Elevator pitch

Compared to developing economies, European transition economies had high levels of human capital when their transitions began, but a lack of resources and policies to protect poor families hampered children’s access to education, especially for non-compulsory school grades. Different phenomena associated with transition also negatively affected children’s education: e.g. parental absence due to migration, health problems, and alcohol abuse. These findings call for a greater policy focus on education and for monitoring of the schooling progress of children in special family circumstances.

Key findings

Pros

Human capital development is crucial for economic growth and poverty reduction since it reduces intergenerational transmission of economic status and increases the probability of escaping poverty.

Human capital development depends on public and family investment in children’s education.

During the early years of transition, south-east European and former Soviet Union countries had higher stocks of human capital compared to developing economies.

Access to education was universal during the socialist period.

Cons

Enrollment rates in pre-school and secondary school have dropped sharply in many transition economies.

Poor families have been disproportionately affected by changes in the educational systems of transition countries.

Real expenditure on education has fallen in most transition countries.

Parental health shocks due to economic transition or civil wars have negative impacts on children’s schooling achievements.

Parental absence due to temporary migration is negatively associated with school attendance.

Author's main message

Children’s educational achievements and the equality of the opportunities available to them have been negatively affected by the transition from centrally planned to market economies, due to governments’ tendency to neglect educational expenditure. School dropout rates are associated with other factors closely related to the transition process, such as parental migration and health status. Policymakers in south-east Europe and the countries of the former Soviet Union should thus promote educational opportunities and improve the quality of their education systems. They should encourage school attendance for children with special family circumstances, such as when parents live far away or suffer from health issues.

Motivation

The transmission of human capital across generations is of great importance for social scientists and policymakers since it is a key factor for growth, poverty, and inequality. Investment in education pays off in terms of future earnings and stimulates intergenerational mobility. A child’s educational success depends on its parents’ decision to invest in its education, on the quality of education supply, on family background, and on family circumstances.

When the transition from planned to market economies started in south-east Europe and the former Soviet Union (FSU), the human capital inherited from the socialist period was high compared to other countries at similar stages of economic development [1]. However, many transition governments did not maintain this positive feature, allowing the human capital advantage to dissipate due to weak public investment in education [1], [2], [3], [4]. Several studies show that different household-level shocks further hampered children’s educational success, forced children to drop out of school [3], [5], [6], [7], or increased their probability of suffering from depression or other health problems [8]. Transition shocks also reduce the presence of parents in the household and the time they are able to devote to their children [9].

Discussion of pros and cons

Education in south-east Europe and the countries of the former Soviet Union

A significant drop in enrollment, especially in secondary school, has been observed in south-east Europe and the countries of the FSU as a result of their transition to market economies over the past 30 years. This drop can be attributed to supply and demand effects. For example, transition and associated civil disruption caused numerous problems for the respective education systems: destruction of school buildings, unstaffed schools in rural areas, and corruption triggered by inadequate salaries for teachers [3]. The overall quality of education decreased and rural areas in particular suffered from an insufficient number of pre-schools and secondary schools. As a result, the opportunity cost (a benefit that a person could have received, but gave up, to take another course of action) of education increased for those families that were negatively affected by transition shocks [1]. Non-compulsory education (pre- and secondary schooling) became especially costly for these “new poor” households and education inequality became a main concern for society.

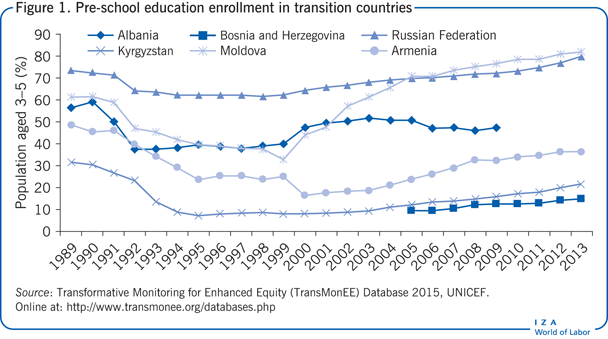

Transition governments did not consider pre-school education a priority; they thus allocated only marginal resources to the pre-school level within their education budgets. The situation was especially difficult for rural communities that had limited access to pre-school systems due to this underfunding; this disadvantage was further compounded by myriad infrastructural problems. Figure 1 shows trends in pre-school enrollment of children between three and five years old in six transition countries. A clear decline can be observed during the 1990s, which Moldova, Russia, and Armenia began recovering from in 2000. In the other countries, pre-school enrollment rates stabilized at very low levels, from 10% in Kyrgyzstan and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) to 50% in Albania.

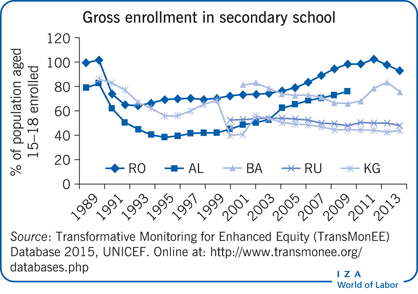

Primary education received the most attention from government during the transition; however, the average quality of primary school education was poor during this period and unequal in terms of learning achievements, between urban and rural areas as well as different socio-economic backgrounds [3], [9]. Education policies have only weakly focused on educational outcomes; they have largely kept antiquated curricula and low standards of pedagogy. Most people in the 15–24 age group were negatively affected by transition changes while at school. In the early transition period, public budgets declined and governments allocated more resources and policy efforts to maintaining basic compulsory schooling, usually at the expense of pre-school and upper secondary levels [10]. As a result, many countries observed a high percentage of secondary school dropouts (Illustration, [1], [10]).

Educational inequality also increased in upper secondary and other non-compulsory levels of education, due to the absence of specific programs to support poor families [1]. In principle, pre-school, basic education (including textbooks), secondary education, and school transport were free of charge for all households, but, unfortunately, scholarship distribution tended to be very regressive. In the Republic of Macedonia, for instance, the secondary school enrollment rate was 84%, while among poor families it was only 67% for girls and 65% for boys. Moreover, focusing on the poorest decile of the population, secondary school achievement was significantly lower [10], which hampered the skill formation of poor children, whose return to schooling would have been an important opportunity to escape poverty.

Public expenditure on education has been inadequate to improve educational outcomes and equity

Research clearly shows that children have not generally benefited from the economic recovery in the early and mid 2000s as much as other parts of the population, and child vulnerability is concentrated among certain groups and geographical areas.

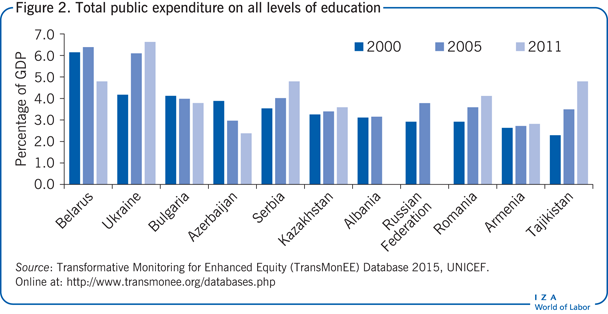

Prior to transition, south-east Europe and the FSU socialist countries provided free education at all levels and in all geographical areas; they also subsidized meals, school materials, and uniforms. With declining public expenditure on education and rising input costs, a slow process of redefining what governments could and could not provide has occurred [10]. While there is considerable debate about what policies could be implemented to improve the situation, there is relatively broad agreement that education systems in south-east Europe and the FSU have only weakly focused on educational outcomes and equity. Governments did not allocate a sufficient proportion of their state budgets to education (see Figure 2), especially to non-compulsory levels, and there were no other subsidies that successfully supported families with children [2].

Figure 2 ranks several transition countries according to their share of GDP allocated to all levels of education in 2000, 2005, and 2011. Belarus, one of the poorest countries in the region, reports the highest level of expenditure as a share of GDP—over 6% in 2000—followed by other poor countries like Ukraine and Bulgaria. At the other end of the spectrum, the Russian Federation, Romania, Armenia, and Tajikistan reported expenditure levels of less than 3% of GDP in 2000. In 2005, during the recovery period, public expenditure on education was lower than 4% in the majority of the countries. For them, expenditure in education increased between 2000 and 2011, with Ukraine exhibiting an especially large increase. However, some countries still allocated a very small share of their national income to education in 2011. During the growth period in the 2000s, many countries substantially prioritized education in their budget. However, despite rapid growth rates, some of them, like Kazakhstan, maintained an almost constant share during the observed period. Reaction to the recent global economic crisis has also been heterogeneous, with some countries reducing education expenditure (e.g. Belarus and Azerbaijan) and others maintaining their prioritization of investment in human capital (e.g. Ukraine, Serbia, Romania, and Tajikistan).

Transition countries have failed to produce policies that target children in need of special treatment, such as those growing up in incomplete families. Findings on Albanian [3] and Romanian [8] children, for instance, call for public authorities to pay greater attention to children of migrant workers. Policymakers should consider the fact that, even if migration is an important source of economic growth for the country thanks to remittance inflows, there can be long-term costs associated with the loss of human capital due to the distance between parents and children, which can have serious consequences for future living standards. As such, children’s school attendance should be properly sustained, with adequate instruments designed to compensate for the absence of parental guidance in those households where one or both parents have migrated abroad.

In contrast to other regions, where policies targeting children’s schooling have been extensively implemented, south-east European and FSU countries did not implement any specific programs targeting families with children or aimed at reducing school dropouts during the 1990s and 2000s. The only exception is Macedonia’s Conditional Cash Transfer for Secondary School Education, which was implemented at the end of 2010.

Educational equity is also worsened by widespread corruption in the distribution of subsidies and services. Since the collapse of communism, there has been a steady growth in bribe-taking behavior by state officials. State employees in the health and education sectors, and those dealing with services or benefits provided by the state in general, frequently demand bribes for inclusion in public programs, medical treatments, and schooling progression [2].

The transition period also brought unexpected family problems and hampered families’ ability to care for, support, and protect their children when families experienced unemployment, low income, divorce, disability, or illness. The resulting family shocks, often associated with or exacerbated by an increase in alcohol consumption, drug abuse, or violence at home, reduced the quality of the family environment and in some cases led to the removal of children from their homes by the state. Among the high share of children placed in formal care institutions during transition, most of them were deprived of parental care simply because their families could not afford to care for them [10].

Children’s education and parental job displacement

In many countries, the transition to market-oriented systems involved a complete restructuring of the economy, and, in some cases, the birth of brand new nations, often emerging as a result of civil wars. These radical changes induced a large number of work displacements due to a lack of demand for work and because the war destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure and economy, as in the former Yugoslavia. As a consequence, many young adult males migrated to western European countries looking for jobs and business opportunities; they then remitted resources to their families left behind in their origin countries. South-east Europe and the FSU countries were also characterized by a “care drain,” as their middle-aged women were frequently employed as carers for the elderly in western European households. This second phenomenon increased the proportion of children who grew up without their mothers. Remittances could increase household incomes, therefore improving children’s food consumption, housing conditions, health, and education services; however, there may have been some additional negative side effects, with long-term implications for children’s development and future human capital. These include changes in household composition and responsibilities, which led to more pressure being placed on older children to do housework or to enter the labor market; as a result, children in these affected households were more likely to neglect their schooling and dedicate less time to studying [3], [10].

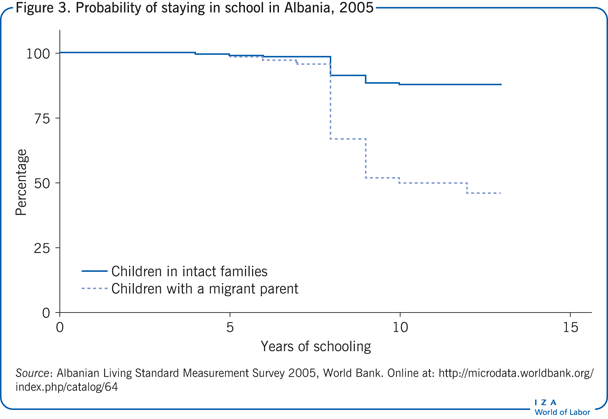

In 2005 about 860,000 Albanians, or 28% of the population, lived abroad. According to the Albania Living Standard Measurement Survey (ALSM), around 6% of children under the age of 15 were living without one of their parents because of migration and 12.9% had parents abroad at some point during the 12 months preceding the survey [10]. The ALSM is the only survey available for the region that recorded children’s residential status during parental migration, including whether they were left behind, and for how long. One study exploited these data to retrospectively reconstruct children’s schooling status during parental migration and to identify its long-term effects [3]. The main findings reveal that fathers’ emigration negatively influences children’s schooling in the long term, increasing the probability of dropping out and of delaying school progression. Figure 3 shows the probability of surviving in the Albanian school system for children with and without parental (fathers) migration. Other child or parental characteristics could explain the differences between the curves, but it still gives a descriptive indication of the educational gap that can affect children living in disrupted families. After controlling for other explanatory factors, the study finds that, in 2005, an additional month of being left behind by a parent increases a child’s probability of dropping out of school by 0.5% and the probability of attending school with delay (i.e. older than expected by the education system) by 0.6%; it also reduces the probability of in-time enrollment (at the right stage of development) by 1.1%. Adolescents suffer a higher impact: an additional month of parental migration reduces the probability of staying in secondary school by 9% and increases the probability of delay by 8%. The negative impact is even stronger for girls and for children living in rural areas [3]. These results indicate that decisions on investment in girls’ human capital may be more sensitive during parental migration because older men (e.g. grandfathers, uncles), who often take over the role of household decision makers in patriarchal families when parents migrate, may apply traditional gender norms that discriminate against women [11]. Additionally, the larger negative effect in rural areas may be interpreted as evidence that an adolescent’s responsibilities in farm households may be substantial when the father is absent, thereby reducing their ability to continue to attend school. Since parental migration occurred before the observation of children’s schooling status, the study avoids issues of endogeneity due to the two events overlapping; however, it still suffers from unobserved heterogeneity and thus results need to be interpreted carefully.

The same study on Albania finds no effects from remittances that, in principle, should have played a relevant role in relaxing families’ budget constraints and improving poor children’s educational opportunities, especially at the secondary school level [3]. In this respect, a recent study on the impact of remittances on children’s human capital development in Kyrgyzstan sheds light on their role in preventing school dropout [12]. The researchers analyze the effect of remittances on the education and health of children in Kyrgyzstan during 2005–2009; they find that secondary-school-aged boys in households that receive remittances are less likely to be enrolled in school than other children. Their interpretation, in line with [3], is that the absence of a parent can exert pressure on remaining household members to contribute more of their time to household responsibilities and working in the labor market. Children may also be supervised less when a parent is absent, and may feel the need to start working to contribute to their household’s income.

In Moldova, the share of children living without one or both parents is notably higher than in Albania: according to the Moldovan Household Budget Survey, which was carried out in 2007, about 40% of children do not live with both of their parents; among children living in non-nuclear households, this share increases to 56%. In addition, a significant share of children (slightly under 10%) live without both parents [10]. In 2006, almost 60,000 Romanian children were registered as having at least one parent working abroad; in 2008, this number increased to 92,000 (2% of the country’s children). Empirical evidence for 2007 shows that Romanian children growing up in households with one or more parent living abroad are approximately 44% more likely to get sick and be depressed [8].

Two recent studies that examine the poorest country of the region, Tajikistan, which is also one of the economies most dependent on remittances, reveal a negative association between parental emigration and school attendance of children left behind [6], [13]. Again, the highest impact is seen among adolescents and is expected to affect the school to work transition of young adults from poor families and those living in rural areas.

Parental health and children’s human capital development

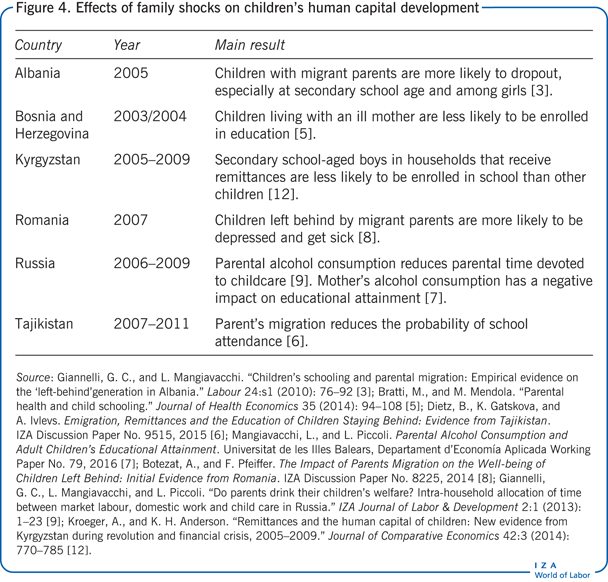

Along with underfinancing the education system, several other factors increased the cost of schooling for families in the early 1990s, causing a detrimental effect on the previously almost universal literacy rates. These factors are country specific and their study has been determined by the availability of data. Among the most influential factors are the civil wars that occurred in the former Yugoslavia, Albania, and Tajikistan in the 1990s. A study on BiH explores the nexus between civil wars and children’s educational attainment in the long term [5]. It focuses on the role parental health plays in children’s schooling (health outcomes after the war were below those of other countries in the region). Social services in Bosnia were devastated by the war; one-third of the country’s health structures (i.e. physical buildings) were completely destroyed and health financing was made inefficient with the establishment of the two independent republics, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska. Moreover, 50% of the schools in BiH required repair after the conflict. In terms of education outcomes, the secondary level was again the most affected, with 73% of all children attending school and only 57% of poor children attending. The study finds that children whose mothers had poor health statuses were between 7% and 14% less likely to attend school. Maternal illness shocks also increased the probability of children working (Figure 4).

The effect of poor parental health on children’s human capital has also been studied for Russia, which experienced severe, pervasive health problems during transition, particularly for men of prime working age (those aged aged 25−54) [7], [9]. The majority of these health problems were driven by an increase in alcohol consumption. During the transition to a market economy, increasing alcohol consumption was observed by several studies, all of them using the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (RLMS). In the early 1990s, per capita consumption of alcohol doubled among middle-aged men. In the following years, this upward trend was interrupted by an increase in the price of alcohol, until 1998 when it started to rise again (RLMS data suggest a 27% increase in alcohol consumption during the whole period from 1992 to 2000). Subsequent RLMS data (2006−2010) partially confirm the previous trends, with total daily alcohol intake showing a slight increase for men and an essentially stable path for women [9].

The amount of alcohol consumed is a relevant factor in determining fathers’ time spent administering childcare, both negatively and significantly reducing their weekly hours spent in this activity. One additional gram of pure alcohol per day for the average male drinker implies a reduction of 2.5 minutes of childcare time per week. Indeed, drinking one more glass of vodka per day, which contains about 10 grams of pure alcohol, reduces fathers’ weekly childcare time by almost half an hour. Therefore, drinking five additional glasses would imply a reduction of more than two hours with respect to an average childcare time of 9.7 hours per week. If parents’ time spent with their children is seen as a significant input for children’s educational attainment, then it follows that parental alcohol consumption during transition had a detrimental effect on human capital development [9]. Mothers’ total alcohol consumption during the transition years (1994−2001), on the other hand, hampered adult children’s educational outcomes in the 2006−2014 period—referring to years of schooling and children’s probability of having a university degree, the highest level of education achieved [7].

Limitations and gaps

The main limitation when studying the impact of transition and related microeconomic changes on children’s educational outcomes is the lack of data. First, pre-transition data are completely missing, making it difficult to control for the starting conditions. Additionally, very few household surveys are available from the transition phase, especially for Western Balkan and Central Asian countries. Even when household surveys exist, they lack information on children’s residential status and quantitative outcomes such as test scores. Another important feature often missing in household surveys is the longitudinal dimension. Very few have a panel structure, and even when a panel component exists, the number of observations is low and variables are not consistently measured in different waves.

Causal analysis at the micro level in south-east Europe and FSU countries is further inhibited by an absence of randomized experiments designed to perform unbiased program evaluations. Due to this lack of randomized experiments and of panel data, any estimation is subject to the presence of unobservable variables, which could bias results.

Finally, given the incidence of institutional childcare in many countries, an interesting field for future research would be to evaluate the impact of non-parental care on children’s long-term development. Focusing on children in formal care would be socially relevant, but for the moment, lack of data on the welfare of those children limits any possible analysis.

Summary and policy advice

There was a widespread failure by governments in south-east Europe and the FSU to provide sufficient expenditure on education during their transition to market economies; as a result, children’s educational achievements and equality of opportunities have been negatively affected. Additional factors closely related to the transition process, like parental migration or health status, are associated with higher school dropout rates.

Several studies show that different shocks at the household level further hampered children’s educational success, forced children to drop out of school, or increased their chances of being depressed and suffering health problems. Transition shocks are also negatively associated with the time parents, especially fathers, devote to their children.

Policymakers should therefore pay greater attention to expanding educational opportunities and improving the quality of the education systems in an effort to recover the stock of human capital that has been lost since the socialist period. Specific public policies should promote school attendance for children that live in precarious family circumstances; in particular, policies should focus on the children whose parents have migrated, have bad health status, or are heavy drinkers.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks three anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Economics (Grant ECO2015-63727-R) is gratefully acknowledged. Previous work of the author (together with Gianna Claudia Giannelli and Luca Piccoli) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [3], [9].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Lucia Mangiavacchi