Elevator pitch

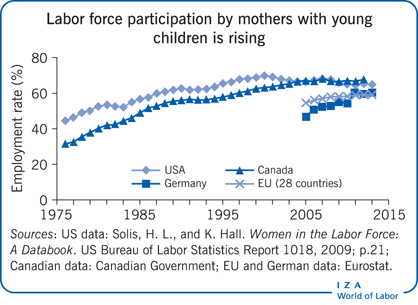

Female labor market participation rates have increased substantially in many countries over the last decades, especially those of mothers with young children. This trend has triggered an intense debate about its implications for children’s well-being and long-term educational outcomes. The overall effect of maternal and paternal employment on children’s cognitive and educational attainment is not obvious: on the one hand, children may benefit from higher levels of family income, on the other hand, parental employment reduces the amount of time parents spend with their children.

Key findings

Pros

Most studies do not find any effect on a child’s short-term or long-term educational attainment from maternal employment.

Fathers’ working behavior does not seem to affect children’s long-term educational attainment.

The quantity of time that parents spend with their children is not decisive for children’s cognitive development or educational attainment.

High-quality time matters, and the amount of high-quality time is barely affected by parental employment.

Cons

Maternal employment during a child’s first year, especially during the first months, might be detrimental to a child’s cognitive development.

Children of highly educated parents may benefit from extended parental leave, while children of less educated parents may even suffer, educationally.

Evidence on the impact of work-related income on a child’s educational attainment is mixed.

Estimates of the effect of parental employment on children’s educational attainment are somewhat conflicting.

The effect of parental employment on children’s educational attainment depends on the quality of non-parental childcare.

Author's main message

There is little reason to worry that increasing labor market participation by women with young children (aged one to six) is detrimental to children’s short-term cognitive skills or long-term educational attainment. There are, however, indications that maternal employment in the first year, and especially the first three months of a child’s life may have adverse consequences for a child’s cognitive development. Instead of focusing on parental employment patterns per se, policy choices should promote high-quality childcare and encourage parents to spend more high-quality time with their children.

Motivation

Knowing whether parental, and in particular maternal, employment has positive or negative effects on children’s educational and cognitive outcomes is important to policymakers charged with the formulation of parental leave, welfare-to-work, or childcare subsidy policies, as well as for parents’ decisions regarding whether to and how much they should work. For example, US welfare reforms in the 1990s pushed welfare-dependent parents to find employment, specifically targeting single mothers. These types of reforms were motivated by the belief that parental work represents the best means of escaping poverty for both parents and children. If, however, having working parents actually hurts the educational and labor market prospects of children, then such reforms may be counterproductive in the long term [1].

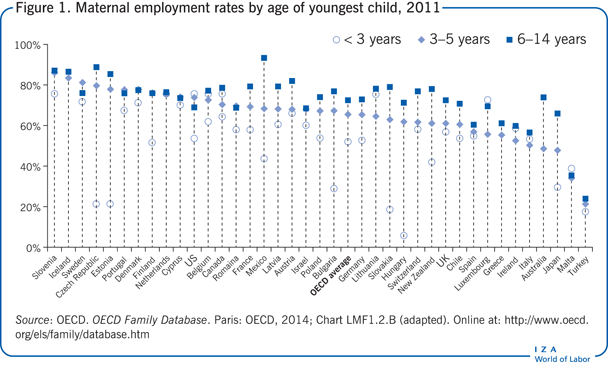

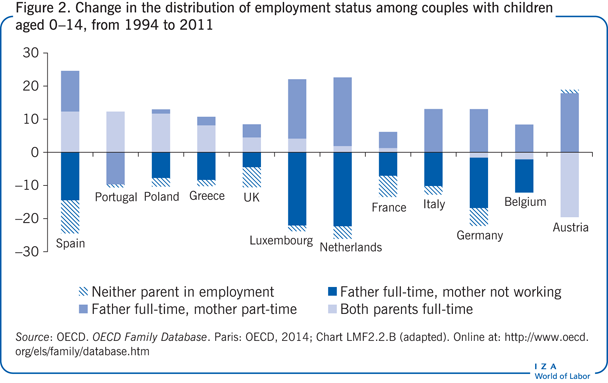

Labor market participation rates for mothers have risen substantially over the last decades. In nearly all OECD countries, more than 60% of mothers whose youngest child is three to five years old are in work (Figure 1). In contrast, variation in the average employment rate for mothers with children below the age of three is much higher across OECD countries, ranging from 6% to 76%. Figure 2 documents that the increase in maternal employment typically implies an increase in the overall hours worked by parental couples with children aged 14 or younger. Fathers’ employment rates have remained fairly stable over the same period. On average, at the EU level, about 90% of fathers with children below the age of six are in work.

How do these trends in parental employment affect children’s development? Linking the effects of parental employment in a causal way to children’s educational and cognitive outcomes is challenging, but crucial for making policy recommendations.

Discussion of pros and cons

Theoretical framework

A seminal contribution to the economic approach regarding child development is the model of skill formation [2]. The skills referenced in this model include both cognitive skills (e.g. IQ) and non-cognitive skills (such as patience, self-control, and perseverance). These skills are the products of investments, environments, and genes. In this model, altruistic parents “invest” in their children; for example, by spending time with them and by paying for childcare, schooling, extra lessons, food, and toys. Governments can also invest in children; for example, by providing publicly funded childcare or schooling. Skill formation is a multistage process, with each stage corresponding to a period in the life cycle of a child. Investments at one stage produce skills at the next. Some stages, so-called “sensitive periods,” may be more productive in producing some skills than other stages, and some inputs may be especially productive at some specific stages, compared to others [2]. A skill produced at an earlier stage has been shown to augment the level of the same skill later on. This effect is termed “self-productivity,” and embodies the idea that the effects of investment early on persist as a child continues to develop [2].

A second key feature of skill formation is “dynamic complementarity”: skills produced during one stage of the life cycle raise the productivity of investment in other skills at subsequent stages [2]. Dynamic complementarity and self-productivity imply that early investments in a child’s developmental process are particularly important. Skills that are formed in childhood and adolescence affect adult choices and outcomes, such as educational attainment and labor market outcomes.

Scope of the evidence

Concerning the empirical evidence, the focus of this article is on educational outcomes (such as grades, test scores, years of schooling, or highest qualification obtained) and not on behavioral or health outcomes. Educational outcomes, in turn, may reflect both cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Given the particular importance of early investments in children’s skills, evidence discussed here is restricted to the effects of parental employment on children when they are relatively young (zero to six). Obviously, this is not meant to imply that parental employment has no effect on older children’s educational attainment. For example, a lack of adult supervision when children are left home alone for long periods due to parental employment could increase school absenteeism, thereby deteriorating educational attainment. Moreover, this paper does not cover the effect of using different types of external childcare. Still, differences in childcare arrangements, particularly the overall quality of external childcare, are likely to affect the interplay between parental employment and child outcomes. Most of the available evidence quantifies the overall effect of parental employment on children’s development. Whenever possible, the impact of more specific parental investments in their children, such as the quantity and quality of time parents spend with their children, or monetary investments, is discussed.

The scope here is also limited to empirical research that has made substantial progress toward estimating causal effects as opposed to only providing findings on correlations between parental employment and children’s academic attainment. Merely comparing the educational attainment of children with working parents to that of children whose parents do not work will yield biased results. This is due to two main reasons: first, parents who work are likely to differ systematically from those who do not work (selection of parents with certain characteristics in the labor market), in ways that may well affect their unobserved ability to support their children’s cognitive development. For example, highly educated parents might be more likely to work (e.g. since they can obtain higher incomes) and, at the same time, they might be better able to facilitate their child’s educational attainment, e.g. to explain school materials or to teach non-cognitive skills such as high levels of patience, perseverance, or self-control that are associated with educational success. A second challenge is potential reversed causality: a child’s initial cognitive ability is typically not observed by the researcher, but parents may condition their employment on their beliefs about their child’s ability. To give an extreme example, parents with disabled children might not work at all, which would induce a negative correlation between parental employment and children’s ability [1].

The effect of maternal employment on children’s short-term outcomes

Overall, evidence regarding the effects of parental employment during a child’s early years on short-term cognitive outcomes is mixed. The majority of studies do not find significant positive nor negative overall effects of parental employment—and if they do, effect sizes are typically small.

Four studies use the same US data set, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), that covers young mothers with an average age of 22 when giving birth [3], [4], [5], [6]. The authors mainly focus on maternal employment during a child’s first three years, measuring, for example, whether mothers worked at all, or the average number of hours worked per week or year. In order to capture children’s cognitive outcomes, these studies rely on test scores in reading and mathematics measured by the Peabody Individual Achievement Test (PIAT-R or PIAT-M, respectively) when children were at least five years old and test scores in the well-established Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) that children took at an average age of three to four. The PPVT is a test of receptive vocabulary and provides an estimate of individual verbal ability. It is often used as a proxy for crystallized IQ that broadly refers to knowledge that has been acquired in life.

Estimation approaches differ across the studies, but all of them aim at addressing selection of parents into the labor market. That means, all studies try to provide causal (instead of purely correlational) evidence on the relationship between maternal employment and children’s short-term outcomes by “correcting” for the fact that mothers with certain characteristics are more likely to work than others (e.g. highly educated mothers or especially poor mothers). One study uses an instrumental variable approach that predicts maternal labor supply by using local labor market conditions (which are independent from a mother’s individual characteristics, but still an important predictor of whether a mother works) and provides results based on predicted maternal labor supply [3]. Two other studies use family fixed effects, i.e. they basically identify the effects of parental employment on children’s educational attainment by comparing siblings who share the same parents and environment ([4] and [5]). Additionally, [4] combines family fixed effects with an instrumental variable approach in order to further increase the robustness of its results.

These three studies neither find strong negative nor significant positive effects of maternal employment on children’s test scores. However, they do document the tendency that maternal employment when their children are very young, that is during the first three months or the first year of a child’s life, has a negative impact on children’s test scores in reading, mathematics, and vocabulary, while maternal employment at ages two or three may even affect these test scores positively. The fourth study in this group uses a different, structural estimation strategy based on estimating parameters of formal economic models, and estimates that one additional year of a mother’s full-time employment when their children are aged one to three reduces their children’s test scores by 1–2%, on average [6].

Moreover, several other studies exploit changes (typically expansions) in parental leave reforms that lead to externally induced variations in parental employment patterns early on in a child’s life. In terms of children’s short-term cognitive development, a study from Canada analyzes the effect of an increase in the number of months that a mother stays at home during a child’s first year [7]. The increase was induced by an expansion in partially paid, job-protected maternity leave, from six to about 12 months. The study uses an instrumental variable approach in which the number of months that a mother stayed at home is predicted according to whether a child was born before or after the change in maternity leave provisions. Staying at home for a longer period of time is not found to have any positive effect on children’s cognitive development at ages four and five (as measured by several test scores, not including PPVT). In contrast, a small, yet significant negative impact is observed on PPVT scores at ages four to five.

The effect of maternal employment on children’s long-term outcomes

Learning about the long-term impacts of early parental employment may be even more important than understanding the impacts on short-term outcomes. Documented short-term effects may turn out to be transient, with no lasting measurable effect on children’s final educational attainment. Alternatively, following the arguments put forth by the model of skill formation, small initial differences among children’s skills and outcomes may expand over time, due to their self-reinforcing nature or dynamic complementarity across skills.

Overall, the picture that emerges from the empirical literature on children’s long-term cognitive and educational outcomes is similar to that for short-run outcomes. Most studies do not find any evidence that parental employment has significant or strong effects on children’s cognitive outcomes. However, there are a few exceptions that document adverse long-term effects of higher parental employment, or alternatively, that reveal benefits from more generous parental leave legislations.

Two studies analyze the effect of individual parental employment patterns across siblings regarding whether children’s educational attainment is sufficient to grant them access to university (i.e. high secondary track, “Gymnasium,” attendance in Germany [1] and obtaining at least one “A-level” qualification in the UK [8]). The estimates in [1] are based on differences in parental employment across multiple siblings within a family, while [8] combines a mother fixed effects estimation with an instrumental variable approach in which maternal labor supply is predicted according to regional and time-based variation in the female unemployment rate. Both studies use data that are representative of the whole population; these data come from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) and the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), respectively. The German study can rule out any meaningful effect size (either positive or negative) from maternal employment at ages zero to three on later educational attainment [1]. In contrast, an additional year worked full-time by a child’s mother at ages zero to five is predicted to decrease a child’s probability of going on to achieve an A-level by 4–11% in the UK [8]. The negative impacts of full-time work in the UK are found to be smaller for more highly educated mothers [8], possibly due to higher income gains or because better-educated mothers seem to spend more of their non-working time with their children.

Evidence based on expansions in parental leave legislation is available for several countries (among others, Germany [9], Denmark [10], Sweden [11], and Norway [12]), and many of the outcomes vary slightly across the studies (e.g. highest degree obtained, high school dropout rates, college attendance, years of schooling, IQ, grades, or even wages and employment). All of the studies first document that changes in parental leave legislation do induce strong changes in maternal return-to-work behavior. Studies [9], [10], and [11] combine regression discontinuity and difference-in-differences approaches. A regression discontinuity approach basically compares after-reform outcomes of children affected by the reform to those that were not affected, typically focusing on a rather tight interval around the cut-off date at which the reform was implemented in order to make the two groups of children as comparable as possible in terms of age and other characteristics. A difference-in-differences approach also compares the outcomes of children affected by the reform to those that were not affected, considering each group before and after the examined reform came into effect. Due to a slow fade-in of the policy change under consideration, study [12] uses a slightly different estimation approach that is also based on leave entitlements. In sum, most of these studies do not conclude that an increase in maternal months stayed at home has any significant effect on children’s long-term educational attainment [9], [10], [11]. There is one notable exception, however. According to registry data from Norway, the increase in maternity leave from 12 unpaid weeks to four months paid and 12 months unpaid, but still job-protected leave, in 1977, reduced children’s high-school dropout rates by about 2% and increased their earnings at age 30 by 5–7% [12]. Compared to the other reforms under study, the Norwegian reform is a relatively long extension of maternity leave starting from a very short duration that is comparable to current levels of maternity leave found in the US. Moreover, there is some evidence that children from higher-educated mothers benefit from extensions in maternity leave while those of lower-educated mothers do not, or that they might even suffer, educationally [11].

The role of fathers

There are only two studies that do not restrict their attention to maternal employment, exclusively; they additionally, and quite explicitly, analyze the role of paternal employment on children’s educational attainment [1], [8]. Similar to results on the effects of maternal employment, neither study finds a significant effect of the father’s working behavior on children’s long-term educational attainment.

The income effect

Most of the available evidence reflects the overall effect of parental employment on child outcomes, but does not attempt to disentangle the effect of time spent with the child from the income effects of parental employment. For example, a higher family income enables parents to pay for more expensive, high-quality child care or schooling, extra lessons, health care, etc. and may reduce stress in the family environment, which, in turn, may positively affect parent-child interactions. This is particularly true for studies based on changes in parental leave legislation. The few studies that do aim at separating time and income effects provide mixed evidence; some of them do not find a significant positive effect of, for example, monthly or yearly household income on children’s cognitive outcomes [1], [6], while others (tend to) do [3], [4]. There is some (limited) evidence that the pure time effect of parental employment becomes more negative for the child’s outcome than the overall effect when separating the time and (positive) income effects of parental employment [3]. This suggests that the overall effect of parental employment can indeed be decomposed into a time effect and an income effect that may independently affect children’s educational attainment.

The time effect and quality of parental time

Due to a lack of data on the time that parents spend taking care of their own children, studies on the effect of parental employment on child outcomes typically implicitly equate an increase in parental hours worked with a decrease in parental time spent on childcare. Only a few studies have detailed information on parents’ time spent with their children and, thus, can explicitly analyze the effect of parental time on children’s cognitive outcomes.

There is no evidence that a higher overall amount of hours spend on childcare per day increases children’s verbal skills, mathematics skills [13], or long-term educational attainment [1]. Using US children’s detailed time-diary data from the Child Development Supplement of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), maternal work is found to reduce a mother’s overall time spent with her child [13]. However, maternal employment has no effect on the amount of time that mothers and children spend involved in activities that positively influence children’s verbal or applied mathematics skills, such as educational activities (for example doing homework or reading). In contrast, maternal employment is shown to reduce the time that mothers and children jointly spend on unstructured activities (including, for example, watching TV or activities reported as “doing nothing”) that are found to be detrimental to children’s cognitive development. Moreover, there is some evidence that fathers react to maternal employment by spending more time on those activities that can positively influence child development, but also on unstructured activities that may be detrimental [13].

Limitations and gaps

While research regarding the effects of parental employment on children’s long-term development may be especially important, it necessarily uses data from past decades. In the past, childcare arrangements beyond the core family (formal, center-based childcare versus informal care by relatives or friends) and the quality of available non-parental childcare likely differed from current childcare options. Differences in childcare arrangements, in turn, may well affect the interplay between parental employment and child outcomes. More generally, all studies use data from a specific context, and mediating factors of the relationship between parental employment and children’s development may differ widely across contexts. Consequently, providing causal evidence on the link between parental employment and child outcomes is a valuable step, but only a first step.

We still largely lack a deeper understanding of the more specific channels that link parental working behavior and child outcomes. More research is needed that analyzes the impact of parental working behavior on child outcomes, taking into account differences in non-parental childcare arrangements, quantity and quality of time that parents spend with their children, the role of household income and parental education, flexibility of parental work arrangements, maternal stress or life satisfaction, social acceptance of working mothers, etc. A deeper understanding of mediating factors between parental employment and child outcomes will probably require the collection of new and extremely comprehensive data sets, specifically designed to address these questions.

A further problem with the current literature is that most US studies (e.g. [3], [4], [5], and [6]) use the same data set, NLSY data, and as such, they cannot provide independent estimates of the relation between parental employment and child outcomes. Additionally, NLSY data are not a representative sample, since they cover only young mothers with an average age of 22.

Summary and policy advice

Empirical evidence on the causal effects of parental employment on children’s educational attainment are somewhat conflicting, with most studies not finding any impact of maternal employment during years one to six on a child’s short-term or long-term educational attainment. In studies that do document positive or negative effects, effect sizes are typically small. Some systematic patterns do, however, emerge from the literature: maternal employment during a child’s very first months is often, but not always, found to be detrimental to a child’s educational attainment. Moreover, children of highly educated parents may benefit from extended parental leave, while children from less educated parents may even suffer, educationally. Time-use data reveal that the mere quantity of time that parents spend with their children is not decisive for children’s development. High-quality time devoted to highly interactive activities matters for child development and the amount of high-quality time is hardly affected by parental employment.

We have purposely restricted our attention in this context to the implications of parental employment for children’s cognitive and educational attainment. Obviously, policy advice should also take into account the potential effects on other dimensions of children’s well-being, such as behavioral or health outcomes (as well as the well-being of parents and society as a whole). Having this caveat in mind, several policy implications emerge from the results presented here.

First, there is little reason to worry that, on average, labor market participation by women with young children (aged one to six) is detrimental to children’s educational attainment. Consequently, policies should not address parental employment patterns per se, but should rather encourage parents to spend more high-quality time with their children, and should promote the development of high-quality childcare.

Second, making high-quality childcare accessible for children from poorer families most likely is an effective means to promote their educational achievement, and, thus, can contribute to more equal opportunities for children from families with different socio-economic status.

Finally, parental leave policies that enable parents to stay at home during a child’s very first months are likely to benefit children’s cognitive development.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Corinna Hartung provided excellent assistance in preparing this paper.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Hannah Schildberg-Hörisch