Elevator pitch

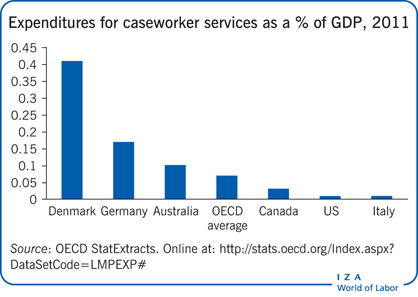

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries spend, on average, an equivalent of 0.4% of their gross domestic product on active and passive labor market policies. This is a non-negligible sum, especially in times of strained government budgets. Meetings with case workers—who can provide advice and information on what jobs to look for, and how to search, and give moral support, as well as monitor search intensity—are a simple and effective option for policymakers to help the unemployed find work.

Key findings

Pros

A case-worker-based approach is a simple and less costly policy option for increasing job-finding rates.

Meetings can be scaled up or down to accommodate the upturns and downturns of the business cycle.

Meetings with case workers appear to be associated with longer-term job stability for the reemployed.

Because there are no lock-in effects, meetings can be an effective tool early in the unemployment period, when a worker’s chances of being rehired are at their highest.

Cons

Meetings tend to help only the most employable workers (whose skills and abilities are demanded by the local labor market), while not helping less desirable workers.

If there are fewer jobs than job-seekers, meetings may help some workers get the available jobs at the expense of other seekers.

Economists do not fully understand how and why meetings are beneficial to individual job seekers.

Author's main message

Meetings between the unemployed and case workers are an inexpensive policy option. They can easily be scaled up or down, their content can easily be varied, and they are an effective tool during the early phases of unemployment. A modest shift in emphasis on traditional activation tools toward a more intensive use of case workers’ own competencies can simultaneously reduce unemployment and the costs of active labor market policies.

Motivation

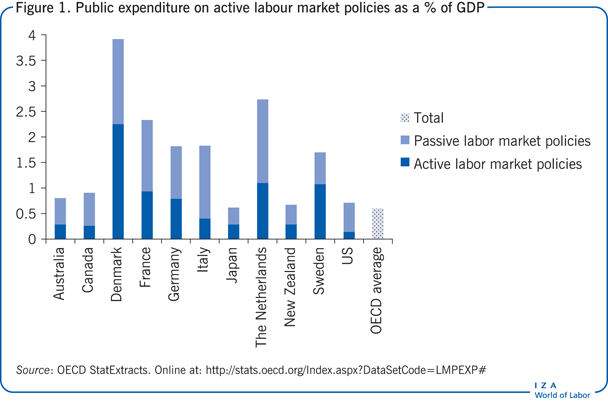

In many countries, government expenditures on passive and active labor market policies are non-negligible. According to OECD data, Denmark spent 2.3% of its GDP in 2011 on active labor market policies (ALMPs) alone. The corresponding figure for Germany was 0.8%, for Sweden 1.1%, and for the OECD as a whole 0.6% (see Figure 1).

ALMPs are seen by many policymakers as a key component in fighting high unemployment rates, especially when it comes to ensuring effective job search and a swift return to employment for unemployed workers, as well as preventing long-term unemployment, marginalization, and social exclusion. For these reasons, ALMPs played a crucial role in many countries’ strategies for responding to the economic crisis of the late 2000s and preventing long-term effects on structural unemployment rates or even labor market participation rates.

Traditional tools in the ALMP toolbox are:

classroom training;

vocational training in firms;

counseling;

job search assistance courses;

employment subsidies; and

public temporary job creation.

However, according to several reviews, traditional activation policies often have only a limited effect, especially when their costs are taken into consideration [1], [2], [3]. (It should be noted, however, that studies with a longer time horizon tend to find more positive effects for activation policies.) Training courses in particular are quite expensive. For example, in Denmark almost half of the budget for activation policies supports training courses and education for unemployed workers.

Hence, ALMPs are expensive and not very effective at getting the unemployed back to work. Moreover, the supply of activation is difficult to adjust to accommodate business cycle changes. For example, when unemployment goes up, the need for training courses in classrooms and firms increases as well, but supply is difficult to increase overnight. This is especially true for training in firms, which appears to be the most effective instrument. Furthermore, firms may be even more reluctant to take on trainees in a depressed labor market. (Firms often use training schemes to screen new workers, but it makes no sense to bother screening when you are not hiring.)

Moreover, it is difficult to target specific types of training at different types of workers in quickly changing economic conditions. This is probably one of the reasons estimates of the effect of classroom training for the unemployed vary so much.

Finally, activation programs have well-documented lock-in effects. Because job-finding rates are lower while workers are participating in activation programs, the programs do not present policymakers with a strong option for intervening during the early phases of an unemployment spell, when the probability of a worker finding a job is high relative to later during unemployment, leading to considerable deadweight loss. Yet early intervention is exactly what is needed to prevent long-term unemployment. Thus, a flexible and effective instrument—without such lock-in effects—is vitally important.

Fortunately, policymakers already have a powerful tool in their toolbox—one that is, however, often overlooked, because it is used mostly for administrative purposes. Furthermore, this tool has many of the desirable qualities that more traditional activation instruments lack. This tool is, of course, meetings between unemployed workers and their case workers at the local public employment service (PES).

This paper will make the case for a greater reliance on meetings and for shifting ALMP away from traditional activation toward a case-worker-based approach. Such a policy shift has the potential not only to lower the overall costs of countries’ ALMPs, but also simultaneously lower (structural) unemployment. Moreover, the instrument itself is so simple and inexpensive that changes in its use can be easily evaluated and may thus induce further effectivization down the road.

Discussion of pros and cons

What happens during meetings between job-seekers and case workers?

In many countries, when a worker registers as unemployed, he is required to meet with a case worker at the local PES. The purpose of the meeting is to establish the worker’s eligibility for income transfers, to advise him on rules and regulations, and to provide information or job search assistance. Most European countries have additional requirements for how frequently workers should meet with their case workers, ranging from a few weeks to almost a year between meetings. In Denmark, the first meeting between the worker and his or her case worker must take place within the first three months of unemployment, with subsequent meetings occurring at least every three months.

Several issues may be discussed at these meetings.

Most newly unemployed workers have never been unemployed before, or have been so no more than a few times. Advice on how to conduct an effective job search is therefore likely to be very useful information for the newly unemployed. For example, the case worker may provide advice on which search channels are most effective (for example, family and friends, informal contacts, the internet, job banks, newspaper ads, knocking on doors of companies, consulting local union representatives), search requirements, how to write a résumé, and how to prepare for a job interview.

Many unemployed workers have an unrealistically high expectation as to what sort of wage to expect when conducting a job search. Thus, a crucial role of case workers is to make workers aware that they may have to accept a decrease in wages relative to their previous job, since some of their firm-specific competencies from the previous job may not be so valuable in a new job.

When workers (especially young workers) have sent off several applications unsuccessfully, they will need moral support and will benefit from having someone to inspire them, give them new ideas, and convince them to keep up the search and not become discouraged. Discouragement is the first step of a worker’s descent into marginalization and social exclusion.

Such meetings can be used to test the availability of unemployed workers for employment (and, therefore, their eligibility for unemployment benefits, which are typically conditional on an active job search and a willingness to take a job). The meetings can be used to determine whether unemployed workers are meeting specified job search requirements and to issue sanctions in the case of non-compliance.

Case workers may also have information on specific job openings. In such instances, they can directly provide this information to an unemployed worker and thus engage directly in the match-making process of the labor market.

These meetings can be used for assessing and discussing the qualifications of the unemployed and whether they have the skills and abilities demanded by the local labor market.

What happens after meetings? Perceived direct and indirect effects

Meeting with a case worker may lead to more job search—and especially to more effective searching—for several reasons. First, as mentioned above, the unemployed are typically not experts at job search. If they were, they probably would not be unemployed (for very long). Moreover, talking down their reservation wages to a realistic level might improve the likelihood that workers will accept the jobs they are in fact offered. Of course, if case workers can provide concrete information about vacant positions, that too would lead to more effective job search.

The moral support provided at these meetings also contributes to maintaining job search intensity for those who might otherwise react to several rejections by reducing their search activities (or by stopping to search altogether). After all, how to better avoid rejection than by not searching?

Even the search requirement might lead to more job search—although not necessarily improved search—if it causes workers to shift from (more effective) informal search (for example, family and friends) toward (less effective) formal job search (such as reacting to posted vacancies). Failure to live up to search requirements or other eligibility conditions may also result in sanctions, which have been documented in the literature as having large effects on subsequent outcomes. For instance, while individuals who have received a sanction tend to find jobs much faster, they also tend to find jobs that pay lower wages and have lower job stability.

But even though the evidence clearly shows that meetings tend to improve job search activities and lead to increases in job-finding rates, this still might only lead to a reshuffling of who gets the jobs. This can occur when the labor market is like a game of “musical chairs”: There are fewer jobs available than people who want them. In this case, the workers who attend the meetings may be filling the available jobs at the expense of other unemployed workers.

However, improved search might also lead first to reduced vacancy duration, as firms are now faced with more active and more effective job-seekers. Hence, firms should find it easier to fill vacant positions. This alone could lead to an increase in overall employment, as an increasing fraction of all potential jobs (filled jobs plus vacancies) are now filled. (Of course, if there are already a lot of seekers relative to the number of vacant positions, as in a depressed labor market, more search might instead lead to congestion effects and an increase in firms’ costs in screening applications. In such a case the effect might be to increase vacancy durations.)

Moreover, as firms find that filling a vacancy is easier, they may be more inclined to open new vacancies, once again leading to an increase in overall employment and thus to lower unemployment (unless participation rates are also affected). Finally, improved search could have an effect on the equilibrium wage level if it induces an increase in the effective labor supply.

Thus, while meetings can have beneficial effects at the individual level, the macro-level effects can be positive or negative depending on circumstances.

Evidence: International literature

Meetings between case workers and unemployed workers can affect behavior even before the meeting takes place (for example, if individuals search more in order to avoid a sanction) and afterwards (for example, counseling, job search assistance, moral support).

In a selective review of 37 studies on the effects of meetings and case workers on the outcomes of the unemployed, researchers have noted that most of the studies (30) find positive effects for the meetings (or aspects of the meetings) between case workers and clients, while the remaining seven find no effect [4]. One study noted a significant increase in a secondary outcome measure (the exit rate to sickness benefits), but that was the only negative effect noted throughout the survey.

A few examples from this review: One study, based on a randomized experiment in Sweden, shows that an invitation to a meeting, with the stated aim of monitoring search activity and assisting with more effective job search, causes an increase in the transition rate to employment of 46%—even before the meeting takes place. Another study, based on a randomized experiment in the US, finds similar effects. When it comes to ex post effects, the tendency in the literature is that meetings with a counseling component tend to work better than meetings with more of an emphasis on the monitoring component (although the latter also show mostly positive effects). This is the case, for instance, in an analysis of a French labor market reform that increased counseling without altering the amount of monitoring. The researchers found that programs for more employable workers speed up their job-finding and lead to longer employment duration for all workers. Similar outcomes were associated with the UK’s ReStart program.

As for monitoring, one study—which conducted a randomized experiment in Rotterdam—finds that, while workers switch from informal to formal search channels, there are no significant effects on the transition rates from unemployment to employment. In another study, which varied the number of meetings (by notifying participants that some meetings had to be cancelled because of renovation work in the public employment office), researchers found that exit rates out of unemployment are higher when meetings are held than when they are cancelled.

Other studies find a correlation between increases in job center staffing and the local unemployment rate, that the characteristics and strategies of case workers matter, and that sanctions are very effective.

Recent evidence from Denmark

The effectiveness of ALMPs in Denmark has been tested through the systematic use of randomized experiments. The first, Quickly Back to Work (QBW1), was conducted in 2005 and 2006, and targeted newly unemployed workers who were eligible for unemployment insurance benefits. It consisted of early and intensive job search assistance in the form of a course, a sequence of weekly or twice-monthly meetings (beginning after one month of unemployment), and early activation (after four months). The result was a dramatic increase in job finding rates by 20–30%. However, it is unclear whether the counseling or activation components were more significant (although most studies point to a combination) [5], [6].

In 2008, a second set of experiments was conducted, Quickly Back to Work 2 (QBW2), with the aim of testing the effectiveness of some of the components. The results were compelling: Twice-monthly meetings increased subsequent employment rates by 10% over the next two years compared with the control group, which attended meetings only every 13 weeks.

Detailed analyses show that men and women both experienced large effects, but the dynamics were remarkably different. Women found jobs faster, while men did not. However, men had more stable employment afterwards, leading to sustained positive effects in the longer term.

A different study used observational data from Danish administrative registers to study the dynamics of transition rates from employment to unemployment around the time of meetings [7]. They found that the job-finding rates increased dramatically during the week a meeting was held, and then the effect tended to taper off over the next eight weeks or so. However, when the next meeting was held, the job-finding rate increased again. Hence, the effect of a string of meetings tends to be a gradual increase in the exit rate from unemployment to employment.

Spurred on by these successes, Denmark’s National Labour Market Authority decided to test the case-worker-based approach on long-term recipients of social assistance (the less-employable segment of income transfer recipients) and on sick-listed individuals. In this case, the results were negative. While there was a marked increase in the exit probability from social assistance, there was no corresponding exit into employment. Rather, many social assistance recipients went onto disability benefits, which was hardly the program’s intention. For the sick-listed, there was a similar effect.

On the basis of these tests, one is tempted to conclude that increasing the frequency of meetings makes clear sense only for employable workers—those who are ready to go out and search and whose skills are in demand in the labor market.

Additional advantages

In addition to the evidence that more frequent meetings help to increase job-finding rates and lead to more stable employment trajectories, there appear to be a number of other advantages to this approach relative to traditional activation tools.

There are no measurable lock-in effects associated with a meeting. Most activation programs have sizable lock-in effects. This implies that meetings can be an effective tool early in the unemployment period, when a worker’s chances of being rehired are at their highest. Getting a worker reemployed quickly is crucial in light of evidence that firms are less likely to hire a worker the longer he or she has been unemployed.

The more-frequent-meeting approach is very easy to implement. No course curricula have to be developed, and no private providers need to be hired to provide training. At most, it requires hiring extra case workers in order to accommodate the increased frequency of meetings.

The policy is easily adaptable to cyclical changes. Extra case workers can be hired when unemployment is high. Conversely, the dismissal of surplus case workers may not be necessary even when unemployment is low, if case workers either prefer other work or have a certain degree of natural job mobility. Still, it might not even be necessary to adjust the number of case workers, just their tasks: In periods of cyclical upturn, case workers can focus on intensifying meetings, while in downturns their focus can shift to persuading firms to use job centers, establishing networks among employers, and so on.

Meetings may have positive general equilibrium effects. New research has shown that during the QBW1 experiment, which occurred during an upturn, vacancy durations fell in the municipalities where the experiment was implemented, relative to other locales [8]. The study did not find a similar effect for QBW2, which took place at the beginning of the economic crisis in the late 2000s.

The Danish Economic Council, in their fall 2012 report, found that municipalities with higher meeting frequencies also had lower unemployment rates. Others have shown that the job-finding rates of the control group were negatively affected, although not as much as the positive effect on the treatment group [9]. That study also shows a positive effect of the experiment on the stock of vacancies—so not only were vacant positions filled faster, firms opened even more vacancies because they could fill them quickly.

Since meetings are simple tools, evaluation of their implementation or intensification is quite easy using randomized experiments (or other evaluation techniques). Moreover, changes in the use of the tool—monitoring versus counseling, timing, frequency, matching case workers to clients—can easily be evaluated.

It can lead to more positive perceptions among the unemployed of the activation policies pursued, as they may have more influence and feel that their ideas and concerns are being dealt with. They may also feel a sense of empowerment that causes them to improve their own job search strategies. Moreover, because there is no reduction in the time available to conduct a job search, the approach does not raise any real ethical concerns.

More meetings may lead to better activation, to the extent that the case worker gets to know the unemployed worker and his or her needs better.

This is not to advise policymakers to completely abandon activation policies. Rather, it is to propose that they be used in a more strategic and targeted fashion.

Limitations and gaps

There are obvious limitations to the use of meetings. For one, meetings between workers and case workers will not be useful unless there is valuable information and advice to be shared. Insofar as there are limits to how much advice and information can be shared, there is an upper limit as to the number and frequency of useful meetings.

We do not really know what makes meetings so effective. Is it the stick or the carrot (counseling and advice versus monitoring and sanctions), or both? A survey suggests that meetings focusing on counseling more often have positive effects than monitoring meetings [4]. One study from that survey finds that clients of case workers who are less focused on a cooperative and harmonious relationship have higher employment rates. The literature on the effectiveness of sanctions appears to support the monitoring aspect of meetings.

Other studies suggest that the case worker’s network on the demand side—employers—is also very important. This is an area where more research could lead to more insight into the behavioral mechanisms underlying the positive effects of meetings, as well as for the formulation of policy.

Another limitation is that meetings do not appear to work for less employable individuals. More specifically, they seem to work in an unanticipated and undesirable way, leading to higher transition rates out of the labor force. One reason for this might be that, for meetings to work, there has to be a demand for the skills that the worker possesses. In essence, recipients of unemployment benefits are workers with some skills, and therefore boosting their search activity may work. For less employable workers, the demand is smaller, and therefore meetings may not be as effective in helping these workers to find jobs. The increased transition rate into disability benefits might be one consequence of this. If it makes no sense to talk about job search, and there is no strict protocol as to what to discuss at the meetings, then perhaps the time at the meetings is better spent on other things.

The external validity of these results may obviously be questioned. Although meetings have beneficial effects at the individual level, and some studies show positive general equilibrium effects, others are less positive. One study uses the parameters from an analysis of QBW1 in a general equilibrium model to find only modest reductions in the resulting equilibrium unemployment rate [9]. Another shows that, in France, positive effects in the short term tend to disappear in the longer term, and to come partly from displacement effects of other workers, thus yielding no reductions in unemployment in the longer term [10].

Summary and policy advice

Meetings are an inexpensive policy option, they can easily be scaled up or down, their content can easily be varied (such as switching from counseling to monitoring), and they carry no lock-in effects (making them an effective tool for early intervention in a downturn, when interventions are typically most effective). In short, meetings work.

Thus, policymakers should be strongly encouraged to give greater weight to contacts with their employable clients (unemployed workers and possibly also firms) relative to traditional activation policies. At best, traditional activation policies have shown meager effects; at worst, they are damaging. At any rate, it is clearly much more expensive to provide training courses for an unemployed worker than it is to invite him or her in for a meeting once in a while.

For this reason, a modest shift toward more reliance on meetings and less on traditional activation policies could be beneficial in the sense that it could lead to a simultaneous reduction in unemployment and in the costs of ALMPs. In these budget-constrained times, that is not a bad thing.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Michael Rosholm