Elevator pitch

The importance of benefit portability is increasing in line with the growing number of migrants wishing to bring acquired social rights from their host country back to their country of residence. Failing to enable such portability risks impeding international labor mobility or jeopardizing individuals’ ability to manage risk across their life cycle. Various instruments may establish portability. But which instrument works best and under what circumstances is not yet well-explored.

Key findings

Pros

Benefit portability promises to lift a major constraint on international labor mobility and individual risk management.

A number of promising instruments exist to establish benefit portability across borders.

Bilateral social security agreements are traditionally considered the key portability instrument and seem to work well.

Recent innovations include the redesign of benefits that separate pre-saving and redistribution aspects, and the use of multinational private sector providers.

Cons

The labor market aspects of benefit portability remain poorly understood.

It is unknown whether a lack of portability is actually relevant to international labor mobility; the limited effect on one’s ability to manage risk may be compensated for by higher wages in the host country.

Bilateral agreements currently only benefit a small share of migrants, mostly those moving between rich countries.

Understanding of the actual working and effectiveness of portability instruments is limited.

Author's main message

More and more individuals are working abroad temporarily. These migrants want to acquire benefit rights while working abroad for use later in life, such as retirement pensions. Migrants who move without benefit portability forgo their acquired rights/savings, reducing both their ability to manage risk and their welfare. Bilateral cross-country agreements have proven effective in establishing portability for some migrants. Portability may be improved via benefit redesign, additional cross-country agreements, and the use of multinational providers. However, understanding of how these instruments work and of their effectiveness is still limited.

Motivation

The portability of international migrants’ social benefits is gaining attention across the world. Portability was recently considered as a performance indicator for the UN Sustainable Development Goals [1], but was ultimately dropped as the assignment of a relevant single instrument proved difficult. Interest in this topic is due to the increasing number of individuals who spend at least some part of their life abroad, working and acquiring benefit rights that they want to preserve when returning home or moving on to another country of work or residency. The labor migrant-driven demand for cross-border portability [2] is joined by the more recent retirement migrant-driven demand [3], both of which are critical outcomes of globalization [4].

How to best establish cross-border portability is still an open question. Bilateral social security agreements (BSSAs) between migration corridor countries are often considered the best approach. Yet only about 23% of the world’s migrants move between countries where BSSAs exist; establishing such agreements is difficult; their scope of benefits and actual performance are largely unknown; and complementary and substitutive approaches might lead to more effective portability. But, does a lack of benefit portability actually hinder labor mobility between and within countries? Or, does it have more of an impact on individuals’ ability to manage risk across their life cycle?

Discussion of pros and cons

Relevance and trends

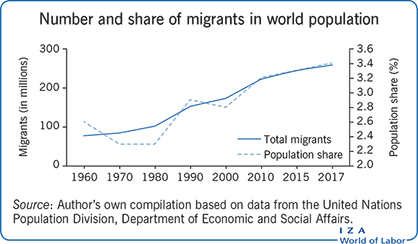

As of 2017, 3.4% of the world’s population lived outside their home country (up from 2.3% in 1980), equating to approximately 258 million people (see the Illustration). At the beginning of 2016, 20.7 million people who were citizens of non-member countries lived in the EU28, representing 4.1% of the EU28 population; meanwhile, 35.1 million people living in the EU28 were born outside of the EU. Also in 2016, 16 million people were living in one EU member state while holding citizenship in another.

While these migrant stock numbers may be impressive, they actually underestimate the underlying labor mobility dynamics; i.e. the increasing number and share of people who have or will spend at least part of their working or retirement life outside their home country. This development is difficult to quantify because individuals often embark on multiple migration spells of varying length, sometimes to multiple countries. Nevertheless, strong indications across the world suggest that the number of spells spent abroad is rising. In the EU, the number of citizens who spend at least some of their adult life living outside their home country (as a student, intern, intra- or inter-firm mobile employee, labor migrant, or “snowbird” retiree—those retirees who migrate to warmer climes in the winter) is increasing and may soon reach one out of every five individuals. In Germany, for example, pension payments to and from abroad amounted to about 11.1% of the total number of pensions paid in 2013, up from 9.8% in 2005.

Defining portability

Cross-border benefit portability is understood as the migrant’s ability to preserve, maintain, and transfer both acquired social security rights and rights in the process of being acquired from one private, occupational, or public social security scheme to another, independent of nationality and country of residence [5]. Social security rights refer, in principle, to all rights stemming from contributory payments or residency criteria in a country. Benefits that are not typically portable are those that are not based on contributions, such as benefit top-ups for low-income individuals or minimum income guarantees.

Preserving, maintaining, and transferring acquired social security rights between schemes is often limited or simply not possible within countries. For example, in many countries, a worker’s rights within a civil service scheme cannot be preserved when moving to the private sector, or the acquired rights are reduced when transferred to the private sector scheme. Similarly, private sector health care provisions are often not transferable when one moves between US states or between EU member countries. Hence, the request for full portability of social benefits for migrants moving between countries that are far apart geographically needs to be seen in perspective and expectations managed, as trade-offs will exist and choices have to be made.

Select conceptual considerations

Three key dimensions of interest in portability

Establishing social benefit portability should be a clear priority, as three key considerations—economic, social, and human rights—favor it [6]:

From a first-best economic point of view, an individual’s labor mobility should not be influenced by a lack of portability of social benefits.

From a social policy point of view, such acquired rights are a critical element of an individual’s (or family’s) life cycle planning and risk management strategy. Denying portability—particularly after the irreversible decision to move has been made—hinders individuals’ and families’ abilities to plan for the future and may create substantial welfare losses.

From a human rights point of view, individuals have the right to social protection according to national legislation and international conventions, and acquired rights should carry over when they leave a country or profession. A key question is whether these human rights apply only to acquired (contributory) rights or to all social rights, however financed. As these rights are resource-consuming, economic and human rights trade-offs will emerge.

Why is portability difficult to establish?

In all countries, internationally immobile labor dominates mobile labor in both volume and influence; thus, political support for cross-country portability is typically limited. Proposed considerations for the design and implementation of portability schemes have only slowly been incorporated into national and international legislation, following the rise in cross-border labor mobility. Even today, domestic considerations are prioritized unless they contradict, for example, ratified ILO conventions or EU regulations [6].

The technical reasons for limited portability are essentially linked to the incomplete insurance nature of benefit determination in social security schemes. Such schemes do not allow a straightforward split of acquired rights into: (i) a contemporaneous insurance component that is consumed right away and hence incurs no portability issue; (ii) a pre-savings component inherent in all social benefit systems that could be portable if its value could be easily established and transferred; and (iii) a potentially massive redistributive component within and between benefit cohorts (as in pension and health care schemes). This redistributive character of benefit schemes is responsible for the long vesting periods that internationally mobile workers may not fulfil in a single country, but could easily satisfy if the insurance periods in all countries in which they acquired rights were added up (i.e. totalized, as done in country agreements).

For which benefit types should portability be established, and based on what criteria?

Social security covers both social insurance and social assistance programs. The difference can be framed through their financing—individual contributions versus general government revenues—but is also related to how they lend themselves to risk/insurance considerations or reflect general redistributive and anti-poverty agendas. Main social security benefits to consider for portability include: old-age, disability, and survivors benefits; workers’ accident and occupational disease insurance; unemployment benefits; sick pay and maternity benefits; family/childcare benefits; and health and long-term care benefits.

Benefits may not all be equally important from a social risk management perspective, and not all distort mobility decisions in a relevant manner. For both considerations, the long-term benefits—old-age and health care—may be the most important ones. They involve the most important risks, the highest savings component, and often the largest redistributive volume. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine the risk situation abroad (e.g. unemployment), the actually eligible recipients (e.g. number of children), or prices (e.g. long-term care costs). It can be conjectured that a cost–benefit analysis may recommend establishing portability of a limited benefit package for a limited set of countries with strong labor market connections and bidirectional labor flows [6].

Policy options to establish portability

Three main approaches can be used to establish portability: (i) changing the benefit design to make benefits as portable as possible without government action; (ii) establishing portability arrangements unilaterally, bilaterally, and/or multilaterally; and (iii) using multinational private sector providers [7].

The critical feature in revising benefit design is to differentiate explicitly between the contemporaneous insurance component (which does not need portability) and the pre-savings component of social benefits (to be made portable), in addition to making any redistributive action outside the benefit scheme (so that no portability issues within the scheme emerge). Having a clearly identified pre-savings component should substantially ease portability for all social insurance-type benefits (except, perhaps, family benefits). For cash benefits, identification of the pre-savings component is naturally facilitated by the move from a defined benefit to a defined contribution-type structure. Benefits based on defined contributions are inherently more portable within and across countries as accumulated resources can be more easily transferred with the migrating individual into their new host country’s scheme.

A number of government-sponsored portability arrangements can improve or even fully establish benefit portability. The portability discussion typically focuses on BSSAs, but the range of actions is much larger and includes the following:

Unilateral actions can be taken by a country where individuals have established acquired rights. Such one-sided government actions can establish partial portability through full exportability of benefits in disbursement. It could go further and potentially grant prorated rights and payments if the vesting period is not reached.

BSSAs represent the current cornerstone of portability arrangements between two countries. While bilateral arrangements can theoretically address the whole scope of exportable social benefits, BSSAs typically focus only on long-term benefits, such as old-age, survivor, and disability pensions. They focus to a much lesser extent on health care benefits, and outside the EU, family and unemployment benefits are typically not portable.

Multilateral arrangements (MAs) represent a general framework of portability for a group of countries for all or a subset of social benefits. These general agreements are typically operationalized by more detailed BSSAs. The most developed MA is the one among EU member states (plus Norway, Lichtenstein, and Switzerland) that is not actually an MA, but rather based on supranational EU law. Traditional MAs were established in Latin America (MERCOSUR) and the Caribbean (CARICOM); one was recently established between Latin America and Spain and Portugal (Ibero-American Multilateral Convention on Social Security; CMISS) and one among 15 French-speaking countries in Africa (CIPRES); yet another is under development for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries. Multinational portability ambitions are also expressed in the Southern African Development Community (SADC), which comprises 15 member states.

Multinational providers (MPs) are a very promising approach to establish portability, but are often overlooked. MPs use the services of private sector providers, at least for supplementary benefits in health care and retirement income. MPs exist and function well for health care benefits (e.g. Cigna services World Bank staff and retirees residing in Europe and is used by the European University Institute). MP arrangements are also selectively implemented for supplementary funded pensions of international workers in large multinational enterprises.

Scope and trends of portability regimes across the world

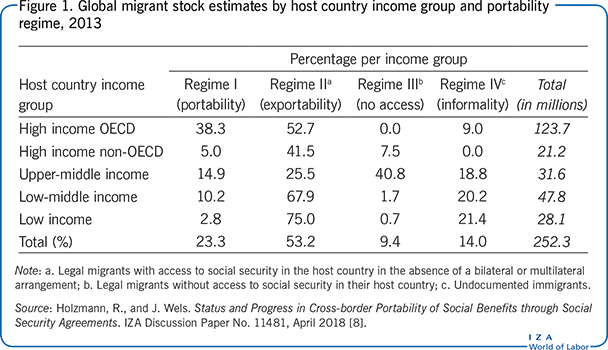

Figure 1 shows the most recent estimates of the relevance of the four main portability regimes by countries’ income group in 2013 [8]. Regime I (“portability”) indicates the existence of a BSSA in the host country, independent of its actual content, though it will typically cover at least pension benefits. Regime II (“exportability”) includes regular migrants living in host countries that have no BSSA with their home country but allow, in principle, cash benefits to be exported once eligibility is established; rights under establishment may not be covered but may be accessed after retirement. Regime III (“no access”) indicates documented migrants in host countries with no access to national social insurance programs, which means they have no mandated contribution obligation but also no pension or other benefits upon return. Regime IV (“informality”) offers an estimate of the share of migrants who are undocumented in the host country, with no or no valid contributions to pay and thus no benefits to return home with.

In 2013, only 23.3% of the total stock of migrants in the world was subject to BSSAs (Regime I). Of this favored group, the large majority (80.5%) were migrants from high-income countries living in other high-income countries. The majority of migrants (53.2%) lived and worked in countries that allow cash benefits (Regime II), once established, to be exported, but this is often restricted to pension-related benefits. However, eligibility among this majority group may never actually happen, as many countries have waiting periods of 10, 15, or more years. About one in ten (9.4%) migrants were not allowed to join the national system in 2013 (such as in Saudi Arabia and Singapore), but did not have to pay contributions either (Regime III). An estimated 14.0% were undocumented migrants (Regime IV).

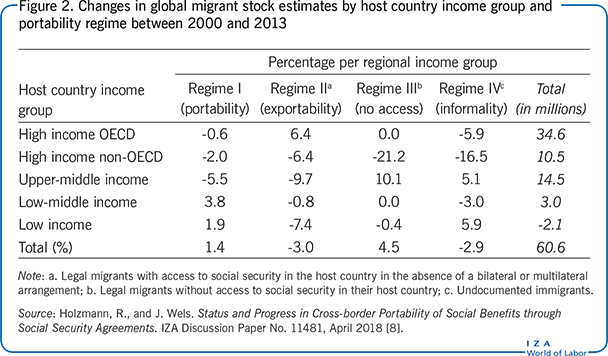

Figure 2 compares the results for 2013 with those of 2000. The total change in migrants included under Regime I indicates a moderate aggregate improvement of 1.4 percentage points, but this masks the much larger effect on migrants from low- and low-middle-income countries. The pure exportability Regime II and the informality Regime IV are both in retreat, with reductions of 3.0 and 2.9 percentage points, respectively. The largest change takes place for Regime III, under which migrants have neither access to the national pension and health care schemes, nor the requirement to make contribution payments. This latter group can manage their own retirement savings and health care provision in their home country, where remittances are a major contributor to poverty reduction and a source of foreign exchange. Most of the 4.5 percentage point change includes migrants toward upper-middle-income countries, due primarily to the expansion of managed migration programs between Asian countries and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, but also Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and South Korea.

Do BSSAs actually work?

Despite the still limited scope of their cross-country applicability, BSSAs are the workhorse and most popular choice for promoting benefit portability. However, despite the strong support of many social scientists, little rigorous evidence as understood by economists exists about their actual working. Do they really deliver what is expected, and by what criteria is the envisaged outcome measured?

To explore the delivery of BSSAs between EU and non-EU countries in relevant migration corridors, a World Bank-sponsored project undertook four migration corridor studies [7]. The Austria–Turkey, Germany–Turkey, Belgium–Morocco, and France–Morocco corridors, all well-established migration corridors, were selected to reflect similarities and differences. This allowed for the first-ever qualitative and partially quantitative insights into BSSAs’ working and led to recommendations for policy reforms and next research steps. Three broad criteria were used to assess whether portability arrangements succeed in terms of fairness and efficiency considerations:

Individual fairness for the mobile worker—no major benefit disadvantage or advantage arises with regard to pension and health care for migrants and their dependents.

Fiscal fairness for host and home countries—no country is advantaged or disadvantaged.

Bureaucratic effectiveness—for both individuals and countries.

The overall conclusions from the four investigated corridors are quite encouraging, though there is room for improvement. The BSSAs seem to be working reasonably well overall, with only a few areas of contention and jointly recognized areas for improvement. With some exceptions, this assessment essentially holds well for two of the three criteria used to evaluate the BSSAs [7].

Individual fairness

BSSAs do not create any major benefit advantage/disadvantage that risks affecting labor mobility on a large scale in any of the four corridors. Implementation of full health care benefits for mobile workers between France and Belgium and France and Morocco will close a remaining relevant benefit gap. The BSSAs offer pension portability for mobile workers, with no major issues around the lack of benefit take-up. Nevertheless, a few important outstanding issues remain, particularly the nonportability of noncontributory pension top-ups, requests for retroactive payments lost due to late application and long administrative processes in the home countries, and (for the Francophone corridors) the handling of Muslim repudiation/divorces and widows benefits. Family allowances remain an issue of discussion with regard to beneficiary numbers and benefit levels, and different approaches across the corridors may continue to prevail.

Fiscal fairness for countries

The evaluation of this criterion was mixed or at least uncertain. In all four BSSAs investigated, the increasingly closer contribution/benefit link helps in the pursuit of fiscal fairness, at least in principle. However, high and often increasing levels of budgetary transfers to keep pension schemes afloat have an opposite effect. For health care systems, it is largely unclear whether and to what extent fiscal fairness is or can be achieved under the current responsibility, cost determination, and reimbursement structure, or how important unfairness is. Major research is still required in this area [9].

Bureaucratic effectiveness

Interviews with stakeholders or their associations gave all EU host countries’ institutions high marks for their provision of benefit-related information and services but had a less favorable assessment for their home countries. A concern for many applicants is the delay in processing, which may lead to benefit losses. The advantages of advanced electronic file preparation and transfer in EU countries are attenuated by the paper-based information collection systems and transfer in Morocco and Turkey; the situation is further aggravated by frequent verification issues for names and birth dates. Electronic file exchange systems across BSSAs are envisaged and may soon take place in some corridors.

Of course, these results hold only for the four corridors investigated and cannot be generalized.

Research issues and policy questions

Does portability or its absence actually matter?

If so, does it matter for labor mobility such that individuals (i) do not migrate because social rights acquired in the host country are not portable or (ii) do not return to their home country because they would lose some or all of their benefits? Or does it have only small effects on labor mobility, as migrants do not know about the benefit loss or are willing to accept it, as the expected earnings gained through migration dominate the decision? The findings in the few available corridor studies are consistent with sparse empirical evidence that migration decisions may only be marginally influenced by the presence or absence of portability. For example, no implemented BSSAs exist between Mexico and the US or between Asian and Gulf Cooperation Council countries, but these are the largest migration corridors globally. This suggests implications for the risk management of migrants (who must undertake their own risk provision) and for home countries motivated to offer special arrangements (such as health care provision by Mexico for families left behind and a range of support programs by the Philippines).

Portability arrangements seem to have some limited yet essentially unquantified effects on return migration, although some features of pension and health care provisions may make many migrants stay in the host country and not return. In terms of pensions, top-ups and other advantages for low-income retirees seem to matter most (e.g. free TV, telephone, and public transport services for low-income elderly), while for health care, access to high-quality care seems to be important. It would be interesting and relevant to experiment with limited portability of top-ups and/or selective access to health care in former host countries for return migrants to explore the return mobility effects. It may be that economic considerations actually matter very little compared to proximity to one’s grandchildren or to purposeful distances from estranged families after many decades abroad.

Should differences in cost-of-living be reflected in the level of transfers made abroad?

This accommodation is already taking place for reimbursement of health care costs for family members or retirees living abroad (inside and outside EU countries such as Turkey and Morocco). Such costs incurred are typically reimbursed at the level of actual individual costs or some flat-rate average costs. This kind of adjustment was under discussion for child allowances before the Brexit referendum in the UK, and is under discussion in Austria and Germany for allowances sent to Bulgaria, Hungary, or Poland. Allowances for two children amount to a major share of local wages in the home country and may create labor market distortions similar to a wage subsidy in the host country. How the European Court of Justice will decide between the request for equal treatment of EU citizens, thus disallowing differentiated benefit levels, and the rejection of subsidies and market distortions will be interesting. If differentiation is allowed, it will also have to apply to the children of nationals living abroad. In a case concerning the payment of military pensions to former soldiers in Africa, the French Constitutional Court saw little issue in the payment of lower benefits to countries with lower costs of living, but it did not allow differentiation by nationality.

What do the findings mean for lower-income countries?

For a lower-income country, the necessary conditions for establishment of a BSSA are:

A sizable migration corridor with the host country (otherwise the fixed costs associated with a BSSA are too high) that offers its migrants access to both sending and receiving countries’ social security systems (otherwise neither home nor host country will be interested, as there is nothing to agree upon, such as with the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, Malaysia, or Singapore);

Its own functioning social security system or at least one or two well-operating schemes (otherwise return migrants have no easy way to channel their applications to host countries and consequently may have less interest in participating in a scheme while working abroad). Broad similarity of schemes between host and home countries will help to facilitate establishment of a BSSA and to calculate the benefits due; and

The schemes put in place should be computerized (ideally with a unique personal identification number), should have access to recorded birth and death certificates in the home/return country, and should provide a system to take care of migrants as they prepare for departure, during their stay, and upon their return.

Should lower-income countries pursue a limited or an ambitious approach to BSSAs?

A limited negotiation approach with a focus on a few critical benefits has a much higher chance of early success—particularly if the focus is on work injury, pensions (old-age, disability, and survivors), and health care for family members left behind and visiting the host country. Renegotiating a BSSA for enhanced benefits (such as family allowance and health care in retirement) is possible when the migration corridor is more heavily utilized and domestic equivalents are created, but the process of renegotiation and implementation will likely be lengthy. Pushing for a comprehensive BSSA and broad benefit coverage from the start, as within the EU, may not be feasible and is only justified in very dense migration corridors. Current signals from EU countries indicate a reluctance to engage in a broad mandate and in particular to include comprehensive health care in future non-EU country agreements.

Are funded private sector provisions more portable?

Intuition might suggest “yes,” as actual money instead of abstract acquired rights may seem much more fungible. But closer inspection suggests this is not necessarily the case, and would only be relevant for long-term contingencies such as retirement and health care. Private saving offers a first defense against many financial risks in life, and money should be easy to carry when moving from country to country. However, finding reliable financial institutions at home and abroad to park the money remains a challenge. In addition, private sector pension arrangements often profit from tax privileges during the accumulation phase; host countries increasingly want to recoup this when the migrant leaves the country, which may entail a sizable exit tax [10]. Private health care insurance is not easily portable between countries (and even within countries), so sizable savings elements are typically lost when moving. Even within the EU and the US, private pension and health care provisions are much less portable than public and mandated options. This situation has led to the development of pan-European and international private programs in health, with similar steps being taken toward establishing a pan-European supplementary pension benefits fund. However, progress has been limited so far.

Limitations and gaps

Portability of social benefits is a new topic for economists. This area—like the taxation of cross-border pensions—was for decades the domain of the legal profession and remains largely unexplored territory [11]. Social scientists have shown increasing interest in migrants’ access to social benefits, but the labor market aspect remains poorly understood [12]. Very few evaluations have been conducted on the workings of the key instruments that could make portability a reality, and all available studies have been largely qualitative, as the data for a quantitative evaluation are not easily accessible (as they are housed in social security institutions). This represents a rich field of study for researchers interested in both social protection and labor market issues. While future quantitative work on the topic will be crucial to guide policymakers in their decisions, a much better understanding is still needed about the actual structure, content, and processes of the key portability instruments—i.e. benefit redesign, BSSAs and MAs, and MPs. This will create a major challenge, as the request for better migration data is augmented with the request for social security data along individuals’ life cycles from both their home and host countries.

Summary and policy advice

Benefit portability issues have slowly gained policymakers’ attention. This interest is likely to grow as the number and share of individuals in the world for whom the topic matters are increasing. However, there is a lack of sound research in the associated conceptual and empirical issues. As a result, it is difficult for policymakers to fully understand the potential options and trade-offs or to obtain relevant guidance for their policy decisions. Against this background, policymakers should consider the following three pieces of advice:

Invest in a review of instruments currently in place, particularly with respect to the performance of BSSAs. Such a review is best done against a conceptual benchmark and would benefit from international collaboration, or at least information sharing.

Explore alternative portability designs, i.e. benefit redesign and multinational private sector providers. Both are highly promising instruments and may prove to be formidable complements and/or substitutes to BSSAs and MAs. They also bridge the public, occupational, and private provision divide.

Gather better migration data—stocks and flows—and provide better access to anonymized social security data. Access to data is still the exception rather than the rule in many high- and most middle-income countries. Only with improved data access can some of the key analytical questions on the topic be addressed.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a large number of background references for the material presented and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [5], [6], [7].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Robert Holzmann