Elevator pitch

Many OECD countries have, or have had, a policy that exempts older unemployed people from the requirement to search for a job. An aging population and low participation by older workers in the labor market increasingly put public finances under strain, and spur calls for policy measures that activate labor force participation by older workers. Introducing job search requirements for older unemployed workers aims to increase their re-employment rates. Abolishing the exemption from job search requirements for the older unemployed has been shown to initiate higher outflow rates from unemployment for them.

Key findings

Pros

Studies show that introducing search requirements for older unemployed people in the Netherlands increases their outflow rate into jobs.

The financial strain imposed by older workers on the unemployment insurance system is reduced if older workers are re-employed sooner.

Evidence shows that older unemployed workers in Germany receive higher reservation wages if they are exempted from job search requirements, indicating a reduced incentive to accept jobs.

Monitoring and sanctioning stimulate the unemployed to meet their search requirements.

Cons

Evidence for the Netherlands shows a side effect of job search requirements in the form of an increased outflow of older unemployed into sickness and disability insurance schemes.

Monitoring and screening the search efforts of older workers involves additional implementation costs.

For older workers with a skill mismatch and a long-term unemployment spell, job search effectiveness can be limited.

Re-employment problems of older workers due to restrictions from the demand side of the labor market cannot be solved by search requirements.

Author's main message

Policies aimed at activating older workers are particularly important for many OECD countries with aging demographics. Empirical evidence suggests that removing exemptions from job search requirements for older unemployed people will increase their flow out of unemployment and into jobs. A possible negative side effect from this action is the increased flow from unemployment into inactivity, such as disability. Overall, job search requirements for the older unemployed, in combination with a system of monitoring and sanctioning that guarantees their credibility, can lead to improved re-employment for older workers.

Motivation

Many OECD countries have, or at some point have had, a policy that exempted older unemployed people from the requirement to search for a job, without consequences regarding their eligibility to receive unemployment insurance benefit payments. Such policies have often been motivated by the presumed poor job opportunities for older workers, and the desire to make space for younger entrants in the workforce. Exempting older unemployed workers from search requirements reflects the spirit of the 1980s, in which fairly generous early retirement schemes were also established. At present, an aging population, in combination with a low participation rate by older workers, increasingly strains public finances and has already led some countries to increase their official retirement age to 67. Some countries, including the Netherlands, have abolished the exemption from job search requirements for older unemployed workers. Due to this reform in the Netherlands, older unemployed workers have experienced higher re-employment rates. The effectiveness of imposing job search requirements onto older workers is affected by a larger package of policy measures aimed at enhancing their participation rate, including penalties for not meeting search requirements, the barring of alternative exit routes such as disability insurance and early retirement, and wage subsidies that increase job opportunities for older workers.

Discussion of pros and cons

Abolishing exemptions from job search requirements for older unemployed workers

In many countries, including Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, and the UK, older unemployed workers have been, at some stage, exempted from looking for work [1], [2]. However, there has been a tendency internationally toward increasing the age at which older workers are exempted from search requirements (Belgium increased the age from 50 to 58), or toward abolishing the exemption entirely, as France did in 2012 and the Netherlands in 2004. Prohibiting the unemployment insurance system being used as a pre-retirement exit route from employment in part motivates this tendency [3].

The Netherlands case is particularly interesting because the re-introduction of search requirements for older workers in January 2004 allows for a detailed policy evaluation, where the situation before and after the reform can be compared using treatment and control groups [1]. The inflow rate of older Dutch workers into unemployment is typically low, which is often attributed to employment protection legislation that is particularly favorable for older, highly tenured workers. Although this legislation is not particularly designed to protect older workers, it works in their favor.

Once unemployed, the outflow rate from unemployment is also low for older workers, leading to relatively long unemployment durations [2]. There are various explanations for this, but long unemployment insurance benefit entitlement periods for older workers and the exemption from search requirements are potential attributes. In the Netherlands, for instance, workers aged 56 or older were eligible for wage-related benefits for up to five years. The additional flat rate benefit entitlement period was two years, but increased to 3.5 years if workers reached the age of 57.5. (In July 2015, the maximum entitlement period for the wage-related unemployment insurance benefit was reduced to 24 months, as part of a larger package of labor market reforms (Wet Werk en Zekerheid).) In practice, this meant that from a certain age, workers could use unemployment benefits to bridge the period from inflow into unemployment to the official retirement age of 65. Before January 1, 2004, older unemployed workers were exempted from the requirement to search for new jobs as soon as they reached the age of 57.5. From 2004 onwards, unemployed workers were required to search, though the entitlement period and replacement rate remained the same.

In practice, search requirements are imposed by a system of monitoring and sanctioning. (More details about the Dutch search requirement system are described in [1].) Eligibility for unemployment insurance benefits includes a requirement to apply for at least four suitable jobs every four weeks, where suitability depends on criteria like required education level, earnings compared to the previous job, and commuting time. Every four to six weeks, the unemployed worker must show up at the employment office and report on their efforts. If the search effort is deemed too low, sanctions can be imposed, up to a reduction in the unemployment insurance replacement rate of 20%. This relatively large cut in maximum benefit levels is actively imposed [1], indicating that the possibility of being sanctioned is more than just a threat. Imposing search requirements on the older unemployed implies that they will become subject to this system of monitoring and sanctioning. (More information regarding the effect of sanctions in the unemployment insurance system can be found in [4].)

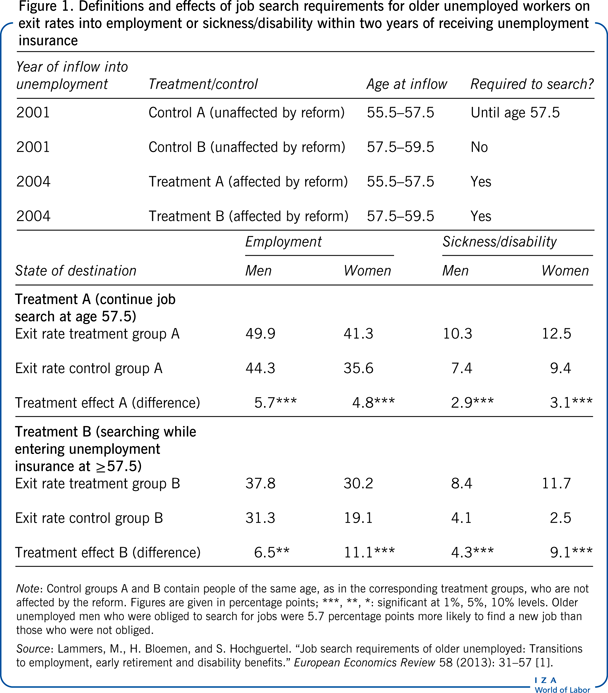

The policy reform affected different age groups. The first was composed of workers aged 57.5 or older who became unemployed after January 1, 2004 (treatment B in Figure 1). The second was unemployed workers who were younger than 57.5 on January 1, 2004, who must continue searching for jobs if they are still unemployed when they reach the age of 57.5 (treatment A). This specific combination of reform date and ages has been exploited to study the impact of search requirements on the outflow of these groups from unemployment [1]. In addition to examining the outflow from unemployment into jobs, the flow into two alternative destinations has also been examined: the sickness/disability insurance scheme and the early retirement system. The intention with job search requirements is to activate older unemployed workers and get them back into work, but an unwanted side effect may be that they disappear into states of inactivity, instead. However, entering those alternative states can only happen if they satisfy eligibility criteria.

Figure 1 shows how the treatment and control groups are set up in [1]. Inflow into unemployment from 2001 is included as a pre-reform control group, and inflow from 2004 captures the post-reform period. The age range of individuals in the sample runs from 55.5 to 59.5.

All the unemployed flowing in at year 2001 face the old, pre-reform regime. From the year 2004 onwards, depending on age, individuals will be affected by the new regime. Treatment A indicates the effect on the unemployed who enter unemployment before the age of 57.5 and who need to continue searching after the age of 57.5, while before the reform this age group (control A) could stop searching at that age. Treatment B indicates the unemployed who enter unemployment at the age of 57.5 or older and who need to search for a job upon entry into unemployment due to the reform, while the same age group before the reform (control B) was exempted from searching. An additional treatment is imposed upon the unemployed who entered unemployment during 2004 at an age of 57.5 or older and initially were not required to search because they entered before the reform, but from the date of the reform on, they need to start searching [1].

Using a competing risk duration model, that is, a model for unemployment duration that allows for various exit states, the impact of the various treatments on the transition rate out of unemployment into the states of employment, sickness/disability, and early retirement has been estimated (controlling for such factors as: education level, age, marital status, presence of children in the household, nationality, seasonal effects, and unobserved heterogeneity).

The estimation results were used to isolate the treatment effect expressed in terms of the exit rate within two years from unemployment to the various destination states (Figure 1). The period of two years was chosen because after two years hardly any exits from unemployment take place.

The results for the state of (early) retirement are omitted from Figure 1, as no significant effects on the transition into early retirement were found for either treatment. Treatment A increases the exit rate from unemployment into a job within two years by around 5% to 6%, for both men and women. The effect for treatment B on entering employment is even larger, especially for women. The discovery of a positive effect due to the introduction of search requirements for older workers on their exit rate into jobs is a desirable result of the policy reform.

Figure 1 also shows that treatments A and B led to a higher exit rate into sickness and disability schemes, although the percentage point changes are lower than for employment. This seems an undesirable result of the reform, because sickness and disability schemes move individuals further away from an active position in the labor market. However, it should be noted that individuals can only enter the state of sickness/disability if they satisfy the eligibility conditions. It is possible that some of the unemployed entering disability before the reform took hold preferred to be on unemployment insurance, for instance because pension accumulation continues when receiving unemployment insurance.

While the results show a positive increase in exit rates for older workers into jobs, little is known about the quality of the jobs that older unemployed people with job search requirements transit into. An important aspect of a job is the wage earned. Imposing search requirements may lead to a reduction in older workers’ reservation wages (the wage at which they are willing to accept a job offer), inducing the unemployed to more easily accept lower-paid jobs. This could show up in the distribution of observed accepted wages. In the above study, accepted wages before and after the reform for different age groups (treated and controls) are compared, but no systematic differences can be detected [1]. On the basis of the observed accepted wages, it can therefore not be concluded that lower reservation wages were an important mechanism in the increased exit rates due to the abolishing of job search requirements for the older unemployed. A study of prime-age workers in Switzerland also finds no effect of job search requirements on accepted wages, but the authors do find a very small negative effect (–0.3%) on the duration of re-employment spells [5].

The emphasis of the earlier study is on the flow out of unemployment [1], but there is evidence that strategic timing of entry into unemployment is affected by the presence or absence of search requirements. Before abolishing the exemption from job search requirements, there was a more pronounced peak in the number of entrances into unemployment by those 57.5 or older than has been observed thereafter [6], [7].

Global empirical evidence on search requirements for the unemployed

In the UK, a reform in the Job Seekers Allowance (JSA) took place in 1996, which, among other things, included an increase in job search requirements in order to be eligible for unemployment insurance. The effects of the reform were studied and published in 2009 [8]. However, this increase in job search requirements holds for all unemployed people and the study is therefore not specifically directed toward older workers. Comparable to the results from the Netherlands [1], search requirements in the UK are successful in removing individuals from unemployment insurance benefits, but this has been largely attributed to a shift into the incapacity benefit scheme. This example shows that tightening of the job search requirements for unemployment insurance benefits should be combined with analyzing the eligibility criteria for potential alternative destination states.

Job search requirements for older workers have also been analyzed for Germany [9]. However, the subject of this study is not exit from unemployment or the state of destination, but subjective information on the reservation wage. In Germany, older unemployed people had the possibility to be exempted from job search requirements starting at the age of 58. Utilizing a cross-sectional sample from 2005, the authors focus on the fact that at the age of 58 the requirement to search for a job is halted (a so-called regression discontinuity design) [9]. The main finding is that the elimination of job search requirements at the age of 58 increases reservation wages. This implies that incentives for older unemployed people to accept a job are affected by the presence or absence of search requirements. Lower reservation wages due to job search requirements could imply increasing exit rates from unemployment into jobs.

Another study of the introduction of job search requirements for older workers in the Netherlands adds self-employment as a separate labor market state, analyzing whether self-employment is used as a substitute for unemployment due to the introduction of search requirements [7]. The authors of the study find that search requirements increase the transition rate from unemployment to self-employment, but the proportion of self-employed in total employment remains unaffected.

While previous studies ([1], [7]) measure job search requirements based on a policy change that increases search requirements, another study uses variation in search requirements set at the individual level by individual case workers, exploiting administrative data on unemployment inflow in the period 2010–2014 for Switzerland [5]. This study focuses on prime-age workers, rather than older workers. This allows the study of the impact of differences in minimal required numbers of applications on actual applications, on unemployment, and non-employment duration. Importantly, the authors instrument the required number of job applications set by a case worker for an unemployed worker by the average number of applications that case worker requires from other unemployed workers in the data. This allows the intensive margin of job search requirements to be measured, that is, in terms of the number of required applications. The authors find that one more application required per month reduces unemployment and non-employment duration by 3%.

Monitoring and sanctioning in tandem with job search requirements

The success of search requirements in generating exits of older workers from unemployment into employment depends on enforcement of the search requirements. Enforcement can be achieved by a system of monitoring and sanctioning. It has been shown that sanctioning can have a sizable impact on the transition from unemployment into employment [4]. The underlying mechanism is not just the actual imposition of a sanction, but also the hypothetical possibility of getting sanctioned in case not enough effort is spent on job searching, which can be enough to activate unemployed searchers. Therefore, it is important to realize that a system of search requirements can only be credible if it is accompanied by a system of monitoring and sanctioning.

In some countries, like Sweden, there are job search requirements for older unemployed workers, but they are not strictly enforced [2]. In the Netherlands, from 2002 to 2006, the average magnitude of actually imposed sanctions due to noncompliance with the required number of job applications was a decrease of about 21% in unemployment insurance benefits for an average period of 14 weeks [1]. This is a sizable amount. In the same period, the percentage of individuals on unemployment insurance that were sanctioned was about 8–9%, while around 45% of those were sanctioned for noncompliance with the required number of job applications. These numbers are not separately available for age groups, but they show that in 2004 the percentage of individuals that were sanctioned for not meeting the job search requirements increased, revealing the actual imposition of job search requirements for older unemployed people.

Monitoring and sanctioning, while shown to help boost re-entrance of the unemployed into the labor force, incur costs for society. For example, the implementation of the administration necessary to register and screen the actions of the unemployed, which includes payments made to those screening workers and costs of computer systems for the actual registration.

Impact of the attractiveness of unemployment on imposing job search requirements

Another important factor in determining the effectiveness of imposing search requirements on the older unemployed is how attractive the state of unemployment is for older workers, including, critically, the length of time for which they can receive unemployment insurance benefits. In the Netherlands, before January 1, 2004, the entitlement period for unemployment insurance benefits depended on the potential labor market history of benefit claimants, meaning that the entitlement period was almost fully age-dependent [1]. This meant that the unemployed aged 57.5 or older had an entitlement period for wage-related benefits (with a replacement rate of 70%) of five years, almost enough to bridge the entire gap to the full retirement age of 65.

Studies for some countries show that older unemployed people are more sensitive to changes in the length of the benefit entitlement period than younger people. The impact of an extension of the entitlement period for Austria shows that one week of additional entitlement, on average, leads to 0.7 weeks of additional benefit claims for workers older than 50, while for workers in the age range of 40–50, the additional duration of unemployment insurance benefits is 0.35 weeks [10]. In Finland, one study on the effect of reducing the entitlement period notably shows a decrease in the unemployment duration for the older unemployed [11].

Some countries explicitly grant extended unemployment benefits to older workers, as for instance in Austria between 1988 and 1993 [12], providing a strong incentive to withdraw early from the labor market. Granting older workers extended benefits as a form of pre-retirement seems at odds with job search requirements for older workers, and it is hard to imagine that it is efficient to have both policies in place at the same time.

Evidence of program substitution (i.e. the phenomenon that people who, due to stricter rules, are no longer eligible for one insurance program select themselves into another program) due to the introduction of job search requirements has been found in several studies [1], [8], [12], [13]. A job search monitoring program focused on the long-term unemployed below the age of 50 in Belgium increased the inflow into disability insurance in the country [13]. The study uses a regression discontinuity design comparing unemployed people just below the age of 50 with those just above. Thereby the targeted group is different from earlier studies [1], but again provides evidence of spillover effects to disability insurance.

Alternative causes of program substitution between disability and unemployment are changes in the strictness of medical screening and eligibility rules in the disability insurance system, which are also documented in the literature, for the US [14], and the Netherlands [15].

The incidence of long-term unemployment for older workers is relatively high

The effectiveness of job search requirements can be limited for the long-term unemployed. Job-finding rates typically decrease with unemployment duration [1]. This means that, on average, an individual's job search will become less effective the longer they remain unemployed. In the case of the Netherlands it is shown that job-finding rates are close to zero after two years [1]. Evidence shows that the incidence of long-term unemployment among older workers is relatively high, and that mismatch of skills is a possible reason for long-term unemployment [3]. Similarly, job search can only be effective if it leads to an employee–employer match. Restrictions at the demand side of the labor market limit the chance that a match will be established [3].

Limitations and gaps

The evidence shows that the incentives for older unemployed workers to search for a job are affected by imposing search requirements, and exit from unemployment into a job increases after abolishing the exemption from search requirements. However, those who advocate for the introduction of job search requirements for older workers will, at some stage, be confronted with an overwhelming amount of anecdotal evidence of older workers who sent out dozens of application letters without achieving any result. Especially in times of crisis, there is a push to exempt the older unemployed from job search requirements, as was the case in the 1980s. At the same time, it is important to realize that the demographic composition of the population today is very different from the 1980s, and empirical evidence that the exit of older workers from the labor force leads to jobs for younger generations is lacking. An overrepresentation of older workers among the long-term unemployed cannot solely be attributed to a lack of search effort on their part and a long period of unemployment insurance benefit entitlement [3]. Employers typically face a trade-off between wages and productivity, both of which depend on age. Wages tend to rise with tenure, which is strongly related to age, but also depends on age, independent from tenure. Productivity can be age-dependent in a variety of ways, especially for physical labor, where a negative relation to productivity is often assumed. Also, the skills of older workers may be outdated due to technological progress. On the other hand, older workers have accumulated experience and specific skills, which make them valuable to potential employers. This suggests that there can be a lot of variation between older workers and their potential in the labor market.

On the cost side, wage subsidies can be used to stimulate employers to hire older workers. In the Netherlands, a limited wage subsidy for unemployed workers of age 56 and older exists, but the amount is too small to have a significant effect. This type of policy is also in contrast with the view that age-dependent rules, such as search requirements, wages, and severance payments, should be phased out as much as possible [3].

Another source of variation that affects the supply side of the labor market is private wealth holdings of older workers. Such holdings can influence the incentives of older workers to exit the labor force, although workers with a higher risk of job loss may appear more often among the less wealthy. Again, this shows that variation between older workers is an important issue when it comes to re-employment.

An objection against job search requirements for older workers is the administrative costs of screening and monitoring that they bring, not just for the job searcher, but in particular for the public administration. Indeed, eliminating implementation costs is one of the major arguments by proponents of a basic income. The basic income approach implies the disappearance of any search requirements, not only for older workers.

Summary and policy advice

Empirical evidence shows that abolishing the exemption from job search requirements for older unemployed people leads to an increase in the flow of older workers out of unemployment and into jobs. This is an important result, since it refutes the one-sided view that older unemployed workers cannot find new jobs, and that therefore job searching makes no sense for them. Policies that aim at activating older workers are important in an aging society, even in times when these policies are under pressure due to economic stagnation, particularly because aging is a longer-term structural demographic trend in many OECD countries. A system of monitoring and sanctioning that guarantees the credibility of the job search requirements can improve the efficacy of this policy.

On the other hand, the introduction of search requirements for the older unemployed can also cause adverse effects. In particular, it can lead to an exit from unemployment into states of inactivity, such as, for instance, the disability insurance scheme. Therefore, alternative pathways and their eligibility conditions should be taken into consideration when thinking about job search requirements for the older unemployed. If eligibility conditions are strict enough, a higher inflow into disability as a result of imposing job search requirements need not necessarily be an adverse effect, if this is just a reflection of getting the right people into the right systems.

With respect to incentives on the supply side of the market, it is important to investigate whether entitlement periods for older unemployed workers are so long that unemployment insurance essentially serves as a pre-retirement system. But then, even with job search requirements and appropriate entitlement periods, the older unemployed are at a higher risk of ending up in the pool of long-term unemployed.

There is considerable variation among the older unemployed; on the one hand, there are employable, highly skilled workers with valuable experience, and on the other hand, there are unproductive manual workers and workers with outdated skills. There is still little evidence on the effect of wage subsidies meant to encourage the re-employment of older unemployed workers, for instance in the form of decreased employer premiums and taxes, nor regarding how large wage subsidies should be in order to be an effective instrument.

Overall, it is clear that job search requirements alone, although very helpful, are not enough to re-employ certain segments of the older unemployed; policies designed to help reduce the wage–productivity gap for older workers deserve attention as well.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Marloes Lammers and Stefan Hochguertel for the rewarding collaboration on these issues. Version 2 of the article includes evidence on transitions from unemployment to self-employment and also into disability, plus evidence on how case workers can affect re-employment rates, and includes new “Key references” [5], [7], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Hans Bloemen