Elevator pitch

Female labor force participation is mainly driven by the value of women’s market wages versus the value of their non-market time. Labor force participation by women varies considerably across countries. To understand this international variation, one must further consider differences across countries in institutions, non-economic factors such as cultural norms, and public policies. Such differences provide important insights into what actions countries might take to further increase women’s participation in the labor market.

Key findings

Pros

Women’s economic activity outside the home translates into better outcomes for girls and women (improved health, reduced domestic violence for women), and society as a whole (greater economic growth).

Women’s labor market activity—not just entry, but also long-term attachment—provides the path for women to participate in the top ranks of academia, industry, government, and the non-profit sector.

Family-friendly policies (e.g. family leave and childcare subsidies) encourage women’s labor force participation.

Cons

Rising educational attainment by women does not always translate into increased labor force participation rates.

While family-friendly policies may encourage women’s labor force participation, they may also inhibit women’s advancement to the highest levels of their professions.

It is difficult to discern if rising educational attainment causes increased labor force participation, or if women’s rising labor force participation rates spur them to undertake additional educational investments.

Author's main message

Women’s labor market activity makes women and girls more economically valuable to their families and to society. While women’s labor force participation rates have risen in many countries, rates remain quite low in some countries and regions. In some countries, like the US, after a steady rise, rates have plateaued since 1990. Given societal benefits such as greater economic growth, governments have a compelling interest to undertake policies to encourage women’s labor force participation. Parental leave and childcare subsidies are two such examples.

Motivation

Women perform a substantial amount of unpaid work within the household, but it is paid work that translates into increased bargaining power in the household and raises families’ standard of living as a whole. The UN Millennium Goals laid out in 2000 underscored the crucial role of women’s paid labor market activity in enhancing economic development. These goals included “achieve universal primary education” (which is crucial, in that education is a key determinant of labor force participation) and “promote gender equality and empower women.” The latter was to be achieved by increasing women’s paid labor market activity, eliminating the gender gap in primary and secondary education, and increasing women’s political participation.

Considerable progress was made in achieving these goals by 2015, the target year, though the desired change is far from complete. Effective as of 2016, the UN established a new set of goals called the Sustainable Development Goals, with a target date of 2030. These goals explicitly include the following: “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Discussion of pros and cons

Benefits of women’s paid labor market activity for girls

Girls and women directly benefit from women’s paid work. At the most basic level, paid labor market activity has been found to increase girls’ chances of surviving from birth into adulthood and reduce the number of “missing women,” a phrase first used by Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen in 1990 [1]. “Missing women” refers to the number of women who would be expected to be part of the population in the absence of sex-selective abortion and gender discrimination, i.e. if girls were treated equally to boys. One example of the positive relationship between women’s economic activity and girls’ survival comes from a study that looked at the effect of economic reforms in rural China in the 1980s. These reforms spurred the production of tea, for which women have a comparative advantage (because they tend to be shorter in height than men and their fingers are more nimble). This study found that girls’ survival rates increased in tea-growing regions (where women’s labor was more economically valuable) relative to regions where men had a comparative advantage in production [2].

Women’s labor market activity is especially crucial for girls in countries where they are culturally less valued (e.g. in India and China, to name just two of the largest), and are thus at the greatest risk of neglect (e.g. lack of adequate nutrition or health care). When women gain employment, their families have more money to devote to these more culturally marginalized family members (girls). Evidence also indicates that mothers (and grandmothers) spend a larger share of their own resources on girls than fathers do. Thus, in countries that have traditionally favored boys, mothers’ employment is especially beneficial for girls in terms of basic survival, nutrition, and health [3].

Gender gaps in labor force participation (and education) have also been found to be negatively associated with economic growth [4]. Lack of progress in employment represents lost economic opportunity, because this valuable resource (i.e. women’s potential as labor force participants) is not being put to its best possible use. Put differently, women’s education and employment benefit society as a whole.

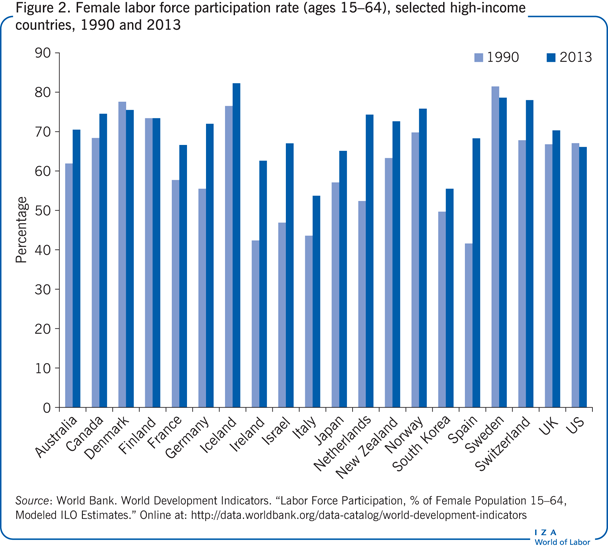

Evidence, patterns, and trends

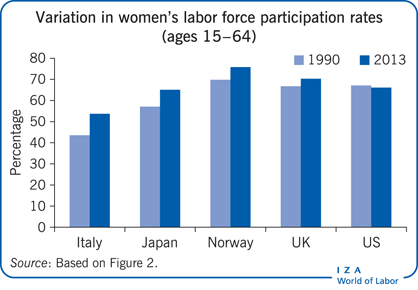

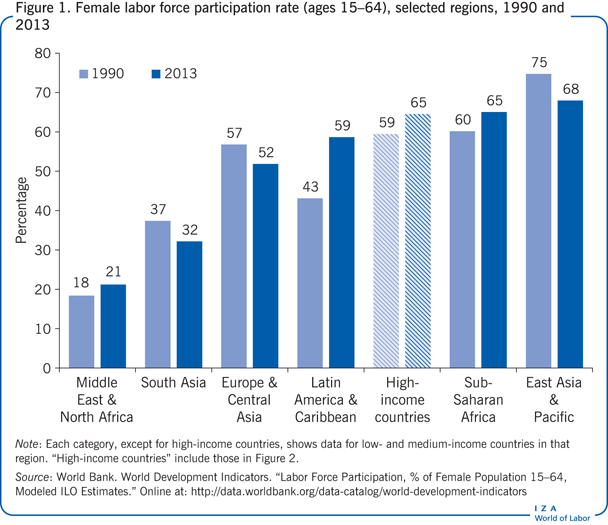

While it is not all that surprising to observe variation in women’s labor force participation around the globe (Figure 1), women’s labor force participation varies even among the set of economically advanced countries which are rather similar in many respects (Figure 2). This can be seen when comparing countries at a single point in time. While labor force participation rates generally, but by no means universally, increased between 1990 and 2013, the relative position of countries has changed. For instance, since the early 1990s, there has been no further increase in women’s labor force participation rates in the US, while rates in “peer” economically advanced countries such as Canada, the UK, and Australia have increased. As shown in Figure 2, this means that the US female labor force participation rate is now considerably lower than rates in a number of countries. One possible explanation, discussed later in this article, is that the US (increasingly) lags behind other countries when it comes to the adoption of family-friendly policies.

What factors determine women’s labor force participation?

A woman’s decision to participate in the labor force is fundamentally determined by two sets of factors: those that affect the wage she can earn in the paid labor market (i.e. her market wage) and those that affect the reservation wage (defined below) [5]. A primary determinant of the market wage is the level and quality of human capital, most notably education; this explains the focus of the UN Millennium Goals and the more recent Sustainable Development Goals on increasing educational attainment and reducing gender gaps in educational attainment. Another major determinant of the market wage is labor force experience (the total amount of time spent in the labor market), especially the amount of time spent with the same employer, known as firm-specific human capital. Women’s market wages also depend on the existing demand for their labor.

The reservation wage can be thought of as the value of one’s time spent at home or, alternatively, the wage at which a woman is willing to enter the labor market. This amount varies inversely with the husband’s income, and directly with greater availability of market substitutes for household production (e.g. purchased food and day care services) and household technology (e.g. the washing machine). The reservation wage is also affected by the presence of children, which is itself determined by the accessibility to and affordability of birth control. Other determinants of the reservation wage include broader social norms as well as the family’s preference for home versus market produced goods.

Finally, women’s labor force participation is affected by government labor market, tax, transfer, and family policies, as well as by employer policies, which are discussed later on.

What explains differences in women’s labor force participation across countries?

To explain the variation in female labor force participation—not only across, but also within regions—one needs to consider a broader set of factors. These include, but are not limited to, non-economic factors (e.g. political ideology, differences in cultural expectations, and religion), the prevailing industrial mix and relative demand for female workers, stage of economic development, institutional features including differences in wage setting (more or less decentralized economic system), and differences in policies (e.g. labor market, tax and transfer, and family) [5], [6].

Turning to non-economic factors first, one can look to religion; in Catholic countries such as Italy and Muslim countries such as Egypt, which tend to be more patriarchal, women’s labor force participation rates tend to be lower. Political ideology also plays a role, as seen in the high rates of female employment in the countries of the former Soviet Union. Another factor is gender expectations about women’s and men’s appropriate roles in the household and the family. For instance, if the prevailing attitude is that the “husband should be the breadwinner and the wife should be the homemaker,” rather than a more egalitarian view, one would expect women to have a lower labor force participation rate in that type of society. Related to this, if the allocation of time in the household is very unequal, with women bearing the major responsibility for taking care of home and family, this burden is likely to lower their ability to participate in the paid labor force. Furthermore, even if women in those situations are employed, their attachment to the household likely affects the type of job they hold, the number of hours worked, and, in turn, their prospects for career advancement.

One must also look to differences in the industrial structure of the economy to explain variations in women’s labor participation across regions. A larger service sector, such as in the US, provides more substitutes for home production (e.g. home-produced meals, childcare) and offers greater opportunities for part-time employment, both of which are factors that facilitate women’s entry into the labor force. A larger public sector also tends to provide more opportunities for female employment.

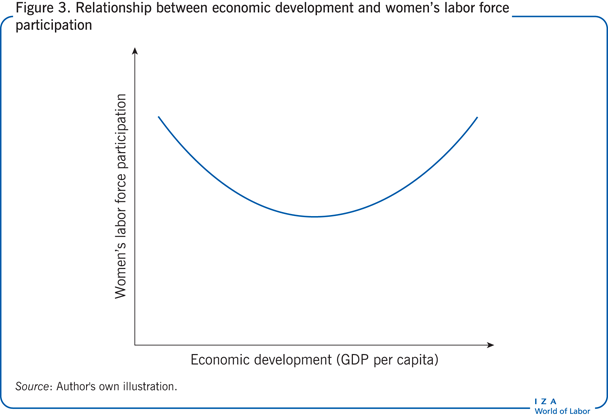

Another factor related to women’s labor force participation is the country’s stage of economic development. There is a sizable body of literature that points to a “U-shaped” relationship, according to which women’s labor force activity is very high in the early stages of economic development as they tend to participate in subsistence agriculture, declines as the economy becomes more manufacturing-based, and then increases again as women gain education and move into white-collar jobs (Figure 3). For the US, the upturn in the “U” is explained by the increased demand for clerical workers in the first part of the 20th century [7]. For a more recent example, studies point to the dramatic growth of IT “call centers” in India as having a similar impact on women’s labor force participation rates there [8].

As noted, labor market, tax, transfer, and family policies also matter. For instance, labor market policies aimed at ensuring equal opportunities for women in the labor market such as anti-discrimination laws and policies targeted at advancing women to top positions such as corporate board quotas (requirements that women hold a specified percentage of board member positions) are expected to positively influence women’s decisions to participate in the labor market. Turning to tax policy, the structure of the income tax in a number of countries creates a “secondary earner penalty,” whereby the labor market return for the secondary earner (typically the wife) is lowered, thereby discouraging women’s labor force participation. For instance, the US and Germany are two of only a handful of economically advanced countries that have a tax structure where the family is considered the unit of taxation. A progressive tax code combined with this tax structure creates a secondary earner penalty because a wife’s first dollar of earnings is taxed at the top rate of her husband’s last dollar. In fact, even in countries where the individual is the unit of taxation, the income tax structure may still impose a secondary earner penalty if there is a dependent credit or allowance that is reduced or eliminated when a spouse enters the labor force or increases his/her number of working hours [9]. Other tax policies, such as the earned income tax credit in the US, encourage women’s labor force entry by providing an earnings subsidy for low-earner families.

The role of family policy in increasing women’s paid labor market activity

One lever to encourage women’s labor force participation is the adoption of policies that help workers, especially mothers, who remain the primary caretakers of children, to better balance paid work and family. Focusing on the OECD countries, the most generous of these policies are offered by the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) [6], [10].

In terms of leave, all OECD countries except the US offer some form of paid family leave. Family leave is typically offered as some combination of maternity leave, paternity leave, and parental leave (leave that can be taken by either parent). These policies vary considerably across countries with respect to leave duration and the replacement rate that is paid in lieu of the parent’s former wage. Just looking at variation in the duration of paid leave, Sweden offers as much as 15 months while the US offers no federal paid leave (and only provides 12 weeks of federal unpaid leave).

Mothers are much more likely than fathers to make use of available leave policies. Leave policy gives workers the opportunity to return to their pre-leave job/employer, which; raises labor force participation rates and helps workers retain firm-specific capital that subsequently translates into higher wages. However, such leave policies—if overly generous—have the potential to work against women, as discussed in further detail below.

An innovative type of leave is called a “father’s quota.” Nordic countries first initiated this type of leave in the 1990s, and have since extended its length. For instance, in Norway the leave has been expanded from four to ten weeks. It has also been adopted in Quebec, Canada, among other places. The unique feature of a father’s quota is that it is designed as a “take it or leave it” type of offer. In other words, unlike the case of parental leave, the quota leave time cannot be shifted to the mother. This design encourages fathers to take the leave and reduces the stigma of doing so since it is specifically put in place for them. As fathers take (longer) leave to care for children, thereby (more fully) sharing the responsibility with mothers, this policy should increase gender equality in the workplace. Fathers’ increased time spent with children is also expected to have positive impacts on their children’s development [10].

Another policy that unambiguously supports women’s labor force participation is childcare assistance, either via publicly provided childcare or through government or firm subsidies. Again, there is considerable variation across countries. The percentage of GDP devoted to childcare for infants through the age of three is highest in Sweden and Denmark while, in sharp contrast, the US is among the least generous [6]. In the US, childcare assistance is largely provided through tax credits, and for children in lower-income families, some funding is available through federal block grants and an early childhood program called Head Start.

The extent to which both female and male workers are able to share the responsibility of caring for children, elderly parents, and the household is improved by policies that support workplace flexibility, either through part-time work or by means of an innovative policy adopted in some countries that gives workers the “right to request” flexible or reduced hours. As with “too much” paid leave, these policies also have potential downsides for women in the labor force, as discussed shortly.

Employers may also offer other policies that help facilitate women’s labor force participation (and, in fact, help all workers better balance the dual demands of paid work and family). One such policy is “flextime.” This type of policy allows workers to make changes such as shifting the starting or ending time of the workday, or permits workers to work more hours over fewer days. With the rise of computers and other advancements in IT, another policy that provides greater flexibility is telecommuting or home-based employment [5]. To promote gender equality in the workplace, it is important that employers encourage both women and men to utilize these options.

One recent study, which looked at women’s labor force participation in 22 OECD countries, found that women’s participation rates in the US fell from sixth highest in 1990 to 17th in 2010. This fall can be attributed to the fact that the US lagged behind in the adoption of federal-level family-friendly policies; if the US had adopted the average set of policies that were implemented in the other countries examined then its relative position in 2010 would have stood at 11th [11].

Still, policies to help balance women’s paid work and family can negatively affect their career progress and must be weighed against their benefits [11]. For instance, leave that is “too long,” say a year or more, may encourage workers to remain away from their jobs longer than they might otherwise have done, thereby reducing their human capital, and in turn, limiting future opportunities for career advancement. Part-time work is also problematic; while it keeps women in the labor market, it is full-time employment that is the necessary (albeit not sufficient) key to moving up the career ladder. Moreover, these types of policies may have contributed to the presence of a “glass ceiling,” a set of subtle barriers that inhibit women’s career advancement [5]. For instance, in Sweden, which provides a long period of paid leave, women tend to be disproportionately employed in “female” white-collar jobs in the public sector, which offer fewer opportunities for career advancement. Further, if the length of parental leave is too long or if the “right to request” flexible hours is too costly, firms may avoid hiring women, especially for positions high up on the career ladder that involve a long-term full-time commitment.

Women’s rising educational attainment, labor force participation, and prospects for career advancement

Women’s labor force participation rates have been found to be strongly positively associated with rising educational attainment [5]. What is especially striking is that women now make up a larger fraction of college students in all economically advanced countries, and also in some developing countries. The positive association between educational attainment and labor force participation could be due to one of two reasons: women who invest in education are those most likely to enter and remain in the labor force in order to recoup their return on that investment; or, women who anticipate long labor force attachment are most likely to pursue higher education. One notable exception to this pattern is the Middle East and North Africa. In these regions, women’s rising educational attainment has not generally translated into higher participation rates. One recent study points to limits placed on women’s mobility resulting from concerns about safety and “purity” [12].

For married couples in the US, as well as in a number of other economically advanced countries, studies have found that women’s labor force participation rates are quite high even for college-educated women married to college-educated men [13]. This points to the strong “pull” of women’s own labor market opportunities; the pull is strong enough that it offsets the effect of their husbands’ high earnings, which serves to increase their wives’ reservation wage.

Rising women’s labor force participation is the crucial first step in women’s advancement. Labor market experience is critical for developing the skills necessary to advance up the ranks professionally, whether in government, industry, nonprofit, or academia. General labor market experience is valuable, and beyond this, if workers remain with the same employer, they gain additional valuable firm-specific human capital. However, it is still the case that equally qualified women—those with the same level of labor market experience and similar other measured human capital—remain underrepresented at the upper echelons of industry, government, etc., pointing to differential employer treatment (i.e. labor market discrimination) [5]. This suggests the need for policies to facilitate women’s ability to climb the corporate ladder. In addition to family leave and childcare subsidies, such policies might include the stronger enforcement of anti-discrimination laws and corporate board quotas.

Limitations and gaps

International comparisons of labor force participation rates must be regarded with some degree of caution. First, the age distribution of the population differs across countries, and so does the age distribution of the labor force. Individuals aged 25 to 54 (typically regarded as the “prime age” for employment) are the group most likely to be in the labor force. If more women are in this age range in a particular country, this should lead to higher female labor force participation rates, all else being equal. Countries may also differ with respect to the age at which young people usually enter the labor market, which partly depends on college attendance. Additionally, countries may differ on the age at which older people typically exit the labor market, which partly depends on access to retirement funds or familial support.

Second, as with many relationships, it is difficult to disentangle causation from correlation. Is it the case that women’s educational attainment spurs labor force activity, or is it rather women’s anticipated degree of labor force attachment that leads to educational investment? A similar set of issues arises when thinking about the relationship between fertility and female labor force participation. The presence of small children deters labor force participation because they increase the value of home time, and hence, the reservation wage. On the other hand, one would expect that as female labor force participation (and the associated wage) increases, the opportunity cost of having children also rises, thereby reducing the demand for children. As a final example, cultural attitudes such as the view that “men should be the breadwinner and women should be the homemaker” clearly discourage women’s labor force participation. However, increased labor force participation by women likely helps alter prevailing attitudes about what are considered appropriate roles for both males and females. The implication of this discussion is that researchers need to utilize research methods that can clearly identify the direction of these relationships.

Summary and policy advice

Women’s labor force participation rates are largely rising across the globe, which bodes well for women, children, families, and society. However, progress is clearly very uneven, and rates have even plateaued in the US. Family-friendly policies represent one lever that can be used to increase women’s participation. Father quotas seem to be an especially promising policy. However, in selecting the mix of family policies, policymakers must be careful to recognize that the benefits of some family-friendly policies such as longer paid maternity and parental leave and the “right to request” flexible hours may have unintended negative consequences for women’s career advancement. It is also the case that women continue to bear greater responsibility for care of the home and family. Child care subsidies are one way to reduce this unequal burden, and in turn, facilitate women’s labor force participation and career advancement.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [5].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Anne E. Winkler