Elevator pitch

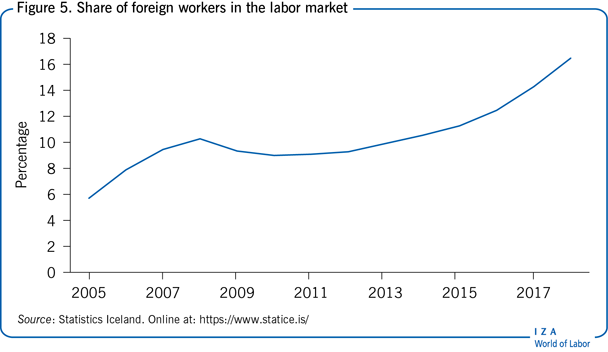

The Icelandic labor market is characterized by high union density and the Icelanders’ willingness to work, as labor force participation is high, the work week long, and people retire late. The resilience and flexibility of the Icelandic labor market was put to the test in the Great Recession as a large share of employees in the labor market experienced a fall in work hours and a fall in nominal wages, while unemployment rose less than expected. In recent years there has been a strong influx of foreign workers, mostly from Eastern Europe. Studies have shown that their labor force participation is no lower than that of Icelanders.

Key findings

Pros

The labor market is functioning well with a high level of employment and low levels of unemployment, with active participation of immigrants.

The labor market recovered quickly following the Great Recession; wage levels have recovered and unemployment is almost down to pre-recession levels.

Long-term unemployment and youth unemployment are down to pre-recession levels, indicating limited long-term effects of the recession.

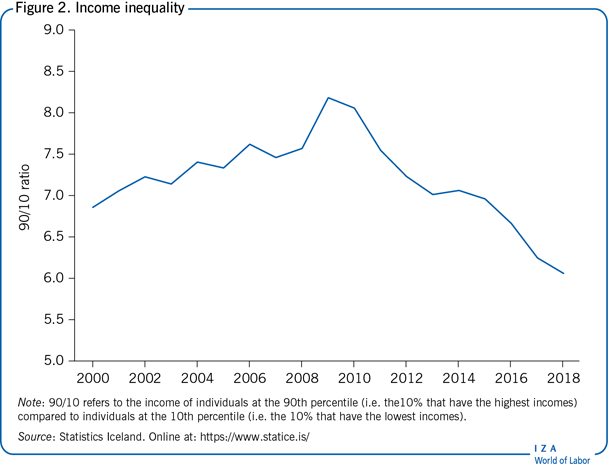

Income inequality was growing prior to the crisis, but fell during it, leaving Iceland with the lowest Gini coefficient among OECD countries.

Cons

There is an increased risk of education mismatch as a growing share of the population attends tertiary education, disproportionally women, while job creation has in recent years largely been in the blue-collar service sector.

Robust economic growth led to a shortage of labor which was supplemented through immigration, often using temporary work agencies, which brought an increased risk of social dumping.

Real wage growth in recent years has been in excess of growth in productivity, leading to inflationary pressures and a deterioration of Iceland’s competitive position.

Author's main message

The Icelandic labor market is flexible and adjusts quickly to adverse circumstances as evidenced in the Great Recession, where wages and work hours adjusted with a substantial increase in unemployment. With the recent exponential growth in tourism leading to strong economic growth, real wage increases bargained for in the labor market have been greater than the increase in productivity, leading to a loss in the competitive position of the country. Immigrants make up a growing share of the labor market, which poses new challenges now that economic growth has again slowed.

Motivation

The Icelandic labor market has been shown to be flexible, where unemployment remains low throughout the business cycle, while real wages tend to fluctuate even more than economic growth [1]. From the year 2000, Iceland's labor market has gone from a period of strong growth, through a sudden and deep recession, to a period of renewed growth. During this time, the flexibility of the labor market has been put to the test, especially during the Great Recession. While the effects of the recession were certainly felt in increased unemployment, the falling demand for labor was also met by a fall in work hours, a cut in nominal wages, and net emigration. As economic growth picked up again, so did employment, and by 2016 the unemployment rate was almost down to pre-recession levels.

In general, the Icelandic labor market can be characterized by high union density as well as the general willingness to work, which can be seen in high labor force participation rates among both men and women, long work hours, and late retirement [2].

Discussion of pros and cons

The Icelandic economy is small with undiversified production, which is mostly related to natural resources, and has historically experienced large fluctuations in economic growth. This has led to fluctuations in unemployment, as well as in weekly work hours, but most importantly to large swings in real wages, swings that are even bigger than those of economic growth. Since the turn of the century, the composition of the labor force has changed significantly, with a growing share of foreign workers. There have also been structural changes in the economy. Until 2007, the fastest growing sectors in terms of employment were construction and finance. After economic growth picked up again following a deep recession, there has been renewed growth in construction, but to an even larger extent, growth in tourism services.

A secure and flexible labor market

The legal framework for the Icelandic labor market is quite lax, with the protection of employees mainly stipulated through collective bargaining agreements. There are, therefore, no laws on minimum wages. Instead, each collective bargaining agreement stipulates the minimum wages under that contract, and for the industry in which it operates. Furthermore, rules for hiring and firing are lenient. Collective bargaining contracts generally stipulate a period of three months’ notice on both sides, while firing is generally done without awarding severance pay [2].

There is mandatory membership in pension funds. The pension system is fully funded and dates back to 1970. Both the employer and the employee are required to contribute a share of the employee's wages. There used to be separate systems for the public and private sectors, but in 2017 the rules and regulations regarding the two systems were unified. At the same time the employer contribution in the private sector was raised to ensure that the contributions would cover adequate pension payments at the time of retirement.

Iceland has a system of socialized health care, where unemployed people are eligible for unemployment insurance, and where parents receive paid leave on the birth of a child and also receive child benefits from the government through the tax system.

Social partners work together in times of trouble

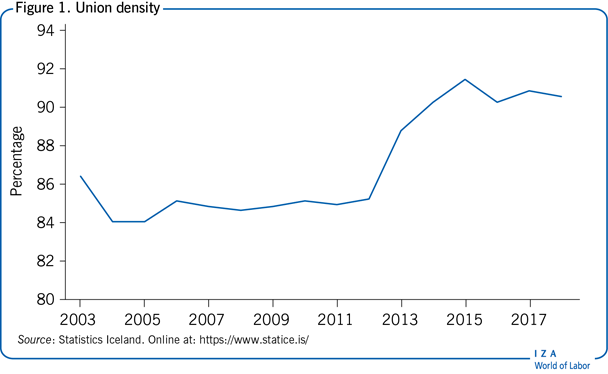

The Icelandic labor market model has many similarities with the labor market arrangements in the other Nordic countries. Trade union density is high in Iceland and, unlike most other countries, has not fallen in recent years. In 2019, union density measured 90% (Figure 1), and there are 172 unions, most of which belong to one of four major union federations.

Collective bargaining agreements in Iceland have status equal to law. That includes that the minimum wage determined in each contract is the minimum wage for that industry. Many contracts, especially for unskilled workers, have a priority clause, which stipulates that employers are not allowed to hire anyone who is not a union member. This effectively means that each employee automatically becomes a member of the union and has all the same rights as a union member [1].

In times of economic growth, when expectations are optimistic, unions often decide to negotiate on their own behalf, with the expectation of higher wage settlements. However, in times of slow economic growth and increased unemployment, unions sometimes prefer to delegate negotiation to the federation to which they belong, in order to ensure that, of the possible wage increases, every member gets the same increase, or at least that purchasing power is preserved. Agreements are usually synchronized in the way they cover the same period and expire at the same time. In recent decades the government has usually stepped in to facilitate the signing of new agreements, with promises of changes to the tax system or to the social security system [2].

A few months after being hit by the Great Recession in 2008, the sitting government left power in the wake of massive protests, and a coalition of two left-leaning political parties took office. The new government defined itself as a Nordic Welfare Government that aimed to shelter the lowest income groups from the effects of the crisis. One of the actions of this government was the so-called Stability Pact it reached with the social partners (union federations, employer associations, central and local governments). As part of the Stability Pact, wage increases in collective bargaining agreements were postponed, and the expiration dates of agreements were extended [3].

By the time economic growth picked up after the recession in 2010, the wage increases in collective bargaining agreements had more than made up for the nominal wage cuts during the recession. When new centralized collective bargaining agreements were signed in the spring of 2019 unions faced slowing economic growth. In light of the slowing growth in the wake of the bankruptcy of Iceland's second largest airline, the objective of increasing the wages of those at the bottom end of the wage distribution relative to other wages was viewed as even more important than in earlier agreements (Figure 2). The collective bargaining agreements cover the years 2019 to 2022, which is unusually long for agreements in Iceland.

The current collective bargaining agreements include a number of commitments by the central government to facilitate signing, such as tax reductions, more generous family benefits and longer parental leave, and support for affordable housing. A novelty in the agreements is a link between wage increases and growth (GDP per capita). If GDP rises more than projected in the wage settlements, wages will increase more than stipulated in the agreements.

With the high level of union density, wage dispersion is relatively low. During the crisis the emphasis was on lowering the nominal wages of the higher paid, while preserving the status of the lowest paid, leading to a fall in wage dispersion in recent years. This policy and emphasis in the collective bargaining agreements has also led to the share of working poor being the lowest among the OECD countries, as is the Iceland's Gini coefficient, while average income per capita is one of the highest.

Working long and working late

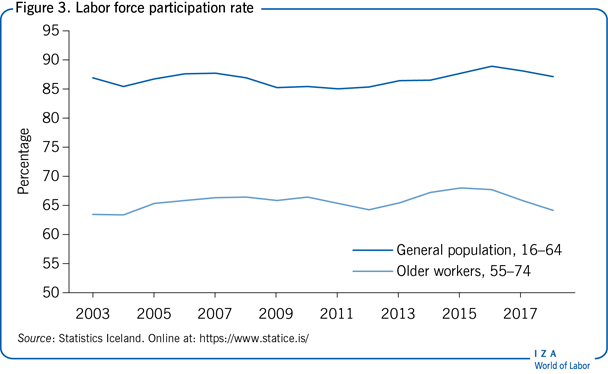

Icelanders’ willingness to work is manifested in the country's high labor force participation rate (Figure 3)—among the highest of the OECD countries, for both men and women. In 2018, it measured 87%, with men's labor force participation rate at 90% compared to women's at 85%. In the recession that hit in 2008, the labor force participation rate fell by 4 percentage points for men, but by only 1 percentage point for women.

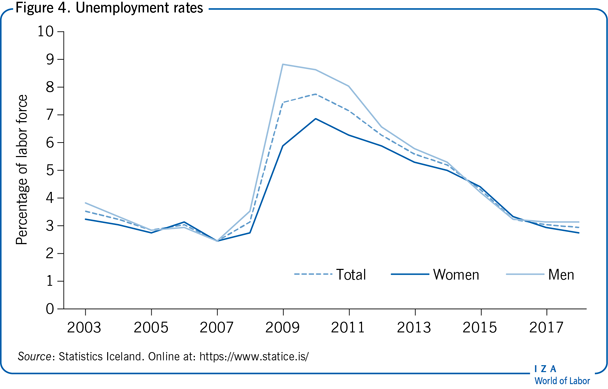

The unemployment rate reached a low of 2% in 2007, before the recession hit; it was the same for men and women (Figure 4). When the recession happened, unemployment rose sharply and reached a high of 8% in 2012. While increasing almost four-fold, the unemployment rate never rose as much as initially feared. It rose faster for men than for women at the beginning as many sectors dominated by men—construction and banking—were severely affected. The unemployment rate for women peaked later mainly due to cuts in the public sector. Since then unemployment has fallen to just below 3%, and it is again similar for men and women.

The working week in Iceland is on average 40 hours, with men working an average of 43 hours and women 36. The average working week for women has not changed much over the last 20 years, while men's average weekly work hours have fallen from 48 hours to 43 hours since the 2008 crisis.

Not only do most Icelanders work long hours, they also retire late. The normal retirement age is 67 years for both men and women, the highest among the OECD countries. Men generally retire a year later, at 68 years of age, while women have tended to retire a little earlier, on average at the age of 66. The labor force participation rates of people aged 55–74 is high in Iceland, over 65%, on average (Figure 3): almost 60% among women and over 70% among men.

One of the characteristics of Iceland's flexible labor market is the large fluctuations in real wages, which often exceed fluctuations in economic growth. In the years leading up to the Great Recession, real wage growth was, in general, above the average growth in productivity. The wage increases stipulated in the collective bargaining agreements were generous, demand for labor was high, and the inflation rate was subdued as the local currency strengthened. However, in the autumn of 2008, when hit by the recession, this picture changed almost overnight. Real wages fell by over 10% over three years, while GDP contracted by 8%. The economy started growing again in 2010 and almost immediately real wages started growing again, reaching pre-recession levels already by 2014.

Men and women—Not quite equal

Iceland is known for gender equality and has ranked number one on the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Index for 11 consecutive years (2009–2019). The country has at times been groundbreaking when it comes to the advancement of women. In 1980, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir was elected as the nation's president, the first woman in the world to be democratically elected to the role.

In recent years several major steps have been taken toward gender equality in the labor market and the corporate world. In 2000, a new law on parental leave came into effect, giving parents nine months of leave on the birth of a child. Mothers have a right to three months’ leave and fathers to another three months’ leave. They can then choose how three additional months are divided between them. In 2020 the total leave time was extended to 12 months.

In order to increase the share of women in the corporate world, in 2013 Iceland introduced a gender quota law. The law requires that the boards of companies with more than 50 employees consist of at least 40% of each gender. The Icelandic gender quota law applies to both public and private limited companies, as well as to pension funds.

While for decades Iceland has had laws requiring equal wages for both men and women, there is still a significant gender wage gap, and the unadjusted gender wage gap is slightly higher than in other Nordic countries. While falling from 2000 to 2008, the unadjusted gender wage gap remained relatively unchanged from 2009 to 2016. As a response to the persistent wage gap, the social partners developed and agreed on a Gender Pay Standard. While the pay standard does not guarantee equal wages, it should ensure that the evaluation of jobs and determination of wages do not depend on gender. Starting in 2018, all organizations with more than 25 employees will have to fulfill the requirements of the Gender Pay Standard [4].

Structural changes: Immigration and education

Immigration

The biggest change in the Icelandic labor market in the last couple of decades has been the growing share of foreign workers (Figure 5). In the early 2000s, the Icelandic economy was growing fast, and an excess demand for labor led to a rapid influx of foreign workers. When the financial crisis hit in 2008, many of those workers left the country, contributing to the lower than expected rise in unemployment.

When the economy started growing again, especially due to the growth in tourism, which led to renewed excess demand for labor, it did not take long for foreign workers to start immigrating again. In recent years net immigration has been even stronger than in the years before 2008. It is now estimated that foreign workers make up around 16% of the Icelandic labor market.

Starting in 2004, the government enacted several laws which ensure that the rights of foreign workers are the same as those of native workers. All foreign workers, including those working for temporary employment agencies, are entitled to the same rights and minimum wages as others working in Iceland. A recent report published by ASÍ, the largest confederation of unions, shows that some employers do not comply with these laws and seem to take advantage of their foreign employees, who are not always aware of their rights [5].

Education

As in most industrial countries, a majority of those enrolled at university in Iceland are women. The difference in enrollment between men and women is quite large, with 39% of men aged 25–34 having finished tertiary education, compared to 56% of women. Still, however, men comprise the majority of students in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects. In the current period of economic growth, most job creation has been in tourism services and construction, neither of which offer many jobs requiring tertiary education. At the same time, the share of university-educated people is rising among the unemployed.

Limitations and gaps

Iceland has been able to navigate the ebb and flow of recent business cycles remarkably well, as most economic indicators are as favorable as, or even more so than, before the Great Recession. Still, Icelandic society might face some new challenges with the immigration of foreign nationals if economic growth slows down markedly or stagnates. At the same time, real wages are increasing in excess of productivity, reducing the competitiveness of the Icelandic economy.

In order to inform future policy, data gathering methods must improve. There are gaps in the wage data, with growing sectors missing or underrepresented. Immigrants are also underrepresented in survey data, as they may not be registered or not willing or able to respond to surveys.

Summary and policy advice

The Icelandic experience shows that with a flexible labor market and social partners’ cooperation it is possible to overcome even the deepest of recessions. The policy put in place by both the social partners and the government during the recession was quite successful and managed to shelter the lowest paid and reduce further the already low wage inequality. With Iceland heading into a period of slower growth and increased unemployment, the flexibility of the Icelandic labor market will again be put to the test. With the large and growing share of immigrants moving to and settling in Iceland the challenge is to integrate foreign workers into the labor market. Many come from lower-income countries and are perhaps willing to work at lower wages than the minimum mandated by collective agreements, increasing the risk of social dumping.

Another challenge is to reduce the mismatch between education and job creation that can arise with a larger share of the population receiving tertiary education while many new jobs do not require higher education. Furthermore, the outlook is for increased demand for people with STEM education while the share of STEM-educated among university graduates, especially women, is quite low.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Katrín Ólafsdóttir