Elevator pitch

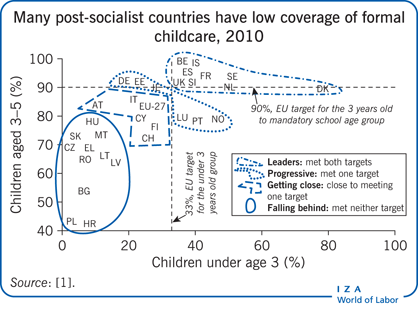

In 2002, the EU set targets for expanding childcare coverage, but most of the post-socialist countries are behind schedule. While childcare expansion places a heavy financial burden on governments, low participation in the labor force by mothers, especially those with children under the age of three, implies a high potential impact. However, the effectiveness of childcare expansion may be limited by some common characteristics of these countries: family policies that do not support women’s labor market re-entry, few flexible work opportunities, and cultural norms about family and gender roles shaped by the institutional and economic legacy of socialism.

Key findings

Pros

Low maternal employment despite high overall female participation in the labor force calls for appropriate policies to increase maternal employment.

There is evidence that subsidized childcare for young children can increase maternal employment.

The effectiveness of childcare expansion can be augmented by changes in parental leave policy that do not require large additional resources.

Better work–family policies can support government goals of increasing fertility rates without sacrificing maternal labor force participation.

Cons

Expanding subsidized childcare would place a high financial burden on relatively poor post-socialist countries.

Family policies in these countries have generally moved away from encouraging the employment of mothers.

Cultural norms against the employment of mothers with very young children and a history of mistrust of institutional childcare facilities may hinder the effectiveness of policies.

The lack of flexible and part-time work opportunities may constrain the labor force participation of mothers with young children.

Author's main message

Expansion of childcare in the post-socialist countries of Eastern and Central Europe is crucial for improving low maternal labor supply and fertility rates. To realize the potential benefits of expansion, however, other limiting factors need to be addressed. Administrative and tax barriers to flexible work opportunities need to be removed, elements of diverse family policies (such as long periods of maternal leave at low pay) need to be adjusted to increase fathers’ involvement in childcare, and historically rooted views reflecting traditional gender roles and a mistrust of institutional childcare for young children need to be reshaped.

Motivation

In 2002, the EU set targets of 33% for formal childcare coverage of children under three and 90% for children between three years old and the compulsory school age by 2010 (known as the Barcelona targets) to improve gender equality in the labor market by removing barriers to maternal participation [1]. While EU member states have made progress, a group consisting mainly of post-socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe remains well behind. Coverage remains low for both age groups in some countries (Croatia, Bulgaria, and Poland), and most countries are far from the target for children under three (with the exception of Estonia and Slovenia). For the post-socialist countries that are falling behind and that are considerably poorer than the EU average, achieving the Barcelona targets poses a substantial financial burden.

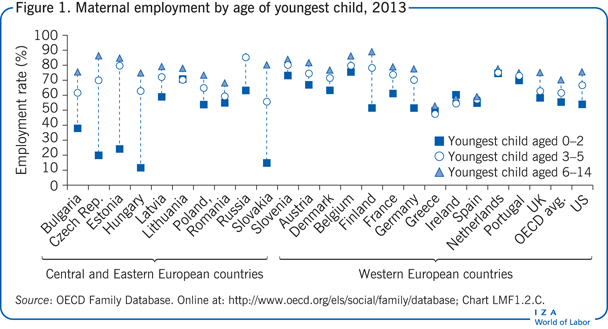

At the same time, maternal employment rates suggest substantial room for improvement, especially for mothers with children under three (Figure 1). While employment rates for mothers of older children (above the age of six) are not out of line, and some are even among the highest in the EU (the Czech Republic, Estonia, and Slovenia), low employment rates for mothers of younger children reflect low childcare coverage: low maternal employment rates for mothers of three- to five-year-olds and very low rates for mothers of children aged two and younger. Cross-country differences, however, cannot be fully explained by the variation in childcare availability. For example, some countries, such as Poland, have high maternal employment rates despite low childcare coverage rates. Thus, while childcare availability is important, some factors specific to post-socialist countries may impede the effectiveness of childcare expansion unless coupled with policy changes aimed at removing these constraints. To determine whether to invest in childcare expansion and whether other policy changes are also needed, countries require accurate estimates of the potential benefit—the increase in maternal activity—given the country-specific context.

Discussion of pros and cons

Evidence on the childcare effect

Estimating the causal impact of childcare availability on maternal labor supply is complicated by the fact that childcare availability is correlated with other regional and individual factors that also influence labor supply. One strand of research focuses on structural models of the labor supply decision and uses regional and time variation in childcare availability or prices to identify the impact, with highly heterogeneous results. Surveys of this evidence have noted that these studies differ in methodology, data, the age of children, institutional and hard-to-observe preferential factors and that the endogeneity of childcare availability may bias the estimates [2]. A more recent strand of research takes advantage of quasi-experimental settings to better identify the childcare effect. These use some exogenous variation in childcare availability—policy changes or eligibility cutoffs based on birth dates—to compare the labor market activity of mothers who should be similar in all relevant characteristics except access to institutional childcare.

Quasi-experimental evidence: The context matters

Quasi-experimental studies provide strong evidence of a causal effect of childcare availability on maternal labor supply. However, the results are highly dependent on context. A recent study that summarizes lessons from a comparison of a set of quasi-experimental studies for the US and several Western European countries suggests that the effectiveness of childcare expansion depends on several contextual factors. First, the scope for policy to effectively increase maternal labor supply depends on the existing level of maternal labor force participation; if it is high, the effect will be small. Second, the interaction of childcare expansion with other policy elements, such as child-related parental leave, also influences the effect. Finally, social norms about gender and maternal roles are also important determinants, in that more traditional and less egalitarian role models can discourage mothers’ labor force participation [3].

Empirical estimates of the effect of childcare availability cover mainly Western countries; however, the interpretation of their results provides some insight into how the effects may differ in post-socialist countries. Evidence from a range of countries supports the notion that policymakers should consider interdependencies when evaluating the potential effects of policies to support maternal employment by expanding childcare provision. A study for the US found no evidence of a significant effect from the introduction of free universal preschool for four-year-olds, since maternal employment was already fairly high for mothers of children of this age [4]. A very small effect was estimated for France, where a 50% average reduction in childcare costs led to only a one percentage point increase in the already high labor force participation of mothers [5]. A larger effect was found in Spain, where the introduction of universal full-time preschool led to a three percentage point increase in a much lower maternal labor force participation rate [6]. In Germany, where maternal employment rates were very low even though female education levels were high, the introduction of a legal claim to a place in kindergarten in 1996 led to an increase of six percentage points in maternal employment [7]. Since the labor force participation of mothers with children under three is very low in post-socialist countries, the findings for Spain and Germany suggest a large potential impact in post-socialist countries.

The study for Spain noted that in a context of very short legislated maternity leave and rigid labor market conditions, the introduction of universal full-time preschool was not enough in itself to spur a large increase in maternal employment despite the low level of maternal employment [6]. Childcare expansion may also be ineffective in increasing maternal labor supply if social norms are not supportive of maternal employment. Traditional views on gender roles contribute to the fact that in Spain many women permanently exit the labor force after giving birth, despite the increase in childcare availability [6]. In France, on the other hand, cultural norms are very supportive of mothers working, leading to a high maternal employment rate that was not greatly affected by additional childcare expansion [5]. Similar to public sentiment in Spain, people in post-socialist countries have fairly traditional views about maternal employment, with a strong preference that mothers of children under three care for them at home. There are also few options for flexible work schedules. Both of these factors are likely to limit the effectiveness of childcare expansion in post-socialist countries.

Evidence from the one quasi-experimental study that estimated the effect of childcare availability in Hungary, a post-socialist country, is in line with these findings. The study focused on mothers of children at age three, an age at which high-coverage public kindergarten becomes available, parental leave ends, and societal preferences regarding whether mothers should stay at home to take care of their children change sharply. Maternal labor force participation increases by 31 percentage points among mothers with children at this age, with 7.6 percentage points of the increase explained by the increased availability of subsidized childcare. As expected based on the very low maternal employment rate before children reach the age of three, the effect is high compared with the increase found in Western countries with already high labor force participation rates. At the same time, the result for Hungary highlights the importance of other contextual factors particular to most post-socialist countries—maternal leave policies and societal preferences—since childcare availability explains only a quarter of the overall rise in maternal activity when children reach the age of three [8].

Cross-country evidence on family policy measures

Much of the empirical evidence on the effects of an expansion in childcare on maternal employment comes from single country analyses that focus on the childcare effect. However, another strand of the literature focuses on testing the effect of several elements of family policy and cultural norms on maternal labor supply based on cross-country comparisons. These studies generally support the view that in addition to the availability of childcare (especially for children under three), the existence of well-paid maternal leave that is neither too short nor too long, flexible job opportunities, and cultural support for maternal employment lead to smaller differences in the employment participation and working hours of mothers compared with women without children [9]. Because mothers in post-socialist countries face constraints in several of these areas simultaneously, these results again suggest that the expansion of childcare alone may not be effective in increasing maternal labor supply to the levels seen in Western countries.

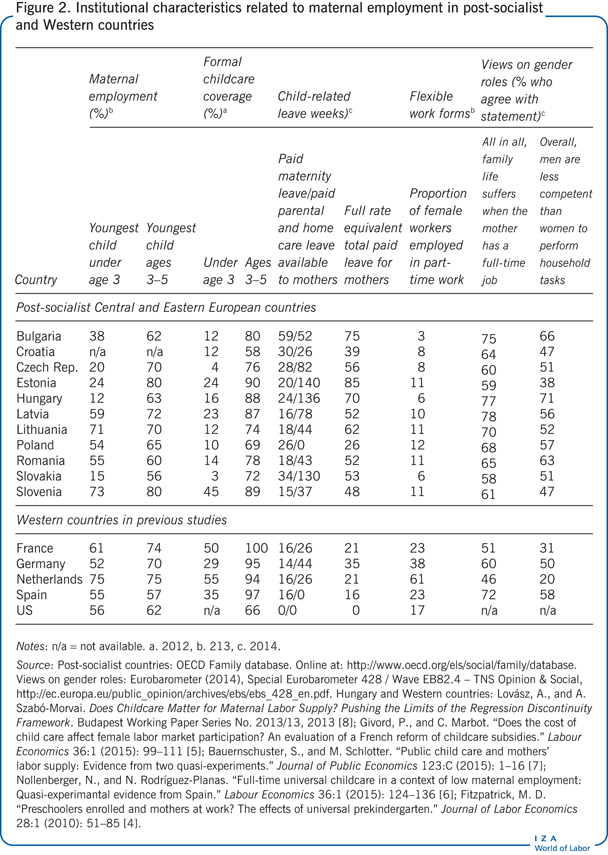

Relevant characteristics of the post-socialist context

Studies assessing the historical evolution of family policies in post-socialist countries emphasize that the countries should not be treated as a homogeneous group because of the differences among them in historical context and reform paths. However, there are some commonalities related to the socialist legacy that may influence the effects of childcare expansion on maternal employment, as discussed above [10]. Figure 2 summarizes some of these key characteristics that affect maternal employment in post-socialist countries, as highlighted in the economic and policy literature. For comparison, it also includes some Western countries. But while there are some commonalities, there is also considerable variability in some factors and maternal employment outcomes among post-socialist countries.

Low employment of mothers with young children

With the notable exceptions of Lithuania and Slovenia, low employment rates for mothers with children aged up to two years have persisted in most post-socialist Central and Eastern European countries, but with considerable variation among them. These differences cannot be explained by differences in childcare coverage, which is considerably lower than in Western European countries. For example, Poland has a fairly high rate of maternal employment despite the low childcare coverage for children in this age group, while Estonia has a low maternal employment rate despite its higher childcare coverage.

The evolution of maternal employment has taken a very different path in post-socialist countries than in Western countries, which have experienced a gradual increase in female and maternal employment over the last few decades. Under the socialist system, Central and Eastern European countries had very high levels of female employment and a declared commitment to women’s equality. When these countries transitioned to a market-based economy and experienced severe economic recession, female employment fell [11]. But while socialist countries had promoted maternal employment with generous family policies and an extensive childcare system, there was no concurrent shift in the distribution of household duties, mothers worked in lower-paying jobs, and employment was not their own choice but rather imposed on them by state policies. These factors resulted in what has been termed a socialist legacy of anti-feminism that still influences societies and policymaking in the region [12].

Low coverage of childcare institutions for children under the age of three

The low current levels of childcare coverage in post-socialist countries also reflect a very different trajectory than in Western countries. Public childcare was extensive during socialism, but transition led to a dismantling of the centralized system. Provision was moved to local governments, resulting in a decrease in funding and quality and to many closures, especially of institutions for children under the age of three [12]. A further important element of the socialist legacy concerns the institutional structure of the childcare system, especially in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. While kindergartens were considered educational institutions and overseen by the ministry of education, nursery schools were considered health care institutions and were overseen by the health ministry. This led to a very different atmosphere and quality in the two types of institutions: a general dislike of nursery schools, and a strong, persistent belief that care within the family is better than nursery schools for children under the age of three [10]. Because of these preferences and the emergence of a large share of the population not engaged in the labor force, childcare by grandparents became widespread in these countries. Childcare expansion may therefore only affect women in families with no grandparents available to help with childcare unless preferences can be changed to favor institutional childcare, even for children younger than three.

Very long or very short maternal leave

In addition to the extensive childcare system, most socialist countries had a generous system of child-related benefits aimed at supporting female employment. But following the transition, the emphasis shifted to moving childcare duties back to the family, specifically women [10]. The economic environment also influenced the path of reforms taken, leading to both common trends and to variations in family policies. Budgetary constraints led to a decline in cash benefits, though total spending on family policies as a ratio of national income remained fairly high. Recent austerity measures and concerns over low fertility rates have kept governments from making further cuts in order to keep women within the household, and some countries have even introduced reforms aimed at moving more women out of employment and into the domestic realm.

Maternity and parental leave available to mothers in post-socialist countries is generous compared to that available in the Western countries shown in Figure 2. Some post-socialist countries provide very long (up to age three or beyond) though relatively low-paying parental leave to all mothers. Research suggests that this long leave at low pay may result in mothers (especially those who are low-skilled) becoming detached from the labor market, allowing their skills to depreciate, as well as in increased statistical discrimination against mothers and other women, whom employers assume may have children in the future and whom they therefore judge to be less dependable, more costly employees [9]. At the other extreme, Poland does not offer parental leave at all, and maternity leave is means-tested and available only to relatively few mothers. When maternal leave is too short, it may constrain the ability of women to re-enter the workforce due to the lack of job protection after giving birth and may discourage mothers in higher-income households from returning to work [9].

Compared with countries that offer short or no maternal leave (such as Poland), countries that have long maternal leave with low pay (such as the Czech Republic and Hungary) have more flexibility to reform leave policies to promote mothers’ return to the labor market without unduly increasing the financial burden on the government. These countries have more fiscal space to restructure their leave policies without incurring further costs. Lithuania, Romania, and Slovenia already provide medium-length, well-paid leave that is similar to that provided in Western countries with the highest rates of maternal employment. This leave design balances the goal of job protection with incentives to return to work that encourage women to have children without sacrificing their careers as a result of long interruptions.

Another important aspect of the design of leave policies is how well they enable and encourage fathers to share in childcare. Among the Western countries in Figure 2, those that explicitly encourage a more even distribution of duties between mothers and fathers have the highest levels of maternal and female employment, though the gender gap in leave usage remains large even in countries with the highest levels of gender equality, such as the Scandinavian countries [13]. The post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe offer very short, if any, leave for fathers. These policies reflect a carryover of attitudes from the socialist era. Although socialist governments were among the first to introduce parental leave, such leave was available only to mothers. Referred to as extended maternity leave, it was not indicative of a supportive attitude toward fathers’ involvement in childcare [10]. The post-socialist countries opened up parental leave to fathers only in response to EU pressure prior to their accession to the EU, but the current design and usage pattern of leave policies reflect a generally non-supportive attitude toward paternal leave within society and government.

Inflexible labor markets

The flexibility of the labor market affects maternal employment, though it is not directly related to family policies. In countries where long maternal absences from the labor market are the norm, part-time work may provide mothers with a means of strengthening their attachment to the labor market and keeping their skills up to date, while allowing for a more gradual separation from their child. The employment rate of mothers with young children is strongly correlated with the availability of part-time work opportunities. Figure 2 shows a large gap in the availability of part-time work opportunities between Western countries and the post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern European. While the proportion of women working in part-time jobs in the Western European countries ranges from 23% (France and Spain) to 61% (the Netherlands), in the Central and Eastern European countries it ranges from 3% (Bulgaria) to 12% (Poland). The administrative burden and tax disincentives to hiring part-time and temporary workers are high in the post-socialist countries, leading to inflexible labor markets. At the same time, childcare hours at nursery schools and kindergartens are also rigid and difficult to reconcile with full-time work, but this rigidity could be less of an impediment to mothers’ employment if part-time job opportunities were more readily available. Together, these factors constrain the employment of mothers of young children in many post-socialist countries [12].

Unsupportive societal views

Changing the responsiveness of mothers to policies to encourage maternal employment requires shaping public opinion to counteract a socialist legacy of anti-feminist sentiment and mistrust of institutional childcare for young children, while also ensuring that other policies are in harmony with the goal of increased maternal employment. That means aligning and supporting family policies to ease the rigidity in labor markets by encouraging more flexible work options. Responses to two questions related to gender roles on the Eurobarometer survey of public opinion in EU countries (“All in all, does family life suffer when the mother has a full-time job?”; and, “Overall, are men less competent than women in performing household tasks?”) suggest that people’s views are not much more gender biased in Central and Eastern European countries than in Western Europe and the US. At the high end of the spectrum of agreement with these questions, the percentages of people who agree are not much higher in Central and Eastern European countries than in Spain, while percentages in several post-socialist countries, for example, Estonia, are closer to those in the less traditional Western countries. As one study notes, despite a lack of support for feminism in theory, in practice people in Central and Eastern European countries are not much less supportive of gender equality in everyday life on average than are people in Western countries? [12].

Especially noteworthy, however, is that the legacy of socialist influence on negative attitudes toward maternal employment is particularly strong for mothers of young children. These still-entrenched views may limit the effectiveness of policies to expand childcare among this group of mothers. These views may also explain the absence of public protest against reforms emphasizing home care of young children, and why there has been little pressure on governments to adopt policies promoting the entry or re-entry of mothers into the labor market and greater gender equality [12]. The 2010 European Commission evaluation of progress toward the Barcelona targets also notes the importance of norms related to parenthood, institutionalized childcare, and parental preferences at the country level, stating that it is “important not only to acknowledge these longstanding cultural and normative values about parenthood and childcare, but to also attempt to tackle these perceptions through more public awareness” [1].

Limitations and gaps

While there are estimates of the effect of childcare expansion on maternal labor supply based on reliable quasi-experimental methods for numerous Western countries, direct evidence is scarce for post-socialist countries. The very different institutional and cultural contexts in these countries mean that the effects might differ considerably, potentially constraining the benefits of expanding childcare coverage in post-socialist economies. Previous empirical estimates of the childcare effect in individual (mostly Western) countries, as well as cross-country policy comparisons, all point to the potential for other factors, such as parental leave policies, labor market characteristics, and cultural views, to limit or enhance the effectiveness of childcare expansion. However, there is little direct evidence from any setting on the nature of these interactions. Research is needed to clarify how cultural norms are shaped, and how policies can affect views on what is best for children, mothers, and families. Having such information would be useful for evaluating the effectiveness of childcare expansion in various contexts. One potentially fruitful avenue in this respect would be to apply quasi-experimental methods to structural economic labor supply models [3].

A further limitation is the lack of cost–benefit analyses and comparisons with alternative polices. This is the kind of analysis—as conducted, for example, in the study on Spain—that would be most useful for policymakers, because it takes into account both the potential benefits and the potential costs, which differ for different policy alternatives [6]. Finally, evaluations of childcare and other family policies need to consider maternal, child, family, and societal outcomes in the short and long term.

Summary and policy advice

Low maternal labor supply rates and low childcare coverage rates of children under the age of three in post-socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe suggest a large potential effect of childcare expansion on maternal employment. However, some parts of the socialist legacy hinder the willingness of governments to invest in childcare expansion and reduce the potential effectiveness of such expansion. Anti-feminist sentiment that arose from the inability of the socialist system to equalize gender roles within the household while forcing women to work outside the home, economic necessity that led to the “re-familialization” of family policies in general (dismantling of extensive childcare systems, leave policies that support women staying home), a mistrust of institutionalized childcare for young children, and rigid labor markets and childcare hours have led to low levels of maternal employment and little public support for further policy changes to improve the situation of mothers in the labor market.

It may be more difficult to change attitudes and implement effective policies to encourage maternal employment in these countries than in countries where views on gender roles and maternal employment developed in a more linear and gradual manner, unencumbered by these contextual obstacles. Nevertheless, it is essential to do so. Effective policies in post-socialist countries may also require a different set of tools.

Research has demonstrated the interactions between childcare expansion and other factors, suggesting that badly designed leave systems, the lack of flexible work forms, and unsupportive cultural attitudes may all constrain the effectiveness of childcare expansion in expanding maternal employment. Yet policy targets for increasing maternal employment (for example, the Barcelona targets) did not explicitly include targets and recommendations for other policies besides childcare expansion. Achieving the goal of higher maternal employment and greater gender equality may require the post-socialist countries to take other steps aimed at these factors concurrently. The targets for other policy changes may be modeled after successful policies in Western countries and in the Central and Eastern European countries that have achieved high maternal employment. Slovenia shows that even in a post-socialist context, higher childcare coverage combined with more supportive policies, such as generous but not overly long parental leave, can achieve positive outcomes similar to those in Western countries that have high maternal employment.

Parental leave should be reformed to encourage more sharing of childcare duties by fathers by expanding paternity leave and by offering shorter, better paying parental leave. This policy combination not only protects mothers from job loss but ensures job continuity and decreases the motivation for employers to discriminate against women. At the same time, the childcare system needs to become more flexible in meeting the employment needs of mothers (such as more flexible hours and days) and the developmental needs of children. Governments need to lift administrative and tax barriers that impede the development of flexible forms of work. Investment in childcare quality must accompany investment in childcare expansion, to overcome dissatisfaction with institutional childcare. Finally, attitudes within government and among the population need to change, so that people understand that a more equal division of childcare and work duties between mothers and fathers would not only benefit mothers by allowing them to participate in the labor market, but would also better address national concerns about declining fertility rates and labor supply in aging societies where young mothers form an important part of the potential workforce.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author is also grateful to Ewa Cukrowska-Torzewska and Ágnes Szabó-Morvai for joint work on previous research related to the topic and their help in collecting relevant data sources.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Anna Lovász