Elevator pitch

The minimum wage has never been as high on the political agenda as it is today, with politicians in Germany, the UK, the US, and other OECD countries implementing substantial increases in the rate. One reason for the rising interest is the growing consensus among economists and policymakers that minimum wages, set at the right level, may help low paid workers without harming employment prospects. But how should countries set their minimum wage rate? The processes that countries use to set their minimum wage rate and structure differ greatly, as do the methods for adjusting it. The different approaches have merits and shortcomings.

Key findings

Pros

Of the numerous methods to set minimum wages, many countries now rely on an expert body to advise governments on the appropriate rate.

The “bite” of the minimum wage—the ratio of the minimum to the median wage—varies substantially across countries.

Minimum wages that vary for different groups of workers (such as by age and sector) can target low wages and poverty better than a simpler rate structure can.

The upside of government involvement in rate setting is that they can potentially take bolder steps than an evidenced based expert body but do risk politicizing the minimum wage.

Cons

Using a formula to set the minimum wage leaves little flexibility to respond to changing labor market conditions but can ensure low wage workers do not get left behind.

When the minimum wage is set by the government rather than by a formula or with the advice of a third party, there is a risk of setting it on political rather than economic grounds.

Minimum wage rates that vary for different groups of workers can be too complex to administer and may lead to non-compliance because of ignorance about the correct rate.

Comparable evidence on the effectiveness of different approaches is almost impossible to obtain, as many influences other than the minimum wage are at play.

Author's main message

The minimum wage has become an accepted way to tackle the extremes of low pay in many countries, but there is considerable variability in the way minimum wages are set around the world. Methods include formulas, government rate setting, union bargained rates, and rates recommended by an expert body. Expert bodies whose recommendations are informed by a strong evidence base have the advantage that they can respond to changing economic conditions and build consensus among businesses and workers without political interference, but they are unlikely to take the sort of bolder steps seen in the UK, Germany and other countries in recent years.

Motivation

Over 160 countries worldwide, including 21 EU member states, now have a legally binding minimum wage [1]. Alongside this increase in prevalence has come a greater appetite among both the public and politicians for ever higher minimum wages. In the UK, a recent poll found 65% of respondents in favour of increasing the minimum wage to £15 an hour, and in the US 62% favour raising the federal minimum to $15 an hour.

This public support has been recognized by politicians. The UK government has implemented significant increases in the minimum wage so that the adult rate is set to reach a target of 2/3rds of the median wage by 2024. In the US, President Biden has indicated support for a $15 minimum wage. In Europe, a number of countries including Germany, Hungary, Spain and Poland, have implemented substantial increases in the minimum wage. More broadly, a European Union Directive was passed in 2022 with the aim of promoting adequate minimum wages across the EU.

The Covid pandemic introduced a note of caution in 2020 and the subsequent surge in inflation in 2022–23 has eroded the real value of the minimum wage in many countries. But it seems that, at least for now, minimum wages are here to stay. Public support has likely been strengthened by concerns over stagnating living standards. A consensus has emerged that minimum wages, set at the right level, do not harm employment prospects. A key question is how to achieve that right level?

Discussion of pros and cons

Minimum wages have not always been so popular. Two to three decades ago, the common opinion was that minimum wages did more harm than good. The prevailing view among economists, and policymakers alike, was that minimum wages interfered with the normal workings of the labor market and priced workers out of jobs: the standard competitive model found in any textbook predicts an unambiguous fall in employment arising from the minimum wage.

This view has been challenged by more sophisticated empirical analysis and by a proliferation of labor market theories proposing that minimum wages can have ambiguous effects on employment. These theories imply that the minimum wage, set at the right level, need not result in job loss and can even increase employment by boosting the attractiveness of low-wage jobs. The first convincing empirical evidence contradicting the prevailing view came from a study of fast food outlets in the US [2]. Since then a burgeoning literature has emerged across the US and Europe and continues to inform the debate (see [3] for a review of the recent evidence). While the debate is still very much alive, the weight of evidence has shifted, and views among academics are now much more balanced [4].

Minimum wage systems around the world

Numerous methods are used to set minimum wages around the world. At one end of the spectrum, the government is in complete control of minimum wages, as at the federal level in the US. At the other end, a system of collective bargaining determines the minimum, as in Austria and, until the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 2015, in Germany. In between are a wide range of variants. Some countries use a formula for uprating the minimum, as in France, where it is closely linked to the rate of inflation. Many countries now rely on an expert body either to set the rate or to provide advice and recommend a rate to government. The UK Low Pay Commission (LPC) is a good example of the second approach, though its independence has been somewhat weakened in recent years with the introduction of a target rate for the adult minimum wage. The LPC’s role is to navigate towards the target over a period of years with limited discretion on the trajectory of the minimum wage.

The regime used to set the minimum wage conceivably has real impacts on labor market outcomes. Different regimes are likely to have different concerns at heart when deciding the rate [5]. For example, under a system of collective bargaining, unions may serve the interests of members; when governments set the minimum wage, they may be guided more by political than by economic concerns. Different minimum wage setting regimes will also differ in the degree of flexibility in responding to economic shocks. Regimes that follow a formula can result in a lack of flexibility. For example, during the financial crisis in the late 2000s, the French commission was largely compelled to raise the minimum wage in real terms despite high and rising unemployment. However, more recent experience through the pandemic has shown that many governments have taken a pragmatic approach by adjusting to labor market conditions, delaying or moderating planned increases in many cases.

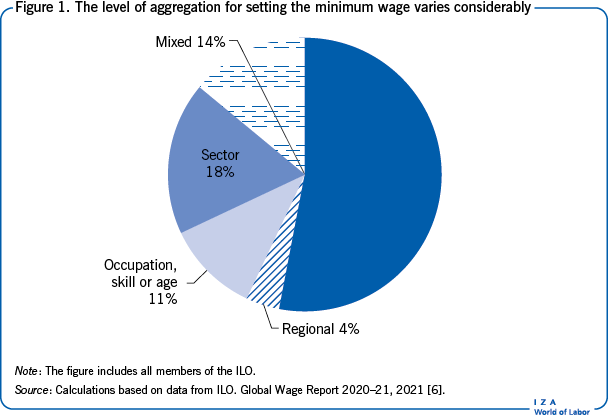

In addition to these differences in how rates are set, countries also differ in whether they use a single minimum wage or different rates for different workers. Many countries have lower rates for younger workers, though the discount varies considerably. Some countries set multiple rates, which differ by sectors, regions, and occupations (Figure 1).

When rates vary for different groups of workers, the minimum wage regime has more flexibility in responding to shocks. For example, the UK minimum wage for young workers was frozen during the economic crisis of the late 2000s, and some evidence suggests that this measure helped to maintain youth employment through the downturn [7]. The downside of flexibility is the potential for added confusion among employers and employees over which rate applies, and thus a greater potential for non-compliance.

Minimum wage setting mechanisms

Regimes involving an expert body

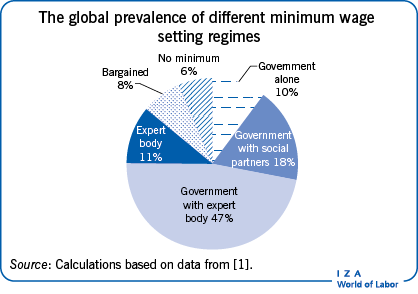

Systems with an expert body involved in setting the minimum wage are now the most prevalent. In 47% of countries, the government sets the minimum wage on the advice and recommendation of an expert body; a further 11% of countries rely on an expert body alone. Practice varies across countries, but typically this expert body includes stakeholders from the employer and employee sides and sometimes independent members.

In a number of cases the expert body is guided by a formula or target. For example, since 2016 the UK LPC has recommended annual increases towards the government set targets of 2/3rds of the median hourly wage by 2024. The LPC has three employer representatives, three employee representatives and three independent members. To inform its recommendations, they commission empirical research, take written and oral evidence from stakeholders, and visit employees and employers in the low-paid sectors across the country. The target has changed the landscape somewhat in terms of the operation of the LPC. Previously the commission had much more autonomy over rate setting, although ultimately the government would decide whether or not to accept the recommendation.

Germany introduced its first national minimum wage, at €8.50 an hour, in January 2015. Initially set by the coalition government, it is revised by a minimum wage commission that is to some extent modelled on the UK system but has only employer and employee representatives. While the commission takes advice from independent experts, contrary to the UK case, these experts do not have a formal position on the commission and do not vote on proposed changes to the minimum wage. Like the UK, the German commission do not have complete autonomy as they are guided by collectively agreed rates of pay. The Commission took a cautious approach to rate setting during the pandemic but in October 2022 a one-off intervention by the German government saw the rate increased by almost 15% to €12.00.

In Ireland, to introduce more stability to the rate setting process following the financial crisis, the Irish government set up a commission with a structure similar to that of the UK LPC, with employer and employee representatives and independent members. The Irish LPC make recommendations to the Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment on what is intended to be a fair and sustainable minimum wage. Unlike the UK system, they are not led by a formulaic approach or a target rate. The systems in Greece and Croatia follow a similar set of principles.

Government-set minimum wages

In some countries, the central government sets the national minimum wage. The most notable example of this approach is the US, where Congress votes on changes to the minimum wage. The US has tended to change the federal minimum wage infrequently, with changes depending largely on the political balance of power at the federal level. The federal minimum has not been uprated since July 2009 and sits at $7.25 an hour. This inaction has resulted in a proliferation of states and cities increasing their rates beyond the federal level. Some 30 states now have rates set higher than the federal level. The Biden administration has proposed raising the federal minimum to $15 an hour but so far this rate only applies to firms in receipt of government contracts.

Formulaic approaches

Other countries follow a rule or formula for fixing the minimum wage. In France, the interprofessional minimum wage (“salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance”) is tied to the consumer price index and uprated annually. In the aftermath of the economic crisis of 2008–2009, the French government established an advisory board of experts. Although bound by the formula, the board may recommend increases higher than those implied by the consumer price index. This “top up” was used for the first time in 10 years in 2021 to keep pace with higher inflation. Luxembourg also links the minimum wage to consumer prices, and the Netherlands links the minimum wage to average wage growth, although a system of bargaining allows for some flexibility.

The recent surge in inflation has resulted in declines in the real value of the minimum wage in many countries and has renewed attention on these formulaic approaches that link the minimum wage to prices or wages [8]. Often these are somewhat backward looking as they link to past measures of the price index, leaving a lag before the real value is restored. A number of countries, including Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, have implemented more frequent upratings in order to maintain the real value through this period of high inflation.

Collective bargaining

The influence of trade unions and other employee organizations varies considerably across countries. In some countries (largely in Europe), minimum wages emerge from bargaining between employers and employees. These minimum rates are often agreed at the sectoral level, which can result in multiple minimum wages. In countries with collectively agreed minimum wages, coverage can be high. Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, where more than 90% of workers are covered by one of the sectorally agreed minimum wages, are good examples of this approach.

The “bite” of the minimum wage

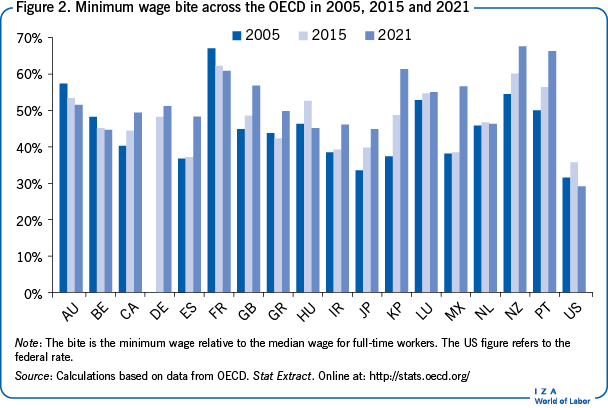

The “bite” of the minimum wage—the ratio of the minimum wage to the median wage— measures the relative importance of the minimum wage in each labor market. For many countries, the minimum wage is set at around half the median wage (Figure 2). But it varies considerably—from under 30% in the US to more than 60% in France and New Zealand. The UK has been gradually pushing up the relative value of the minimum wage over the past decade; to reach a peak “bite” of 58% of full-time workers median pay in 2020. In New Zealand, the minimum wage has also been significantly increased and is now over 67% of the median wage. Even in countries where minimum wages have been reduced or frozen in recent years, as in Greece and Ireland, the relative value has bounced back more recently.

The national bite statistics shown in Figure 2 disguise variations within countries by region, industrial sector, and age groups—variations that can be larger than the variation across countries. In the UK, the bite varies significantly meaning that just 3.4% of workers in London are paid at the minimum wage compared to over 7.5% in the North East and 8% in Northern Ireland [9]. These regional differences in wages periodically lead to calls for regional variation in rates. Indeed, in the US numerous states and cities have rates that are significantly above the federal minimum. The “bite” of these minimum wages varies considerably due to large differences in average pay. For example, the bite is just 45% in San Francisco compared to 75% in Los Angeles despite the rates being similar ($16.99 compared to $16.04) [10].

Variations in legislated minimum wages across groups of workers

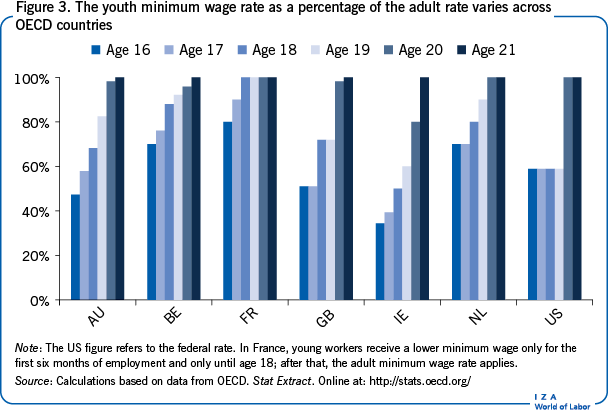

Many countries have lower minimum wage rates for younger workers on the premise that they are, on average, less productive than older workers and that spells of unemployment in the early years of work can have long-term scarring effects. Indeed, some countries exempt young workers from coverage completely. On the other hand, fairness considerations have led to some countries abandoning youth rates and in recent years there were reductions in the age threshold at which the adult rate is paid in a number of countries.

As such, the minimum-wage treatment of young workers differs considerably across countries (Figure 3). The Netherlands sets relatively low minimum wage rates for young workers: less than 60% of the adult rate for those aged 18 and 19. The age at which the full adult rate applies has been reduced from 23 to 21 in recent years. A similar reduction in eligibility can be found in the UK where the threshold for the National Living Wage has fallen from 25 to 23 and is set to drop to age 21 by 2024, resulting in a simpler age structure.

In France, Portugal, and Spain, the minimum wage rates for young workers are relatively high, which has led some to link this to high youth unemployment in those countries. At almost 30% in Spain, 20% in Portugal, and 17% in France, youth unemployment rates in these countries are somewhat higher than the EU average of 14% in 2023. A few studies have found negative employment effects from minimum wages for young workers [11]. But obtaining direct evidence that higher youth minimum wage rates result in youth unemployment is difficult because opportunities for robust evaluation are few and far between.

Some of the most robust evidence on the effects of the minimum wage on youths comes from New Zealand, where eligibility for the adult minimum wage was lowered from 20 to 18 in 2001, resulting in a 69% increase in the minimum wage for 18- and 19-year-olds. But there were no robust changes to employment or work hours for this group [12]. Similarly, the recent age reduction in the UK was the subject of a report for the LPC that could find no detrimental impact on employment of 22- and 23-year olds [13].

Many countries take a cautious approach to youth minimum wages given the uncertainty about employment impacts and weaknesses in the minimum wage as an anti-poverty tool. The link between low wages and poverty is weaker for young workers than for older workers since many, although not all, low-paid youth may be living at home in middle-income households. Another downside of tying the youth and adult rates together is that it can result in a lower adult rate than otherwise. This is particularly the case where the minimum is set as a proportion of the median or average wage.

Despite wide regional variation in wages in most countries, only four countries have nationally set minimum rates that vary by region: Canada, China, Indonesia, and Japan. Of course, there are regional variations in minimum wages within some countries as a result of rates set by local jurisdictions, such as those set by US states. Here, 29 states plus the District of Columbia (DC) have rates above the federal minimum, mostly located in the east and west of the US. DC has the highest rate at $17, more than double the federal rate, but many cities have higher rates still. The UK has recently heard calls to introduce a regional minimum wage, particularly for London. But the downside of such arrangements is a loss of simplicity in the rate and potential issues around the borders where minimum wage rates change. There are also concerns about cementing regional labor market differences, with the lower-pay regions being left behind [8].

Minimum wages can vary by sector of employment, often in conjunction with collective bargaining to determine them. In countries with a minimum wage system, about half set the minimum at the national level, and half at the sectoral (or occupational) level [1]. The use of sectoral rates is more prevalent in Africa and Latin America than in OECD countries. The advantage of a sectoral minimum is that it can raise the pay of more workers since it can better target low pay in each sector. But sectoral minimum wages can also result in a lack of coverage for large sections of the workforce [14]. In addition, sectoral or occupational rates can add complexity and result in myriad rates for each industry. The wide-ranging use of sectoral rates in Latin America is thus often cited as a reason for high non-compliance there.

Merits of the different approaches

Most economists and policymakers have concluded that a minimum wage, set at the right level, can have positive effects on the labor market. In countries with strong in-work welfare systems, it can shift some of the costs of raising incomes in poorer households from government to firms. It can also tackle fairness in the labor market, which probably helps explain why the minimum wage is so popular with the public.

Too little evidence to assess them

But which minimum-wage system best delivers these outcomes without unduly diminishing the employment prospects of affected workers? The key variables here are the minimum wage setting regime, the degree to which rates vary across subgroups of workers and the frequency of increases. There appears to be no direct empirical evidence on labor market outcomes of different minimum wage setting systems, likely because of the difficulty of comparing differences across countries where many other labor-market practices differ.

But there is some evidence on the effect of variation in rates by groups of workers. That evidence tends to show that where young workers are paid the same as adult workers, they can potentially suffer higher unemployment. Variation in the minimum wage by age appears to be a promising way to use the minimum wage to tackle poverty while protecting more vulnerable workers. A higher minimum wage rate for older workers would be a better targeted poverty tool, since low-paid older workers are more likely to be living in poverty than low-paid younger workers. Some variation in rates is therefore desirable as it allows for a more flexible minimum-wage system that can better target low pay and poverty.

In addition, having a complex set of rates can reduce compliance with the legislation because of increased confusion among employers and employees. There is some indication that the somewhat complex structure of rates for apprentices in the UK, although still relatively simple, has resulted in a high level of non-compliance.

Another dimension of minimum wages that has some political and public support is variation across regions within countries. Witness the proliferation of rates across the US as states and cities break free from the federal minimum; calls for a higher minimum wage in London than in the rest of the UK; and proposals for regional variation in Germany. As regional flexibility gains support, there is also increasing support for an EU-wide minimum which would likely be set in relation to average wages in each country.

Expert bodies as the preferred minimum wage setting mechanism?

Support has been growing in many countries for a system of setting the minimum wage in which an expert body advises the government. Often this is within the context of a fixed formula or target for the minimum rate. For many years this was how the UK LPC operated. This arm’s-length approach is used in many areas of policy. Examples in the UK include the Monetary Policy Commission which set interest rates and the various public sector pay review bodies that recommend pay increases across the armed forces, teachers, nurses, etc. These expert panels depoliticize the process by providing evidence based on economic fundamentals in place of politically driven decisions.

An expert panel can also ensure buy-in from all stakeholders in setting policy. This is crucial for policies such as the minimum wage, where there can be clear differences in the benefits and costs to employers and employees—and thus opposing views on what the rate should be. How the expert panel is formed is also crucial. Different approaches have been adopted, with varying use of independent panel members, with or without voting rights. South Korea’s minimum wage commission is composed of nine employers, nine employees, and nine independent members. The structure of the panel and the fact that discussions are made public have affected its ability to agree on rates. The commission needs enough flexibility to respond to economic shocks so that the minimum wage does not hurt employment or low wage workers do not get left behind. That means that it must have the authority to act without political interference or hard constraints on what it can recommend.

There are also downsides to having an independent, evidence-based body. The UK LPC is very careful to assess the impacts of the rate changes it recommends. This is achieved through a number of means including analysis of labor market data and commissioning academic research. As a consequence, the recommended increases have tended to be somewhat cautious at times, taking small steps and then assessing the outcome. The bold changes instigated since 2016 with the introduction of targets for the minimum wage could only really have been implemented through political will, especially as there was an acceptance by government that they would likely result in some job loss. The pre-2016 LPC is unlikely to have implemented such changes, which seem to have led to an impressive reduction in the number of low paid workers without any significant impact on employment.

Limitations and gaps

The evidence for what type of minimum wage setting regime works best is very difficult to evaluate empirically. Regimes generally vary only across countries, so any empirical analysis is essentially a cross-country analysis. The disadvantage is that many other country-level influences are likely to be at play that are correlated with minimum-wage policy, such as policies toward in-work benefits and union bargaining. That makes it very difficult to distinguish the effect of the minimum-wage regime on outcomes for low-paid workers from the effects of all these other influences.

A similar concern applies when trying to understand the use of different rates for different groups of workers, though this evidence is a bit more robust given the natural experiments made possible by policy changes in the minimum wage rates that apply to different groups. An example is New Zealand, which lowered the age at which the adult rate applies from 20 to 18. Another are the sharp reduction in age of eligibility in the UK from 25 to 21 in the space of a few years.

Summary and policy advice

Minimum wages have become an accepted part of the anti-poverty policy landscape in many countries and are now widely implemented to tackle the extremes of low pay. How minimum wages are set varies considerably, but the use of expert bodies coupled with a formula or target to advise governments on rates is increasing. Similarly, the use of different rates for different groups of workers varies; some countries have very simple structures with just a few rates for different ages, and some have very complex structures with a multitude of rates.

What level of minimum wages works best depends on the context. Each minimum wage should be tailored to its specific labor market setting. Labor markets can vary substantially, with differences in the extent of low-paid workers, in the levels of formal and informal work, and in the ability to enforce labor regulations. Any minimum wage regime has to accommodate these different features in a sensible way.

The structure of minimum wage rates is also context-specific. However, there appear to be general merits in a relatively simple structure. Age variation can help to target low pay and poverty more precisely. But a complex set of rates can lead to confusion and lower compliance.

Finally, who should set the rate? The growing prominence of expert bodies that advise governments is an indicator of the success of this approach. An expert body that weighs the evidence before making recommendations can guide minimum wage policy through both good and bad economic times. One limitation of such an evidenced-based body is political: it is unlikely to make stepwise changes to the level of the minimum wage, as with the new higher rate set by the government in Germany and the higher rates implemented by the UK government. These bold initiatives appeared to have been a success but there is a question as to how far minimum wage policy can go. Formulas and targets may ensure that low wage workers don’t fall behind but expert bodies bring with them evidenced based flexibility. One can maybe expect to see this type of mechanism that combines expertise with a set of guiding principles gaining further ground as more countries take a bolder stance with their minimum wages.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates data and figures, it adds discussions on recent developments, the impact of Covid-19 and increasing inflation. It adds new Key references [3], [6], [8], [9], [10], and [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Richard Dickens