Elevator pitch

Managers are supervising more and more workers, and firms are getting flatter. However, not all firms have been keen on increasing the number of subordinates that their bosses manage (referred to as the “span of control” in human resource management), contending that there are limits to leveraging managerial ability. The diversity of firms’ organizational structure suggests that no universal rule can be applied. Identifying the factors behind the choice of firms’ internal organization is crucial and will help firms properly design their hierarchy and efficiently allocate scarce managerial resources within the organization.

Key findings

Pros

Larger spans of control facilitate the leveraging of managerial talent to more workers.

More knowledgeable workers can work more autonomously and therefore need less managerial time, allowing managers to supervise more workers.

Performance evaluation facilitates learning about workers’ ability and makes the allocation of talent within the firm more efficient.

Product market competition leads to flatter organizations and makes firms more responsive to their changing environment.

New technologies improve communication and information acquisition and allow managers to supervise more workers.

Cons

Higher spans of control limit the attention that managers can allocate to each worker, diluting the transmission of talent.

The reduction in the number of layers limits promotion opportunities and can lead to an increase in wage inequality within the firm.

The highest performers do not necessarily make the best managers, as leadership skills may differ from task-specific skills.

Loss of control associated with reducing the number of layers might affect the quality of decision-making.

Learning takes time, and lack of knowledge about individual managerial ability can lead to short-term misallocation of talent.

Author's main message

How to efficiently allocate managerial talent within an organization is of tremendous importance for the modern firm. Assigning more workers to a manager helps to leverage the manager’s talent but also limits the amount of attention the manager can devote to each worker. Modern information and communication technologies can assist managers to supervise more workers and also make workers more knowledgeable. Product market competition also makes firms adopt flatter organizational structures as they try to respond more quickly to a rapidly changing competitive environment.

Motivation

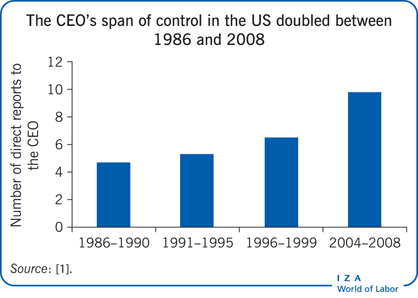

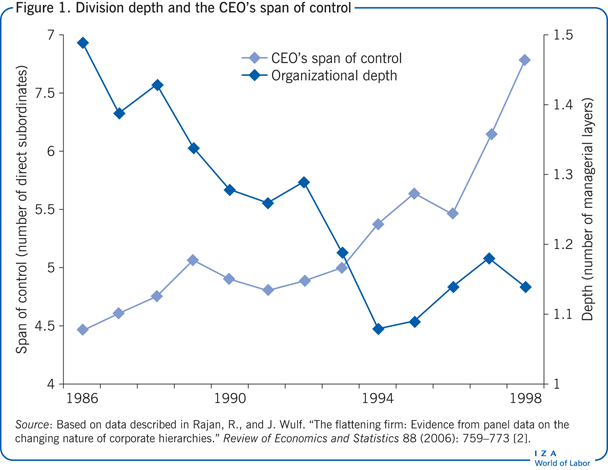

The organization of firms and the nature of managerial work have changed dramatically over the last 30 years. Firms have adopted flatter organizational models, leading to a reduction in the number of hierarchical layers, the delegation of authority lower in the organization, and a decrease in the layers of middle managers. The adoption of flatter organizational models has also led to an increase in the span of control, that is the number of subordinates that managers directly control. A survey of a sample of Fortune 500 firms reveals that the CEO’s span of control has increased dramatically, rising from 4.5 direct subordinates in the mid-1980s to 6.8 in 1998, while the number of layers between the CEO and divisional managers has been cut by nearly 25% (Figure 1) [2]. More recent data indicate that the CEO’s span of control had risen to around ten direct subordinates by the mid-2000s (see Illustration) [1]. Firms are therefore overseeing more employees with fewer managers, and evidence from the business press seems to indicate that this trend is on the rise.

Discussion of pros and cons

Allocating talent within firms

Leveraging managerial ability

The firm’s choice of organizational structure is widely accepted to be tremendously important as it determines the allocation of managerial talent within the firm. The choice of organizational structure involves several interrelated decisions: (i) how to allocate managers within hierarchical layers; (ii) how to allocate managers between layers; and (iii) how to determine the optimal number of layers.

Within a given hierarchical layer, the debate on the optimal span of control centers on the following trade-off: a larger span of control helps good managers leverage their ability over more workers, but at the cost of decreasing the attention they can devote to each worker. The quality of management matters because the decisions made at the top affect the work of people at lower levels of the firm, so that talent is diffused from the top to the bottom of the hierarchy. A higher span of control facilitates the diffusion of talent to more workers, so it is expected to be associated with higher productivity. However, managerial time is a scarce resource, so a higher span of control also means that managers have less time available for each worker, therefore diluting the transmission of talent. There are diminishing returns to managerial ability.

Diversity of work practices

When deciding on the span of control, firms try to find the right balance between these two forces. Therefore, depending on the nature of the work performed by workers and the environment that the firm faces, there is substantial variation in the span of control between firms and within them. A case study of a large Scandinavian high-tech manufacturing firm indicates that within-firm variation can be dramatic [3]. At this firm, managers at the same hierarchical level supervise an average of 25–30 employees, but the number varies from 1 to 286 subordinates. Within a hierarchical layer, managers with more human capital, such as higher levels of education or more years of experience in the firm, manage more workers, suggesting that more able managers command more resources [4]. There is also variation across layers. Individuals at higher hierarchical levels tend to have better schooling, more experience, and longer firm tenure [4]. The firm has strong incentives to assign more talented individuals higher up in the hierarchy, since talent matters more at the top. Finally, the span of control decreases when moving up the hierarchy, with middle managers supervising fewer direct subordinates than managers below them [4]. Managerial tasks are more complex at the top than at the bottom.

In determining the number of layers, firm size is definitely a key factor. Larger firms have a larger pool of workers to supervise, and they deal with more complex tasks than smaller firms. Larger firms may therefore need more layers to achieve coordination between the various activities of the firm. Two studies, one on Italian metalworking plants [5] and the other on French manufacturing firms [6], show that firm size plays an important role in shaping a firm’s organization. Accordingly, larger firms have more managerial layers, their managers supervise more workers, and decisions are less centralized than in smaller firms. Organizational changes also seem to vary by firm size, as hierarchy flattening and span increases occurred mostly in large and medium-size firms [5].

The diversity of work practices within and between firms highlights the fact that applying a universal policy may be misleading. The span decision will typically depend on factors such as task complexity, the degree of standardization, managerial quality and experience, and the need for interaction. Many of these factors are hard to measure.

Hierarchical organization of knowledge

Firms use hierarchies to organize knowledge optimally and to solve coordination problems. Hierarchies can help firms to partition workers’ knowledge: workers focus on different tasks along the hierarchy, and each task requires a different knowledge set. Hierarchies enable managers to specialize. The efficient allocation of knowledge within a firm will depend on the expertise of managers, the knowledge of workers, and the transfer of knowledge within the organization. Not only should firms allocate the best managers to the top of their organization, they should also allocate the more knowledgeable subordinates to the best managers. Knowledge is better leveraged when a manager works with smarter subordinates. Finally, if knowledge is easier to transfer or to communicate, managers will tend to have larger teams, as it is easier for managers to transmit their knowledge to their subordinates.

This partitioning of knowledge is extremely valuable in human capital-intensive industries, where returns to knowledge specialization are high. Legal services fall in this category. The internal organization of law firms has been the subject of several studies [7], [8], [9]. Law firms are often organized as partnerships in which partners manage associates. Partners and associates usually match on the quality of the law school they attended, suggesting that positive sorting by cognitive ability is important [7]. Another interesting feature of legal services is that while many lawyers specialize, some choose to practice general law. A factor that seems to drive specialization is local demand. Strong local demand leads lawyers to knowledge specialize and partners to increase their span of control. Furthermore, large market size may make specialization more attractive as returns to managerial expertise increase [8].

Span of control, responsibility, and wages

Span of control, responsibility, and wages are intrinsically related. Studies using data from European and US firms find that managers who supervise more subordinates or have more responsibility earn higher wages [3], [4], [10]. Managers higher up in the hierarchy are also paid higher wages. In the context of legal services, wages of associates and partners are positively related, indicating that higher paid partners will work with higher paid associates [9]. Firms reward talent, especially if talent is highly leveraged.

Learning about talent inside firms and career dynamics

One aspect that has been largely overlooked in the literature is that firms usually attempt to learn about workers’ managerial ability by observing their performance over time. This process can take time and may generate some inefficiencies. As a firm accumulates more knowledge about its workers, it can more efficiently assign managerial talent within the firm. However, this process may lead to misallocation in the short term as it might be difficult to judge workers’ potential early in their employment tenure. This explains, for instance, why firms put so much emphasis on performance and talent management.

The process of performance and talent management also implies that, in practice, workers will be reallocated over time along the hierarchy and their careers evolve as a consequence of the learning process about their managerial ability. The case study of the large Scandinavian high-tech manufacturing firm mentioned previously suggests that individuals with higher levels of performance are allocated larger spans of control and are more likely to be promoted [4]. Workers with consistently high performance are assigned more responsibility and climb the career ladder. Span of control and hierarchical level therefore reflect what firms have learned about their employees. Also important, the learning process provides incentives to work hard by offering promotion opportunities. However, efficiently allocating managerial talent while also providing incentives through promotions can be tricky. This is especially a concern in the case of workers who have the ability to perform a specific task as opposed to having leadership talent. When a firm values both types of talent, it can justify the use of a dual-track system in which talented professionals who might not have strong leadership skills, and so are not allocated to managerial positions, still receive a promotion in title and higher wages. Such a policy was, for example, observed in the case of the large Scandinavian high-tech firm [3], [4]. Dual-track systems provide career incentives and retain valuable human capital, without necessarily misassigning workers to leadership positions for which they lack the necessary skills.

The studies mentioned above suggest that better managers have larger spans of control. The top of the hierarchy would therefore be expected to exhibit a similar pattern, and more able CEOs would be expected to have a larger span of control. However, the evidence seems to contradict this claim. A study of Fortune 500 firms finds that newly hired CEOs, in fact, tend to have a higher span of control than experienced CEOs [11]. If one believes that new CEOs are less able at managing people or lack skills that more senior CEOs possess, this result may look puzzling. The study attributes this apparent contradiction to the fact that newly appointed CEOs need a large executive team because it helps them to learn about the firm, its strategy, and how to run the business effectively. If those varying skills need to be passed on to the new CEO, it would be effective to allocate a large team of experts who can support the new CEO during the learning period. As CEOs gain experience, they reduce the size of their team, alter its composition, and delegate more decisions. This evolution suggests that learning to become a good CEO takes time and that the partitioning of knowledge across an organization may not always be vertically specialized.

Information and communication technology and the flattening of the firm

Among the key factors that have contributed to the management delayering and flattening of firms, almost all commentators agree that a crucial determinant has been the information and communication technology revolution. It facilitated communication and the transfer of information between layers and more generally within the organization, thereby increasing the leveraging of managerial ability and making intermediate middle management layers less relevant. However, the different types of information and communication technology do not always lead to the same effect on organizational structure.

Information and communication improvements come from the adoption of either new information technology or from better communication technology. Improvements in information technology may come from the adoption of advanced manufacturing technologies, such as computer-aided design, computer-aided manufacturing, or flexible manufacturing, or from the use of business process management software such as enterprise resource planning systems. Production-improving technologies embody production workers with more knowledge as they deal with more tasks, while enterprise resource planning technologies improve information related to non-production decisions. This increase in worker’s empowerment makes it possible for managers to oversee more workers, leading to an increase in the span of control. Communication technologies on the other hand, such as intranets and inter-firm networks, aim at facilitating communication within the firm and between the firm and suppliers and customers. When communication between managers and subordinates is easier, managers can (again) supervise a larger number of workers. In addition, workers may substitute knowledge for directions from their manager. Relying more on managers for decision-making will therefore favor centralization within the firm.

A few studies have focused on the link between information and communication technology and organization in different contexts: metalworking plants in Italy at the end of the 1990s [12], US and European firms at the end of the 2000s [13], and Fortune 500 firms from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s [2].

These pieces of evidence indicate that the adoption of better information technology, such as advanced manufacturing technology and enterprise resource planning, has been associated with a lower number of hierarchical layers, an increase in managers’ span of control, and an increase in the autonomy of workers and of lower-level managers [12], [13]. Improvements in information technology flatten firms and move decision-making down toward the bottom of the hierarchy. Managers’ span of control is larger because managers can supervise more knowledgeable workers.

Technologies facilitating communication within the firm, like an intranet, have been associated with more hierarchical layers and less autonomy in the lower part of the hierarchy [12], [13]. Communication improvements appear to have deepened the organizational structure of firms, as knowledge became easier to transfer from the top to the bottom. On the other side, firms adopting technologies facilitating communication with outsiders, like suppliers or customers, had a flatter hierarchy, which could be related to the fact that those technologies make outsourcing less costly.

Finally, changes in technologies also affect the composition of the executive team. The observed increase in CEOs’ span of control since the mid-1980s has been associated with an increase in the number of functional managers reporting directly to the CEO. This increase occurred mainly in firms that improved their information and communication technology and affected functional managers in administrative or back-end activities, like finance or human resources. Information and communication technology may be especially useful when synergies can be exploited between business units, which is the case in administrative or back-end functions [1].

Competition and trade liberalization

Since the 1990s, the macroeconomic environment that firms are facing has changed dramatically. Product market competition has intensified, both internationally and domestically, following the dismantling of trade barriers, the deepening of trade liberalization, and deregulation. Greater competition may force firms to alter their organization. Firms flatten their hierarchy to more efficiently manage knowledge and decision-making. Firms may also reduce their product scope by refocusing on their core competence, which in turn affects the way they are organized. Finally, firms may reorganize to cut costs, especially labor costs, by getting rid of excessive layers and workers.

In 1989, the US and Canada signed a free-trade agreement to eliminate tariffs and trade barriers between the two countries. A study of more than 300 publicly traded US firms before and after this agreement helps to better understand the impact of trade liberalization and product market competition on firms’ organization [11]. Accordingly, when facing more competition, firms tend to flatten: they reduce the number of managerial layers and increase the size of the executive team (or the CEO’s span of control). Following the implementation of the free-trade agreement, firms experienced an average 6% increase in CEO span of control and an average 11% decrease in the number of layers. Some firms were more exposed to trade liberalization than others, and the intensity of these effects varied according to the increase in competition faced by a given firm, with greater exposure leading to larger changes. As a consequence, firms that were more exposed to trade liberalization also exhibited a decrease in firm diversification and product scope and a change in decision-making allocation, suggesting that those mechanisms explain the observed flattening of firms.

Reorganization and firm growth

When firms expand or contract their activities, reorganization is often necessary. Firms may adjust their organization by adding or removing layers, by expanding or reducing the span of control of their managers, or by adjusting the composition of their workforce. Those changes will not only affect the firm’s structure, but also lead to changes in workers’ compensation, recruitment and promotion policies, and in the skills or knowledge embedded in the workforce.

A recent study, using a large institutional data set of French manufacturing firms, investigated how firm growth affects firms’ reorganization [6]. The study documents that transitions between layers are common. The decision to add layers is positively associated with the value created by the firm; the decision to remove layers has the opposite effect.

The study also highlights another interesting fact: when firms grow, they can choose from two possible alternative paths, that is either grow by adding new layers to their organization or grow by increasing their workforce proportionally across all existing layers. Firms that expand by adding layers behave differently from firms that expand without reorganization.

Firms that expand without reorganization add more workers to all layers, adding proportionally more at the bottom, which leads to a flattening of their hierarchy. Workers’ knowledge increases as firms hire workers with more human capital, especially at the bottom. The leverage of managerial expertise therefore increases in each layer, and firms reward their employees accordingly with higher wages across all layers.

Firms that reorganize exhibit a different pattern. In this case, growing firms reorganize by reallocating their more knowledgeable and highest-paid workers to the top and by hiring new, less knowledgeable and lower-paid workers at the bottom. As a consequence, the average wage in lower layers decreases. While this may seem counterintuitive, the reason behind this finding lies in changes in the composition of employees within layers rather than in changes in individual wages. Knowledge is moved to the top, so that high-level managers better leverage their expertise and knowledge.

Thus, the type of growth that firms choose will affect their organization. It will also affect their management practices, as knowledge, compensation, recruitment, and promotions will need to be adjusted. Understanding how firms need to reorganize is key to efficiently managing firm growth.

Limitations and gaps

A clear difficulty in the literature is the lack of sources of information about the span of control and firms’ organizational charts. Researchers have to make creative use of compensation surveys on top executives or administrative data not necessarily designed to study those questions. Some have used information taken from detailed personnel records of individual firms, but it is not clear how their results can be generalized. A more convincing approach is to ask firms directly about their organizational structure in a survey designed for this purpose. But even then, firms may be reluctant to disclose potentially sensitive information, and the way they are organized can be complex to summarize.

Another challenge is that many factors that influence the span of control and firms’ organizational structure can be subjective or difficult to evaluate. For example, task complexity, task divisibility, information flows, and the need for interaction are extremely hard to measure. As a consequence, there is a lack of systematic evidence on the determinants of span of control.

Among the questions that remain unanswered from an empirical perspective, two appear to be particularly important: (i) the role of internationalization and offshoring; and (ii) the effect of organization on productivity.

The link between the span of control and outsourcing/offshoring does not appear to have been thoroughly investigated, even though it may be mentioned in a few studies. Information and communication technologies ease communication within the firm but also between the firm and suppliers, changing the make-or-buy decision for various activities, with obvious implications for organizational structure. Information and communication technologies also improve the coordination of activities that take place within the boundaries of the firm but possibly in a foreign subsidiary. Very little is known about the internal organization of multinational companies and how domestic and international outsourcing affect them.

Similarly, there is almost no evidence on the consequences of organizational structure for productivity. Large firms reorganize their activities on a regular basis, leading to dramatic re-drawings of the organizational chart. The top management team makes these decisions to improve firm performance, but there does not appear to be any consistent evidence regarding the efficiency of these changes.

Summary and policy advice

Properly designing the firm’s hierarchy and allocating scarce managerial resources within the organization have important implications for the efficiency of supervising workers, sharing knowledge, and coordinating tasks. However, there is no universal recipe for the optimal span of control since each firm has to fine-tune its internal organization to the task specificities and the level of complexity associated with various managerial decisions, as well as to the external environment and the strategy chosen. The information and communication revolution has clearly affected organizational structure by facilitating information acquisition and communication throughout the hierarchy. At the same time, increased product market competition has made organizations flatter as firms have tried to adapt more quickly to a more volatile environment.

There are several lessons to be taken from the findings described in this article. First, while flatter organizations clearly have advantages, firms also have to be careful not to overextend their managers, which might have adverse consequences for the quality of supervision and task coordination. Flatter organizations can also reduce career incentives by making promotions harder and less frequent. Second, training programs that increase workers’ knowledge save on managerial resources and enable managers to supervise more workers. Moreover, matching managers and workers’ skills appropriately can generate efficiency gains. Third, talent programs that help firms identify leaders improve the learning process and make the allocation of managerial talent more efficient. Fourth, changes in the hierarchical structure have important implications for within-firm wage inequality and, by extension, for aggregate wage inequality.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Valerie Smeets