Elevator pitch

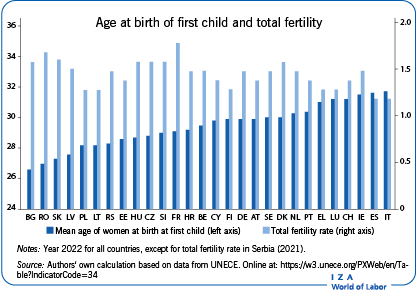

Increasing population age and low fertility rates, which characterize most modern societies, compromise the balance between people who can participate in the labor market and people who need care. This is a demographic and social issue that is likely to grow in importance for future generations. It is therefore crucial to understand what factors can positively influence fertility decisions. Policies related to the availability and costs of different kinds of childcare (e.g. formal care, grandparents, childminders) should be considered after an evaluation of their effects on the probability of women having children.

Key findings

Pros

Increased availability of formal childcare is associated with higher fertility rates, particularly for first births.

Reducing childcare costs can significantly boost fertility rates by making child-rearing more affordable.

Grandparents play a crucial role in childcare, positively influencing both maternal employment and fertility.

Formal childcare is associated with positive effects on children’s cognitive and non-cognitive development, supporting its promotion.

The availability of immigrant childminders can increase fertility among highly educated women by reducing childcare burdens.

Cons

Maintaining high-quality formal childcare is expensive, which can limit its availability and accessibility.

Variation across different geographic contexts makes the relationship between childcare availability and fertility ambiguous.

The lack of comprehensive data on the availability and costs of childminders makes it difficult to assess their impact on fertility decisions.

The reliance on grandparents for childcare introduces significant endogeneity problems, as the decision to use grandparents’ care is often internally determined within families.

Better childcare availability may lead women to work more, which could paradoxically reduce their likelihood of having more children.

Author's main message

The availability of low-cost childcare should reduce the cost of child rearing and therefore have a positive effect on fertility. Indeed, there is empirical evidence that shows a positive link between childcare availability and prices and families’ fertility decisions. However, some types of childcare are accessible only to certain families due to relatively high costs (e.g. childminders or private formal care) or because of family characteristics (e.g. proximity to and age of grandparents). It is therefore important to expand childcare possibilities to all parents via publicly funded childcare.

Motivation

Fertility decisions are taken at the individual/couple level and may be influenced by the social relationships and networks to which individuals belong as well as the prevailing institutional and cultural setting in which they live. Comprehensive availability and/or low cost of childcare should make having children easier for parents, and therefore have a positive effect on the decision to have a child [1]. In examining this topic, it is useful to distinguish among different types of childcare: care provided by parents, care in formal childcare centers, care provided by childminders and relatives (especially grandparents). These forms of childcare are characterized by different availability and costs. Formal childcare may be publicly or privately provided, with the differences being related to the required fees and families’ probability of access; professional childminders may be available with higher costs compared to other modes; finally, grandparents may represent a flexible and cheap childcare option, but only if grandparents are in good health, not in employment, and geographically close. Aside from the availability and cost of childcare, other aspects, such as preferences, trust (toward institutions, other people, and one’s own family) and the quality of childcare may also influence fertility rates.

Discussion of pros and cons

Formal childcare

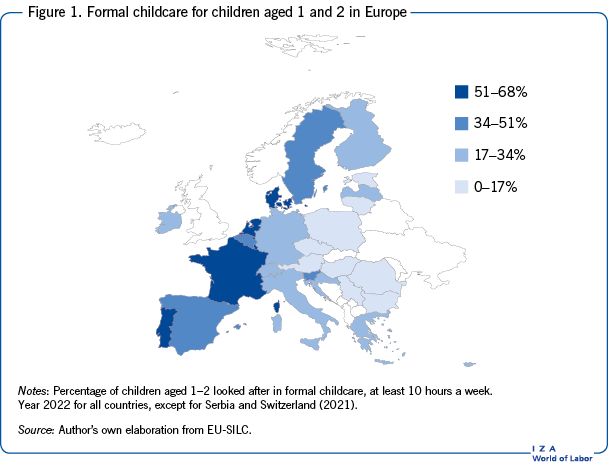

Several studies have considered the relationship between formal childcare and fertility. With respect to other types of childcare, there is a substantial variation between different geographical contexts. In the US, formal childcare is typically private, with most research and debate addressing prices and quality. In Europe, by contrast, formal childcare is mainly public and the debate addresses its availability (rationing of the service versus universal provision). Moreover, within the EU, there is substantial variation in childcare use across countries. For instance, in Hungary around 5% of children aged 1−2 are looked after in formal childcare centers for at least 10 hours per week; the corresponding number in Denmark is more than 65% according to data from the 2022 EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (Figure 1). The non-universalism of formal childcare in many countries is related to the high costs of maintaining small class sizes (i.e. few children per teacher/caretaker).

Notwithstanding the diversity of EU countries, a positive correlation is generally found between public childcare coverage and the probability of having a child.

The most common strand of studies examines the relationship between fertility and the local availability of childcare (in the EU) or childcare prices (in the US), taking into account mothers’ work decisions. Information on childcare characteristics is usually collected through surveys and aggregated to build average indicators at the local level. Several European studies show that fertility is higher in those regions where the availability of formal childcare is highest. On the other hand, US studies provide results suggesting that lower childcare costs increase fertility. Results are obtained by comparing how transitions between employment (including job-to-job as well as moving in and out of employment) and fertility rates respond to geographic variation in weekly childcare expenditures, and how variation in the individual-level association between fertility and labor market participation is explained by conditions in the local childcare market.

Given that childcare is typically private in the US, prices and availability are determined by parental demand and market supply and therefore influenced by internal factors (endogenous). In this sense, the US studies have drawbacks. Similarly, in the European context, where childcare is provided by the public system, the assumption that coverage is influenced by external factors (exogenous) is questionable. Unobserved local factors that affect fertility decisions are also likely to affect the local availability of childcare, leading to an overestimation of the true effect.

These limitations can be overcome when researchers have access to data on the geographical availability of childcare over time. This allows one to consider local characteristics, which do not vary over time, that can affect both childcare availability and fertility (e.g. cultural factors, employability of women, preferences to have large families). This is the case of studies carried out with data from Norway [2], Belgium [3], Germany [4], and Japan [5]. Following this strategy, these studies find a strong positive effect of childcare availability on fertility.

The size of the effect is also relevant: for Belgium, for example, research finds that a 10% increase in formal childcare availability leads to a 16% higher chance of first birth. These types of results are achievable because Nordic countries have very good data at their disposal: the availability of register data for the whole population over time allows researchers to analyze large samples and not lose precision when using more sophisticated analytical strategies.

With respect to prices, there is evidence from a study which exploits the introduction of generous daycare subsidy policy in an Italian region, and finds that reducing the cost of kindergarten has a positive effect on the likelihood of having a child, even if quite small [6].

A final important aspect, more recently highlighted in the literature, is that attending formal childcare (compared to other forms of care) positively affects child's cognitive and non-cognitive development.

Grandparents

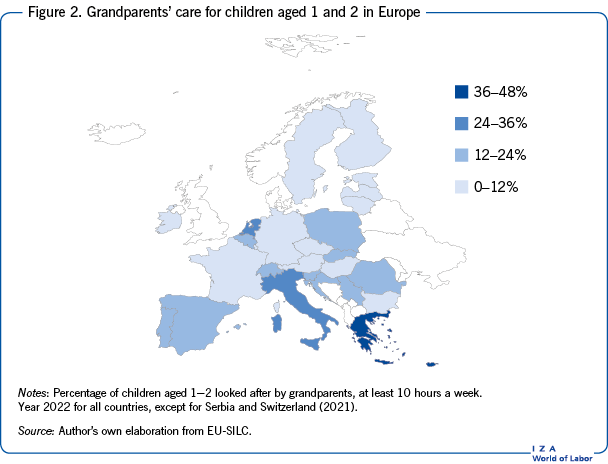

The availability of grandparents willing to care for grandchildren should decrease the cost of child rearing and therefore have a positive effect on fertility. However, different aspects need to be considered, such as grandparents’ age and health. Sick or frail grandparents may be willing to help with childcare, but might not be considered reliable enough by parents. Younger grandparents may be less available because they are still at work. Finally, the role that grandparents take in childcare may vary according to a society’s welfare system and culture. Grandparents seem to be more important in those countries where state-provided welfare is weak. According to EU-SILC data the percentage of very young children (1−2 years old) in Europe who are looked after by their grandparents for at least 10 hours per week ranges from less than 3% in Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden—where welfare systems are strong) to more than 25% in countries like Italy, Greece, and Cyprus, where welfare systems are not robust (Figure 2). Countries with a high percentage of grandparents helping in childcare are typically those with lower fertility rates .

Most studies that address this topic focus on the impact of grandparents’ care on mothers’ work decisions, and typically find a positive relationship [7]. More recently, a few studies have also considered the impact of grandparents’ care on fertility. The researchers examine how the probability of having a child changes based on the care provided by grandparents. This method is straightforward and direct when considering births subsequent to the first: they estimate the impact of receiving help in caring for the first child on the likelihood of having an additional child [8]. However, estimating the effect on the birth of the first child is more complex. In this case, the probability of receiving help is predicted by analyzing variables related to the couple and the distance from their parents' (the grandparents') home [9]. Other studies, instead, directly estimate the effect of the distance from potential grandparents' homes on the probability of having a child [10]. All these studies consistently find a positive effect of grandparents' availability on the couple's fertility.

Moreover, the extent to which grandparents can help care for grandchildren depends on the grandparents’ past fertility behavior. In other words, if grandparents have multiple children, who then have multiple children of their own, then the grandparents’ availability to provide childcare may be reduced across the group of grandchildren. This implies that the more siblings a parent has (and the more children each sibling has), the lower the chances that an adult child will receive childcare help from their children’s grandparents. One study does find that an adult child is more likely to have another child if his/her sibling receives childcare help from the grandparents; but this is true only when the grandchild being looked after is older than three. In contrast, adult children are less likely to have another child when grandparents look after a sibling’s child who is younger than three [11].

However, it should be noted that the above studies do not fully address one important endogeneity problem: the use of grandparents’ care is decided within the family and not determined exogenously. One exogenous shock that has been utilized to establish a causal link between grandparents' help and fertility is the health of the grandparents. Studies have shown that the presence of relatively young and healthy grandparents (serving as a proxy for their availability and reliability) positively influences fertility [12]. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that even the mere existence of a living grandparent has positive effects on fertility [13].

A final interesting finding relates to the effects of grandparents' care on the development of their grandchildren. Children looked after by grandparents tend to have a better vocabulary, likely due to the one-on-one or even two-on-one grandparent-child interaction. However, this benefit is observed only in families with an advantaged socio-economic background [14].

Childminders

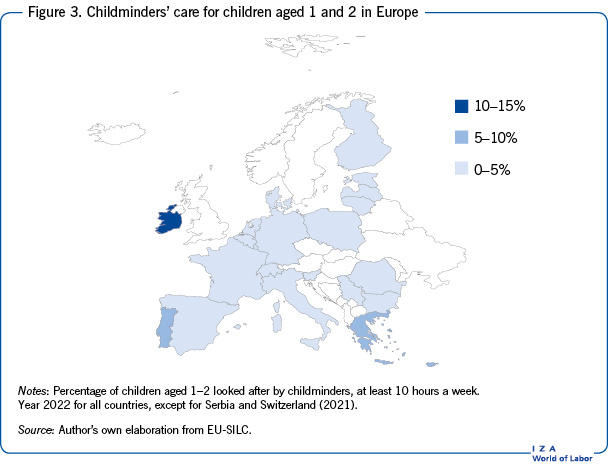

There is less research on the effect of childminders’ availability and costs on fertility decisions than for other modes of childcare. One reason is that the percentage of young children looked after mainly by childminders is relatively small, given that few families can afford to pay the full wage of a person to look after their child. In most countries, less than 5% of children are looked after primarily by childminders. One exception is Ireland, where, as EU-SILC data show, the percentage equals 13% (Figure 3). Despite the relatively low levels of childminder care, a positive association between childminders’ diffusion and fertility rates can be observed at the country level.

A second reason for the lack of empirical evidence on childminders is a lack of data on their labor supply and salaries. One exception is found in the immigration literature because a large share of childminders are immigrants. While there is much concern about the potentially negative impact of immigration on natives’ employment, less attention has been paid to the potential benefits of immigration on native women’s labor market participation and fertility. However, simply relating the presence of immigrants to women’s fertility and work decisions might not reveal a causal relationship if immigrants are more likely to reside in places where women already work more (in more developed regions, for example) or in areas with typically large families. To address this concern, researchers exploit the fact that new immigrants are more likely to live in areas with high historical concentrations of immigrants from the same country of origin, and show that there is indeed a positive effect of new flows of immigrants on both fertility and work of native women. Given that childminders usually cost considerably more than formal childcare, these effects are driven by highly educated women [15].

Limitations and gaps

In general, most of the past studies were limited by a lack of adequate data and because they use methods that cannot establish causal relationships between childcare and fertility. Studies looking at the relationship between the use of external childcare and fertility cannot be established as causal because women who use external childcare may have other unobservable characteristics that also affect the decision of having a child. For example, women who are more trustful, in general, may have more positive attitudes toward externalizing childcare, and toward having more children. In studies exploiting the local availability of external childcare, the reason for which there is more external childcare in a given region can be related to the respective families’ preferences. In studies looking at the effect of grandparents’ availability to provide childcare, the endogeneity problem could be quite severe. First, families who can and do choose grandparents as their main childcare option may be rather different from other families in terms of family decisions. Second, from a methodological point of view, the use of grandparents’ childcare is not determined outside the family (e.g. as with public childcare or immigrant flows).

More recent studies, however, have overcome these limitations. In fact, there are now more studies available that exploit data on the availability of external childcare over time, thus allowing for the consideration of local characteristics that do not vary over time. However, for the correct determination of causal effects, large sample sizes are required to produce precise estimations and to allow for the study of heterogeneous effects across different subsamples of the population; such large samples are less common, especially in Southern European countries, where concern about low fertility is very high.

Another consideration related to the women’s work dimension is that women who are more likely to change their fertility intentions in response to childcare availability are probably those who want to work. One may expect stronger impacts on fertility from the availability of (low-cost) childcare in two (almost opposite) cases: for women who are more career-oriented, as well as for women who need more income. Moreover, there is a lack of data and evaluation regarding the combination of work-life balance tools that are not yet officially recognized as childcare but could have beneficial effects. For instance, full-time schooling followed by access to extracurricular activities.

Summary and policy advice

Theoretical models predict that a larger availability of childcare and reductions in childcare costs should affect both the labor supply of mothers and the fertility of couples. By lowering the cost of having children, the demand for children should, theoretically, increase. However, the effect of childcare on fertility is likely to depend on the mother’s labor supply decision (i.e. does the mother wish to work more or have more children), so that the link between childcare and fertility remains an empirical issue. A number of empirical studies look at the relationship between different modes of childcare (formal childcare, childminders, grandparents) and fertility decisions. There is evidence of a positive impact of childcare availability on the probability of having children.

To answer the question of what types of childcare should be promoted in order to increase fertility, it is necessary to account for the costs and benefits of each childcare mode for different kinds of families. While grandparents’ care is the cheapest option, it is not available to each family. In some countries, like Italy and Germany, policymakers have actively encouraged grandparents’ care as the main means of childcare. However, this type of policy, if not accompanied by other measures, cannot be very effective. First, grandparents (probably grandmothers) need to be retired to provide primary childcare, which stands in contrast to many new reforms aimed at increasing the retirement age in most European countries. Second, because grandparents’ care may be less available when grandparents have multiple grandchildren from more than one adult child, this form of childcare may thus be more effective in countries where families are typically smaller, i.e. in countries with low current (and future) fertility.

While public childcare seems to be the most effective policy for all families, it is important to consider its high costs. Therefore, it is necessary to offer a variety of services (such as flexible hours, proximity to workplaces, and coverage during summer periods) and adjust fees based on family circumstances.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous referee(s) and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of this article updates figures, pros and cons, extends discussion e.g. on formal childcare and grandparents, and adds new Key references [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [8], [9], [10], [12], [14], and [15].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The authors declare to have observed these principles.

© Chiara Pronzato, Sharon Picco, and Stefania Ottone