Elevator pitch

Regulation of the minimum age of employment is the dominant tool used to combat child labor globally. If enforced, these regulations can change the types of work in which children participate, but minimum age regulations are not a useful tool to promote education. Despite their nearly universal adoption, recent research for 59 developing countries finds little evidence that these regulations influence child time allocation in a meaningful way. Going forward, coordinating compulsory schooling laws and minimum age of employment regulations may help maximize the joint influence of these regulations on child time allocation, but these regulations should not be the focus of the global fight against child labor.

Key findings

Pros

If enforced, minimum age regulation can be a useful tool to change how children work.

Regulation is strongest when coordinated with compulsory schooling laws.

Reductions in child labor can be accomplished with minimal impact on family living standards.

Coerced and forced child laborers, although a small share of working children, may benefit the most from minimum age of employment laws.

Minimum age regulation may establish new societal norms over time and may provide tools for the legal system to go after gross violators.

Cons

Minimum age regulation is not a tool to promote education.

Minimum age regulation can separate children from their parents in the labor market, leaving children more vulnerable.

Most child laborers are involved in activities that are outside the scope of minimum age regulation.

There is little evidence that minimum age regulations are being enforced.

The adoption of minimum age regulation appears to be motivated by global political concerns.

Author's main message

Minimum age regulations have the potential to reduce child labor. As currently implemented, however, they do not appear to substantively influence child employment and may lessen political pressure for more meaningful reforms. If enforced, minimum age regulations can be a useful tool to change how children work, but there is little evidence of widespread enforcement. Minimum age regulations are not a tool to promote schooling.

Motivation

There were approximately 168 million child laborers (see Child labor) in the world in 2013. Child labor is a global policy issue because of human rights and economic development concerns. Minimum age regulation is the dominant tool used to influence employer decisions to hire child labor.

Most countries have minimum age of employment regulations. These are typically based on the principles of International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention C138 on the Minimum Age of Employment and C182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Minimum age laws usually exclude family-based businesses, defined as family farms and enterprises that do not regularly hire outside workers. Employment outside family-based businesses is prohibited until a specific age (often 12). After that, it is allowed under limited circumstances, such as during daylight but outside school hours, and only in certain sectors until age 14 or 15, when employment is allowed more broadly, except in jobs that are on a country’s list of hazardous activities, which are prohibited until age 17 [1].

Despite the ubiquity of these laws, their economic impact and influence on child labor are not well understood. This paper considers the effect of minimum age laws on child labor and schooling in contemporary, low-income economies, using empirical evidence when available. There are some important potential consequences of minimum age regulation that have been examined only theoretically, however. Much of the discussion is based on data from the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, referred to as MICS data. These data are representative of 156 million children aged 8–14 living in 59 mostly low-income countries.

Discussion of pros and cons

Enforced minimum age regulations would change how children work

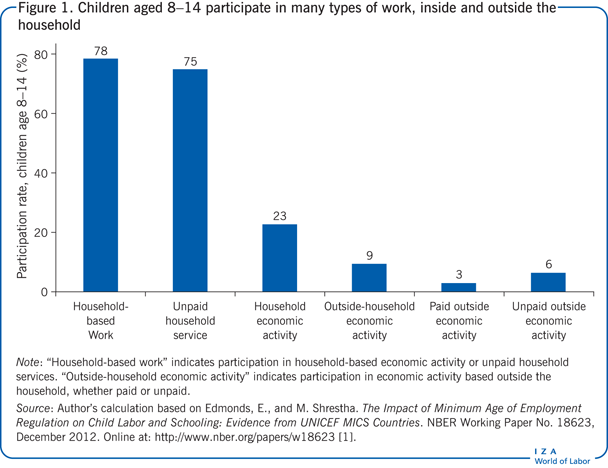

Children can make productive contributions to their households in many ways by working inside and outside the household (see Figure 1). Participation in unpaid household services is widespread and important. Children cook, clean, shop, and take care of dependents in their family. Participation in these unpaid household services is 25 times more prevalent than paid employment in the MICS data. Some 23% of children aged 8–14 also contribute economically to their households through participation in family farms and enterprises.

Economic activity outside the household is far less prevalent, with unpaid economic activity outside the child’s home (for example, helping on a neighbor’s farm) the most common form of outside activity. The MICS data show that just 3% of children aged 8–14 work for pay. There is cross-country variation, but the rarity of work outside the home for children is not unique to the MICS data.

Minimum age regulations usually exclude family-based businesses. Both pragmatic and moral arguments are used to justify the legal focus on work away from home. Employment inside the home is often unobserved by the regulator, and the regulatory infrastructure required to identify and monitor in-home production is prohibitively costly. On the ethical side, people tend to view work done in a family context as fundamentally different from work done for someone outside the family. A case can be made for questioning the basis for this view. Children could be more exposed to hazards and risks inside the household than outside, despite the proximity of their parents, given the general, unregulated status of household-based economic activity. Regardless, the view that regulation should not interfere with child engagement in family-based businesses is widespread in minimum age laws.

However, minimum age laws often reach inside the family for activities classified as a worst form of child labor. Signatories to ILO Convention C182 agree to create a list of activities that are prohibited for children in the country, regardless of the location of the work. But without any infrastructure to regulate family-based activities, the list of prohibited activities probably has less influence inside the household than out.

Most children are thus involved in activities that are outside the scope of minimum age regulations, as currently implemented. Household-based economic activity is seven times more prevalent than paid employment outside the child’s home, and household-based work is 26 times more prevalent (see Figure 2).

Because most child employment is outside the scope of minimum age regulations, enforcing such regulations would largely divert children out of regulated activities into unregulated activities, doing little to change the prevalence of child economic activity or promote schooling. For example, the MICS data show that four out of five children working in paid employment also work inside their home. Most provide unpaid household services, and 40% participate in household economic activity. If their participation in work that is not family-based were restricted, they would likely substitute that time for that of other family members engaged in family-based work [2]. The idea that enforced minimum age regulation would largely change the type of work in which children engage (without reducing their time allocation to labor) is not necessarily problematic for policy when certain types of jobs (say, work outside family-based businesses) are deemed less socially desirable. Moreover, if regulated and unregulated labor can be easily substituted for one another, the economic effect on families of the loss of a child’s regulated job should be minimal.

The idea that enforced minimum age regulation primarily diverts children from regulated activities to non-regulated activities rather than that it eliminates child employment is different from the premise in most theoretical papers on minimum age regulations, which usually assumes that there is only one potential job available to the child (which minimum age regulation prohibits). In the most cited model in the child labor literature, there is only one sector of employment for child labor, and regulation can completely prohibit it [3]. A later refinement adds a second, unregulated sector [4]. In this two-sector model, the reduction in employment in the regulated sector can depress wages and increase overall child labor in the economy (if the unregulated sector is also child labor) as lower household incomes induce more children to work.

In the context of minimum age regulation, it would be surprising for an activity to be legally defined as child labor in a country but be permitted under minimum age regulation. As such, the result in the two-sector model is better understood as showing that children can work more when their labor is prohibited in one sector When there are disamenities associated with a worst form of child labor, the worst form of child labor may pay more [5]. Because there are only two sectors, families affected by an enforced ban on the worst form of child labor are made worse off financially, as they lose the high-paying job. If a continuum of employment opportunities is available in unregulated sectors, then regulation should change how children work without influencing whether, or how much, they work.

The literature on coerced or exploitative labor also considers the impact of labor regulation in a substantively different way. For example, credit constraints and insurance failures can induce families to send their children into bonded-labor arrangements, where children are paid less than the value of their economic contribution [5]. Or, in a more general setting, employers can exploit children by paying below the value of their economic contribution [6]. These papers differ from the literature just discussed by focusing on types of labor where agents are not free to allocate their time in ways that maximize their well-being. When coercion is present, efforts to prohibit these anti-competitive institutions can make the worker and society unambiguously better off. While coerced and forced child laborers are small shares of working children, these child laborers may benefit the most from minimum age of employment laws. Unfortunately, the empirical literature has nothing to say about the impact of minimum age regulation on child employment in these worst forms of child labor.

Even in competitive labor markets, diverting children from regulated to unregulated sectors may have undesirable consequences beyond the economic ones for child laborers and their families. First, most working children work alongside their parents. The parents’ presence can protect the child from others’ and from the child’s own impaired decision-making. If regulation separates parents and their children (parents in the regulated sector, children in the unregulated sector), children may become more vulnerable to adverse consequences of employment by working in child-only activities [7]. And if the regulated sector is more visible, and children in that sector are more apt to compete with adults, removing children from that sector might diminish political support for a broader effort against child employment [8].

This discussion has assumed that minimum age regulations are enforced. The next section presents evidence that minimum age regulations are not enforced in general.

Minimum age regulations are rarely enforced

Minimum age of employment regulations have existed in high-income countries since the late 19th century. In the US, the first child labor laws were targeted at manufacturing employment, but legislation to enforce the laws with inspectors lagged behind passage of the law [9]. Several studies have found a correlation between the adoption of child labor laws in US states and employment in manufacturing, but the laws tended to follow declines in child labor rather than lead them. When this is taken into account, minimum age limits in manufacturing at the turn of the 20th century seem to have had little influence on child involvement in manufacturing and played a negligible role in the long-term decline in child labor in the US [9].

There are three key differences between modern minimum age regulations and those adopted around the turn of the 20th century in the US and elsewhere. First, modern regulations cover a broader range of economic sectors. Second, modern regulations are generally adopted in settings where child labor is more prevalent rather than where it has been nearly eliminated. Third, external, international pressures are a larger force in the adoption of modern child labor regulations, leading to considerable consistency in regulations across countries and perhaps explaining why so few resources are devoted to enforcing the regulations.

One study examines the impact of laws that restrict the minimum age of employment, using MICS data for 59 countries with minimum age of employment laws in place [2]. Because enforced minimum age laws change the distribution of employment by age, it is worth looking at how much of the variation in paid employment can be accounted for by age differences between children. Very little, it turns out. Household characteristics, such as community of residence, parental education, and income, account for 63% of the variation in paid employment in the 59 countries. In none of the countries does age account for more than 3% of the variation in paid employment (the average is below 1%). Even if all the variation in paid employment associated with age is attributed to minimum age laws, which would be unrealistic, since older children are also more mature, productive workers, the laws seem to be of minimal importance in accounting for the variation associated with age.

Minimum age regulations could influence how children work even if age is a small portion of the variation in child engagement in paid employment. Examining whether paid employment is higher at the minimum age than researchers would expect can test for evidence of enforcement of minimum age laws. The key challenge is forming the expectation of what the prevalence of paid employment would be if minimum age laws were not relaxed at their current age. This is done by estimating the age trend in paid employment at ages below the minimum age and projecting that age trend to the minimum age [2]. In effect, this yields estimates of the effect on paid employment of extending current minimum age regulations by one additional year, assuming no other changes in the economy.

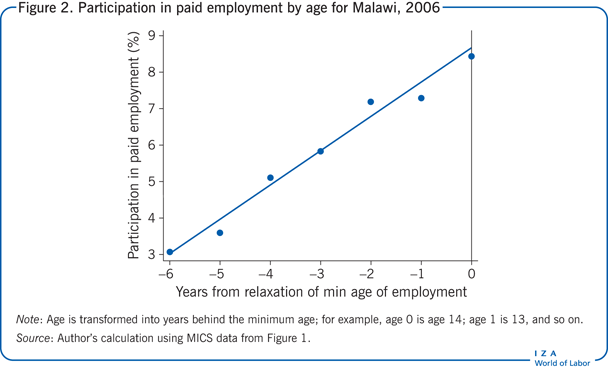

Consider the example of Malawi. After signing ILO Conventions C138 and C192 in 1999, Malawi passed the Employment Act of 2000, establishing 14 as the minimum age of employment. Home-based work is explicitly exempted from the law, and schooling was not compulsory at the time covered by the data (2006). Plotting participation in paid employment (illegal before 14) by age yields several interesting observations (see Figure 2). First, there is child participation in paid employment below the minimum age, even though it is illegal. It is obvious that the law is not perfectly enforced, and empirical research on minimum age of employment does not have perfect enforcement as a hypothesis to test. Instead, researchers test whether there is any evidence of enforcement. Second, participation in paid employment increases with age. A 12-year-old is more than twice as likely to be in paid employment as a 9-year-old. Third, actual paid employment at the minimum age of employment is lower than would be expected based on the estimated age trend of paid employment in Malawi.

Using the same approach to examine the impact of the minimum age of employment regulations in the 59 countries in the sample shows no changes in child time allocation that would be consistent with an impact of minimum age restrictions in any of the countries [2]. However, in two countries, Burundi and Kyrgyzstan, where compulsory schooling laws match up with minimum age of employment laws, the pattern of results appears consistent with an effect from compulsory schooling laws.

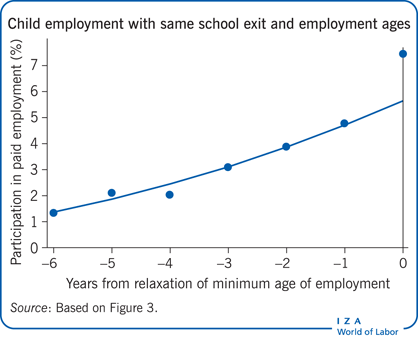

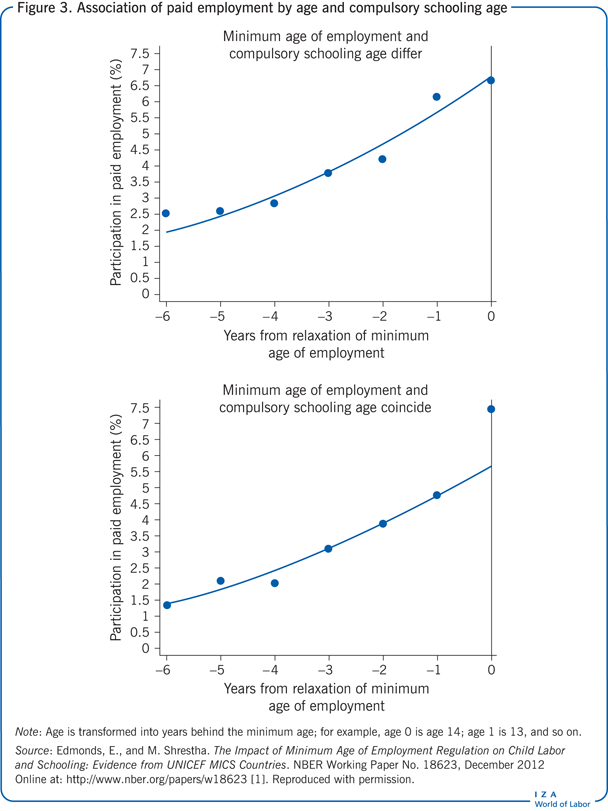

The same pattern emerges when data are pooled for all 59 countries [1]. The data are plotted for paid employment relative to the minimum age of employment for countries where compulsory schooling ends at the same age as the minimum employment age and for countries where the two ages differ (see Figure 3). In countries where the two ages differ, paid employment at the minimum age is lower than would be expected. Thus, there is no evidence consistent with an effect of minimum age regulation on paid employment. But where the two ages coincide, paid employment is much higher at the minimum age than would be expected, thus supporting an effect for a combination of minimum age regulation and compulsory schooling laws.

In considering the pattern of changes in time allocation, the researchers argue that the data are consistent with the hypothesis that it is the end of compulsory schooling that influences time allocation rather than the relaxation of minimum age restrictions [1]. This finding from contemporary developing countries is similar to the findings of a study on the impact of compulsory schooling laws in US states in 1900 [10]. The study is able to reject the null hypothesis of no effect of compulsory schooling laws on education, except when the compulsory schooling laws match the minimum age of employment laws.

If there is little evidence of widespread enforcement of minimum age of employment regulations, why has so much energy gone into adopting them? These regulations may provide benefits that have nothing to do with changing the time allocation of children at the minimum age and therefore that go beyond their direct influence on the prevalence of child labor. They may establish new societal norms over time. They may provide tools for the legal system to go after gross violators, such as incidents of forced labor. Or they may provide organizing principles for other government anti-child-labor laws. However, it is clear that there is not much current evidence or historical precedent showing that these regulations, in isolation, substantively shape the employment patterns of children.

Limitations and gaps

There are several important limitations on current evidence. First, the failure to find evidence of effects of minimum age regulations on paid employment does not rule out the possibility that future regulations could have substantial ones. Second, the evidence does not exclude the possibility that current laws were used to shift children out of a particular, more detrimental sector or class of jobs into other paid jobs. This diversion might be desirable from a policy perspective if one type of paid employment is substantively worse than another. Third, if regulations were used only to move children out of rare types of work, the research design would not have the statistical power to detect these effects even if the children were not diverted into other types of paid employment.

It is also important to consider what the estimates of the effect of minimum age laws in the studies are measuring [1], [2]. The empirical approach answers only the question of what would happen to paid employment if minimum age of employment regulations were extended an additional year. If minimum age laws shift the entire age distribution of employment, or have gradual, cumulative effects on employment, this approach could not detect these effects. The limited question considered in these studies could be resolved by focusing on countries that change their laws.

Beyond this, observational studies of this type are poorly equipped to identify the effects of laws and regulations that affect the country as a whole, changing the child labor picture compared with a country without such laws. For example, if minimum age regulation eliminated many children from the labor force, it could raise wages for adults. Higher wages for adults would weaken poverty motives for child labor but would not be detectable in a study design like that characterized in Figure 3. These sorts of broad, general effects of existing minimum age regulations seem unlikely, given that there does not appear to be variation in paid employment around the minimum ages, but such effects cannot be ruled out using the data and study design employed in existing evidence.

Summary and policy advice

There is very little evidence that current minimum age of employment regulations are influencing child engagement in paid employment. Nearly every country in the world has minimum age of employment regulations. Yet a review of 59 mostly poor countries did not find conclusive evidence of an effect of minimum age regulations in a single country.

Research from US history with minimum age legislation suggests that the impact is largest when the legislation is coordinated with the compulsory schooling age laws. The evidence from contemporary developing economies is consistent with this hypothesis (although it does not test it directly): Coordinating schooling and employment regulations may help maximize the joint influence of these regulations on time allocation.

Beyond the suggestion of coordinating schooling and employment regulation, are there any other clear policy principles that follow from the evidence discussed here? The evidence illustrates that merely adopting regulations on child employment is not sufficient to influence child labor. The global fight against child labor might be better served by focusing less on the laws that exist and more on their implementation and enforcement, as well as by addressing the root causes of child labor.

The broader evidence on the determinants of child labor does not provide much basis for the idea that child labor is driven by the prevalence of widespread, lucrative employment opportunities that regulation can take away. A number of studies document large declines in child employment when poverty is moderated. Disasters and droughts, even those that dry up employment opportunities, seem to be associated with more child labor. Overall, while employment regulation might be a component of an overall child labor policy, there is not a strong theoretical or empirical basis for putting minimum age regulation at the center of global efforts to improve the lives of poor children.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. He is also grateful to Mahesh Shrestha for insightful discussions on the papers that fed into this article. The author acknowledges significant financial support from the US Department of Labor, ICF International, the ILO, UNICEF, and the World Bank for consulting services related to child labor. He serves as an advisor to the Goodweave Foundation and the Understanding Children’s Work Project.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Eric V. Edmonds