Elevator pitch

Cash transfers are a popular and successful means of tackling household vulnerability and promoting human capital investment. They can also reduce child labor, especially when it is a response to household vulnerability. But if not properly designed, cash transfers that promote children’s education can increase their economic activities in order to pay the additional costs of schooling. The efficacy of cash transfers may also be reduced if the transfers enable investment in productive assets that boost the returns to child labor. The impact of cash transfers must thus be assessed as part of the entire social protection system.

Key findings

Pros

Cash transfers can reduce the economic vulnerability of households and increase human capital investment, especially in low-income countries with weak social protection systems.

Cash transfer programs have proven to be valuable in reducing child labor that arises as a response to household vulnerability.

Adding interventions to reduce the costs of school and health care and improve their quality can increase the effectiveness of cash transfers in reducing child labor.

Cons

If invested in productive assets, cash transfers can increase household demand for child labor.

If cash transfers enable children to enroll in school, child labor might increase to support additional education costs.

Few cash transfer programs have reducing child labor as a primary objective.

In most cases, increases in school attendance are not fully matched by reductions in child labor.

Author's main message

Evidence shows that cash transfers can address child labor by reducing household vulnerability, but there is considerable variation in impact. Differences in program design are one reason. Another is that the effects on child labor may be dampened by the need to pay additional costs if the transfers enable children to go to school. There may also be incentives for increased child labor if transfers invested in productive assets increase the returns to children’s work. Thus, adding interventions to reduce the costs and improve the quality of school and health care are a promising complement to cash transfer programs.

Motivation

Social protection policies such as cash transfers seem to be an obvious way to reduce child labor. Cash transfers aim to relieve household economic hardship by providing income support. By easing the economic vulnerability of households, cash transfers can remove some of the reasons that children work. Cash transfer benefits are often coupled with incentives for behavioral change, as in the case of conditional cash transfers that include conditions for children’s education or health care.

Cash transfers can have complex effects on household behavior that go beyond easing budget constraints. For example, if cash transfers change the relative prices of children’s time use (in work and schooling), that may affect a household’s decision to send a child to school. School attendance requires the commitment of a certain amount of a child’s time and incurs some fixed costs, which are likely to change the financial constraints facing the household. Also, the household might use part of the transfer for investments in productive assets instrumental to farming or small business activities, such as fertilizer, plows, or sewing machines, which can make it more profitable for children to work. Both of these mechanisms make the effect of cash transfer programs on child labor uncertain.

This paper discusses some of the potential benefits and limitations of cash transfers for vulnerable households, drawing on extensive evidence from impact evaluations. While this does not exhaust the evidence on this topic, focusing on impact evaluations means relying on statistically solid information generated by actual cash transfer programs. Also, there are limits to what cash transfers and, more generally, social protection programs can do to reduce child labor. Access to and the quality of education, returns to education, and access to good jobs after graduation are a few of the variables that also shape household decisions affecting children’s work.

Discussion of pros and cons

Defining child labor

Child labor (a subset of child work that is not allowed according to national and/or international regulations) is a legal rather than a statistical concept. Translating broad legal norms established in international agreements into statistical terms for measurement purposes is not straightforward. The international legal standards contain a number of flexibility clauses that are left to the discretion of national authorities. Hence there is no global legal definition and is no standard statistical measure of child labor.

Consequently, the terminology and concepts used to categorize children’s work and child labor (and to distinguish between the two) are at times inconsistent in published studies [1]. Similarly, there is substantial variation in the productive activities covered by the studies considered here. Some focus on specific activities (such as work in agriculture), whereas others use a broader definition of work (such as work in economic activities). There is also variation in reference periods. Finally, some studies focus on how many children work and some on how much children work.

Household vulnerability and child labor

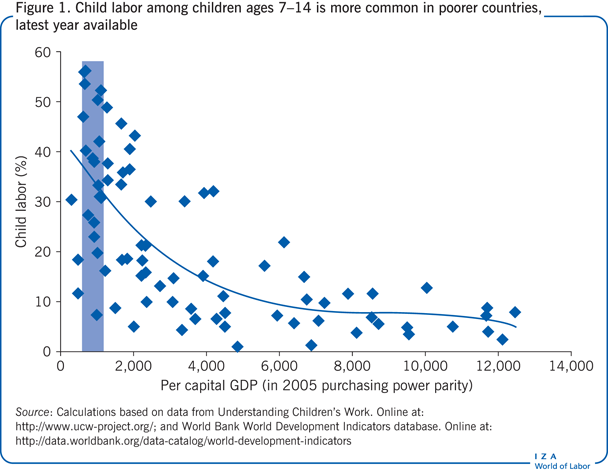

By the latest International Labour Organization estimates, more than 120 million children aged 5–14 were engaged in labor in 2012; this is about 10% of children in this age group. There are many causes of child labor, with household economic vulnerability being the principal one [2]. Poor households with inadequate resources and no access to credit markets are likely to make inefficiently low investments in their children’s education and to let their children work at an early age. Lack of access to financial and insurance markets also makes households more vulnerable to the effects of income losses. One of the coping strategies is to withdraw children from school and send them to work.

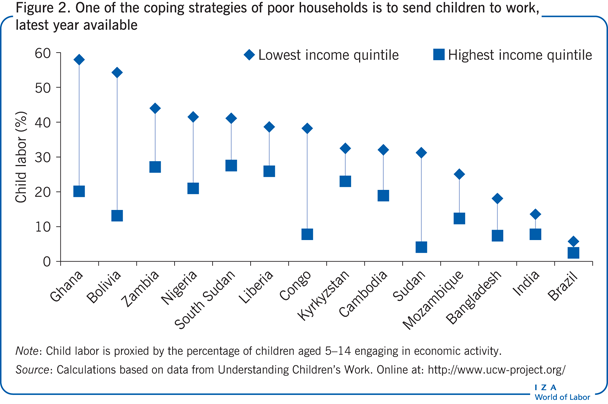

Two figures illustrate these points both across and within countries. Figure 1 presents correlations between income per capita and child labor for children ages 7–14 (as proxied by participation in economic activities) for a large group of countries. Figure 2 presents the difference in the incidence of child labor across five income groups (quintiles) in selected countries. Both across and within countries, the link between poverty and child labor emerges clearly. Countries with higher GDP per capita tend to have a lower incidence of child labor (Figure 1), while within countries children in the poorest households engage in economic activities at a substantially higher rate than children in higher income groups (Figure 2). It is also clear, however, that poverty is not the only cause of child labor, as illustrated by the high variation in the incidence of child labor for similar income levels across countries, and by some incidence of child labor even in the top part of the income distribution within countries.

Social protection policies are thus an obvious potential means of addressing some of the factors driving child labor. By alleviating the economic vulnerability of households, social protection policies may remove some of the reasons that families send their children to work.

Transfers to families with children

Transfer programs aim to relieve economic vulnerability by increasing household income. The cash transfers are often accompanied by certain behavioral requirements, or conditions (conditional cash transfer programs). For example, some conditional cash transfer programs require that beneficiaries send their children to school or take them regularly to health clinics.

Cash transfers can have complex effects on household behavior through two mechanisms. They can affect child labor by modifying children’s likelihood of attending school or by changing the returns to child labor [3]. First, cash transfers may change how households value children’s use of time, encouraging them to send children to school and thus to work less or not at all. However, school attendance requires the commitment of a set amount of a child’s time and also increases household spending on education [3]. Thus, deciding to send a child to school is likely to affect the household budget (more costs for school and less income from child labor). Second, if the household uses part of the cash transfer to invest in assets that make child work more productive (and thus more profitable), the transfer could increase the value of children’s work to the household. Both these mechanisms make the likely effect of cash transfer programs on child labor uncertain.

Because school attendance generally requires a fixed minimum time investment (it is not usually possible to choose the number of hours a child will spend in school), a child who begins to attend school following a cash transfer will have less time for leisure and work. Moreover, the household faces some fixed costs to send a child to school (school fees, uniform, travel costs). The final impact on child labor depends on whether the amount of the cash transfer exceeds the cost of attending school. If the transfer falls short of the monetary cost of sending a child to school, the resulting change in child labor is ambiguous because both consumption and leisure would be reduced by sending a child to school. If the transfer exceeds the cost of sending the child to school, then consumption can also increase and child labor should decrease as the household can improve its condition without relying on the child’s earnings.

This conclusion holds only if the household uses the cash transfer to finance consumption or education. However, because money can be spent in many different ways, the additional resources could be used instead to invest in productive assets. Such investments could increase the returns to child work directly if the child works in the household business or farm and productivity in these activities increases as a result of the investment. They could also increase the returns to child work indirectly, through changes in the adult labor supply—for example, if household members devote more time to productive activities and less time to household chores, children’s time will become more valuable in household chores. While there is evidence that cash transfers are used in this way, to invest in productive assets, there has been only limited analysis of the consequences of this choice for child labor (see, for example, [4], [5], [6], [7] and the literature cited therein).

The impact of cash transfers on child labor

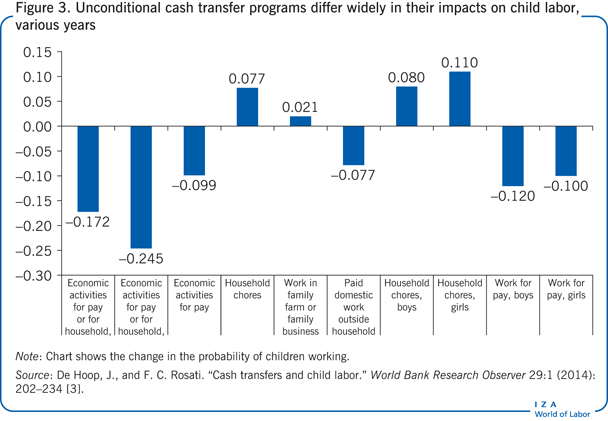

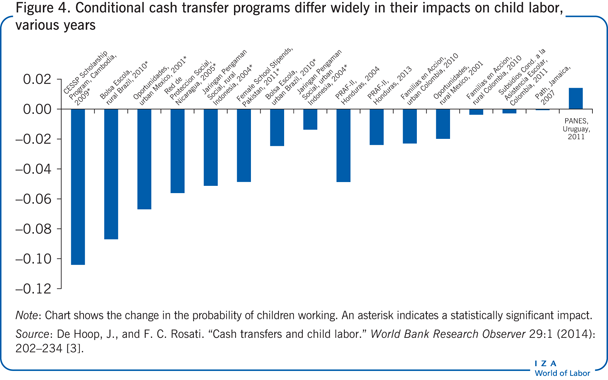

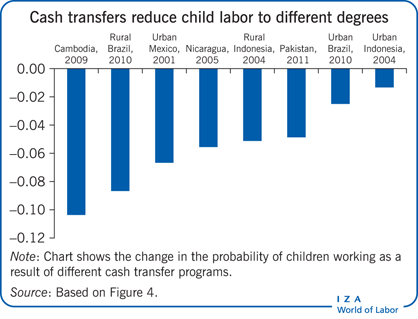

In general, impact evaluations find that both unconditional and conditional cash transfers can reduce child labor (Figure 3 and Figure 4). There are, however, large variations in the effects of different cash transfer programs, and for several programs, no significant impact could be identified.

It is not easy to identify the factors that are associated with the observed differences in the impact of cash transfer programs on child labor. A large part of the variability could be due to program characteristics that are difficult to capture in a comparative analysis. Nonetheless, some general points can be derived from the analysis that could inform program design so as to make cash transfers more effective in reducing child labor.

First, the impact on child labor does not precisely mirror the increase in school attendance generated by cash transfer programs: the increase in school attendance is generally much greater than the reduction in child labor. Within the set of conditional cash transfer programs considered in Figure 4, a one percentage point increase in school attendance is accompanied by only a 0.3 percentage point reduction in children’s work [3]. This is not surprising, since school and work are not mutually exclusive (for example, children can work after school or during school holidays, or miss some classes for work). Nonetheless, working while attending school is potentially detrimental to educational achievement and grade completion.

There are other reasons why increases in school attendance are not fully matched by reductions in child work. A key reason is that cash transfers can increase household investment in productive assets used in economic activities, such as in farming and small businesses. While there has been little direct examination of the impact of this mechanism on child labor [7], impact evaluations of microcredit programs find that households’ increased involvement in productive activities can lead to increases in child labor, as has been the case with microcredit programs in Bosnia, Thailand, and Bangladesh [8], [9], [10].

A second important point is that additional resources beyond the amount of the cash transfers might be needed to help households pay for the increased costs associated with sending a child to school. Without such additional resources, children who were working and begin to attend school might not stop working, or children who begin to attend school might also begin to work to help the household meet the additional expenses. Evidence of these types of effects have been found for the Bright program in Burkina Faso (designed to improve access to quality education for girls) and the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) in the Philippines (a conditional cash transfer program to eradicate extreme poverty by investing in children’s health and education). In both programs, school attendance increased but was not associated with a reduction in child labor. In fact, involvement in child labor increased, especially among children who began to attend school following household participation in the program.

The impacts of conditional cash transfer schemes

Conditions were introduced to transfer schemes with the intention of improving their effectiveness and ensuring that the benefits were used, at least in part, to improve children’s human capital. Common conditions in cash transfer programs require that participating households send their children to school regularly and take them in for regular health checks. Conditions have not addressed child labor participation because reducing child labor has not been a direct objective of most cash transfer programs (although participation of children in work has been a criterion for identifying households to receive benefits).

There are obvious reasons why conditions have not been imposed on child work. For instance, school and health clinic attendance are easy to monitor using school or clinic records. Objective verification of child work, by contrast, would be very difficult since most children who work are engaged in family businesses or in the informal sector, often in violation of national law. Monitoring would have to rely on statements by parents and children, which could be unreliable in these circumstances.

While evidence suggests that conditional cash transfers have a stronger impact on school participation than unconditional cash transfers do, whether the conditions related to child education reduce child labor has been much more difficult to assess. First, the decision to include an education condition in a program might depend on the expected impact of the program on the target population (meaning that the condition is endogenous, making assessment of impact difficult). Most studies do not specify the precise conditions attached to the delivery of the services or provide information on the degree of enforcement of the conditions, thus making straight comparisons of effectiveness difficult.

A few studies, however, offer some evidence in this area [11], [12]. The studies use variations in implementation of Ecuador’s Bono de Desarrollo Humano cash transfer program that, according to official reports, led some participating households to believe incorrectly that the cash transfers were conditional on children’s school attendance. The effect of the program on child labor was similar in households that believed that the program was conditional on school participation and in households that did not [3]. In both groups of households, child labor decreased.

Recent discussions of cash transfer programs have focused on whether conditions make a difference in the effectiveness of the programs or whether other approaches could achieve better results. One study of the Tayssir program in Morocco examined whether a cash transfer program open to all poor households without conditions could be as effective in increasing school enrollment as traditional targeted and conditional programs. Enrollment for the unconditional program was school-based, thus conferring an implicit endorsement of education. The study asked whether “a ‘nudge’ may be sufficient to significantly increase human capital investment, while [conditional cash transfer programs] as currently designed provide a big shove” [13]. The results show that a rural cash transfer program simply “labeled” as supporting education had a large impact on school participation even though the transfer was not conditional on school attendance. This has relevance for the case of child labor, where imposing explicit conditions might not be feasible.

Integrating cash transfer programs with other interventions

The impacts of cash transfer programs on child labor appear to be greater when cash transfers are complemented by interventions that reduce the costs of health care and education services or improve their quality [1]. Some other cash transfer programs have focused on both safety net provision and active poverty reduction by including support for household income-generating activities through grants or loans to buy investment goods. These programs seem to have a smaller impact on child labor, confirming that interventions that increase household economic activity tend to generate greater demand for children’s work.

Limitations and gaps

Cash transfer programs seldom have the reduction of child labor as a primary objective, and so impact evaluations rarely assess this outcome in depth. As a result, little is known about which program characteristics affect child labor. The role of the design elements that have been tested appears to be limited. There is little evidence that conditions that mandate that children attend school affect the programs’ impact on child labor. The size of the transfer relative to household income also appears to have little influence in reducing child labor. Some conditional cash transfer programs that transfer substantial sums of money have had no effect on child labor, whereas other programs that provide only a small subsidy have resulted in large changes.

Another key issue concerns measurement of child labor. Only a few studies have examined the extent to which cash transfers prevent and reduce the worst forms of child labor, including hazardous work and long working hours, which can interfere with learning in school. Similarly, cash transfer programs appear to be more effective in reducing child work in economic activities, typically engaged in by boys, than in household chores, typically engaged in by girls. However, studies that look at impacts on child labor tend to focus solely on children’s economic activities. Few studies have documented changes in household chores as a result of cash transfer programs, thus underreporting the effects of programs on girls. This is an important oversight as many girls can be attending school while burdened by a heavy load of household tasks, compromising learning and leading to early drop out.

Vulnerability is not the only cause of child labor, and therefore social protection policies such as income transfers are not the only relevant policies for reducing child labor. Poor access to education, low returns to education, and high demand for unskilled labor are other possible reasons for child labor. Therefore, policies aimed at addressing constraints to human capital investment are also relevant for addressing child labor.

Because cash transfer programs are generally part of broader social protection systems that include other components, ranging from health insurance to other targeted transfers or subsidies, their full potential can be determined only by evaluating them in the context of those broader social protection systems. Moreover, the source of financing is seldom considered in discussions of the effectiveness of cash transfer programs, but that is clearly relevant in determining their effects on child labor and other outcomes. Most studies assume, mainly implicitly, that funding is made available from outside the system and that changes in revenue or debt necessary to finance the program do not affect the target population. While this might be the case for small pilot programs, it cannot be so for large programs (like Mexico’s Prospera I and Brazil’s Bolsa Familia). In short, while impact evaluations provide a sense of the changes induced at the margin by a cash transfer program, any full assessment of their effectiveness requires consideration of the program’s source of financing and its integration with the rest of the social protection system, which has not yet been done.

Finally, while the results discussed here can improve the effectiveness of cash transfer programs, the main problem facing vulnerable households is the lack of scale of many social protection interventions, especially those targeting families with children.

Summary and policy advice

Cash transfer programs have the ability to reduce child labor, especially in low-income countries and in countries where social protection systems are weak. Providing a safety net to vulnerable households that lack access to capital markets reduces their use of child work as a coping mechanism.

Evidence from impact evaluations shows that cash transfers are especially relevant if well targeted to the most vulnerable households whose children are at risk of missing school or working. For programs that address large numbers of households with children who are not working, the effects are more diluted.

There are also theoretical reasons, supported by some evidence, pointing to a smaller impact of cash transfer programs on child labor through schooling. The need to finance additional education expenditures, as well as the increased returns to child work when transfers are used to invest in productive assets, might dampen the effects of these programs.

Additional elements could be incorporated in cash transfer programs to deal with these problems and make them more effective. While adding conditions on child labor does not appear feasible, adding measures that reduce the costs of school and health care and improve their quality looks like a promising approach. Adjusting the level of transfers, especially through scholarships, might also be needed to ensure that households can afford the additional costs of sending children to school.

More complex is the problem of the increase in the returns to child work due to investments in household productive activities. Public information campaigns could provide households with information on the risks of children’s early involvement in work and on the real return to education (including to the family business). In middle-income countries, cash transfer programs could, for instance, be complemented with services to help youth find profitable employment after graduation, thus increasing the expected returns to education.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [3].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Furio C. Rosati

The three principal international agreements on child labor

The legal boundaries of child labor and the legal basis for national and international actions against it are established by three principal international conventions on child labor: International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 138 on minimum age; the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child; and ILO Convention No. 182 on the worst forms of child labor.