Elevator pitch

Most public expenditure on childcare in the US is made through a federal program, the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), established as part of landmark welfare reform legislation in 1996. The main goal of the reform was to increase employment and reduce welfare dependence among low-income families. Childcare subsidies have been effective in enabling parents to work, but apparently at some cost to the well-being of parents and children.

Key findings

Pros

The CCDF childcare subsidies increase employment among low-income parents.

The subsidies encourage parents to invest in their own potential by engaging in educational and job-training activities.

To the extent that childcare subsidies encourage human capital investment, they may lead to long-term economic self-sufficiency.

Childcare subsidies coupled with an employment requirement facilitate the move from welfare to work among low-income parents.

Cons

The way the CCDF is designed to operate may discourage low-income parents from looking for, and providers from offering, high-quality care.

Signature features of the current childcare policy (the work requirement and the relative freedom of parents to choose carers) appear to have adverse effects on the well-being of children.

Author's main message

Designing a childcare subsidy policy that promotes parental employment and improves the quality of childcare at the same time is difficult, if not impossible. Given the conflict between the two goals, childcare policy should be more about children and less about parental employment, as high-quality childcare has significant private and societal benefits. The employment goal could be achieved through more direct policy instruments.

Motivation

Employment is a vital indicator of economic self-sufficiency and independence for women. In recent decades there have been significant advances in women’s participation in paid work in industrialized countries. Childcare has thus become a topic of major interest for policymakers trying to figure out how to ensure that parents—especially those on low incomes—can afford reliable, safe, and quality childcare, and how it should be financed.

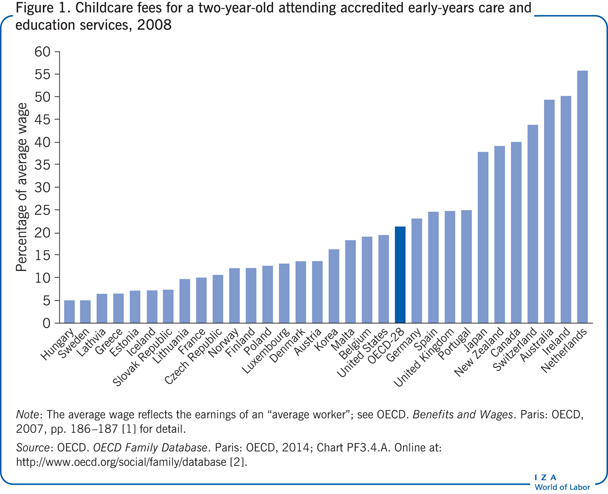

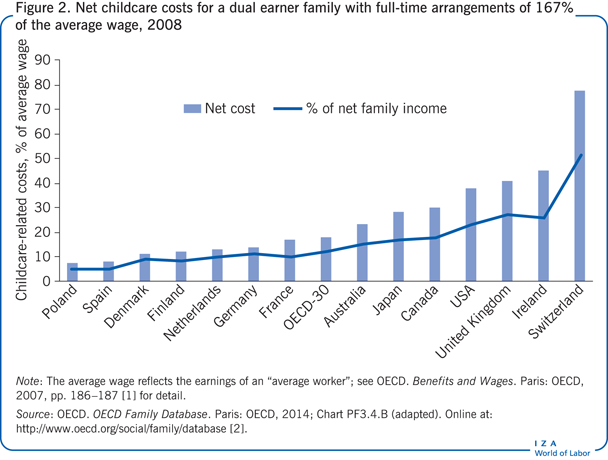

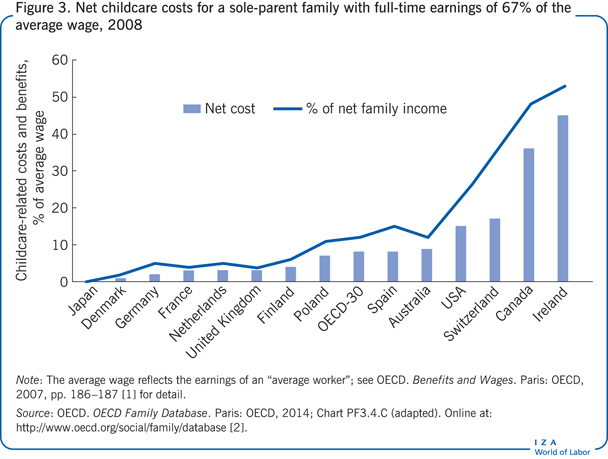

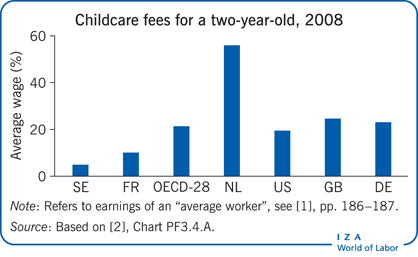

Childcare fees are paid by parents to childcare institutions—this could be day-care centers or family day care—for services provided to them and their children. They can differ significantly by country (see Figure 1). Fees can be reduced for low-income families and sole parents (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). In order to ensure access for families with limited means (“to address equity concerns”) and to ensure lower costs for larger families (“to address demographic objectives”) childcare fees usually differ by the number of children in care and may decrease with children’s age. Hence, countries try to help parents by providing a range of tax reductions and cash benefits to reduce the net cost of childcare, for instance through (income-tested) childcare benefit support and targeted rebates. These net childcare costs can be significantly lower than gross childcare fees [2].

In the US, childcare subsidies have long been seen as important to help low-income parents move from welfare to work. But childcare issues are not unique to the US and increasingly receive attention in Europe as well. In the US, the CCDF is the primary fund for childcare. Its twin goals are promoting parental employment by making childcare more affordable, and improving the quality of childcare. It is important to understand the design features of the CCDF and the fund’s implications for US families in order to draw inferences as to the potential of similar policy reforms being debated in Europe.

Discussion of pros and cons

The goals of the CCDF

Childcare is expensive in the US, accounting for a significant share of the budget of parents, especially those on low incomes. Despite the sharp financial burden imposed on families by the cost of childcare, the role of government in financing childcare was limited prior to the mid-1990s, the cost being largely borne by parents. But with the passage of welfare reform in 1996 and the introduction of the CCDF, the government has assumed a much more active role.

Prior to the CCDF, childcare assistance was administered through a fragmented array of individual programs, each of which operated independently of the others. The policymakers thought that the consolidation of programs under the CCDF would improve parental choice and access to childcare services, give states more flexibility in the design and control of their own childcare programs, and ultimately help to bring about the welfare reform’s primary goal of increased employment.

The CCDF supports the childcare expenses of approximately 1.7 million children every month while their parents are at work, seeking work, or participating in a work-related activity such as job training or education. In the fiscal year 2010, states spent about US$9.5 billion in CCDF funds.

Implications of the CCDF for parental employment

Most childcare expenditures are disbursed so that a parent can work. Therefore, it is no surprise that childcare subsidies have been recognized by policymakers as a key policy tool to encourage employment among the parents of young children. A childcare subsidy can be seen as a way of reducing the effective price of care that parents face in the market and of increasing the net returns from working.

Motivated by the emphasis that the CCDF places on promoting employment, a number of studies have investigated the effect of these subsidies on parents’ ability to take on work [3]. The consensus finding is that childcare subsidies do increase employment among low-income parents with young children. The evidence is clear that subsidies provided by the CCDF constitute a key policy instrument that government can use to promote employment among the target population of low-income parents with young children.

Implications of the CCDF for human capital investment, long-term self-sufficiency, and transition from welfare to work

The eligibility rules for the CCDF require parents to be engaged in state-defined acceptable work activities. What is referred to as a “work activity” is typically employment, but education and training are also accepted by many states—as long as parents meet other eligibility conditions.

The main argument in favor of these activities is that they should help low-income families to become economically self-sufficient in the future. Data show that a non-trivial proportion of subsidy-eligible parents do in fact engage in these activities. Despite the potential significance of human capital investment in promoting self-sufficient and stable employment, relatively little research has been devoted to examining the effect of childcare subsidies on employment-related activities. One notable exception is a 2011 study that finds that childcare subsidies in the US encourage parents to invest in their own human capital by engaging in education and job-training activities [4]. One implication of this finding is that a childcare subsidy regime like the CCDF, which emphasizes rapid movement into employment, can also assist low-income parents by giving them the opportunity to improve their skills and knowledge. This is an encouraging sign for the ultimate goal of helping a needy population to achieve self-sufficiency in the long term.

The CCDF subsidies can also contribute to parents’ ability to retain employment in the long term by reducing disruptions to work and enabling stable work schedules. One study examines the effect of childcare subsidies on low-income parents’ experience of work disruptions related to childcare [5]. The authors find that such work disruptions are less likely among recipients of subsidies.

Along similar lines, another study considers the question of whether childcare subsidies play a role in facilitating a transition from non-standard work schedules (i.e. working outside the hours of 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. between Monday and Friday) to standard ones [6]. This may be an important consideration from the point of view of employment retention, because jobs performed during non-standard hours are less likely to provide opportunities for health insurance, pension benefits, job training, and career advancement. It was found that childcare subsidies are associated with a significant increase in acquiring employment with standard schedules. Furthermore, the size of the impact of subsidy receipt on standard employment is higher among welfare participants than non-participants, which indicates the importance of these subsidies in efforts to move low-income families out of welfare and into employment. In fact, there is evidence that the CCDF subsidies are effective not only in increasing employment, but also in reducing the need for welfare support [3]. All of these findings are encouraging, in the sense that they reflect the efficacy of the CCDF subsidies in promoting economic self-sufficiency through employment both in the short and long term.

Potentially negative implications of the CCDF for the well-being of children and parents

The above discussion leaves little doubt that CCDF subsidies have been successful in accomplishing one of the two key program goals—to promote economic self-sufficiency among poor families by helping them to move from welfare to work. Several design features embedded in the CCDF system are imperative in accomplishing this goal. First and foremost, eligibility for a childcare subsidy is conditional on fulfilling the requirement of being in work or seeking work, or engaging in job training or education. Second, the CCDF emphasizes the principle of “parental choice,” which means that parents can purchase childcare from most legally operating providers that meet certain health and safety standards required by states.

Quality childcare versus parental employment: Irreconcilable goals?

The evidence on the second goal of the CCDF—to promote child development and success at school by improving the quality of childcare—is less than encouraging. In fact, there are growing concerns that the twin goals of the CCDF—to encourage employment and to advance the quality of childcare—are in conflict with each other [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. It is argued that the tension between the two goals is exacerbated by the current structure of the CCDF, which places too much emphasis on the goal of increasing parental employment and too little on enhancing the quality of childcare.

A growing literature documents that developmental experiences during a child’s first few years are critical to establishing the foundation for achievement throughout life [12]. This period is especially important for children receiving CCDF subsidies, since most of them come from disadvantaged families and face a gap in preparedness for school and educational achievement relative to their peers. Accordingly, the remediation efforts designed to reduce or eliminate this gap, such as high-quality childcare programs targeted at low-income families, are likely to be most effective during these early years.

The importance of these efforts is further heightened by the widespread evidence that the quality of childcare in the US is mediocre on average, and lower than in most European countries, based on the metrics developed by child development psychologists. Therefore, the CCDF is likely to have far-reaching implications for millions of the US’s poor children that extend beyond increased employment and reduced welfare participation among low-income parents.

Freedom of parental choice and quality of care

The CCDF has several features that may indirectly influence the quality of care received by subsidized children. One of them is the emphasis on “parental choice.” While the greater flexibility allowed by “parental choice” may facilitate parents’ rapid transition out of welfare and into employment, it also raises concerns over whether it induces parents to substitute quantity of care for quality. After all, parents are allowed to purchase care from most legally operating childcare services, including unregulated relatives and in-home caregivers, as long as they meet basic health and safety standards. In many states, family day care homes are not even required to register or obtain a license permit in order to operate—again, provided they meet basic health and safety standards. Without strong quality requirements, it is also possible that parental decisions on childcare are guided by a range of factors unrelated to quality, such as personal bias, cultural and religious expectations, and convenience. In fact, there is evidence to indicate that parents spend little time looking for childcare, and that they lack basic information about what constitutes high-quality care and how to identify it.

Therefore, it is not surprising that there is widespread use of unregulated care among CCDF parents. For example, about 80% of CCDF children are served in regulated settings, while the rest receive care under arrangements that operate legally but are not subject to regulation. Of children served in unregulated settings, almost two-thirds are cared for by relatives, and the rest are served by non-relatives. These are not required to meet basic health and safety standards, minimum training requirements, or background checks, and they are not subject to regular inspections. Many states do not enforce even such basic standards as fingerprinting, background checks, and first-aid training for providers. Accordingly, the quality of care in these informal settings is likely to be low.

Another detrimental feature is that the increased employment associated with the receipt of childcare subsidies may lead to dramatic changes in the home environment that are not always positive for the parents, such as increased stress and anxiety caused by the requirement to maintain employment in order to keep a childcare subsidy, which can often be exacerbated with demanding work schedules at little additional financial reward.

Supply-side constraints on the quality of care

Additionally, the CCDF may create distortions on the supply side of the market that may also have negative consequences for the quality of childcare. For example, quality standards mandated by the CCDF are not tied to thresholds that would be optimal from the perspective of child development. In fact, most of the quality requirements are minimal; hence, many providers may still fall below the optimal levels of quality, even if they meet all the mandated standards.

States are required to spend a minimum of 4% of their annual CCDF allocation to fund such initiatives as teacher training and education, improvements to health and safety conditions, and establishing quality-rating systems [9]. In practice, there is wide variation in the proportion of total CCDF expenditures allocated for quality-related activities across states. Overall, quality-related expenditures account for about 12% of total CCDF spending. Despite that, the actual level falls far below what is required to ensure children’s healthy development in most states.

Furthermore, increased volatility in revenue streams for childcare providers caused by making subsidy eligibility conditional on employment may discourage providers from offering high-quality services. Specifically, childcare providers who rely heavily on subsidized children as a source of revenue may experience sharp fiscal shortfalls when parents lose eligibility or use their subsidy to pay another provider [9]. According to CCDF rules, the amount of subsidy to be paid to providers is supposed to be set at the 75th percentile of the price distribution in the local childcare market. However, this is only a recommendation, and in practice most states set lower rates. This further limits parental access to high-quality early care and imposes an additional financial strain on providers. Frequent interruptions to childcare caused by these supply-side constraints could then have adverse effects on children’s development.

A federal government response to the concerns

Some of the concerns described above are recognized in a recent report published by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which calls for new regulations that would better ensure children’s health and safety in childcare and promote readiness for school. Under the proposed regulations, states would require all CCDF-funded childcare providers to receive health and safety training, comply with applicable state and local fire, health, and building codes, undergo comprehensive background checks (including fingerprinting), and be subject to on-site monitoring. The proposal also recognizes the need to give parents the tools that would help them to identify high-quality care. Accordingly, it introduces measures to ensure that states make information available to parents on the health and safety and licensing status of care providers through user-friendly websites.

On the one hand, it is encouraging to see the emphasis on addressing the quality issues associated with CCDF subsidies. It appears as an especially correct move to focus on the need to inform parents about the benefits of high-quality childcare and to help them to identify such care, given the evidence suggesting that parents are not well informed.

On the other hand, it is not clear whether stricter regulations are, ultimately, the answer to achieving the goal of improved quality of care. First of all, increased regulation can be effective only if it is enforced effectively. But effective enforcement in an environment with hundreds of thousands of providers would require major resources and lead to increased bureaucracy [7]. Second, the evidence suggests that the most important contributors to care quality are not factors that can be regulated, such as child–staff ratios or experience, but rather the intangible factors that characterize the nature of the relationship between providers and children, such as enthusiasm, energy, and motivation [7].

Academic responses to the concerns

Concerns that a policy regime with a disproportionate emphasis on employment may have unintended consequences for children’s development and parental well-being have motivated a recent wave of studies to focus explicitly on this question. Before summarizing their findings, it is useful to recall the many ways in which receipt of subsidies conditional on having or seeking employment can affect the well-being of children and parents. Two have already been discussed: the reduction in the amount of time a working mother has to look after her children; and the distortion of incentives to purchase high-quality care by parents and to offer such care by providers.

But there is another effect of subsidies that we have not yet mentioned: by reducing parental expenditure on childcare, income is freed up for parents to spend on private consumption. The extent to which additional income is spent on themselves rather than on goods and services that benefit a child, such as educational books, software, and toys, is not well known. In the end, the net effect of a childcare subsidy policy with an employment requirement on the well-being of both children and parents remains ambiguous.

The first study to focus on these concerns assesses the impact of CCDF subsidies on a wide range of child outcomes in cognitive and behavioral domains [8]. Drawing on detailed data from the kindergarten cohort of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study conducted in the US, the authors document that subsidy receipt in the year before kindergarten is associated with lower reading and math test scores, reduced eagerness to learn, and more behavioral problems in kindergarten.

A follow-up study by the authors revisits the same question in a more comprehensive framework in which they develop a model that details the multiple mechanisms underlying the link between the receipt of subsidies by parents and children’s well-being [9]. The study is careful in attempting to take into account the non-random selection of families into subsidy receipt. It does so by exploiting the geographic variation in the distance that parents must travel from their homes to reach the nearest social service agency administering the subsidy application process. The results again point to negative effects of CCDF subsidies on tests of cognitive ability and behavior reported by teachers in kindergarten.

In related work, the same authors document that subsidies served under the CCDF lead to an increased prevalence of excess body weight and obesity among children [10]. They also examine whether childcare subsidies influence other dimensions of family well-being, specifically the physical and mental health of mothers and the quality of child–parent interactions [11]. In the latter work they conduct analyses using data from three nationally representative surveys in the US that provide numerous measures of family well-being. Once again, the results indicate consistently that childcare subsidies are associated with worse maternal health and poorer interactions between parents and their children.

Limitations and gaps

It is almost indisputable that child subsidies from the CCDF help low-income families leave welfare and find employment. Studies from the US, Canada, and a number of European countries all point the same way. There is also growing evidence that a policy regime that makes receipt of childcare subsidy conditional on parental employment puts both child development and parental well-being at risk.

However, the evidence on the effect of subsidies on outcomes other than parental employment comes almost exclusively from the US. This is no surprise, as the US is nearly unique in tying eligibility for childcare subsidies to employment. Therefore, questions remain about how far the US evidence can be a reliable guide to the effect of similar policies in Canadian and European contexts, which differ from the US in important ways.

Finally, large-scale studies with carefully crafted randomized designs are needed to shed light on the mechanisms through which childcare subsidies influence child and parental well-being.

Summary and policy advice

The CCDF is the primary assistance program for childcare services for working mothers in the US. It strongly emphasises employment, requiring parents to work or seek work, or engage in work-related training or education as a condition of receiving childcare subsidies. Accordingly, it is well established that CCDF subsidies have been effective in moving low-income populations out of welfare and into jobs. However, there is growing evidence that this is at the expense of the well-being of both children and parents.

Given the significant economic and social payoffs associated with high-quality childcare, future government proposals should consider reorienting the design of the CCDF to place more emphasis on improved quality of care. Lessons could be learned from Head Start—another federal program—which provides education, health, and nutrition services to low-income children and their families, but without requirements concerning parental employment. In conclusion, childcare policy should be more about children and less about getting parents into work.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Erdal Tekin