Elevator pitch

One of the primary considerations in policy debates related to energy development is the projected effect of resource extraction on local workers. These debates have become more common in recent years because technological progress has enabled the extraction of unconventional energy sources, such as shale gas and oil, spurring rapid development in many areas. It is thus crucial to discuss the empirical evidence on the effect of “energy booms” on local workers, considering both the potential short- and long-term impacts, and the implications of this evidence for public policy.

Key findings

Pros

Employment increases during energy booms.

Local incomes and wage rates increase during energy booms.

Compensation-related benefits are widespread and occur across many industries, types of occupations, and segments of the wage rate distribution.

US experience suggests energy booms may lead to positive spillovers to other sectors.

Cons

Energy booms are associated with reduced educational attainment and student achievement in local areas.

In some cases, experiencing an energy boom may have negative effects on an individual's long-term income.

Volatility from energy booms may complicate spending and savings decisions, thereby affecting retirement choices and other life cycle outcomes.

Most research has focused on how energy booms affect individuals through monetary channels, but other dimensions are also important.

The literature disproportionately comprises studies from the US.

Author's main message

Energy booms create a broad set of benefits that accrue to local workers in the short term. In policy debates related to placing restrictions or bans on energy development, these benefits will have to be considered relative to other factors, such as environmental degradation. When local economies go through an energy boom, public policies may help smooth out the boom-and-bust cycle and offer an avenue for more sustained improvement in labor market conditions. For example, policymakers should consider using severance tax revenue to fund permanent trusts that can help promote economic growth after the boom.

Motivation

Localized economic shocks that promote direct growth in a single sector can pose challenges to communities and policymakers. On the one hand, shocks can provide a source of income and employment for residents. On the other hand, shocks may be associated with negative externalities—such as elevated pollution levels and increased depreciation of local infrastructure—and new uncertainties related to the expected costs and benefits of the shock, how long the shock will persist, and how the effects of the shock will be distributed among the local population.

This article examines a particularly controversial local economic shock: an energy boom. An energy boom constitutes a rapid increase in energy exploration and production. Energy booms, and other types of resource booms, can be a particularly difficult type of economic shock for communities to manage because they are often short-lived and followed by “bust” periods, which can impose transitional hardships on local residents. Energy booms also frequently create significant environmental degradation. Due to the challenges associated with energy booms, some communities have limited or banned energy development in resource-rich areas. For example, a variety of jurisdictions around the world have either limited or banned energy production through hydraulic fracturing or “fracking,” including France and New York state. Other jurisdictions have, at least relatively speaking, embraced fracking and its potential economic benefits.

Like many areas of policy, a central feature of the debate related to energy development is its effect on workers. Potential benefits to local workers are often referenced as a reason for pursuing energy development because the labor market provides a common avenue by which most residents can gain from the boom. Given the policy relevance of the labor market, researchers have increasingly sought to evaluate the effect of energy booms on local economies.

Discussion of pros and cons

Background on energy booms

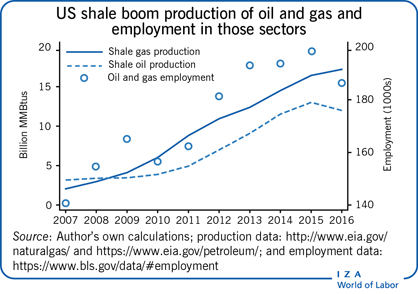

Energy booms can be caused by resource discoveries, price changes (typically large price increases), and technological improvements that reduce the costs of extraction. The discovery of extremely large petroleum reserves in Texas during the early 1900s provides an example of a discovery-based energy boom, as does the discovery of North Sea oil fields near Norway in the 1960s. The 1970s oil embargo by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), which led to a spike in oil prices and dramatic increases in drilling and production from other regions of the world, is an example of a price-based boom. The most recent major energy boom, involving the extraction of both petroleum and natural gas, has been driven by technological advancements. Improvements in horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and other aspects of extraction suddenly enabled oil and gas deposits in shale plays to be profitably extracted during the mid-2000s. While the fracking boom has predominantly affected North America, the presence of large shale deposits in other regions of the world suggests that the boom may eventually have global effects.

Energy booms have occurred across different eras and geographic regions. While this article focuses primarily on booms that occurred in the US, because this is where most of the recent literature has focused, other examples of energy booms can be found in the suggested “Further reading.”

Research design and context

The effects of energy development have been evaluated empirically using several different methods. In early empirical work, country-level regression models from a single point in time were sometimes used to evaluate the relationship between economic growth and resource production. However, while these models were helpful for establishing some provocative correlations that spurred future research, they were challenging to use for causal inference due to the difficulty of avoiding omitted variable bias in a cross-sectional empirical setting.

More recently, researchers have leveraged “natural experiments” to estimate the effect of energy booms on local communities. Natural experiments involve using a “treatment” and “control” group to estimate the effect of energy booms. Treatment groups are areas with high levels of energy production and control groups are areas without significant energy production. These two groups are then compared over time. Changes that occur at the time of the energy boom, relative to pre-boom differences, provide estimates of the effect of energy booms. While the regions falling in the treatment and control groups are not randomly assigned, comparing the two groups can lead to estimates of causal effects if the control group would have experienced similar changes over time as the treatment group had the boom not occurred. Researchers typically attempt to provide evidence in support of this assumption by identifying treatment and control groups that experienced similar temporal trends leading into the boom period. Most of the research described in the next section is based on work that employs an empirical framework based on a natural experiment.

In the context of energy booms, results from natural experiments are useful for capturing local effects that occur through channels closely related to extraction (e.g. increased demand for local labor, royalty payments to local landowners). Energy booms may also have effects outside of local areas. For example, they may reduce energy prices over large geographic zones. While both local and non-local effects are relevant, local effects can be especially important because local policymakers (e.g. county commissioners) often craft policies that either support or restrict extraction based on expectations regarding the effects of extraction on the local community.

Short-term benefits of energy booms on local workers

Energy booms increase overall demand for local labor, where “local” has often been empirically defined as those living in a county that is undergoing a resource boom. For example, the peak of the 1970s oil boom in the US was associated with a 20% increase in employment in booming counties [1]. National studies of the most recent US energy boom suggest that it led to 220,000 additional jobs in booming counties [2] and 640,000 additional jobs when considering spillover effects to neighboring counties (i.e. within 100 miles) [3]. Moreover, these employment increases were not confined to the mining and extraction sector. The 1970s US oil boom increased local employment in the construction, retail, service, and transportation sectors [1], and the more recent boom led to increased employment in the accommodation, construction, retail, and transportation sectors [2].

Increased demand for labor benefits local workers through several channels. First, it reduces unemployment. Estimates indicate that the recent US energy boom decreased the unemployment rate by 0.43 percentage points during the Great Recession [3]. Second, increased demand for labor can increase wage rates. A study of the recent energy boom finds that it increased mean wage rates in non-metropolitan booming areas by 7%, on average, between 2006 and 2014 [4]. The increase in wage rates occurred across the distribution of wage rates. In particular, the estimated increase in wage rates at the lowest decile, first quartile, median, third quartile, and top decile of the distribution were seven, ten, nine, six, and five percentage points, respectively. A third channel through which energy booms may benefit local workers is by enabling them to work more hours, thereby bolstering earnings, but this channel has received less attention in the literature. Ultimately, through a combination of these and other channels, local incomes substantially increase during energy booms [1], [2], [3], [4].

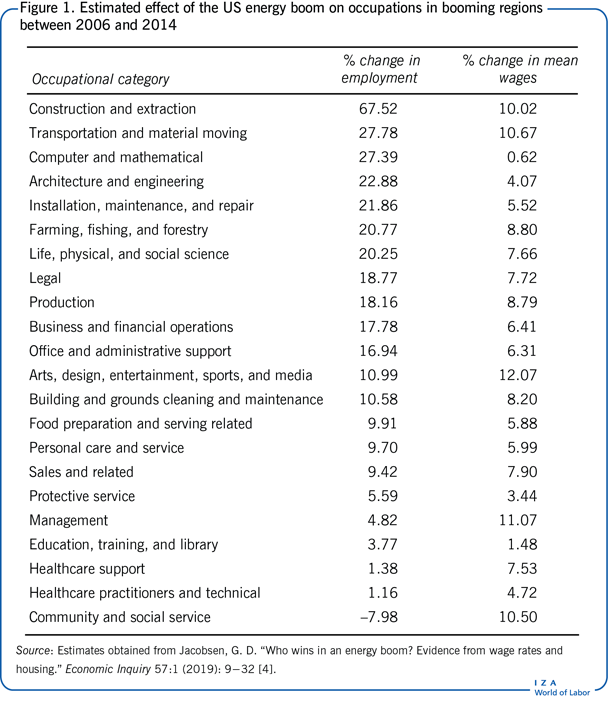

Importantly, the increases in wage rates and incomes described above are not driven by a small set of jobs closely connected to the boom sector. Figure 1 shows the estimated effect of the recent US energy boom on employment and mean wage rates in different occupations between 2006 and 2014 [4]. Almost every occupational category experienced an estimated increase in wage rates. This increase was experienced regardless of whether the occupational category experienced a contemporaneous increase in employment. The implication of this finding is that booms create a tighter local labor market that increases earnings for a wide variety of workers.

Booms and education

While booms create new opportunities for local workers, pursuing these opportunities may come at the expense of pursuing other opportunities related to career development. Perhaps most importantly, the higher wages paid during booming economies may pull workers into the labor force that would have otherwise furthered their education. After the boom ends, it is possible that workers who forewent education will be less equipped for the workplace than they otherwise would have been.

Recent studies have confirmed that energy booms lead to reduced educational attainment. For example, during the 1970s, a coal boom in the Appalachian region in the US led to decreased high school enrollment rates in Kentucky and Pennsylvania [5]. Likewise, the recent fracking boom has also led to a decrease in educational attainment in booming areas in the US [6]. High school dropouts due to energy booms are more likely to be male than female, thereby contributing to the gender gap in high school dropout rates [6].

Booms can impair education by affecting school quality as well. In a study of the recent US energy boom that focuses on Texas, researchers find that energy development is associated with decreased student achievement in the form of lower pass rates on state exams [7]. The primary mechanism contributing to reduced achievement is that some teachers are drawn into new occupations because of the boom. As a result, teacher turnover and inexperience increase.

Long-term consequences of energy booms and busts

To fully evaluate whether the labor market effects of energy booms are beneficial to local workers, it is necessary to examine the effects of the boom in both the short term and the long term. There is not a clear theoretical prediction with respect to the long-term effects of a boom. Wealth that is accumulated in the short term due to the early benefits of the boom could help workers in the long term by providing them with the ability to afford more education; the ability to pursue riskier, higher-return jobs; or to cover the costs of moving to areas with greater opportunities. In contrast, if workers acquire boom-specific skills, then they may not be equipped to succeed in post-bust economies. This may result in them facing greater unemployment rates or being forced to take lower paying jobs than they otherwise would have obtained. The long-term effect of booms on local economies will also affect local workers. If booms provide a foundation for long-term growth through agglomeration spillovers, then workers will be more likely to benefit in the long term. On the other hand, if booms create growth in the extractive sector that crowds out growth in sectors with more promising long-term potential, then workers may be harmed in the long term.

Relative to the amount of research on the short-term effects of energy booms, the literature on long-term effects is much smaller, partly because the recent fracking boom is not yet mature enough to evaluate its long-term effects. One long-term study focuses on how county-level oil endowments in the southern region of the US stimulated county-level development from 1890 to 1990 [8]. The study finds that oil-abundant counties that specialized in energy production in the early part of the 1900s experienced increases in employment and per capita incomes that persisted throughout the remainder of the century. Potential channels for these positive effects are various types of agglomeration effects, such as better worker-firm matching in local labor markets and more learning and information-sharing across firms.

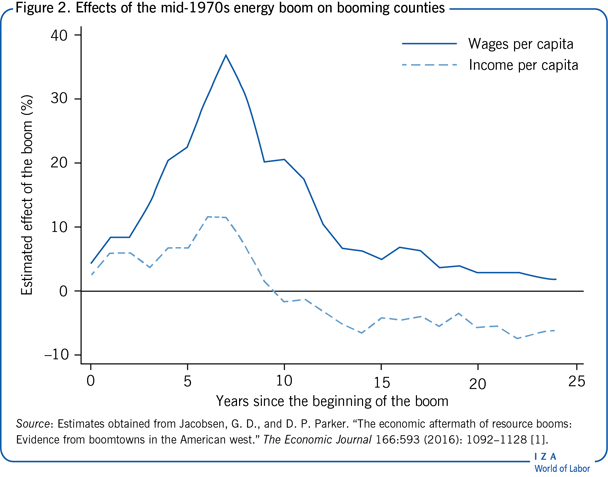

Another longer-term study examines the effects of the 1970s oil boom in the Rocky Mountain region of the US through the 1990s [1]. As shown in Figure 2, the study finds that wages per capita and income per capita both experienced strong increases during the boom. After the boom ended, wages and income began to decline relative to their peak levels. Ultimately, the effect of the boom in the post-bust period was estimated to be negative for income per capita and statistically insignificant for wages per capita. A decline in small business profits contributed to the negative income effects following the bust. The implication of the study for workers whose income predominantly comprises wages is that the effects of the boom in the long term are minimal. Reflecting this, the study estimates that the aggregate effect of the boom on income per capita in the booming region over the sample period was positive, equaling about $3,000.

The two studies described above differ in their implications with respect to the long-term effects of a boom. One study appears to paint a positive picture, while the other is neutral or negative, depending on whether wages or incomes are the outcome of interest. A potential explanation for the differing findings is that the studies focus on different regions. The study finding positive effects focuses on energy-abundant regions that tend to be located in urban areas or reasonably close to them [8]. In contrast, the study finding neutral or negative long-term effects evaluates booms in more remote rural communities [1]. While speculative, the different study settings suggest that energy booms that predominantly impact workers living near cities may have more beneficial long-term effects than those that predominantly effect remote areas.

A common feature of most existing work on energy booms, including both of the longer-term studies described above, is that the studies tend to evaluate the effect of energy booms on places, as opposed to people. Due to workers migrating to take advantage of boomtown opportunities, estimates based on aggregated place-level data may not capture the effects of booms on pre-existing residents. Recent work fills this gap by using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to evaluate the person-level effects of the 1970s US energy boom [9]. A key finding is that energy booms appear to lead individuals to delay retirement, potentially because households overspend during boom years or because energy busts depress property values. Delayed retirement represents a potentially hidden cost to workers and may be indicative of other hardships workers face when managing the dramatic economic swings associated with the boom-and-bust cycle.

Limitations and gaps

A key limitation in the existing literature is that increases in wages and incomes are not typically adjusted for inflation that is specific to the booming area. The rapid increase in economic activity during energy booms, combined with limited supply-side adjustment—whether due to the rapid onset of booms or concerns about the extent of their duration—can lead to substantial price increases. For example, one study estimates that rental prices in booming regions of the US increased by 5% due to the recent boom [4]. Prices likely increased for other goods as well. Adjusting the compensation-related effects of booms for localized price inflation would provide a clearer picture of the effects of energy booms on local workers.

Limited evidence on the long-term effect of energy booms on local workers is another shortcoming in the literature. As mentioned earlier, there are only a handful of studies in this area. Additional careful evaluations of the effects of energy booms over an individual's career would provide a clearer depiction of the complete effect of energy booms on local workers. Researchers in a variety of fields are increasingly using rich, administrative data sets to answer questions related to the environment and the economy that were previously difficult to address, such as the effect of air pollution on household earnings. Exploiting such data sets would likely prove valuable for the energy boom literature as well.

Another limitation of the literature is that, while it does shed light on worker compensation, it does not carefully evaluate worker well-being. Boomtowns are often associated with a variety of characteristics that are considered undesirable, such as depreciating infrastructure, housing shortages, elevated crime rates [10], diminished health (and corresponding decreases in productivity), and increased pollution levels. Busts and post-bust periods are sometimes associated with joblessness, abandoned properties, and a culture of despair. While it would be empirically challenging, assessing the effect of energy booms on these “softer” outcomes would enrich understanding of how energy booms impact the well-being of their workers. At a minimum, policy debates should consider the unquantified effects of energy booms on these factors along with the more traditional estimates on wages and incomes.

A final gap in the literature is that it has not comprehensively investigated the potentially heterogeneous effects of energy booms. The literature has predominantly focused on identifying average effects across broad regions. Local factors, such as regional industrial composition, existing infrastructure, proximity to major urban areas, environmental amenities, the housing stock, and education levels may influence the short- and long-term effect of an energy boom on local communities and their workers. Energy booms triggered by different factors, whether prices, discoveries, or technological improvements, may have different short- and long-term impacts. Additionally, energy booms may have different effects in different regions of the world and therefore the effects documented in the US-centric literature may not be representative of effects internationally.

Summary and policy advice

The literature on energy booms has generally documented substantial short-term benefits to local workers in the form of increased employment, wages, and incomes. These benefits accrue across industries, occupations, and segments of the wage rate distribution, suggesting that most workers are able to benefit from the effects of booms on local labor markets. The literature is limited in the extent to which it evaluates long-term effects for workers, but the available evidence suggests long-term effects are generally neutral or negative. To the extent they are negative, workers are compensated for small long-term negative effects by the large positive effects that occur during the peak boom years.

One of the policy implications of the above findings is that bans or limitations on energy development may lead to negative monetary effects for local workers, especially in the short term. In policy debates at the local level, monetary benefits to residents in the form of elevated compensation to workers, royalty payments to landowners, and increased profits to local businesses will have to be compared to potential costs, such as environmental degradation and depreciation of public infrastructure, as well as some of the more difficult to quantify outcomes described in the previous section, such as crime rates.

Another issue deserving attention from policymakers is that, while energy booms have had substantial short-term benefits on local labor markets, they have not had an obvious impact on long-term economic prosperity. The fleeting nature of the boom and the overall volatility of the boom-and-bust cycle may reduce its benefits, particularly if it creates challenges for individuals making financial decisions related to investments, spending, and consumption. Policymakers should thus consider enacting policies that increase the probability of boom-related long-term benefits and reduce the overall volatility of the boom-and-bust cycle.

One option for ameliorating the boom-and-bust cycle's volatile effects is to use revenue from severance taxes to create permanent trust funds. Severance taxes are paid based on natural resource extraction. Trust funds built on severance taxes could be managed such that fund withdrawals would at least partially offset the decreased economic growth caused by the inevitable post-boom energy sector contractions. Revenue from these funds could be spent on infrastructure that might bolster long-term growth, such as municipality services, parks, and schools, as well as subsidies for new businesses not dependent on the energy sector. Trust funds have been used to smooth out the economic impacts associated with energy development by a variety of governments, including Alaska, Texas, and North Dakota in the US, Norway, and Kuwait. Political tampering has at times interfered with the effectiveness of these funds. To optimize their impact, funds should be set up with clearly defined rules and should allow disbursements to be structured around economic downturns and strategic opportunities.

A final policy issue to consider is that, while this article has focused on the local effects of energy booms, the energy sector has global implications. Most notably, the energy sector is the primary contributor to global carbon emissions. Policy making related to energy booms is therefore also of global relevance. Even if local communities choose not to place restrictions on local energy development, policymakers at higher levels may choose to intervene because of concerns related to global warming. Regardless of the level at which policies are set, the implications for communities with energy resources are likely to remain a significant factor in policy debates.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Grant D. Jacobsen