Elevator pitch

Developing countries often face two well-known structural problems: high youth unemployment and high inequality. In recent decades, policymakers have increased the share of government spending on education in developing countries to address both of these issues. The empirical literature offers mixed results on which type of education is most suitable to improve gainful employment and reduce inequality: is it primary, secondary, or tertiary education? Investigating recent literature on the returns to education in selected developing countries in Africa can help to answer this question.

Key findings

Pros

Private returns to secondary or tertiary education in Africa are higher than returns to primary education, regardless of the level of development.

Lack of skilled manpower is identified as an important factor that impedes the competitiveness of firms and the modernization of the economy; investment in vocational and higher education is critical to address this skill gap.

An increase in the proportion of people with higher education may reduce wealth or income inequality.

Cons

Unemployment in developing countries tends to be higher among those with secondary or tertiary education; expanding higher education may therefore fuel unemployment.

Governments invest in primary education to address inequality in a populist manner; this also reduces the political appetite for increased investment in higher education.

As access to higher education is largely limited to high earners, expansion of higher education could potentially exacerbate inequality.

Author's main message

Projections indicate that the global labor market will face continued disequilibrium. Excess labor supply is expected from less developed regions, while excess demand is expected from developed and emerging economies. At the same time, the global economy is becoming increasingly knowledge-driven. Hence, investment in vocational and higher education is important for developing countries to remain competitive; further, expanding the skill-base of the labor force may lead to lower levels of wealth inequality. In the case of Africa, despite some contrary arguments, policymakers should promote economic modernization by prioritizing investment in higher education.

Motivation

Demographic projections indicate that most of the world will experience an aging and declining labor force over the coming decades. One significant exception is the continent of Africa, which is projected to have the youngest and largest labor force during this period. This expected shift in the geographic distribution of the labor force has serious implications for the global economy as well as for regional economic partnerships. However, in the African case, the labor force will only be able to provide substantial value, both within the continent and globally, if it is employable and competitive across a wide range of sectors. If the past is any indication, there is much catching up to do on the part of policymakers to increase the skill composition and stock of the African labor force. Data on educational enrollment rates in Africa over the past decades show a rising trend for primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. However, the unemployment challenge, particularly among youth and the well-educated, remains persistent [1]. Projections indicate that, over the next 30 years, close to 29 million young people will join the labor force in search of employment [2].

Meanwhile, evidence from Enterprise Surveys indicates that firms generally consider lack of skills as one of the major operational constraints they face in Africa [3]. The mismatch between demand and supply is a serious structural bottleneck, which can be blamed in part on the educational system that has been entrenched in many of these countries since their independence.

Discussion of pros and cons

In order to address persistent unemployment among the educated, and to maintain competitiveness, reforming the education system becomes the most important policy challenge in developing countries. Significant questions revolve around whether the emphasis should be on primary (i.e. grades 1−6) or higher-level education (i.e. including advanced post-graduate institutions and research centers). The debate is further complicated by the mixed evidence on private/individual returns to education in African labor markets, as well as, by implication, to equality when it comes to the utilization of publicly funded and subsidized schools.

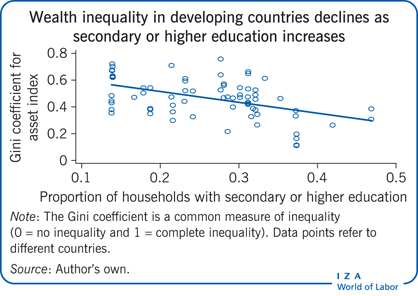

Apart from chronic youth unemployment, most African countries also exhibit high and persistent levels of wealth inequality. The role of education in overcoming intergenerational mobility, and thereby inequality, has been documented in many studies, though it is not clear which level of education is most important for the effective reduction of inequality. As shown in the Illustration, the Gini coefficient, a common measure for inequality, decreases with the share of the population that achieves secondary or tertiary schooling.

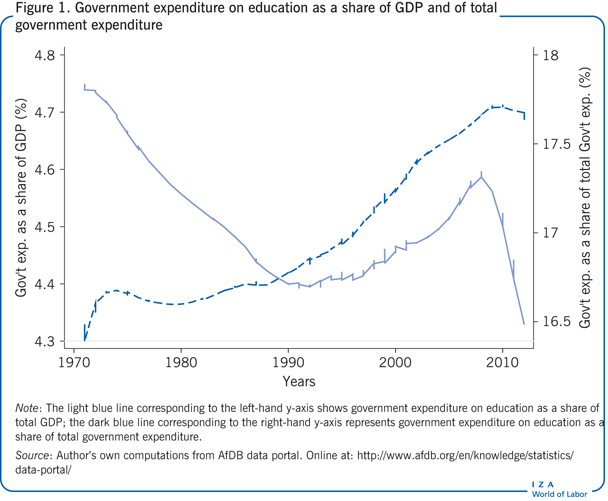

Widely accepted studies claim that returns to primary education in Africa are higher than secondary and tertiary education [4]. This result has had profound effects on public spending on education, particularly among international donors, where investment in primary education has increased substantially in the past decades due to the overarching objective of reducing poverty and inequality. Coupled with the advent of the Millennium Development Goals, which posited universal primary education as one of its goals to be achieved in 2015, significant effort and energy has gone into accelerating and expanding primary education at an unprecedented pace. The overall effect has been an increase in the share of spending on education as a proportion of total government expenditure, though the cumulative importance of government expenditure as a component of GDP has declined over the years (Figure 1).

While public policy is riding high in favor of primary education with unprecedented investment being made to expand its outreach, a series of studies indicate that returns to higher education are in fact much larger than returns to primary education [5], [6], [7]. However, some note that this fact alone should not be sufficient to reverse the established trend of investing in primary education in favor of higher education. One line of reasoning claims that it makes even more sense to continue to emphasize primary education, because individuals will be more likely to invest in their own education if they understand that the return to higher education is greater. In other words, if the payoff from higher education is sufficiently large, then individuals will invest more of their own wealth to enroll in (and thereby support) tertiary education, meaning governments can prioritize support for primary education, as private investment will provide the necessary financing for higher education. This argument is further strengthened by a number of studies that suggest the subsidizing of higher education is less equitable than primary education. This result is based on evidence showing that students at the secondary or tertiary level most often come from affluent families, who can afford to pay for that education anyway. Considering this position, policymakers would be better off supporting primary education, thus leaving the financing of higher education to the discretion of (generally affluent) individuals.

There is an additional rationale for why politicians in developing countries place such an emphasis on promoting primary education: the vast majority of their constituents are not well educated. This provides a populist-driven incentive to demonstrate governments’ support for social welfare programs by devoting funds to programs that immediately benefit the largest number of people. In most African countries, when it comes to education, the choice made by governments has clearly been to prioritize primary above higher education.

Shifting focus from primary to higher education

Despite the previous discussion, some emerging trends in the policy discourse favor a shift in emphasis from primary to higher education. The first is the dire need for Africa’s economies to diversify and to undertake structural change to sustain the current economic growth spurt. In this regard, enhancing the composition and skill level of the labor force becomes important. Recent research suggests that most of the recent growth seen in many African countries is mainly a result of booming commodity prices and a favorable international investment climate, particularly in the extractive industry sectors [8], [9]. However, the intensity of employment generated during this period of rapid growth has been very low [10]. This is primarily because there has been very little improvement in the production and employment structure of African economies. Stylized facts from around the world suggest that a process of structural change is necessary to sustain growth, and further, to spread its benefits to a wider population. As part of its investigation into the challenges faced by African firms that attempt to upgrade their technology and more effectively enter the value chain structure, the African Economic Outlook reports that close to 60% of respondents suggested a lack of skilled labor as one of the most important and critical constraints they currently face [3].

The second factor is widespread chronic unemployment, particularly among the young and the well-educated. Youth unemployment is not a unique phenomenon, but unemployment for the well-educated is somewhat uncommon. This can be traced in large part to the low technical level of most industries in developing nations. Firms have not built up a significant enough demand for highly skilled jobs, which leads to lower employment levels for the well-educated. Additionally, the training that youth receive may not match the skillsets demanded by employers. This issue can be addressed by a process of structural transformation, whereby demand for labor in the highly skilled sectors catches up with the available supply of skilled workers. As the pressure to expand free primary education continues, most African governments have not invested much to reform higher education to meet the needs of the emerging modern sector. Since independence, vocational and higher education in Africa have been designed to serve the needs of an expanding public sector; comparatively little change has occurred over the years in terms of the quality or quantity of higher education, which could have helped address the demands of the private sector.

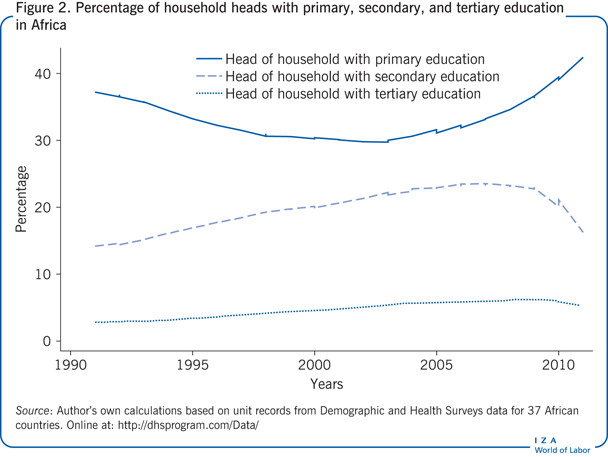

In some cases, the private sector has stepped in to fill this educational void, so that the number of privately run colleges and higher learning institutions has mushroomed in many developing countries. Even so, most graduates from these institutions have not been able to find jobs, worsening the already bloated ranks of the unemployed. It is important for governments to take leadership roles in order to reform and tailor higher education to better serve the skill requirements of the economy. However, even though unemployment among those with education at secondary or tertiary levels seems high in most parts of Africa, it is important to note that there are very few people within the labor force with such a level of education, and that this number has not seen significant growth over the years (Figure 2).

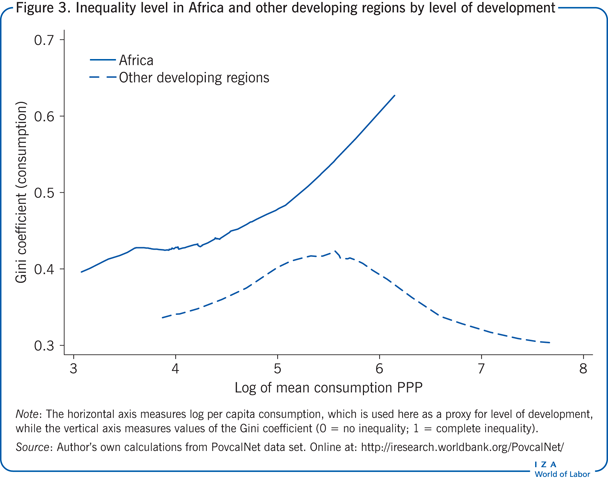

The third factor involves the potential role that higher learning can play in reducing inequality. There is consensus among researchers that Africa is the second most unequal region in the world (behind Latin America), and has remained so for many years without much improvement [11]. As an example, the Gini coefficient (a measure of inequality) remains high, even increasing with higher per capita consumption in African countries; conversely, it declines for non-African countries with high per capita consumption levels. While puzzling, the fact remains that compared with other developing regions, Africa’s inequality level is consistently high, regardless of the level of development (Figure 3).

Efforts at understanding the underlying causes of inequality in Africa have not offered much policy insight; ethnic fractionalization is the only relevant variable that has shown a consistently robust correlation with inequality. Part of the reason for this could be data problems regarding the measurement of income or consumption inequality (as measured by, for example, the Gini coefficient). Very few countries offer multiple data observations over time, which would allow for robust statistical analysis to capture policy-relevant factors that determine economic opportunities. An alternative data source that uses a wealth index from the Demographic and Health Survey indicates a strong and robust relationship between higher education and asset or wealth inequality [12]. Countries with a higher proportion of households with secondary or tertiary education levels also exhibit low levels on the Gini index for assets or wealth. For instance, a one-standard-deviation increase in the proportion of households with higher education could lead to a 17% decline in the Gini coefficient, which is substantial. In other words, the level of wealth inequality in African countries declines significantly as the share of highly educated households increases. Thus, focusing on secondary and tertiary education could potentially reduce inequality in Africa in the long term.

Results from one of the broadest studies dealing with returns to education in Africa (i.e. more countries are examined than in most other comparative studies) indicate a significantly higher rate of return to secondary and higher education in comparison to primary education [7]. However, it should be noted that the “rate of return” from higher education declines as the proportion of the population with higher education increases [13]. If this trend also applies to the respective wages of educated persons, then a rapid expansion of higher education may lead to a declining rate of return (i.e. a decline in earned wages) over time. This is actually an intuitive conclusion. The very reason that higher education commands a higher rate of return is because of a scarcity of people with such qualifications.

It may also be that the strong negative relationships between asset inequality and the proportion of people with higher education seen in the Illustration could be due to a gap in asset ownership between those with higher versus primary education, which is larger in countries with relatively low incomes.

Limitations and gaps

Examining entire continents from an empirical approach presents significant challenges, not least of which is the broad diversity found among the various countries and cultures that make up the continent as a whole. Africa fits this bill precisely; it is a macrocosm of many countries with distinct historical, cultural, and political precedents. The significant heterogeneity among these countries makes it virtually impossible to generalize continent-wide results from studies undertaken in only a few countries. This is the case in the vast majority of the existing literature that deals with returns to education in Africa. One key exception, which examines more than just a handful of nations, investigates 12 African countries and shows greater returns to higher than to primary education [7]. However, it is not clear if the results remain valid for the labor markets in the remaining 42 African countries not covered in this study.

In addition, key limitations abound when evaluating private returns to education, including unobserved factors such as ability, social networks, political affiliations, and other non-cognitive skills that tend to influence earnings independently of education, but that are often captured in studies as effects of schooling. Furthermore, most studies rely on cross-sectional data to estimate returns to education, which overstates the true contribution of education in most cases. Availability of repeated data on the same individuals could significantly reduce such upward biases.

Only a few studies exist that help guide effective policy choices with regard to the benefits of education to society at large [5]. Higher education, including advanced post-graduate institutions and research centers, provide valuable social externalities that cannot be easily quantified. Even if private returns to education decline as a country expands these opportunities to more and more people, it may still be “profitable” from society’s point of view to invest in higher education. The size of the middle class also tends to rise along with better education; a growing middle class helps provide society with the benefits of social and political dynamism that contribute to an overall prosperous future.

Summary and policy advice

As is the case with developing countries the world over, most African countries have reached a critical point, where demographic pressures necessitate a rapid transformation in their economies. These countries must transition from a subsistence-based, largely informal economy into a modern and dynamic one, where skill formation takes precedent in public policy. Repeated surveys suggest that a lack of skill remains one of the most important constraints that firms face in order to remain competitive and dynamic. Current trends show that most African countries have weak post-secondary and higher education institutions. The unemployment rate among the educated, and particularly the well-educated youth, is very high in most urban areas. This situation undermines the argument in favor of increasing the supply of higher education, as it could be contended that the supply of educated workers already outpaces demand. However, the intention of reform is not simply to increase the supply of people with higher education, but to carefully tailor their training to meet the specific demands of the private sector.

The prevailing view, which suggests that an emphasis on higher education may in fact exacerbate an already significant issue with inequality, is contested in this paper. Considering the fact that in most developing countries the majority of people who complete secondary or tertiary education come from families already in the top 20% wealth bracket, it may be that more secondary or tertiary education could lead to even greater inequality, particularly in the short term. The timespan under consideration may matter significantly, such that a short- to medium-term rapid expansion of higher education may initially lead to higher inequality. However, in the very long term, intuition and evidence seem to suggest that higher education can help reduce inequality, if labor markets remain stable and economic growth continues uninterrupted.

Alternatively, the opposite argument may hold true. If governments do not expand opportunities to people from poor families to rise out of poverty through educational means, then existing inequality could widen even further.

It is necessary to nuance the policy message at this point by noting that higher education includes a wide variety of topics and degree programs, each of which may have different effects on labor markets and the economy. In the past, higher education in Africa was primarily designed to serve the public sector, particularly by training a workforce skilled in management, law, and economics. This has grown into an increasingly outdated model, as the private sector becomes a more important player in the generation of jobs, mainly in the limited high-skilled sectors such as accountancy, engineering, management, and law.

Thus, it is possible that the rapid expansion of higher learning may be beneficial not only as a response to the growing demand for skilled labor in modernizing sectors, but it may also lead to lower levels of inequality in the process. The theoretical mechanism works as follows: the greater the proportion of people with higher education, the more likely it is that the wealth/asset gap between those with higher education and those with primary education declines over time. However, in the labor market, this may not necessarily be the case as demand may keep pace with supply, so that the return to higher education may remain constant, or even increase, potentially leading to greater inequality.

With all this in mind, there are several important unresolved conceptual and methodological problems involved in measuring returns to education; these issues create considerable uncertainty when attempting to extrapolate policy advice from the existing studies (see for example [13] for a detailed discussion). While there are many who would argue that the current trend of prioritizing primary education is the correct course of action for much of the developing world, there is also sufficient cause to refute that position.

In sum, if one accounts for the broader “social returns” that result from investment in higher education—including advances in science, research, and other key fields—then there may indeed be good reasons for policymakers to place greater emphasis on higher learning in Africa.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author (e.g. [12]) has been used intensively in all major parts of this article.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Abebe Shimeles