Elevator pitch

Public debate on immigration focuses on its effects on wages and employment, yet the discussion typically fails to consider the effects of immigration on working conditions that affect workers’ health. There is growing evidence that immigrants are more likely than natives to work in risky jobs. Recent studies show that as immigration rises, native workers are able to work in less demanding jobs. Such market adjustments lead to a reduction in native occupational risk and thus an improvement in native health.

Key findings

Pros

Immigration can allow natives to work in jobs that involve better schedules, lower rates of injury and fatality, and which are less physically intensive.

There is evidence of positive effects on native workers’ health and subjective well-being after immigrants fill lower-skill jobs.

Improvements in working conditions and health related to increased shares of immigrant workers are concentrated among the most vulnerable native individuals, i.e. low-skilled, blue-collar workers.

Evidence suggests immigrants are still likely to work in safer conditions than in their countries of origin.

Cons

The self-selection of immigrants into riskier jobs contributes to deterioration in their own health.

Immigration increases safety-related costs due to language barriers and different standards of job safety between home and host country.

If immigrants perceive their jobs more positively than natives, they may take excessive risks.

There is some evidence of short-term negative effects on native low-skilled wages and employment in relation to increased shares of immigrant workers.

Author's main message

While public debate usually focuses on the effects of immigration on native workers’ wages and employment issues, recent evidence suggests that immigration may also have non-trivial effects on other working conditions that are known to affect work-related health risk and thus individual health and well-being. More open immigration policies that allow for a balanced entry of immigrants of different education and skill levels may therefore have positive effects on productivity, with no detrimental effects on wages. They are also likely to have positive effects on job quality and the health of native workers.

Motivation

Immigration is often blamed for bringing down wages and decreasing job opportunities for native workers, as well as for increasing health care costs and the burden on taxpayers. The fear of negative effects on native workers and governments’ public finances attracts the attention of media and policymakers, particularly during recessions. In contrast, a popular argument in favor of immigration is that immigrants accept jobs that native workers would prefer not to. Immigration can also address short-term skill shortages and enhance complementarities in production associated with workers of differing skill levels. Empirical evidence shows that immigrants in developed countries are typically younger and healthier than their counterpart population (the “healthy immigrant effect”) and are therefore less likely to use health care services and more likely to accept high-risk jobs. At the same time, recent studies have shown that local economies rapidly adjust to immigrant inflows and that complementarities in production functions and task-specialization may explain the lack of evidence of a negative effect of immigration on native average wages and employment opportunities.

As both public and academic debates have so far focused mainly on the effects of immigration on wages and employment, very little is known about how immigration affects other important labor market characteristics, such as the occupational risk, physical intensity, and work schedule associated with a given job. This article presents recent evidence on the effects of immigration on native workers’ health, as well as on occupational characteristics that are known to significantly affect individual health and well-being.

Discussion of pros and cons

Immigration and task-specialization

Economists have been interested in understanding the effects of immigration on the labor market for many years. Most studies have found little or no evidence of negative effects of immigration on native workers’ wages and employment opportunities. While some studies show evidence of a negative effect on the wages of less-educated native workers, most do not find significant differences between the effects on high- and low-skilled workers. Instead, there is evidence that newly arrived immigrants have significant negative effects on the wages of earlier immigrant cohorts.

These findings have long puzzled researchers, as they are at odds with the prediction of the canonical labor “supply and demand” model, which would predict a negative impact of immigration on wages and employment prospects of native workers. While a natural concern is that local labor markets may absorb the immigration shock due to the internal mobility of native workers, most studies have found little evidence of immigration effects on native workers’ migration flows.

More recent studies have shown that immigration may have positive effects on productivity by stimulating specialization [1], [2], [3]. Native workers may be induced to specialize in complex tasks as a response to immigration and because of the complementarities with manual tasks for which immigrants may have a comparative advantage. In particular, these studies suggest that low-skilled native and immigrant workers specialize in differentiated production tasks. Because some immigrants have imperfect communication skills, but have physical skills that are equivalent to (or in some cases better than) their native counterparts, they have a comparative advantage in performing jobs that require manual tasks, while low-skilled native workers have an advantage in communication-intensive jobs.

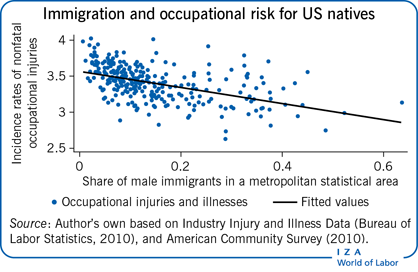

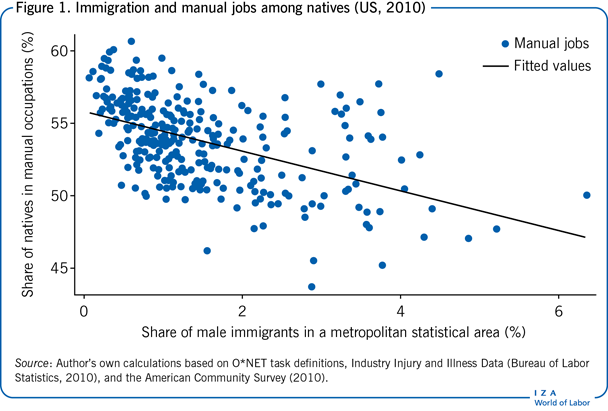

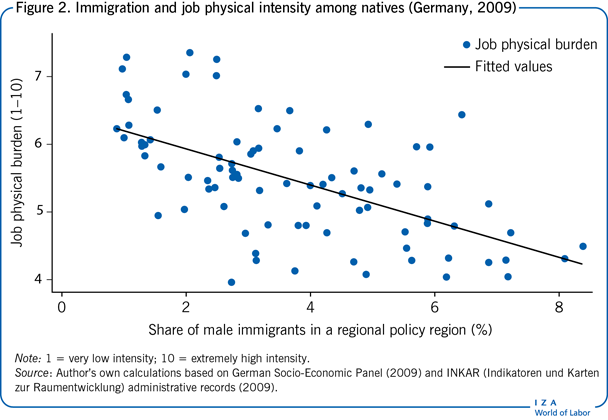

Task complementarities and firms’ capacity to adjust their production function as a response to the increased labor supply can explain the lack of detrimental effects on wages and employment. A number of recent studies suggest that this adjustment process may improve the job quality of native workers and have non-negligible effects on individual health and well-being [4], [5]. There is also evidence that immigration pushes native workers toward more communication-intensive jobs and reduces the physical burden associated with certain occupations (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Furthermore, immigration decreases the likelihood of native workers working late hours and non-standard shifts [8], [9].

Thus, if on the one hand exposure to competition in the labor market may have detrimental effects on the health of the more exposed native workers (i.e. low-skilled natives), on the other hand, an inflow of immigrant workers may have positive effects on the health of native workers by reducing their occupational risk and improving working conditions.

Immigration and occupational risk of immigrants

Recent literature provides evidence that immigrants are more likely than natives to work in risky jobs [10]. One group of studies used information on industry or occupational sector to measure occupational risk based on the average fatality or injury rate. These studies conclude that immigrants are more likely to work in occupations and industries with high fatality and injury rates. Similar findings have been observed across advanced economies, including Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9].

It is important to note that earlier studies analyzing older US data find little evidence that immigrants work in riskier jobs than natives. The divergent results are explained by differences in the methods of measuring risk, as well as by the different cohorts of immigrants analyzed. In particular, it has been argued that the increase in immigrants’ job-related risk in the US may be explained by a decline in average human capital among immigrants. It can also be explained by the fact that immigrants have been crowded into riskier jobs because of the increase in the immigrant population over time. Some studies in other countries (i.e. Spain) have also directly investigated whether immigrants are more likely to be injured or killed in the workplace by exploiting individual medical records [6]. Overall, these studies confirm a higher incidence of fatalities and injuries among immigrants, with a few exceptions finding non-significant differences between natives and immigrants in Finland and Sweden [11]. Similarly, evidence shows that immigrants are more likely than natives to work late and to work non-standard hours.

Working conditions and health

There is growing evidence that working conditions can have long-lasting effects on workers’ physical health and cognitive abilities. Workers employed in physically demanding jobs are at a significantly higher risk of injury and experience more rapid aging compared to workers in less physically demanding jobs. Similarly, working irregular shifts or night schedules increases the risk of negative health outcomes and adversely affects individual and family well-being.

Non-standard work schedules reduce the amount of time spent with family and friends, which affects the consumption of relational goods. This has important consequences for marital stability, children's well-being, and, more generally, individual life satisfaction. Findings show that working non-standard hours increases the risk of obesity, ischemic heart disease, and breast cancer. More generally, inadequate working conditions affect the likelihood of chronic fatigue, anxiety, and depression.

It is worth noting that job disamenity—the unpleasant disadvantages or drawbacks associated with certain roles or working conditions (i.e. working at night)—is not distributed evenly among workers. Recent US data reveal that the majority of workers with non-standard schedules have earnings that are below the median of the typical US worker. It could be argued that individuals choose these jobs because of the compensating wage differential—the additional amount of income required to motivate them to accept the job—associated with poor working conditions. However, there is little empirical evidence to support the existence of risk premiums. Overall, research indicates that immigrants can earn risk premiums that are similar to those of natives, but some groups (e.g. Mexicans in the US) earn smaller or no risk premiums. The wage premium for irregular shifts is also relatively small. In the US, only a small fraction of workers report working non-standard hours because of the compensating wage differential. This evidence suggests that job disamenity is often a result of limited labor market opportunities. In view of these considerations, there is now an increasing focus on improving workers’ awareness of the risks associated with particular working conditions, while improving the job quality of immigrants has become an important policy issue.

The effect of immigration on native health

There is growing evidence that immigrants are more likely to hold risky jobs than natives and that physically intensive occupations have negative effects on individual health. However, very few studies have investigated the causal effects of immigration on the job quality of natives (e.g. working schedules, physical burden, and risk of injury). Evidence drawn from firm-level data collected in the 1970s in Germany shows that a higher share of foreign guest workers in a company is associated with fewer severe accidents among the company's native workers [12].

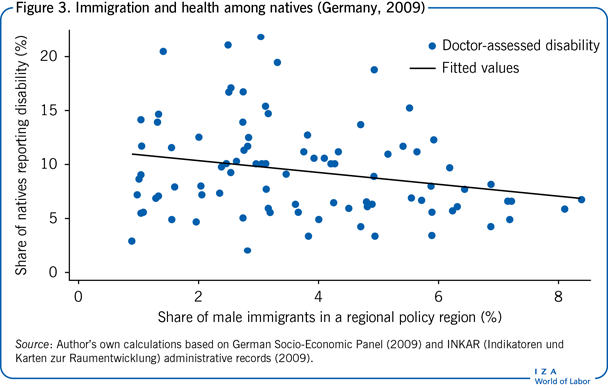

Consistent with these earlier findings, new research using longitudinal data from Germany shows that an increase in the share of immigrants living in a local labor market decreases the likelihood that natives will report doctor-assessed disability and, more generally, has a positive impact on native health (Figure 3) [4]. One of the major challenges of the spatial correlation approach is that the location of immigrants across different areas may be endogenous. Natives may respond to the wage impact of immigration on a local area by moving to other areas, and immigrants may cluster in areas with better economic conditions. However, in this case, the longitudinal nature of the data allows for following individuals over time wherever they move, thus internalizing the spillover effects that may be induced by native mobility, which would typically bias area studies.

Merging the German socio-economic data with local labor market characteristics, the study shows that a 1% increase in immigration share reduces the probability of reporting a doctor-assessed disability by roughly 10% with respect to the mean. The reduction in the average native occupational risk becomes larger in absolute value when accounting for potential endogeneity, controlling for local labor market economic trends, and when using a so-called instrumental variable approach. Furthermore, the impact of immigration on native workers’ health is concentrated among low-skilled and blue-collar workers. This result is consistent with the idea that low-skilled natives and low-skilled immigrants are imperfect substitutes and that the increase in the number of low-skilled immigrants may allow natives to work in less physically demanding tasks. The direction of the effect of immigration on health is confirmed when using more subjective health outcomes, such as health limitations and self-assessed health status, rather than doctor-assessed disability. Furthermore, immigration reduces the rate of native workers reporting concerns about their health status as well as work accidents for the years in which this information is available.

Following a similar approach, some research has found evidence of a positive effect of immigration on life satisfaction, suggesting that native Germans obtain welfare gains as immigration increases [13]. Similarly, the number of workplace accidents suffered by Spanish workers dropped by 7% between 2003 and 2009 as a result of a large inflow of immigrants. Conversely, there is little evidence of negative effects stemming from the immigrant outflow that Spain experienced after 2009. The immigration effect on subjective well-being is particularly strong in those regions in which immigrants are intermediately assimilated. These studies point to positive effects of immigration on dimensions that have been so far understudied. They also help to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of immigration on native workers’ welfare. However, more research is needed in order to clearly identify the mechanisms underlying the relationships between immigration, health, and individual well-being.

Consistent with that observed in other countries, recent studies analyzing US data document a similar effect of immigration on the likelihood of natives working in safer jobs, with fewer injuries and reduced compensation benefit claims from workers [7]. In particular, in the US, the presence of low-skilled immigrants has been associated with improvements in the health of low-skilled natives.

The effects of immigration on native workers’ health varies along the skill distribution. Evidence from the UK suggests that between 2003 and 2013 immigration reduced the occupational risk of UK-born workers with medium levels of education, but had no significant effect on those with low levels [5].

The effect of immigration on working conditions

The ability to identify the channels through which immigration may affect health has so far been limited by the lack of company-level data that includes precise information on workers’ age, health, the physical intensity of their jobs, and whether they have sustained injuries. It is worth noting that current studies focus on occupational risk and job types, rather than on the conditions of jobs themselves. There is also evidence that immigration reduces the average workload of native workers and pushes them toward more “communication-intensive” jobs and more standard schedules [1], [2], [3], [4], [6], [7], [8], [9].

While immigration is negatively correlated with native workers’ physical burden, its average effect is not precisely estimated [4]. There is, instead, evidence to show that when immigration increases, blue-collar workers experience a significant reduction in their average physical burden and are more likely to switch to less physically demanding jobs. However, the estimated effects are generally small and can only partially account for the positive effect of immigration on health. This may be explained by the fact that the studies analyzing occupational risk and job physical intensity rely largely on variation across occupation and ignore “intra-occupation” changes. Consistent with this conjecture, survey data show that occupational risk captures only a small part of the total effect of immigration on workers’ physical burden. Furthermore, evidence based on firm-level data suggests that new immigrants are primarily employed in risky activities and that as more immigrants are available to take riskier jobs in a firm, native workers have the opportunity to be promoted to safer tasks [12].

Overall, the analysis of firm-level data and perceived physical burden implies that immigration may have important “intra-occupation” effects, stimulating task-specialization and internal reallocation of risks. Therefore, current studies may substantially underestimate the effects of immigration on native workers’ physical burden, thereby predicting a smaller reduction than that observed when including task changes within a given occupation.

As discussed above, work schedules have significant effects on workers’ health and well-being. Immigrants are more likely than natives to hold irregular shifts and to work non-standard hours. These shifts are less communication-intensive and immigrants may have lower relational costs as a result of not being synchronized with most other people, particularly if they immigrated without family. Again, because of these complementarities in the production function, one may expect positive effects on native workers’ schedules.

A study using Italian labor force data shows that doubling the share of immigrants in a province results in a reduction of 2−4% in the likelihood of natives working non-standard hours, depending on the different specifications of the model. Since an average 28% of natives reported working “non-standard hours” shifts, the coefficient implies a reduction of 7−15% of the share of natives working non-standard hours [9]. These results are driven by workers in blue-collar jobs and non-financial services, while there is no evidence of significant effects in the public and financial sectors.

US data reveal similar findings [8]. Nearly 5.5 million foreign-born workers work in jobs with non-standard hours, accounting for more than 8% of non-regular hours. In sectors such as manufacturing, where stopping or idling machines incurs large costs, non-standard shift workers are crucial, yet there is growing evidence to suggest that firms in the US have trouble staffing overnight shifts (e.g. manufacturing, growers of fresh produce). Difficulties in filling these positions may affect overall expansion and the ability of firms to add jobs at all hours. In many industries, almost half of workers work non-standard shifts. As immigrants have a comparative advantage in working non-standard shifts, immigration may allow firms relying on flexible workforces to remain competitive.

A recent study finds that a 10 percentage point increase in the fraction of foreign workers in a local labor market leads to a 0.51–0.77 percentage point decrease in the probability of natives working at night, and a 0.73 percentage point relative increase in native daytime wages [14]. These changes are driven by a movement of native workers into occupations that specialize in daytime employment, moving away from agriculture, mining, construction, and manufacturing into wholesale and retail trade, finance, and services. The strongest effects are found among low-skilled workers, consistent with the hypothesis that low-skilled natives would be the closest substitutes to immigrant workers.

Given that most of these studies rely on cross-sectional data and considering the limited information available on compensating wage differentials, health outcomes, and job satisfaction, it cannot be concluded that the overall improvement in working schedules represents a general welfare improvement for native workers. Nonetheless, the apparent negative effects of shift work and late hours on health and well-being suggest that policymakers should not neglect the impact of immigration on natives’ schedules when evaluating immigration policies.

The effect of working conditions on immigrants

The other side of the story is that immigrants who self-select into more physically demanding jobs face steeper aging profiles. Evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) shows that immigrant men, upon their arrival, have a much lower incidence of doctor-assessed disability than native men, but that their health quite rapidly converges to native men's health over approximately 15 years [4]. The annual rate of health depreciation associated with time spent in Germany is significantly lower among men who were employed in less strenuous occupations in the previous year (i.e. jobs with physical intensity lower than the median).

As discussed previously, there is also evidence that immigrants may misperceive risk because they are less familiar with their new environment, face language barriers, and, on average, have lower socio-economic status. For the same reasons, companies may find it more costly to invest in health and safety training in firms when the number of immigrant workers increases. A concern for policymakers, therefore, is that immigrants may not be aware of the long-lasting consequences of their working conditions. They may also take excessive risks on the job and may not compensate for these risks with adequate care. This could also have consequential effects on health care costs. Yet, it is worth noting that for many immigrants, risk of injury in the host country is lower than that they would have faced working in the same occupation in their country of origin. Indeed, evidence from the EU Labor Force Survey suggests immigrants on average face significantly lower occupational risk than in their countries of origin, suggesting a “pareto-improvement”—i.e. at least one person is better off as a result, without anyone else being made worse off—in working conditions [5].

Limitations and gaps

In general, research on the impact of immigration has focused on its effects on employment, wages, and consumption prices. It has only recently begun to analyze the effects of immigration on native workers’ health and well-being. While initial studies suggest that immigration increases average job quality and has positive effects on health, life satisfaction, and well-being, very little is known about the mechanisms underlying these relationships or the heterogeneity of the effect in the population. Furthermore, the analysis has been limited by the availability of data containing detailed information on occupational characteristics and health. In particular, research to date indicates that native workers move into jobs that involve lower risks and have better working schedules. The length of time that workers are exposed to adverse risks in employment is also likely to play an important role in explaining the relationship between immigration and the health of native-born workers. While some of the studies mentioned above discuss the dynamics of these effects, future research utilizing longer panel data may shed further light on their respective timing.

Existing research does not analyze directly whether immigration inflows have led to changes in actual working conditions. Indeed, due to the lack of information on individual and firm-level working conditions, most studies rely on occupation-level differences. Much more could be learned by exploiting firm-level data and longer longitudinal data series. In addition, further research should explore different contexts. For example, very little is known about the relationship between immigration and occupational risk in developing countries, despite the fact that south−south migration exceeds south−north migration.

Finally, future research should shed further light on the mechanisms underlying the relationship between immigration and the health of native and immigrant workers. The use of longitudinal data and instrumental variable strategies based on “push” rather than “pull” factors may further contribute to the identification of a causal link between immigration, working conditions, and health.

Summary and policy advice

Empirical evidence suggests that immigrants are more likely than natives to hold risky jobs. In particular, immigrants are more likely to work in manually intensive and more physically demanding jobs compared to their native counterparts. These jobs are characterized by higher injury and fatality rates, and there is growing evidence to suggest that they have negative effects on workers’ health.

There is also evidence that immigration may improve the working conditions of native workers by reducing the average number of hours worked and by reducing the physical intensity of blue-collar jobs. Indeed, several studies find evidence that immigration reduces natives’ occupational risk. These improvements in working conditions may have significant effects on the health of the native population. Overall, the evidence suggests that policymakers should not disregard the effects of immigration on non-monetary working conditions. Policy should thus focus more on improving immigrant workers’ awareness of the risks associated with particular working conditions and on improving the job quality of immigrants. As new and healthy immigrants may misperceive the risks associated with particular working conditions and take excessive risks, providing information and access to care to those immigrants at higher risk could reduce both the negative effects on their health and the associated costs for the health care system [4]. Yet, it should be noted that current evidence suggests that most immigrants end up facing lower risks than they would in the same jobs in their countries of origin.

Finally, evidence supports the view that immigration reduces the average workload of natives and allows native workers to work toward more communication-intensive jobs and more standard schedules. Given the negative effects of shift work and late hours on health and well-being, policymakers should not neglect the impact of immigration on natives’ work schedules when evaluating immigration policies.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the research, including evidence that although foreign workers take on riskier jobs in their host countries, those jobs are still safer than in their home countries; new “Key references” are also added [4], [5], [6], [7], [9], [13], [14].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Osea Giuntella