Elevator pitch

The Italian labor market suffered a sizable negative shock from the double-dip recession and has since experienced a moderate recovery beginning in 2014. Despite some improvement, unemployment remains higher than pre-crisis levels, especially for young workers. Female participation has been slowly increasing. Regional heterogeneity is still high, with the stagnating south unable to catch up with the north. Real earnings have been increasing, but productivity is stable at relatively low levels compared to other European countries. Finally, undeclared employment is high, especially in the south.

Key findings

Pros

After increasing significantly during the recent double-dip recession, both average and long-term unemployment began to decrease in 2014.

Job vacancies have increased since the large drop in 2009.

Female labor force participation is increasing, albeit slowly.

Older workers’ (aged 55–64) labor force participation has increased substantially in recent years.

Real earnings have increased, although they should be accompanied by proportional increases in productivity, which so far have not been seen.

Cons

Unemployment remains higher than pre-crisis levels.

Southern regions are lagging behind the rest of the country in all labor market aggregates, with no appreciable sign of convergence.

Female labor force participation is still low, especially in the south.

There has been a large increase in youth unemployment since the crisis, with only minor improvements seen since 2014.

The labor force participation of young individuals (aged 15–24) has decreased significantly since 2000.

Author's main message

Italy’s labor market performance is characterized by pronounced differences across age groups. Young individuals are facing high unemployment and low participation rates, while older individuals have seen their participation and employment levels increase. Regional differences are still significant, as shown by a more dynamic north and a stagnant south. Italy’s structural issues threaten to limit the extent of its ongoing moderate recovery. Among other measures, policymakers should promote youth employment activation policies and invest more in research and innovation programs across the country, as well as creating a more competitive business environment in the south by tackling inefficiencies and corruption and making private investments more profitable.

Motivation

The Italian economy, one of the largest in Europe, was severely hit by the recent double-dip recession, and full recovery has yet to happen. The current favorable economic scenario, characterized by steady economic growth in the whole euro area, represents an important opportunity to implement some needed structural reforms and tackle key labor market problems, such as high youth unemployment and the north–south disparity.

Discussion of pros and cons

Aggregate issues

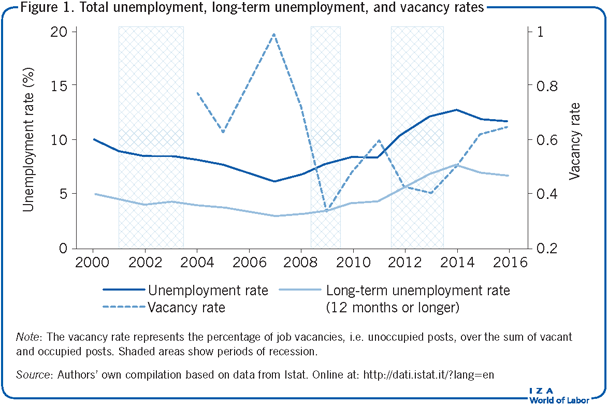

In the last 16 years, the Italian economy underwent three main recessions, which lasted, respectively, from February 2001 to July 2003, from March 2008 to May 2009, and from June 2011 to April 2013 [1]. Even though the economy had largely recovered from the 2001 downturn, the double-dip recession that followed from 2008 to 2013 constituted an additional sizable negative shock that strongly undermined Italy’s labor market performance, leading to alarmingly high levels of unemployment up until 2014.

Figure 1 displays the evolution of the unemployment rate, the long-term unemployment rate (defined here as unemployment lasting for more than 12 months), and the vacancy rate. The lowest level of unemployment was reached in 2007 at 6.1%, with long-term unemployment at less than 3%. Today’s unemployment is still very distant from pre-crisis levels. In 2016, the unemployment rate was still high at 11.7%, and the long-term unemployment rate was 6.7%. Both unemployment aggregates reached their peak in 2014 before starting to decline afterwards, albeit at a mild pace. As indicated by the substantial variation in the vacancy rate, the partial recovery around 2010 was arrested by a longer period of recession from 2011 to early 2013, which resulted in vacancies dropping to less than half of the 2007 levels. Even if the economy seems to be in an upward pattern since 2014, the vacancy rate is still lower than pre-crisis levels.

Labor force participation—Aggregate, gender, and age

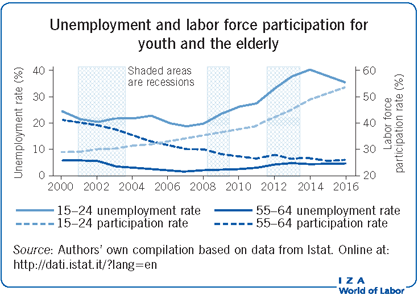

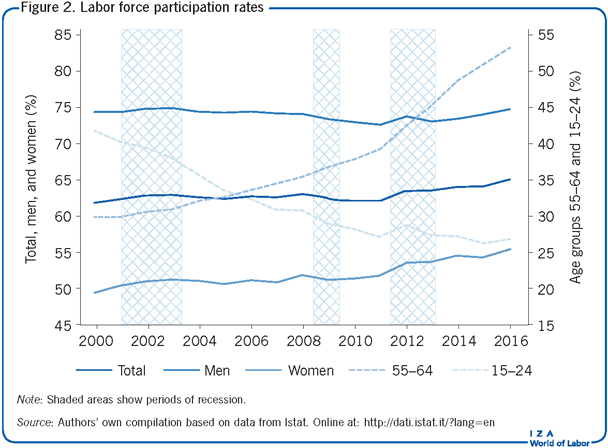

Total labor force participation has slightly increased since 2000, and most of the change is concentrated among older and young individuals. The participation rate among older individuals (aged 55–64) has accelerated since the early 2000s, resulting in an increase of about 25 percentage points between 2000 and 2016, now standing at 53.4%. This phenomenon should be interpreted in light of recent pension system reforms that increased the minimum retirement age, thus driving further participation among older individuals.

The higher participation of older workers is mirrored by an alarming decrease in young (aged 15–24) individuals’ participation, which is currently 15 percentage points lower than its 2000 value. Figure 2 shows that only around one-quarter of all individuals aged 15–24 are actively participating in the labor market. This low participation rate is not explained by an increase in full-time enrollment in education. Instead, it is due to the emergence of NEET youth (those not in education, employment, or training), a phenomenon that has recently gained policymakers’ attention. In 2008, the incidence of NEET youth was 17%, and by 2013 it had reached 22%. Today it is stable at around 20% [1]. An evaluation of the geographic dispersion of NEET youth reveals a worrying trend. The incidence of NEETs in Italy is around 14% in the north, 17% in the center, and almost 28% in the south [2].

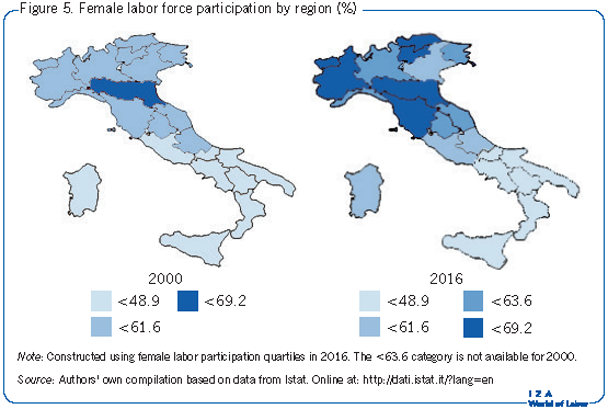

On a positive note, female labor force participation increased by around five percentage points from 2000 to 2016, though the current participation rate is still lower than those found in other EU countries. This pattern can be explained by various institutional features that characterize the Italian economy, including an insufficient provision of childcare and flexible contract arrangements, as well as deeper cultural factors. Male participation has remained practically stable, with a temporary, small decrease observed during the double-dip recession.

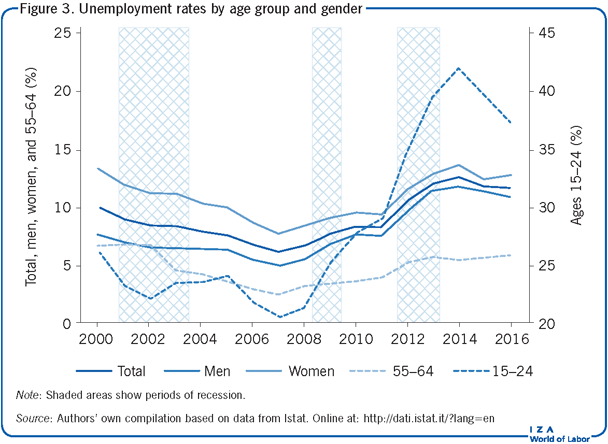

The demographics of unemployment—Age and gender

As already noted above, unemployment levels are still higher than pre-crisis levels. The 2011–2013 recession generated a peak in unemployment of around 13% in 2014. Still, the largest increase was in youth unemployment, which rose more than 20 percentage points from 2007 to 2014, reaching over 40% before finally starting to decrease (Figure 3). This pattern, together with the increasing labor inactivity of young individuals displayed in Figure 2, indicates that the youth have suffered the most from the effects of the Great Recession. While discouraged young individuals have been drawn out of the labor market in massive numbers, those still actively seeking employment face great difficulties in finding an occupation. By contrast, older individuals are characterized by a more stable unemployment rate, and they represent the only age group for which unemployment in 2016 is lower than the pre-crisis level.

Earnings

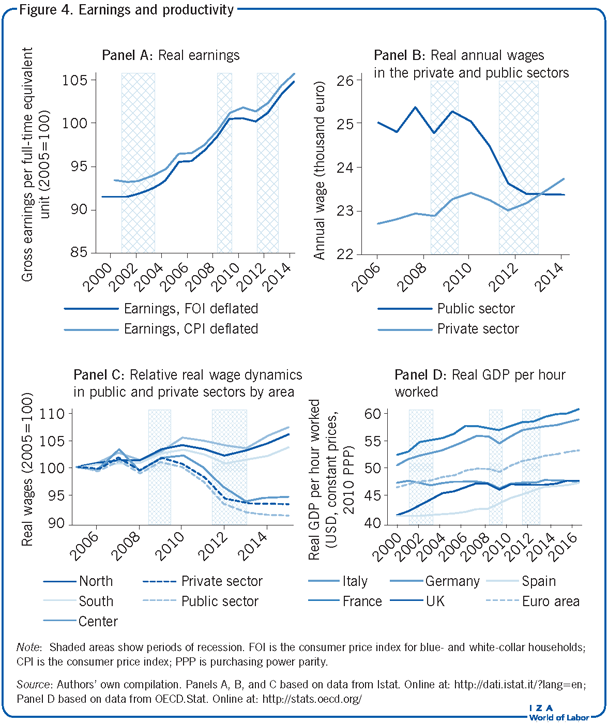

Panel A of Figure 4 displays the aggregate dynamics of employees’ average earnings in enterprises with more than ten employees. The figure exploits two different deflators: the famiglie di operai e impiegati (FOI, which is the consumer price index for blue- and white-collar households) and the indice prezzi consumo armonizzato (IPCA, which is a harmonized index of consumer prices). The former specifically refers to consumption of households whose reference person is an employee, while the latter is calculated according to EU regulations and is commonly used to compare inflation rates among EU member states [3]. As seen, the upward trend in earnings decelerated during the double-dip recession.

Panels B and C present a comparison between white-collar wages in the public and private sectors, as established by national collective agreements (contratti collettivi nazionali di lavoro); both are deflated using the FOI index. When examining panel B, the steady decrease of real public wages since the start of the recession is noticeable, which is mainly due to the public wage moderation policies implemented through missed inflation adjustments. Most of the post-crisis wage adjustments were achieved by a contraction in public wages, and, as a result, the gap between real public and private wages disappeared around 2014. Given the strong economic heterogeneity between Italian macro-regions, the same collectively bargained salary might have different purchasing power in the north, the center, and the south. Panel C displays the relative changes in public and private sector real wages in the three economic areas starting from a base value of 100 in 2005. This panel suggests that the south has experienced a more pronounced relative decrease in public sector real wages as well as a lower increase in private sector real wages due to different inflation dynamics.

Panel D displays a crude measure of labor productivity, expressed as real GDP per hour worked, for Italy and a number of EU countries as well as the euro area as a whole. Due to the stagnation of both GDP growth and of hours worked, real GDP per hour has been flat in Italy, with some small variability due to the recession. This stands in stark contrast with the rest of the euro area, which is characterized by a marked positive trend. The gap between Italy and Germany and France is widening, whereas Spain and the UK (whose series stopped growing after the recession) reached levels of real GDP per hour worked that are comparable to Italy in 2016. The factors behind this poor performance are various, including low investments in human and physical capital, insufficient resources devoted to research and development, the post-crisis credit crunch, an overall loss of confidence among consumers and firms, and the still widespread prevalence of inefficient institutions coupled with the slow pace of reforms.

Female labor force participation—Aggregate and by area

Geographic differences in female labor force participation have remained stable since 2000 (Figure 5). Considering the period 2000–2016, total average female labor force participation in Italy increased by about 12%. However, variation between regions is still large and there seems to be no clear convergence path, with southern regions still lagging far behind. While the increase in participation in some southern regions was above the median—for example, the increase in Calabria and Basilicata was around 13% and 15% respectively—the performance of other regions was poor: in particular, Campania and Sicily were the only two regions in Italy that experienced essentially no change in female labor force participation. Currently, Campania and Sicily are the two regions with the lowest rates of female participation, at around 37%. By contrast, some northern regions, such as Emilia-Romagna and Valle d’Aosta are characterized by a much higher participation, at 67.69% and 67.60% in 2016, respectively.

In general, the data on female labor force participation are encouraging. However, while aggregate participation ranges from 60% to 67% in northern regions, the south still lags far behind, with only 37% to 53% of women currently participating in the labor market. Given these differences, overall female participation is still unsatisfactory in the south, with large room for improvement; for example, through standard policies addressing the availability of childcare provision and more flexible work-time arrangements, as well as broader policies aimed at increasing female empowerment, given that gender inequality is traditionally more rooted in southern regions [4], [5].

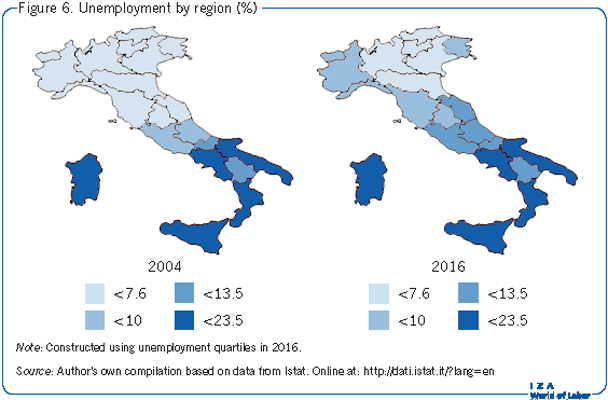

Unemployment by region

The differences between unemployment rates across regions did not change much, in relative terms, after the crisis (Figure 6). Southern regions have always been characterized by much higher levels of unemployment than the north, typically three to four times higher in pre-crisis years, while smaller differences existed between central and northern regions. At the end of 2007, the unemployment rate in the south was slightly more than three times higher than in the north, at 11.1% and 3.5% respectively. The double-dip recession slightly reduced this gap, starting a slow and ongoing convergence process; southern unemployment is currently about 2.5 times higher than in the north. Unfortunately this convergence seems to be a result of poor performance by northern regions rather than improvement by southern regions. The increase in unemployment in Italy in the period 2004–2016 was about 47% (i.e. from 8.1 to 11.9%). In southern regions (with the exception of Calabria and Abruzzo, where unemployment increased by 66.1% and 57.8% respectively) the unemployment rate increased by less than 32%. Three non-southern areas registered alarming increases in unemployment, more than doubling during 2004–2006: Marche (center), Valle d’Aosta (north), and Trento province (north). The changes in these regions were respectively from 5.4% to 10.8%, from 3.2% to 6.9%, and from 3% to 8.8%.

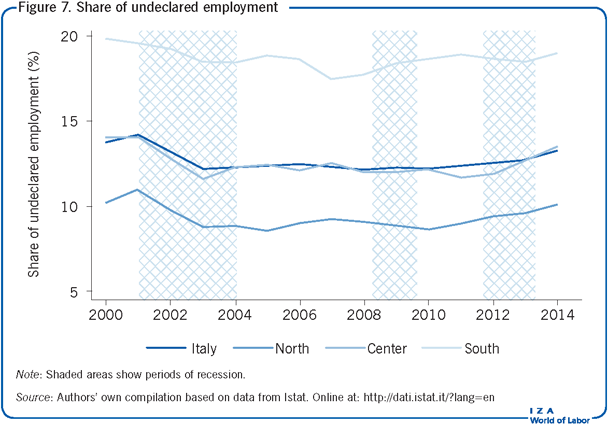

Undeclared employment

Official statistics should be able to detect all employed people, even if they are employed in the shadow economy. Even so, the phenomenon of undeclared work is especially important in Italy, where a sizable share of production is concentrated in the shadow economy. This leads to far reaching negative consequences in terms of efficiency, labor standards, and fiscal revenue. The need to reduce undeclared work is crucial, especially in the south. According to the Italian National Institute for Statistics (Istat), in 2014 around 13.3% of all Italian workers were not covered by a regular contract, hence falling into the shadow economy, and the rate was quite varied across regions. As shown in Figure 7, almost one-fifth of southern employment is not declared, while the share is only 10% in the north. This regional difference has not decreased over time.

Limitations and gaps

Limitations in the available data have forced the current analysis to neglect an important aspect of the Italian economy: entrepreneurs and small enterprises, especially with respect to earnings. The available data on real earnings in the private sector were restricted to employees in firms with more than ten employees, thereby excluding entrepreneurs and self-employed individuals. In addition, Labor Force Survey data do not provide reliable information on individuals’ earnings before 2009. In the absence of administrative tax returns data, this prevents an evaluation of the evolution of the income distribution as well as any reliable analysis of inequality.

The analysis of wages in the private and public sectors was based on the amounts stated by national collective bargaining agreements. While all workers in the public sector are covered by such agreements, this approach might leave out a substantial fraction of private sector workers, since, for example, nearly 24% of workers in that sector were self-employed in the last quarter of 2016 [6].

Further limitations include the unavailability of regional unemployment data before 2004, of hire rate statistics, and scarce availability of immigrants’ labor market aggregates.

Summary and policy advice

The Italian labor market is undergoing a moderate recovery that could be aided by policy interventions aimed at increasing efficiency and competitiveness. A major issue that should be of paramount importance to policymakers is the strikingly poor performance of Italy’s southern regions. This well-known long-term stagnancy pattern, exacerbated by ineffective institutions and policies, places a heavy burden on Italy’s recovery. Innovative structural policies aimed at creating a more competitive business environment in the south and making private investments more profitable are required. Legality should be restored by sharply reducing the extent of the shadow economy, which would result in increased fiscal revenues and more efficient allocation of resources.

Another major problem is the stunningly poor labor market performance of young Italians, whose participation has declined markedly since the turn of the century, owing to increased difficulty finding a job. Such poor performance stands in contrast to the relatively good performance of older individuals, suggesting once again that the Italian economy is not investing enough in its younger citizens. Average productivity should also be increased in order to keep up with the rest of Europe, by promoting investments in human and physical capital and allocating more resources to research and development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Francesca Marino and Luca Nunziata