Elevator pitch

Ample empirical evidence links adverse conditions during early childhood (the period from conception to age five) to worse health outcomes and lower academic achievement in adulthood. Can early-life medical care and public health interventions ameliorate these effects? Recent research suggests that both types of interventions may benefit not only child health but also long-term educational outcomes. In some cases, the effects of interventions may spillover to other family members. These findings can be used to design policies that improve long-term outcomes and reduce economic inequality.

Key findings

Pros

An array of medical treatments and public health interventions provided during early childhood results in better health in childhood and adulthood.

Early-life medical treatments and public health interventions improve academic achievement later in life.

At-risk children especially benefit from these interventions, which may reduce inequality.

The benefits of early-life interventions seem to extend to other family members as well.

It may be more productive to shift the policy discussion from increasing the number of prenatal or postnatal nurse home visits to the effects of the timing and quality of care.

Cons

For low-risk children, the evidence on the benefits of early-life medical interventions is mixed.

While certain public health interventions have well-documented health returns, little is known about their impact on human capital accumulation.

More research is needed to understand the causal pathways leading to the positive gains from early-life interventions.

More research is needed to understand the interactions between the effects of medical care and public health interventions.

Author's main message

Early-childhood medical treatments and public health programs improve children’s lives and reduce child mortality. While the evidence is convincing that interventions lead to better health outcomes and to improved academic achievement later in life for at-risk children, the evidence is mixed on the impact on low-risk children. Policymakers should carefully consider potential differences in responses to public health programs across population groups when designing such interventions.

Motivation

A large body of empirical research shows that adverse conditions (such as poor nutrition, illness, in-utero alcohol exposure, iodine deficiency, major injuries or mother's bad health, and psychological stress) during early childhood (the period from conception to age five) have long-lasting negative effects on human capital accumulation and economic outcomes as well as on adult health. However, it is unclear whether these negative consequences can be alleviated or eliminated through medical care and public health programs aimed at improving prenatal and early-childhood health.

This is an important question from a public policy perspective and is the focus of this review. An overview of the findings in the literature linking early-childhood health to academic achievement is followed by a discussion of the research on the effects of early-life medical care and public health policies on the human capital accumulation of children. Because of the stark differences in the organization and delivery of health care between developed and developing countries, the focus is limited to studies on developed countries. In addition, with a few exceptions, the focus is on studies that employ data from the mid-20th century onward.

Discussion of pros and cons

Early-childhood health and human capital accumulation

The so-called “fetal origins” hypothesis, put forward by epidemiologist David J. Barker in the early 1990s, posits that the origins of many chronic degenerative adult health problems (such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease) can be traced to in-utero conditions, in particular to inadequate nutrition. Subsequent theories emphasize the impact of early-life postnatal conditions, as well as the in-utero environment, in shaping long-term outcomes. In economics, James Heckman and colleagues formalized this idea in a model that incorporates dynamic complementarities between inputs across different stages of life, showing how skills acquired early in life increase the productivity of investments later on.

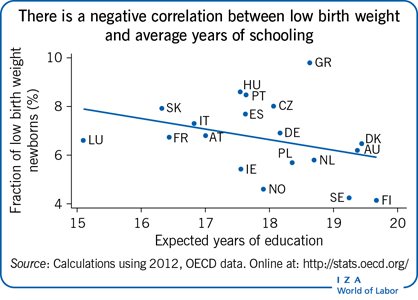

Studies linking early-childhood health to educational outcomes can be classified into two groups: those focusing on prenatal health and those focusing on early-childhood postnatal health. The literature investigating the impact of prenatal health on human capital accumulation generally follows one of two approaches. In one line of work, researchers use a proxy measure of prenatal health and examine its impact on academic achievement later in life. The majority of this work uses birth weight as a proxy of prenatal health, exploits longitudinal data, and employs twin or sibling fixed-effects strategies. Comparing two siblings born to the same mother allows researchers to account for potentially unobserved time-invariant family characteristics that may jointly determine prenatal health and child academic achievement. Results from these studies, based on data from various periods and countries, consistently show a positive association between birth weight and an array of educational outcomes, such as test scores and educational attainment.

A second line of research exploits natural experiments to analyze the impact on human capital accumulation of in-utero exposure to adverse prenatal conditions. Most of these studies employ difference-in-differences estimation strategies and use variation in intensity of exposure to compare the outcomes of cohorts exposed to the “intervention” in-utero to the outcomes of unexposed cohorts. While earlier empirical evidence on this topic focuses on extreme events, such as famines, pandemics, and natural disasters, recent evidence shows that a range of mild insults while in-utero may also have significant long-term consequences. Examples not only include mild nutritional shocks (e.g. fasting) but also environmental conditions (e.g. pollution, temperature) and family well-being (e.g. maternal mental health, domestic violence).

Research into the effects of early-childhood postnatal health on academic achievement relies mainly on cross-sectional ordinary least squares or sibling fixed-effects strategies. Some of these studies rely on adult height as a summary measure of early-childhood postnatal health, noting that height during adulthood is strongly correlated with height during early childhood (e.g. height at age five) and that height in early childhood is, in turn, affected by prenatal health, poor nutrition, and illness. Several other studies examine how the presence of specific health conditions in early childhood affect human capital accumulation later in life. These studies focus not only on the role of physical health problems (such as asthma and major injuries) but also on the role of mental health issues (such as conduct disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). The findings from this literature generally indicate that physical illness during postnatal early childhood has less of an impact on academic achievement than fetal exposure to adverse events. However, mental health conditions seem to have large and persistent effects, even after controlling for child health at birth.

There is continued interest in the research linking early-life health to long-term outcomes. The literature in this area is expanding in several ways. First, a growing number of studies rely on proxies of prenatal health other than birth weight. For example, researchers have examined the effects of gestational age on educational performance and found that being late-term (as opposed to full-term) has a positive impact on cognitive outcomes but that being premature or small-for-gestational-age has no penalty on educational performance. Recent research also uses fetal measures from ultrasounds to study effects on child health, including birth weight and height. One important finding that emerges from this work is that birth weight and height capture different aspects of the uterine environment, highlighting the difficulty of relying on a single proxy of prenatal health. To date, there are no studies linking fetal measures to educational performance.

Second, researchers are trying to shed light on the mechanisms driving the relationship between early-life health and long-term outcomes. Particular attention has been paid to the role of parental investments with some studies finding evidence of parental compensating behavior and others finding evidence for parental reinforcement (i.e. investing more in the child with higher early-life endowment). Existing evidence suggests that parents are more likely to engage in reinforcing behavior if they have low resources, highlighting the complex interaction between budget constraints and preferences.

Finally, a growing body of research is investigating the impact of intra-family health on the human capital accumulation of children. For example, researchers have shown that a disabled third-born has a larger negative impact on the second-born child's educational performance than the first-born child's outcomes, relative to the case where the third-born is not disabled. Peer effects and changes in family resources both seem to be important mechanisms behind this effect. Research also suggests that older children may impact their younger siblings’ exposure to infectious diseases early in life. For example, a recent study documents that local infectious disease outbreaks have an additional penalty on the second-born child's health during their first year of life, relative to the first-born child. Early-life infectious disease exposure also seems to have a differential impact on the educational performance of second-born children. Studies suggest that parental health shocks also affect children's school achievements. For example, researchers have found that parental hospitalizations due to cancer and acute cardiovascular disease have a significant negative impact on children's test scores. Similarly, parental psychiatric disorders seem to be associated with increased likelihood of high school dropout.

Medical care, early-childhood health, and human capital accumulation

A rich literature in economics investigates the effects of early-life access to medical care through health insurance coverage. These studies generally exploit the staggered expansion of Medicaid across US states during the 1980s and 1990s as an exogenous source of variation. While earlier studies document effects on short-term health and health care utilization, the emerging literature focuses on long-term health and educational performance. One study that focuses on individuals who gained access to Medicaid coverage in-utero and during the first year of life finds that these individuals not only have better health as adults, but they also have higher high school graduation rates. Evidence suggests that exposure to Medicaid expansions at older ages also has economically important effects on educational outcomes. Using publicly available data from the Census, the Current Population Survey, and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, one study shows that expanding health insurance coverage for low-income children leads to higher rates of high school and college completion. These findings are confirmed in a recent study using administrative data from the Internal Revenue Service, finding that greater Medicaid eligibility increases college enrolment through age 21 [1]. Recent evidence also indicates that individuals’ childhood Medicaid exposure affects the next generation's health at birth [2]. Thus, Medicaid expansions might also impact the educational outcomes of the next generation.

Previous studies have also considered the specific components of medical care, such as prenatal care. The WHO, whose guidelines recommend 12–16 prenatal care visits for pregnant women, reports that more than 98% of pregnant women in developed countries have at least one prenatal health care visit. As such, most economic studies in this area focus on the impact of the number of prenatal care visits on child health at birth. The empirical evidence from studies using randomized trials or exploiting natural experiments generally indicates that the number of prenatal care visits has little effect on birth weight. For example, a study that exploits the 1992 Port Authority Transit strike in Pennsylvania as an exogenous source of variation in the number of prenatal care visits received by low-income mothers, who mostly rely on public transportation to access prenatal care, finds no relationship between the number of prenatal care visits and birth weight. However, the results also suggest that the treatment effects may differ according to the time of the intervention, with visits lost early in the pregnancy having a negative impact on birth outcomes and visits lost late in the pregnancy having little effect. Researchers are increasingly more interested in the importance of the timing of prenatal care. A recent study exploits a Polish policy that made existing cash transfers for newborns conditional on starting prenatal care within the first ten weeks of gestation. While the study cannot document effects on prenatal care directly, the results suggest that the policy had positive effects on neonatal health and maternal health behavior (e.g. reduced drinking and smoking).

Consistent with this finding, another study finds that longer in-utero exposure to favorable prenatal conditions leads to better educational achievement [3]. The study uses the sudden immigration of Ethiopian Jews to Israel as an exogenous source of variation in the duration of higher-quality prenatal care, including the provision of micronutrient supplements (iodine, iron, folic acid) and improved prenatal medical care technologies. Comparing children who were exposed to the change in prenatal care at different gestational ages, the study finds that earlier exposure to better prenatal care results in higher educational attainment (lower grade repetition, lower dropout rates, and higher baccalaureate rates).

On postnatal medical care, there is robust evidence that early-life medical treatments provided to at-risk children have substantial effects on early-childhood health. One study investigates the impact of the length of the postpartum hospital stay on readmission rates. To address the variation in length of stay, the study exploits changes in US federal and state laws that substantially reduced early hospital discharges. The results suggest that legislation-induced increases in postpartum stays reduced hospital readmissions among those with the greatest likelihood of a readmission. Another study examines the shortening of postpartum stays in Denmark as a cost-saving measure [4]. The authors exploit cross-county variation in the implementation of this policy which mandated same-day post-birth discharge and document significant negative health effects for disadvantaged mothers. The study also finds that the policy was associated with a modest decline in the ninth grade test scores of children born to disadvantaged mothers.

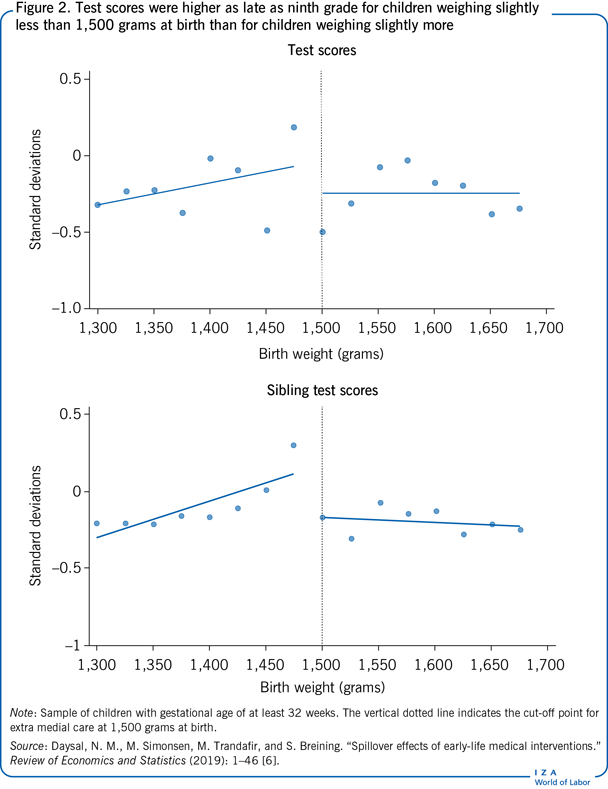

Researchers have also considered the returns to medical treatments for low birth weight children. A US study exploits the fact that medical guidelines recommend providing additional treatments to children with a very low birth weight (birth weight below 1,500 grams). Using a design that exploits changes in medical treatments across the very low birth weight threshold, the study finds that children who weighed slightly less than 1,500 grams (and who were thus eligible to receive extra medical care) were less likely to die within the first year of life than children who weighed slightly more than 1,500 grams (and were hence not eligible for extra care) (Figure 1).

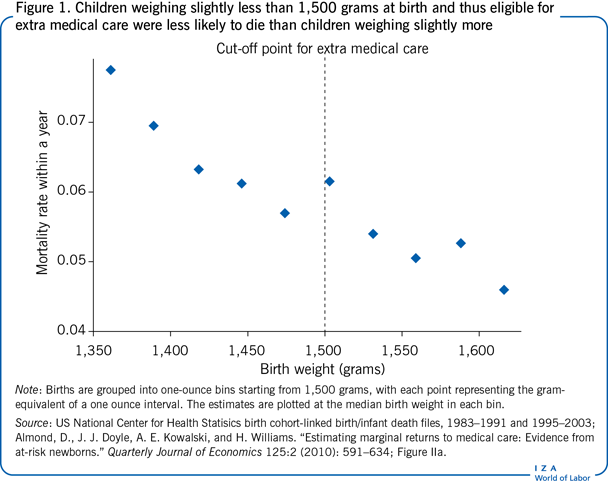

Subsequent work shows that these early-life medical treatments also have significant effects on human capital accumulation. Two recent studies employ a similar methodological design, exploiting changes in medical treatments across the very low birth weight threshold [5], [6]. Using administrative data from Chile and Norway, one study finds that children who were eligible to receive extra medical care at birth had 0.15–0.22 standard deviation higher test scores as late as tenth grade [5]. The other study uses administrative data from Denmark and confirms that children who weighed slightly less than 1,500 grams at birth (and thus were eligible to receive extra medical care) had higher ninth grade mathematics test scores than children who weighed slightly more than 1,500 grams [6]. The study also documents economically significant spillover effects on the academic achievement of siblings. The estimates suggest that siblings of children who were eligible to receive extra medical care had higher ninth grade language test scores (0.386 standard deviations higher) and mathematics scores (0.255 standard deviations) than siblings of children who were not eligible for extra medical care (Figure 2).

For low-risk children (i.e. children without known medical risk factors), however, evidence on the health impact of early-life medical care is mixed. One study investigates how length of postpartum hospital stay affects infant outcomes among low-risk mothers (i.e. women without known medical risk factors) in the US [7]. The study exploits the fact that insurance rules count the number of midnights in care when reimbursing a predetermined number of “days” in the hospital. Thus, a newborn delivered slightly after midnight has an additional night of reimbursable care compared with an infant born slightly before midnight. The study finds that while infants born just after midnight have significantly longer postpartum hospital stays than infants born just before midnight, both groups of infants have similar health outcomes, as measured by readmission and mortality rates.

Two studies focusing on low-risk newborns in the Netherlands, however, find significant health gains from higher medical care [8], [9]. In the Netherlands, maternity care is provided according to a rigorous process of risk selection based on medical history and current health status, as well as the development progress of the mother and the fetus. One of these studies investigates the impact of home births on the short-term health of low-risk newborns using a strategy that exploits the exogenous variation in distance from a mother's residence to the closest hospital with an obstetric ward [8]. The results suggest that giving birth in a hospital leads to significant reductions in infant mortality among low-risk mothers but that the results are driven mainly by the poorer segment of the Dutch population.

The second study exploits a Dutch policy rule which states that low-risk deliveries before week 37 should be supervised by physicians and later deliveries only by midwives with no physician present [9]. This rule not only changes the provider but also creates large discontinuities in the probability of receiving medical interventions only physicians are allowed to perform. The results again suggest that low-income women benefit from receiving a higher level of medical care. At this point, there is no research on the effects of early-life medical care on the human capital accumulation of low-risk children.

Public health interventions, early-childhood health, and human capital

There is robust evidence that public health policies targeting early-childhood nutritional well-being have significant benefits for health. A notable public health program of this kind is the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children in the US. The program, which covers low-income pregnant and lactating women and children up to age five, provides monthly food checks or electronic benefit transfer cards that participants can use to buy nutritious foods. In addition, participants receive nutrition education and breastfeeding support. A large literature in economics, using a variety of estimation techniques, shows that the program improves infant health at birth, such as birth weight. However, there is almost no evidence on the longer-term health effects of the program and virtually no studies on its impact on human capital accumulation.

There are, however, other studies that document educational benefits for public policies with a nutritional component. For example, one study examines the long-term effects of in-utero alcohol exposure [10]. The study exploits a policy in place in certain regions of Sweden that temporarily allowed individuals younger than 21 to drink strong beer. Children born to women who resided in these regions while pregnant and under 21 at the time the policy was in effect had significantly lower educational attainment, as well as lower cognitive and non-cognitive ability.

Public health interventions targeting smoking behavior also document long-lasting effects on child health and development. One study examines a 2004 law change in Norway that imposed smoking bans in bars and restaurants. Focusing on mothers who worked in restaurants and bars during this period, the study finds that mothers exposed to the smoking ban were less likely to have premature or very low birth weight children. Another study investigates the effects of in-utero exposure to smoking using a strategy that exploits variation in state cigarette taxes [11]. The results suggest that state cigarette excise tax leads to significant reductions in sick days from school.

Finally, there is some emerging evidence pointing to human capital benefits for home visiting programs, which are highly popular in developed countries. While the specifics of the programs vary, they generally provide education on parenting skills, infant safety, health, nutrition, and child development. This research generally uses the introduction of home visiting programs as a natural experiment. The findings indicate that home visiting programs provided by qualified nurses improve both short-term and long-term health. Some recent work investigates the impact of well-child visits (visits providing physical examination as well as information on child development, safety, health, and nutrition) on educational outcomes. The study uses a strategy that exploits the differential timing of rollout across Norwegian municipalities by comparing the change in outcomes between municipalities with the program and those without it [12]. It finds that access to well-child visits during the first year of life increases completed years of schooling by 0.12 to 0.18 years. More recent studies aim to examine the effects of the intensity and the timing of home visiting programs as well as the pathways through which they might impact child health and development.

One study examines the effect of missing a nurse visit, exploiting a Danish nurse strike as an exogenous source of variation. The results suggest that missing an early visit has negative effects on child and maternal health, as proxied by increased health care contacts in the future. Another study investigates the effects of an information campaign in Denmark implemented through the home visiting program. The information campaign provided knowledge on safe infant sleeping positions in order to reduce sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The study finds that the information campaign led to economically large reductions in infant mortality.

Limitations and gaps

There are several limitations and gaps in the work evaluating the impact of early-life medical care and policy interventions. The evidence on the effects of prenatal care comes primarily from studies focused on the number of prenatal visits, and these studies investigate mainly short-term health outcomes. However, because prenatal medical care coverage in developed countries is nearly universal, the timing and quality of prenatal care may matter more than its quantity. In addition, prenatal care may improve outcomes that cannot be captured with readily available proxies of health at birth, such as birth weight. There is currently no evidence on whether and how prenatal care affects educational performance. More research is needed to fully assess the effects of prenatal care, especially with respect to differences in efficacy of treatments across population groups.

There is robust evidence on the benefits of early-life medical treatment for high-risk children. While these studies have high internal validity (confidence that a causal study has been well done), their results are generally applicable only to “compliers,” individuals whose receipt of medical treatments is determined by the particular so-called instrumental variable exploited by the study. The marginal individual (those who receive medical treatments because of the instrument) in this case may not be representative of the general population. A careful understanding of the external validity (generalizability) of these results is needed when crafting related public policies.

Further research is also needed to reconcile the mixed evidence on the health returns to early-life medical interventions for low-risk individuals. Why do certain types of medical care have higher returns than others? Do medical interventions provide the same health benefits across all subpopulations? What is the role of risk selection in explaining the different findings? Is risk selection always possible? In addition, research is needed to investigate the impact of these interventions on long-term health. Even if there are no effects on short-term mortality, there may be effects on health that become more apparent in the long term. Similarly, more information is needed on the human capital effects of treatments that conclusively provide health benefits.

While there is abundant evidence on the short-term health benefits of the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children in the US, there is only limited information on how the program affects postnatal early-childhood health and virtually no information on its impact on longer-term academic achievement.

Similarly, the literature on nurse home visiting programs mainly focuses on the extensive margin. While a number of recent works in progress consider the health effects of the intensity or the timing of these programs, none of these investigate effects on educational outcomes. In order to optimally design home visiting programs more research should be conducted on different elements of care (e.g. quality, timing).

Another area where more work is needed is on the impact of medical care and public health interventions targeting parental health (especially during the early life of their children) on the outcomes of children. An emerging literature links poor parental health to worse academic achievement of children. Little is known, however, about whether these adverse effects can be overcome by medical treatments or public health interventions.

More research is also needed to understand the causal pathways leading to the returns to medical care and public interventions, as well as potential externalities generated by the interventions. The net effect of any intervention or treatment depends in part on how parents respond to it. For example, to the extent that parents compensate for differences in early-life health status of siblings, any health improvement due to medical treatments may be offset by reduced parental investments. There is a large body of research on how parents change the allocation of resources within the household in response to these “endowments at birth.” Results from this literature are mixed, supporting both compensating as well as reinforcing behavior depending on the context. However, there is no study in the context of a developed country that specifically considers the impact of early-life interventions on parental behavior.

Finally, evidence is needed on how medical care and public health interventions interact to shape child health and human capital accumulation. Existing research points to the separate importance of different types of medical care and public health policies. Understanding whether these interventions act as complements or substitutes, and whether this differs across populations or child outcomes, is vital for crafting effective programs.

Summary and policy advice

The evidence on early-childhood interventions indicates that various medical treatments and public health programs (especially those for high-risk children) produce not only health benefits but also improvements in long-term educational outcomes. These long-term effects should be kept in mind when considering the cost-effectiveness of any given intervention.

Not all interventions are universally beneficial, however. There is mixed evidence on the returns to early-childhood interventions for low-risk children, implying a potential for cost-savings. Policymakers should take this into account when crafting policies, particularly those targeting large populations, where there may be more scope for differences in treatment efficacy.

Finally, results also suggest that the flat part of the curve for some medical treatments has been hit. For example, it may be more productive to shift the policy discussion from increasing the number of prenatal or postnatal nurse home visits to improving the timing and quality of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the discussion on the spillover of early-life interventions onto family members, not just siblings, shifts the policy discussion to the effects of the timing and quality of care, updates Figure 2, and fully revises the reference lists.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© N. Meltem Daysal and Jonas Cuzulan Hirani