcare to grandparents’ own labor supply. Figure 2 shows hours per worker (by gender), the employment rate, and hours per person for people in the US who at some point of their lives become grandparents, in relation to the number of years since their first grandchild was born. Thus, for example, “5” means that a person’s first grandchild was born five years ago. In these figures, “0” is the year when the first grandchild was born, and negative numbers along the horizontal axis indicate that one is not yet a grandparent, so that, for instance, “–5” means that one’s first grandchild will be born five years into the future.

Although these figures suggest a discontinuous drop in the labor supply of American female workers when they become grandmothers (but not of men when they become grandfathers), such a before-after comparison is misleading because of the lack of a proper comparison group from which causality might be inferred. One research paper takes advantage of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a survey of US households that was initiated in 1967, which allows researchers to observe the same individuals for more than four decades. A four-decade horizon in panel data is useful in that it allows the same individuals to be observed when they are young parents and, many years later, when they become grandparents. Exploiting the different times at which the parents of girls and boys become grandparents (the parents of girls become grandparents about two years earlier than the parents of boys because women marry and have children at a younger age than men) to construct an instrumental variable for the probability of being a grandparent, they are able to conclude that becoming a grandparent causes a reduction of the labor supply of employed US grandmothers by at least 170 hours per year [1]. This effect originates among women who are already working less than full-time at the time they become grandmothers (i.e. they are somewhat marginal workers), and is stronger the younger the grandchildren are. The study also finds that the “grandparenting extensive margin” (i.e. becoming a grandparent) is much more important than the corresponding “intensive margin” (i.e. having additional grandchildren). Results indicate for these women an average reduction of about 400 hours when they become grandmothers, which declines to 350 hours when more grandchildren are born.

This estimate implies that the extent to which the large time transfers from grandmothers to their children in the form of grandparent-provided childcare, which is provided at the expense of reduced opportunity for (and supply of) work, is substantial (up to 25%). This, in turn implies a non-negligible role of grandparents’ childcare in accounting for the reduction in labor supply towards the end of the working life of women, and shows that working women reduce labor supply by about 400 hours between the age of 50 and 64 [12]. Taking this into consideration with the causal effect of becoming a grandmother on female labor supply, which was referred to earlier [1], this suggests that grandparent-provided childcare may account for one-third of the reduction in labor supply late in the working life of women in the US.

Limitations and gaps

The discussion in this contribution applies mostly to developed countries. An interesting question for future research would be the extent to which these results carry over to developing countries. It would be reasonable to expect that the results would be weaker in countries with less-developed labor markets. Also, in a developing country context, home-care of children by non-working women (mothers and grandmothers) would, in all probability, be more widespread.

Similarly, data limitations prevent, to date, an analysis for European countries similar to the one allowed by the PSID for the US economy. The reason is that studying the impact of grandparent-provided childcare on individual labor supply requires detailed longitudinal data with a sufficient time span to observe the same individuals when they are young parents and when, many years later, they are actual or potential grandparents. Collecting detailed survey data following the same families over time for several decades is an investment that pays off in the long term in terms of additional knowledge.

Finally, and perhaps most crucially, in this research area there is a lack of studies that are able to address causality, on the one hand, and welfare effects on the other. Deeper empirical and theoretical analysis is warranted to properly address these limitations.

Summary and policy advice

Evidence suggests that the availability of grandparents willing to supply childcare time mitigates the negative consequences of childbearing on the labor supply of young parents, especially mothers. However, at the same time, such childcare arrangements may reduce the mobility of younger workers and the labor supply of older workers, especially women.

The available evidence indicates that a quarter of the childcare time provided by grandparents is at the expense of labor supply for US grandmothers, while there is no statistically significant effect for grandfathers. To date, no such comparable evidence is available for European countries due to data limitations, although the surprising similarities in the grandparenting patterns in Europe (continental Europe, at least) and in the US, suggest that the effect may be similar for European grandparents.

The main policy implication of these findings is that retirement, family, and taxation policies should take into account the fact that older workers (most notably women) face a stronger incentive to reduce labor supply (i.e. a larger opportunity cost of working) after they become grandparents. This weaker attachment to the labor market is not necessarily welfare-reducing, especially if grandparents enjoy taking care of their grandchildren. Such policies could include, for example, temporary “grandparental” leave periods while the grandchildren are very young, so that the reduction in work effort by these grandparents is only temporary. Reduced labor income taxes for the elderly, to match the increased opportunity cost of time when they are grandparenting, could also be considered.

However, grandparents’ engagement in childcare may exacerbate the problems pertaining to the sustainability of pension and social security systems in developed countries. Both family and taxation policies may counterbalance the incentive for grandparents to reduce their labor supply. For example, the provision of affordable, formal childcare arrangements may help young parents to remain attached to the labor market without weakening grandparents’ work incentives. The downside of this expanded formal childcare solution is that it may have undesirable consequences for the development of the children from relatively affluent families (the marginal group that benefits, for example, from the expansion of public childcare services) relative to informal family care. Evidence that this is the case has been provided for Italy [13] and Canada [3]. Daycare has been shown in these studies to reduce the cognitive (e.g. IQ) and non-cognitive (i.e. personality) skills of children from affluent socio-economic backgrounds.

As for taxation policy, the weaker work incentives faced by grandmothers as a result of the increased opportunity cost of time, may be counterbalanced by reduced labor taxes for older women. The connection between grandparenting and labor supply therefore provides an additional rationale for an unconventional fiscal policy that differentiates labor taxation by gender, age, and, possibly, grandparent status.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here, and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [3], [12].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Giulio Zanella