Elevator pitch

Low-wage employment has become an important feature of the labor market and a controversial topic for debate in many countries. How to interpret the prominence of low-paid jobs and whether they are beneficial to workers or society is currently an open question. The answer depends on whether low-paid jobs are largely transitory and serve as stepping stones to higher-paid employment, whether they become persistent, or whether they result in repeated unemployment. The empirical evidence is mixed, pointing to both stepping-stone effects and “scarring” effects (i.e. long-lasting detrimental effects) of low-paid work.

Key findings

Pros

Having a low-paid job may be better than having no job at all.

Accepting low-paid jobs prevents scarring effects of unemployment that could create long-term problems for the worker.

Low-paid employment may serve as a stepping stone into higher-paid employment, for instance, by improving an individual’s employment-related skills.

For less qualified or long-term unemployed persons, low-paid jobs may offer a suitable way to re-integrate them into the labor market.

Cons

Individuals can be trapped in low-paid jobs.

Accumulation of human capital while working in low-quality jobs is often limited.

Employers may interpret low-paid jobs in an individual’s employment history to be an indicator of low productivity.

Accepting low-paid employment may be a negative signal, particularly for qualified workers, though it may be less of a problem for other unemployed persons.

Low-paid employment can drive individuals into repeated spells of unemployment, which may result in a low-pay no-pay cycle.

Author's main message

Although upward mobility is limited, low-wage jobs can act as stepping stones to better-paid jobs for certain groups of workers. This provides some support for the “work-first” strategy that forms the basis for welfare reforms in many countries. However, as low-wage employment is not a self-correcting problem and can induce scarring effects, a comprehensive policy approach is needed. This should include active labor market policies and a philosophy of lifelong learning that increase workers’ chances to move up to better jobs, as well as a strategy of promoting “good firms” that invest more in training and provide better opportunities for workers to acquire high-paid jobs.

Motivation

In many countries, the existence of a sizable (and often increasing) low-wage sector has become an important feature of the labor market and a controversial topic for debate, particularly when seen against the backdrop of increasing earnings and income inequality. Low-wage jobs are usually defined as those that pay less than two-thirds of the national median or mean of gross hourly wages; as such, being in low-wage employment is not necessarily the result of only working part-time. Although there is some evidence about the specific characteristics that seem to make certain workers susceptible to low-paid jobs, it is unclear how the prominence of low-paid employment in labor markets should be interpreted; likewise, it is a matter of debate whether low-paid work is beneficial to individuals or society. A key issue is the nature of low-wage employment; is it a transitory or a persistent experience in an individual’s working career? In other words, do low-paid workers tend to be trapped in low-wage employment, or can they use those positions as stepping stones to higher-paid jobs?

Discussion of pros and cons

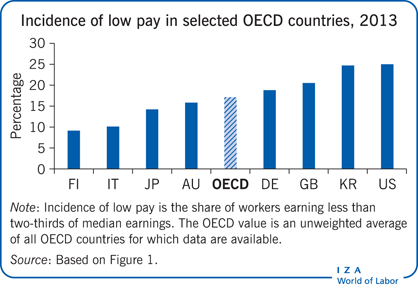

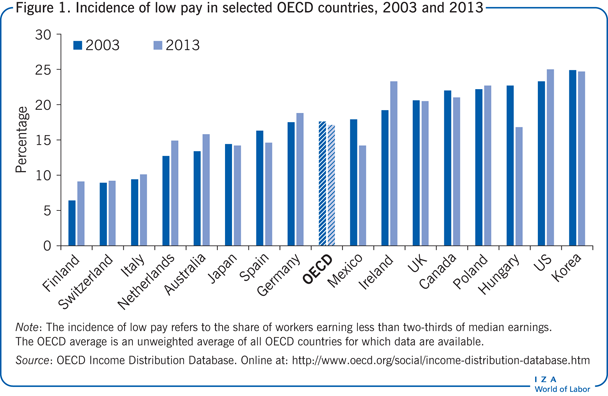

In 2013, about one out of six full-time workers in OECD countries earned wages that amounted to less than two-thirds of the median wage, and were thus regarded as low-wage earners. Figure 1 shows that the incidence of low pay varies considerably among OECD countries. In 2013, it ranged from about 9 or 10% in Finland, Switzerland, and Italy to almost 25% in Ireland, Korea, and the US. Since 2003, the incidence of low pay has increased in some countries and decreased in others. As a result, the (unweighted) OECD average of about 17% has not changed much in the last ten years.

In order to understand low-wage employment and its implications, research has concentrated on three main issues. First, it is important to understand the determinants of being in a low-paid job, i.e. the individual or firm characteristics that are typical for low-wage employment. Second, it is crucial to know whether low-wage jobs are mainly transitory in nature typically leading to higher-paid jobs later on, whether they tend to become persistent, or whether they even result in (repeated) unemployment. Third, low-paid jobs should be compared to other available alternatives; it is particularly interesting to determine if it is better to take up a low-paid job, or to remain unemployed and wait for a better job offer in the future.

The labor market and welfare reforms implemented in the last 20 years across most OECD countries have typically assumed that any work, even if it is a low-paid job, is better than being unemployed and being reliant on welfare. There is some justification for this rationale, particularly if taking up a low-paid job has a good chance of improving an employee’s future pay and working conditions. One major argument in favor of accepting low-paid jobs is that it helps the worker avoid “scarring effects” associated with unemployment (i.e. the worker becomes burdened with negative effects from unemployment that persist over time, acting as a proverbial “scar”) [1]. Prospective employers often regard being unemployed as a negative signal, which may reduce the applicant’s chances of receiving attractive job offers. While unemployed, individuals incur a depreciation of their human capital, and their preferences may change toward engaging in more leisure activities, resulting in a reduction of labor supply [2]. By taking up a low-paid job rather than waiting for a better job offer, individuals reduce their unemployment duration and thus the aforementioned scarring effects. For some groups of workers, such as long-term unemployed or low-qualified workers as well as those that have been out of the labor force (e.g. due to parental leave), low-paid jobs may be a way to re-integrate them into the labor market.

Low-paid employment is particularly acceptable if it is primarily transitory, serving as a stepping stone to better-paid jobs, for instance, by improving employment-related skills. If low pay work is a transitory condition that is spread across the general workforce, this means that earnings inequality will be shared, at least to some degree, among different individuals over their employment life cycle. In addition, if low pay is a transitory phenomenon and acts as a stepping stone to higher pay, there may be less need to maintain an adequate minimum wage than in a situation where low pay is persistent and people are only able to receive an inadequate minimum wage that does not cover their basic needs [3].

However, a totally different appraisal emerges if low-wage employment tends to be persistent, or even leads to a vicious circle of low-paid jobs and unemployment (which is sometimes called the “low-pay no-pay cycle”). Individuals could be trapped in low-quality jobs or be driven into repeated spells of unemployment for a number of reasons. For instance, employers may interpret low-quality and low-paid jobs in a worker’s employment history as an indicator of low (future) productivity [1]. This negative signal should be particularly pronounced for individuals with higher levels of qualifications, reducing their chances of getting a job that corresponds to their formal qualification. Similarly, accumulation of human capital in low-quality jobs is often limited and is probably not much higher than during unemployment, particularly when compared to situations where unemployed individuals receive training measures from the employment agency [4]. For some (qualified) workers, low-pay employment may even be associated with a deterioration of their human capital. Furthermore, on-the-job search for a better job is likely to be more difficult and less effective than when searching during unemployment (e.g. due to time restrictions). For these and other reasons, the experience of low-wage employment may have a genuine effect on an individual’s probability of securing a high-paid job or being unemployed in the future—a phenomenon called “state dependence” in the literature.

If low pay becomes persistent or if it leads to a low-pay no-pay cycle, this implies that low earnings are concentrated in a fraction of the working population who may be excluded from sharing potential economic prosperity [3]. With that said, low pay for individual earners is not necessarily associated with poverty for their respective households, as in most cases, low-paid individuals are not the main or sole earners in their households.

Who are the low-paid?

In general, wages are considered low if they are less than two-thirds of the national median or the national mean of gross hourly wages. This definition of low wages, which has been endorsed by international organizations like the OECD and the EU, avoids the difficulty of defining an absolute level of low pay and facilitates international comparisons. Although other definitions of low pay are used—for instance, the lowest three deciles, or half the mean of the wage distribution—the ranking of countries in terms of low-pay incidence or persistence and the insights from empirical studies seem to be robust to using alternative definitions of low pay [5].

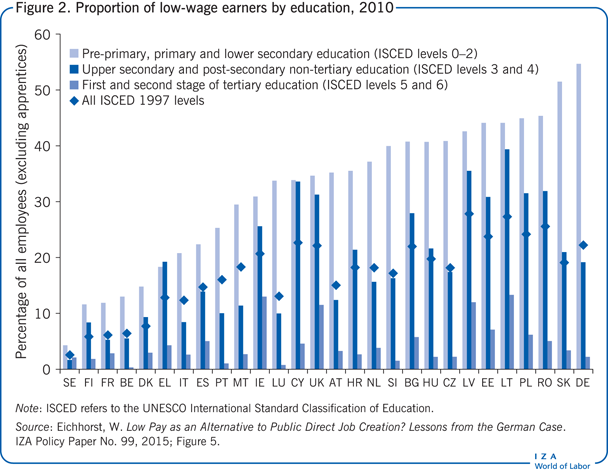

A number of studies across various countries have tried to identify individuals who are low-paid as well as their defining characteristics. Data from the European Community Household Panel (ECHP) 2001 indicate that, among all employees, the incidence of low pay is twice as high for female workers as for male workers [6]. Low-pay incidence is also particularly high for young workers, for those in temporary contracts, and for agricultural workers. The probability of being low-paid tends to decrease with a worker’s qualification level (Figure 2), but it is notable that (in some countries) significant shares of skilled workers are also engaged in low-wage employment. These findings are confirmed by other studies for the EU [5] and for a number of countries like Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain [7]; Germany [8]; the UK [9]; and Australia [3].

Upward mobility of low-paid workers

Having identified the main characteristics of low-paid workers, it is important to know which factors affect the dynamics of low-pay employment; in other words, do workers typically remain in low-paid jobs or are they able to move up to better-paid jobs? Studies for a number of countries show that workers in low-paid jobs are quite likely to remain in low-wage employment from one year to the next. For instance, data from the ECHP indicate that, across the EU-15 countries, about half of those workers who were low-paid in 2000 were still low-paid in 2001, whereas 31% managed to obtain wages above the low-wage threshold and almost 18% moved into non-employment [6]. Taking into account a longer time perspective of five years, 30% of the low-paid workers from 1994 remained in this state, while 43% managed to increase their wages above the low-pay threshold (and 27% ended up in non-employment). Using the same set of data, a comparative analysis of male workers in 12 EU countries during the period 1994−2001 finds that the probability of a worker remaining in low-paid employment over two successive years varied from 49% (in Spain) to 70% (in the Netherlands) [5]. The authors of this study point out that, in general, countries with a relatively large share of low-paid workers also seem to be those countries where it is most difficult to move out of low-wage employment.

More detailed empirical analyses for various countries indicate that a number of factors influence labor market transitions from low to higher pay. These include individual characteristics as well as sector-specific, occupational, and establishment characteristics. Furthermore, the overall state of the labor market and labor market policies (such as training and public employment policies) may play a role too.

Concerning individual worker characteristics, not only is low-wage employment more prevalent among female and low-skilled workers, but the chances that these groups are able to escape from low-paid jobs are also generally more limited [6], [7], [8]. In contrast, younger workers at the beginning of their careers exhibit a higher probability of moving up the wage ladder than older workers [6], [8].

The characteristics of the employing firms are also significant for low-wage earners’ chances of achieving higher paid jobs. In Germany, chances are better in larger industrial plants, which more frequently offer training and other possibilities for workers to accumulate human capital than smaller plants [8]. Moreover, plants with a high share of low-paid workers appear to be dead ends for individual low-paid workers, since the chance of upward wage mobility in these plants is significantly lower [8]. Sectoral affiliation also seems to play a role; workers in agriculture are particularly unlikely to leave their low-wage jobs, whereas workers in the public sector seem to have better chances of securing higher paid jobs in the future [6].

Interestingly, there is no clear-cut evidence on how overall economic conditions and the state of the labor market affect transitions from low-paid to high-paid employment. Having said that, a study for the EU-15 countries reports a small dampening effect of higher unemployment rates on transitions from low- to high-paid jobs between two successive years (but no effect is seen on transitions over three years) [6]; additionally, an empirical investigation for Australia suggests that transitions between various labor force and earnings states are lower under weak than under strong economic conditions [3]. With respect to the role of labor market policies and firms’ human resource management policies, transitions from low to higher pay are more likely for those workers who have received training or vocational courses [5], and in particular for those that get on-the-job training [7].

Stepping stone and scarring effects of low-paid jobs

When interpreting the evidence on pay transitions, it is important to distinguish between the heterogeneous characteristics of workers that predispose them to low-paid jobs and the direct causal effects of low-paid employment on the probability of being low-paid, high-paid, or unemployed in the future. As discussed above, accepting a low-paid job may induce scarring effects by sending negative signals to prospective employers, by being associated with a deterioration of human capital, or by reducing workers’ search intensity. It is thus important to find out, for an unemployed individual, whether it is better to take up a low-paid job or to remain unemployed and wait for a better job offer at some later point.

By estimating models that account for the fact that people who accept low-paid work are a selected subgroup (mostly based on the analytical tools and concepts developed in [10]), some empirical studies have tried to assess if low pay during a particular period in a worker’s career path has a genuine effect on his/her likelihood of being in certain labor market states in the future, even after accounting for worker characteristics that predispose them to low pay. A number of studies find that having been employed in a low-paid job does indeed seem to have a genuine effect on the probability of being low-paid, high-paid, or unemployed in the future—a phenomenon called (true or genuine) state dependence in the literature. For instance, low-pay state dependence is found in all 12 EU countries examined by a comparative study of male workers, even after individual worker heterogeneity is accounted for [5]. State dependence is also found in a study of male workers in the UK which compares various methods of estimating the transition probabilities into and out of low-paid employment [9]. Another study about British men shows that low-paid jobs have almost as large an adverse effect as unemployment on future employment prospects [11], leading to the conclusion that low-wage jobs are a conduit to recurring unemployment in the UK.

In contrast, more recent evidence from outside of the UK suggests that, although substantial scarring effects from unemployment exist, low-paid jobs tend to improve workers’ employment and income prospects compared to being non-employed. Two Australian studies make clear that both state dependence and stepping stone effects of low-wage employment can be present [3], [12]: Workers in low-paid jobs are more likely to be in low-wage employment in the future compared with individuals who are not in the labor force, are unemployed, or are in higher-paid jobs. However, low-paid workers are also more likely to move into higher pay in the future than those who are unemployed or those not in the labor force. For Germany, two studies show that the chances of obtaining a high-paid job by accepting low-paid work improve most strongly for those who have experienced longer periods of unemployment and for those who are less-skilled [13]. On the other hand, for individuals with medium or high qualification levels, the risk of non-employment in the future is not significantly lowered by taking up a low-paid job instead of remaining unemployed [2]. The latter result stands in contrast to an Australian study that reports less severe penalties from low-paid employment for better-educated workers [12].

Focusing on women, who constitute a disproportionate share of low-wage earners, another study for (western) Germany finds genuine state dependence in low-wage employment: having a low-paid rather than a high-paid job decreases the probability of being highly-paid in the future, and this negative effect is particularly strong in part-time jobs. Only for part-time workers, low-wage employment also increases the risk of being unemployed in the next period. With respect to future wage prospects, however, low-paid women are found to be significantly better off than unemployed or inactive women. The authors argue that, for women, low-wage jobs can help lead them out of unemployment and that these jobs should be prioritized over remaining unemployed while waiting for a better job [4]. An Australian study provides corroborating evidence that low-paid employment is always preferable to unemployment for women [12].

A careful interpretation of the empirical evidence across a number of countries thus allows three main conclusions. First, there is some evidence for state dependence regarding low-paid work in many countries. Being in low-wage employment today seems to have a genuine influence on the probability of being low-paid (as well as the probabilities of being high-paid or unemployed) in the future. However, since observed state dependence might not necessarily imply causality (for instance, due to selection issues, estimation problems, and lack of data), some caution with interpretation is clearly advisable. Second, although upward mobility appears to be limited, low-wage employment is not a persistent experience or a dead end for all low-wage earners. Low-wage jobs can act as stepping stones to better-paid jobs for some groups of workers. Third, empirical evidence on the existence of a low-pay no-pay cycle is mixed: compared to being highly-paid, some studies find that having a low-paid job increases the risk of being unemployed in the next period, or that this is the case for specific worker groups [4], [11], [12], while in other studies [3] or for other demographic groups [12], this relationship is not observed.

Limitations and gaps

Most studies dealing with the transitions into and out of low-paid jobs treat low pay as a binary variable (i.e. an either/or condition); they generally only distinguish between being paid less than or more than a certain threshold. This has certain limitations: first, being paid slightly above the low-wage threshold of two-thirds of the median wage, or moving up the ladder to a job that offers a wage only slightly above this threshold, does not mean that workers do indeed receive high wages. A second related issue is the extent to which wages of persons moving out of low-wage employment typically rise above the low-wage threshold, but this question has rarely been investigated. Third, although the rough probabilities of leaving low-wage employment from one period to another are known, there is not much evidence on how permanent such moves to higher-paid jobs are, nor whether workers are likely to fall back into low-paid jobs in the future.

It should also be kept in mind that the results from complex empirical investigations on the transitions into and out of low-paid employment might, to a certain degree, depend on the data and econometric methods used [9]. As quite a few influential multi-country studies are primarily based on data from the 1990s [5], [6], conducting similar studies with more recent data should provide a better understanding of the current role of low-wage employment, which may have changed over time. These types of multi-country comparative studies should also more deeply investigate the role institutional factors such as collective bargaining, minimum wages, and active labor market policies play for (transitions out of) low-paid employment, for which empirical evidence is very limited. Likewise, although some recent studies have started to look at variations among the impacts of previous labor force statuses for different demographic groups [2], [4], [12], further evidence is still needed about how “atypical employment” such as part-time work, fixed-term employment, and temporary agency work affects the upward wage mobility of low-paid workers.

Summary and policy advice

The empirical literature suggests that low-wage employment is not a persistent experience for all low-paid workers. Although upward mobility appears to be limited, low-wage jobs can act as stepping stones to better-paid jobs for some groups of workers, and do not necessarily lead to non-employment. These findings could be interpreted as providing some support for the work-first strategy that many countries have adopted in their labor market and welfare reform policies.

However, the empirical evidence also indicates that low-wage employment does not seem to be a self-correcting problem. For instance, staying in the “wrong” kind of firm (in particular small firms and those with a high share of low-paid workers) can make low-wage employment a persistent condition. This implies that labor market policies which seek to improve low-wage earners’ access to higher-wage firms and occupations could reap substantial payoffs. Providing the right kind of skills and improving job search strategies may allow low-paid workers to more easily transition between jobs and climb the proverbial ladder to achieve higher earnings.

Quite a few studies show that the significant risk for low-paid workers to be low-paid or unemployed in the future is, to a large degree, not caused by experiences in low-paid jobs; rather, it is mainly due to the workers’ personal characteristics (such as insufficient skills), which inhibit their success in the labor market. This problem calls for labor market policies that provide training and better skills to these disadvantaged workers. Moreover, public policy needs to place more emphasis on early childhood development and education in order to prevent individuals from being disadvantaged at the start of their working life.

A comprehensive approach to improving low-paid workers’ chances in the labor market should rest on two pillars: first, an empowerment strategy should be adopted based on active labor market policies and lifelong investment in education and training; this may strengthen workers’ individual bargaining positions with employers and increase their chances to move up to better jobs. This approach should be complemented by a second strategy of promoting so-called “good firms,” which invest more in further training of their workers, are more productive, and provide better chances of high-paid jobs. In a wider sense, this calls for creating a well-functioning business environment in which productive firms prosper, while low-road business strategies relying on cheap labor are abandoned.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Alexander Mosthaf. Previous work of the author (together with Alexander Mosthaf, Thorsten Schank, and Jens Stephani) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used in some parts of this article [4], [8].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Claus Schnabel