Elevator pitch

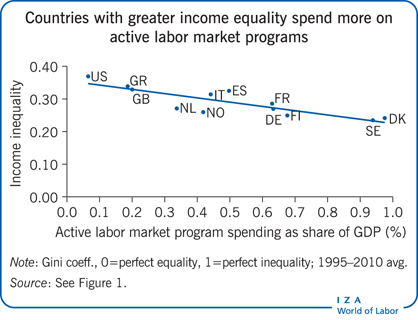

Active labor market programs continue to receive high priority in wealthy countries despite the fact that the benefits appear small relative to the costs. This apparent discrepancy suggests that the programs may have a broader purpose than simply increasing employment—for instance, preventing anti-social behavior such as crime. Indeed, recent evidence shows that participation in active labor market programs reduces crime among unemployed young men. The existence of such effects could explain why it is the income-redistributing countries with greater income equality that spend the most on active labor market programs.

Key findings

Pros

Participating in an active labor market program reduces the propensity of unemployed young men to commit crime.

Program participation leaves less time for other activities, including criminal activities.

The effects might be long-lasting, since the programs seem to change the lifestyles of participants.

Long-lasting scars from unemployment—expressed through criminal activity—might be lessened by a well-designed active labor market policy.

While unemployment shocks cannot be avoided, active labor market programs might constitute a reasonable second best to employment for less fortunate young people.

Cons

Active labor market programs are expensive, and the intended benefits of reducing unemployment are lower than the costs.

Direct measures to reduce crime are likely to be more effective than tackling crime indirectly through active labor market programs.

While good active labor market programs enhance crime prevention, they tend to reduce the threat effect (people leaving unemployment in order to avoid participation in the programs).

Good programs can have a lock-in effect that delays reemployment.

Participating in active labor market programs, by leaving less time for job search, could reduce the effect of unemployment on wages and result in higher equilibrium unemployment.

Author's main message

Unemployed young men commit less crime when they are enrolled in active labor market programs than when they are not. This relationship suggests that unemployment leads to more crime not only because of the drop in income, but also because inactivity in itself is bad. This outcome may reflect more than an incapacitation effect since young men enrolled in active labor market programs commit less crime not only on weekdays but also during weekends, when programs are closed. Being engaged in purposeful activities seems to have a positive effect on the lifestyles of unemployed youth.

Motivation

Active labor market programs are widely used in most economically advanced countries. The programs incorporate a range of voluntary and mandatory activities for unemployed individuals, such as job-search assistance courses, training, education, and relief work. OECD countries spent an average of 0.34% of GDP on such programs in 2012, close to a third of all spending on labor market programs. Spending across countries varied from less than 0.1% to almost 1%, with the highest spending among high-redistribution, low-inequality countries (see Illustration).

The high-spending countries might see active labor market programs as part of a larger social effort, because they expect active measures to reduce anti-social behavior such as criminal activity in ways that passive programs do not. It is well documented that having a job reduces the propensity of young people to commit crimes [1], [2], [3]. It may be that active labor market programs, even if they do not reduce unemployment in the short term, have a similar effect on crime as employment, as a result of engaging unemployed individuals in purposeful daily activities.

Furthermore, active measures may reduce the social marginalization experienced by some people. This means that active labor market programs might have both a direct crime-reducing effect and an indirect effect by enhancing the effect of other initiatives such as subsidized education. Both the direct and the indirect effects would increase the chances that vulnerable young people enroll in education or find jobs.

Discussion of pros and cons

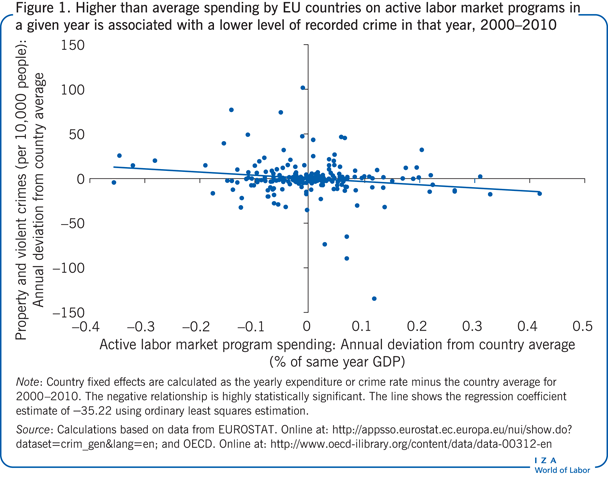

An analysis of EU countries using cross-sectional data suggests that active labor market programs might reduce crime. Figure 1 reveals a clear, statistically significant negative association between spending on active labor market programs and the crime rate (for property crime and violent crime reported to the police). The figure can be interpreted to show that, independently of whether a country has a high or a low crime rate or whether it spends less or more on active labor market programs, higher than normal spending on active labor market programs in a given year is associated with a lower level of recorded crime in that year. Differences in active labor market program spending among countries explain around 10% of the differences in the crime levels of high-crime and low-crime countries.

The negative relationship shown in Figure 1 cannot be interpreted as a causal relationship, however. Although crime goes down in countries that increase their spending on active labor market programs, this could be because crime, in some way, triggers the higher spending. If, for instance, higher crime rates boost youth unemployment because of the stigma associated with crime, this could generate such reverse causality. Alternatively, the negative relationship could reflect changes in some third unknown factor that influences both crime and spending on labor market programs. For instance, if a country that increases spending on active labor market programs reduces its spending on unemployment benefits, this might reduce unemployment. The reduction in unemployment and not the increased spending on active labor market programs might then have led to the lower crime rate.

However, recent evidence suggests that the link shown in Figure 1 could be causal—that for a given country, higher spending on active labor market programs actually reduces crime [4], [5]. This possibility is examined below.

Framework and analysis

The hypothesis that spending more on active labor market programs reduces the level of crime draws from both economic and sociological theory. Economic theory predicts that an individual will commit a crime if the expected return is higher than that of the best alternative activity, for instance, formal employment. Because people have different preferences, they may evaluate the alternatives differently, which allows for the possibility that people will behave differently in otherwise similar situations. The primary strength of economic theory in this case is that it gives clear predictions regarding how the propensity to commit crime changes as the relative return from the two alternative activities—crime and no crime—changes. Some of the factors behind the returns from the two alternatives are standard economic variables (such as the wage for formal work, the value of leisure, the marginal utility of wealth, the risk assessment of being caught and punished, the penalty arising from being caught). Others are social factors (such as the stigma of being convicted of a crime, the disutility of guilt, a sense of belonging, and loss of self-esteem from transgressing group norms).

The hypothesis that participation in an active labor market program will reduce the propensity of an unemployed individual to commit crime draws on all these factors for possible channels for the transmittal of that effect. Active labor market programs might improve the work and social skills of people who are unemployed and strengthen their job and social networks. By raising the value of a life without crime, all these factors will increase the expected cost of committing crime. Finally, participating in purposeful activities might change a person’s self-image and increase the aspiration to be self-reliant, again boosting the value of a life without crime [6]. An underlying assumption is that committing a crime makes it harder to get a good job and to become linked with strong social networks.

Thus, participating in an active labor market program might influence the chance that an individual will engage in crime in various ways, whether by affecting how much crime is committed by a given individual or by motivating an individual to refrain from criminal activity altogether. More specifically, active labor market programs may work through four channels [4]. First, programs may reduce crime among unemployed individuals indirectly by increasing their level of employment; having a job may deter criminal activity by raising people’s income or by occupying more of their time. Since the employment effect of active labor market programs is small, on average, the effect on crime through this channel is also expected to be small. Second, active labor market programs might affect crime indirectly through a higher income effect if program participants receive higher unemployment benefits than other unemployed people do. Third, programs might have a direct effect because program activities may leave less time for crime—an incapacitation effect [7], [8]. Finally, a direct effect might be that active labor market programs change the lifestyle of a participant from one that is receptive to criminal activity to one that is not—for instance, to one that is driven by the expectation of a better future, either because program participation has led to an understanding of how a criminal record could jeopardize one’s chance for a normal productive life or simply because participation has changed the person’s values and perspectives, his or her “habitus,” to use Bourdieu’s term [9].

In terms of “treatments,” the similarities for unemployed individuals between becoming employed and participating in an active labor market program relate to the two last direct effects: in both circumstances (employed and unemployed but participating in an active labor market program), people have less leisure time and they spend more time on activities that are associated with better future prospects than when they are simply unemployed (although the future prospects are probably viewed as being better from the perspective of holding a real job than from that of entering an active labor market program). The main short-term difference is that getting a job results in a real increase in income, which is typically not the case when entering an active labor market program. Specifically, the evidence discussed below considers programs where unemployed individuals receive the same level of benefit regardless of whether they participate in active labor market programs or are able to control for changes in income when an unemployed individual goes from passive unemployment to active. Thus, the evidence concerns the pure effect of being active (employed or enrolled in an active labor market program) compared with being passive (unemployed and not enrolled in a program).

This is an important issue in itself, with direct policy implications, but it can also shed light on the link between becoming unemployed and having an increased propensity to commit crime. Does the explanation lie in the drop in income, the loss of a purposeful daily routine, or both? The drop in income seems to be at least a contributory factor: not only does unemployment lead to an increase in crime, but a further decrease in unemployment benefits while a person is unemployed seems to increase the amount of crime committed [10].

Nevertheless, that participants in active labor market programs commit less crime than others who are unemployed suggests that it is more than the change in income that makes employed people commit less crime. The mere fact that people are engaged in some activity seems to matter as well. This effect could arise simply because of an incapacitation effect: program participation allows less free time in which to commit crime. But it may also be the case that being active increases a person’s sense of purpose, which in turn increases the value of a life without crime—either because having a sense of purpose raises expectations of being able to engage in more interesting activities or jobs or because it reduces the discounting of future utility, or both. In either case, the expected value of a future without crime increases, which can be expected to reduce the propensity to commit crime.

As suggested by the correlations shown in Figure 1, a country’s increased spending on active labor market programs is associated with a reduction in crime. But because there are other plausible explanations for this negative association, it is not possible to infer from this finding alone a causal link from the rise in the spending to the drop in crime—for instance, through one of the mechanisms suggested above. Thus, the question is whether it can be shown empirically that the close association between participation in active programs and a lower propensity to commit crime can be interpreted as a causal relationship. Estimating such a causal effect presents several challenges. The main problem is to find a source of variation in participation in active labor market programs that does not directly, or indirectly through other channels, affect peoples’ propensity to commit crime. Furthermore, unobserved characteristics and events that make individuals more likely to participate in certain programs could also make them less likely to commit crime. The influence of these factors also has to be eliminated.

The evidence

Two empirical studies from 2012 and 2014 examine the causal impact of active labor market program participation in Denmark on crime [4], [5]. Another recent study on US data offers empirical evidence of an incapacitation effect from attending or not attending school for school-age youngsters [7].

The 2012 and 2014 studies use Danish register data with information on age, gender, education, labor market status, municipality, income, and criminal convictions for all residents (available from 1980), and information on participation in labor market programs (available from 1995). Using these data, the studies were able to compare the criminal activities of unemployed individuals who participated in active labor market programs with those of unemployed individuals who did not participate. If those who did not participate are found to have committed more crime, it would suggest that participating in active labor market programs reduces the likelihood that a young unemployed person will commit crime. Nevertheless, there could be other reasons why participants are more law-abiding. If, for instance, the better motivated unemployed with the best future prospects are more likely to enter active labor market programs, then the relationship just illustrates a known difference between more or less resource-rich people with respect to criminal convictions. This is called the selection problem.

The selection problem was diminished when Denmark made participation in active labor market programs mandatory in the early and mid-1990s for various groups of unemployed. Unemployed individuals are required to participate in an active labor market program of some kind (job-search courses, training, education, or relief work) for 75% of a normal work week in order to receive unemployment benefits. However, not all Danish municipalities implemented the new mandatory policy at once or with equal rigor. Thus, at any given time there would be comparable unemployed individuals in the country who were similar in terms of observable characteristics, including duration of unemployment, but only some of whom were in active labor market programs while others were not.

If this was the only difference between the two groups, then the crime rates of unemployed individuals in municipalities that implemented the requirement quickly could be compared with the crime rates of individuals in municipalities that implemented the requirement later in their unemployment spells. However, the way the municipalities implemented the requirement might not have been random, and there might be other reasons why the crime rate was lower among unemployed individuals participating in active labor market programs. For instance, municipalities with low crime rates might have implemented the requirement more rigorously because their unemployed clients were easier to work with.

To take account of such concerns—in order to also control for differences in unobserved characteristics between treatment and control groups—it is not sufficient to look at the difference between municipal crime levels. It is also important to look at the difference between two municipalities in the rate of change in the crime level as active labor market programs were implemented. If the crime rate declined more or rose less in the municipality that increased participation in active labor market programs, this would suggest that participation influences unemployed individuals’ propensity to commit crime.

Impact on unemployed welfare recipients without unemployment insurance

One study used this method, known as the difference-in-differences approach, to examine the effect of active labor market programs on unemployed welfare recipients—a group of unemployed people with a relatively high crime rate for whom the employment effect of the programs is particularly weak [4].

The study finally also had to deal with the lack of randomness in the allocation of unemployed individuals to active labor market programs (endogeneity). It did so by exploiting two types of policy change in Denmark [4]. First, it analyzed the effect of one city’s radical workfare reform. In 1987, the town of Farum introduced a requirement that all unemployed individuals without unemployment insurance who were receiving welfare benefits must enroll immediately in an active labor market program. (Unemployment insurance in Denmark is a public voluntary scheme, and workers who are uninsured are generally younger and the least productive workers. Uninsured individuals receive the less generous social assistance benefit.) In the rest of Denmark, participation in an active labor market program would normally not occur until individuals had received welfare benefits continuously for at least three months and usually much longer. Furthermore, participation was voluntary in the rest of Denmark until the beginning of the 1990s, and for most people until even later. Thus, Farum’s introduction of an immediate requirement to participate in an active labor market program can be used to examine the causal effect of participation on crime, using the rest of Denmark (where mandatory participation was introduced much later) as the control group [4].

Second, the study examined the effects of a series of national reforms of unemployment policy for young welfare recipients that were introduced in the 1990s and that strengthened the work requirement. The new requirements were introduced gradually, beginning with the youngest welfare recipients [4]. Thus, the study was able to exploit both the municipality-level differences in timing of implementation of the national reform and the differential introduction of the reforms across different age groups.

The analysis reveals that the reduction in unemployed individuals’ propensity to commit crime was a causal result of participation in active labor market programs [4]. The effect is economically significant: mandatory participation reduces crime rates by up to a third for young, unemployed welfare recipient men without unemployment insurance.

Unemployed recipients of unemployment insurance benefits

In a few regions in Denmark, municipalities conducted randomized experiments on the intensity with which newly unemployed individuals with unemployment insurance were required to participate in active labor market programs. The unemployed individuals in the treatment group were requested to participate earlier and more frequently in program activities. These experiments revealed that the programs had a significant effect on accelerating the employment of unemployed workers who were entitled to receive unemployment benefits, through a kind of threat effect [11].

The same experiment is used in another study to identify a causal effect of early and intensive participation in active labor market programs on the criminal activities of unemployed individuals [5]. Unemployed individuals who participated in intensive active labor market programs (the treatment group) were charged with fewer crimes and received fewer convictions than unemployed individuals in the control group, who were exposed to the standard, less intensive requirement. The effect on the number of convictions was a consequence of both the shorter unemployment spells and the more intense participation in active labor market programs while unemployed. The drop in the number of criminal charges was due entirely to shorter unemployment spells among participants in the more intensive program, who were re-employed more quickly. These participants committed less crime than unemployed individuals in the control group, but some of the reduction was due to the fact that the treatment group was reemployed faster, and people who are employed commit less crime than those who are unemployed. Altogether, they received 25% fewer criminal convictions than the control group.

Mechanisms through which active labor market programs reduce crime

These results reveal big and highly statistically significant effects and thus strongly suggest that an active labor market program reduces crime among the unemployed. The next task is to identify the mechanisms that bring this about. Apart from identifying an overall effect, one study also sheds light on what these mechanisms might be [4]. The study documents a direct effect for active labor market policies by using indirect information on whether people are working in regular jobs or are participating in relief jobs or some other form of activity through active labor market programs. Information on individuals’ income enables the study to take the income changes associated with program participation into account. The study also used data on the dates when crimes were committed to differentiate between the effect that participation in active labor market programs has on the amount of crime committed on weekdays and the effect on the amount of crime committed during weekends. Individuals participating in these programs have less free time to commit crimes during the week, but more free time over the weekend, when the programs are closed.

It is clear from these investigations that participation in active labor market programs reduces crime not only indirectly, as a result of more rapid re-employment (indicated by the reduction in welfare take-up), but also directly, among individuals who are still unemployed and enrolled in active labor market programs. Furthermore, participation in active labor market programs has a significant negative effect on crime during the weekend [4]. This result implies that the crime reduction is associated with positive changes in attitude or even lifestyle and is not simply the result of being occupied in program activities for part of the time. These findings suggest that the crime-reducing effects of active labor market programs could be long-lasting.

The effect of school enrollment on crime

For the younger members of the labor force, active labor market programs and school attendance have several characteristics in common: they are both intended to enhance qualifications and both require participants’ attention, or at least their time, so that they cannot engage in other activities while participating. Therefore, school attendance would be expected to have similar effects on young people’s propensity to commit crime. That is the conclusion of a US study of how crime rates for 16- to 18-year-olds vary across US states with variations in the states’ minimum school-leaving age [7]. The study controls both for the fact that there are time-invariant differences between the states (for example, in levels of income, levels of education, degrees of urbanization, and patterns of crime) as well as some differences in trends—some states are undergoing periods of positive development, while others are not. Taking all these factors into account, the study concludes that both property crime and violent crime fall when children in the oldest of youth cohorts are attending school. The study interprets this result as an incapacitation effect of schooling.

Other studies have shown that when school teachers are on strike, school students commit more property crime but less violent crime than when teachers are working [8]. The first effect is consistent with an incapacitation effect. The second is interpreted as a concentration/population density effect: when students are in school, they have many more interactions with their peers, and this increases the risk of getting involved in conflicts.

Limitations and gaps

The studies finding a crime-reducing effect of Denmark’s active labor market policies examined mainly special cases. Little is known about what program characteristics or activities generate the crime-reducing effects.

The main methodological challenges in isolating the effect of active labor market programs on crime from the general effect of unemployment are, first, to have random (exogenous) assignment of the unemployed to programs, to avoid selection bias, and second, to control for income. If participation in active labor market programs is associated with higher income among participants than among non-participants who are receiving unemployment compensation, the analysis has to be able to control for this. Two studies met these criteria: participation in the programs was mandatory (either by age or region or through lottery assignment), and the researchers were able to control for income [4], [5]. More studies are needed, however, also for other countries.

In many countries in Europe, active labor market programs now affect most workers at some point during spells of unemployment. Although the employment and wage effects of activation have been extensively researched, there are few studies of other types of effects. As should be evident from the studies discussed above, there are other aspects of active labor market policies that may well be of considerable importance to society, including their effects on criminality. In this regard, it would be useful to investigate which types of program are associated with the greatest reductions in crime among young unemployed individuals.

Even if the effects discussed above exist in other countries, as two studies indicate that they do [7], [8], the Danish active labor market programs are very expensive and might not be supportable in countries that do not have the same tradition of extensive public programs.

Summary and policy advice

There seems to be a clear crime-reducing effect of the active labor market policies that Denmark launched in the 1990s on reducing criminal behavior in unemployed men, especially those who are young, less well educated, and without unemployment insurance. Program participation in itself seems to directly reduce the propensity of unemployed individuals to commit crime, although active labor market programs might also reduce crime indirectly by accelerating re-employment to avoid having to participate in the program. Furthermore, program participants reduce their criminal activities both on weekdays, when programs are active, and on weekends, when they are closed, which suggests that part of the effect comes from a change in lifestyle induced by program participation.

Youth unemployment is a huge problem in the world today. While sometimes considered a temporary problem, it can have serious negative consequences for young peoples’ future labor market prospects. Unemployment can initiate a criminal career that becomes an attractive alternative to work in the formal labor market [2]. Economic crises with high unemployment cannot be avoided, but an active labor market program can mimic employment in some important aspects as a second-best option [4] and thus reduce the negative consequences of such crises.

The experiences of developed countries with active labor market policies have been mixed. While the overall effect has been higher employment, the average effect has been small compared with the cost [12]. Because it has been difficult to systematically document positive and economically significant effects of active labor market programs on employment or wages, at least in the short term (though the long-term effect looks better) [13], many countries have recently cut back on their programs. Nonetheless, there are clear indications that offering unemployed young people nothing at all is a very risky route to take.

The evidence strongly suggests that for young people, in particular young men, not being engaged or occupied in any formal activities is detrimental to themselves and to society, because being unoccupied increases their criminal activities. This is the case both because idleness provides the spare time in which to commit crime and because unemployed youths whose daily routines do not involve purposeful activities may lose the longer-term perspective that helps them understand the importance of staying out of trouble.

Crime prevention is social policy, and it does not necessarily have to be part of labor market policy. It is likely that the activities that prevent crime could be organized in another setting, where they could be better targeted and thus more efficient. And while it may turn out to be important that the activities offered to young unemployed people have a labor market connection, it is not yet possible to conclude that from the research. What is clear from the research, however, is that it is not advisable to leave unemployed youth entirely to their own devices.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author thanks Peter Fallesen, Lars P. Geerdsen, and Susumu Imai for collaboration on the main research behind this article [4].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Torben Tranaes