Elevator pitch

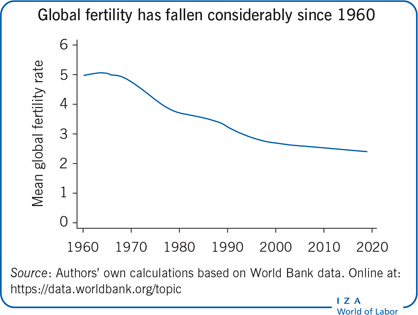

At the national level, it has long been observed that a country's average education level is negatively associated with its total fertility rate. At the household level, it has also been well documented that children's education is negatively associated with the number of children in the family. Do these observations imply a causal relationship between the number of children and the average education level (the quantity–quality trade-off)? A clear answer to this question will help both policymakers and researchers evaluate the total benefit of family planning policies, both policies to lower fertility and policies to boost it.

Key findings

Pros

Lower fertility, or fewer children per family, is associated with more years of schooling.

Smaller families can invest more in each child, which boosts measures of child quality such as health, education, and cognitive ability.

A planned increase in a family’s number of children has less impact on per child expenditures than an unplanned increase because parents can adjust their finances in anticipation of having another child.

In developing countries, family planning policies could raise child quality.

In developed countries with very low fertility rates, pro-fertility policies may not negatively affect quality.

Cons

Negative correlations between the number and quality of children might reflect a spurious relationship.

The average cost of raising children is higher for smaller families as they cannot take advantage of economies of scale, such as sharing of rooms or clothes.

An unplanned increase in the number of children might have a strong negative effect on child quality.

Policies to reduce fertility in order to enhance child quality might not be effective when education is heavily subsidized and the school leaving age is regulated.

Author's main message

Policies aimed at reducing fertility will likely increase parents’ education spending per child, particularly in developing countries that need to curb rapid population growth rates. However, while policies that encourage couples to have fewer children could stimulate parental investment in children's health and education, empirical studies find that the impact is likely to be small. In developed countries, where the policy concern is more likely to be low (below-replacement) fertility rates, policies to encourage families to have more children are unlikely to affect child quality negatively.

Motivation

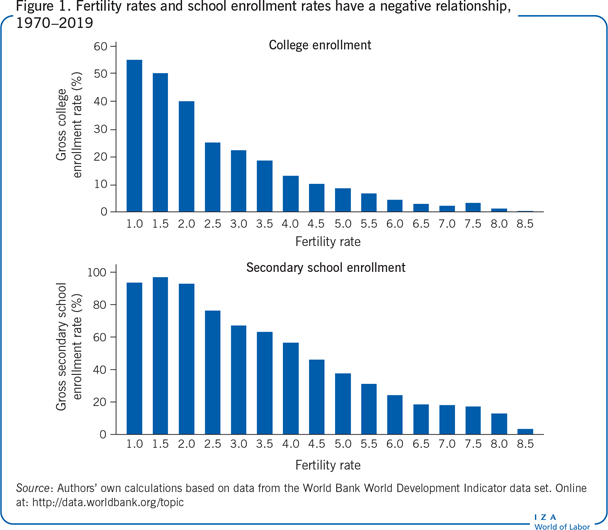

Both college and secondary school enrollment rates are strongly and negatively correlated with fertility rates (Figure 1). For instance, Niger, with the highest fertility rate (7.0) in 2017, had a gross college enrollment rate of only 3.7% and a secondary school enrollment rate of just 24.3%. South Korea, with the lowest fertility rate (1.0), had a gross college enrollment rate of 94.3% and a secondary school enrollment rate of 100%. The correlation coefficient—the degree to which changes in the value of one variable predict changes in another, with values from -1 to +1—between fertility and enrollment was –0.71 for college enrollment and -0.79 for secondary school enrollment in 2017. The question that naturally follows is does reducing the fertility rate lead automatically to higher school enrollment rates? Answering that question is not as simple as Figure 1 would suggest, because some variables affect fertility and education simultaneously.

Discussion of pros and cons

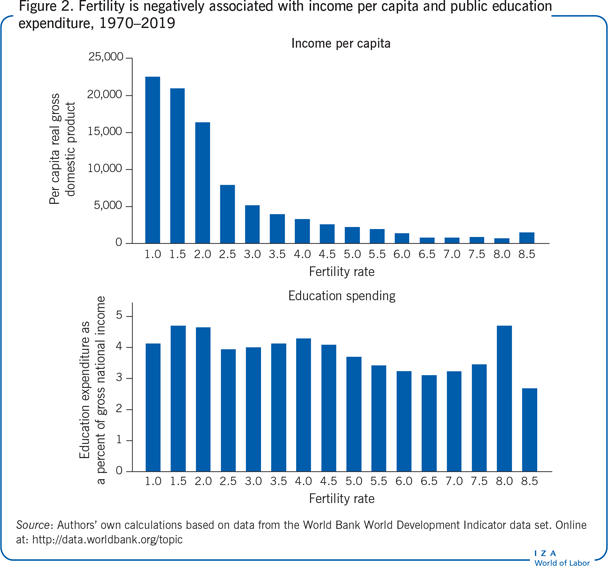

Countries with lower fertility rates tend to be more affluent, with higher per capita income (Figure 2). They spend more, both as a percentage of gross national income and in absolute dollar terms, on education than countries with higher fertility rates. So, it is not evident based on theoretical deduction whether the higher college and secondary school enrollment rates in high-income countries are driven by lower fertility or by national income, educational expenditure, or other factors, such as parental preferences.

To minimize the impact of differences in institutional settings across countries on the estimated relationship between the number of children and the quality of their human capital, most studies on this issue focus on individual-level data. However, even when the focus is on families living in the same country, the simple correlation between child quantity and quality does not necessarily imply a causal relationship. For instance, some parents might have a stronger preference than others for having highly educated children, and these parents may prefer to have fewer children as well. Consequently, the negative correlation between child quantity and quality could be due to a negative impact of quantity on quality, but it could also be due to differences in parental preferences about child quality. To address this issue, researchers have used variations in child quantity related to external factors that should not affect quality, such as the birth of twins [1], [2], the gender composition of children [3], [4], [5], and the stringency of family control policies [6], [7], [8].

Differences in developed and developing countries

As shown in Figure 2, fertility rates are higher and educational expenditures are lower in low-income (developing) countries than in high-income (developed) countries. If government spending on education is a substitute for private spending, then variations in private spending will have a limited impact on children's schooling in countries where education is heavily subsidized. Since a major reason for the quantity–quality trade-off is that an increase in the number of children reduces private education spending per child, heavy public subsidies of education will weaken the quantity–quality trade-off in developed countries.

For instance, many developed countries provide not only free (compulsory) primary education, but also free school lunches to students from poor families. As a result, the direct private costs of primary education are virtually zero or even negative. In addition to government subsidies, developed countries tend to have better functioning credit markets than developing countries, which helps children from large families finance their college education. Therefore, parental resources and the number of children will have little direct impact on child education. In contrast, in many developing countries, even if there are no tuition fees for public primary schools, parents generally have to pay for textbooks, school uniforms, and school lunches, which can constitute a considerable financial burden. Therefore, it is not surprising that studies using data for developing countries tend to find a significant quantity–quality trade-off, while the findings for studies for developed countries are less conclusive.

Using external shocks to family size to explore variation in child quantity

Birth of twins

One of the most common exogenous variables (variables that mimic random assignment) used to study family size is twin births. Presumably, twin births are mostly unanticipated, negating parents’ perceived control over their preferred family size. For instance, parents who planned to have only three children would end up with four children instead if the third birth is twins.

Studies of twin births have generally focused on the impact of having an additional unplanned child on the quality of children born before the twins rather than on all the children in the household. Twins have been excluded from analyses because they are more likely to have lower birth weights and higher death rates than singleton children, which directly affects their educational attainment. Children born after twin births have also been excluded because their education could be directly affected by the twin birth through such factors as birth spacing. Frequent births with short intervals between them, for example, are associated with low birth weight and small size for gestational age. By focusing on the impact on children born before twins, one study finds that having an additional child has a significant and negative effect on school progression (defined as years of schooling divided by age minus six years, where six is the typical age at which children begin school) in Brazil [1], while another study finds that having an additional child does not affect years of schooling (age-standardized z-score) in sub-Saharan African countries [2].

The gender composition of children

The gender composition of earlier-born children can also affect the number of children [3], [4], [5]. Many parents want to have at least one son. Consequently, they tend to have another child if their earlier-born children are all girls. For girls aged 12–17 from indigent rural households in Mexico, having an additional sibling, whether because of the gender composition of earlier-born children or the birth of twins, has no significant impact on their primary school completion or school enrollment [5]. One possible explanation for the different outcomes in Brazil and Mexico is that basic education is compulsory through a defined education level (lower secondary school, or roughly to age 17) in Mexico, while it is compulsory based on age (to age 14, or roughly through the second stage of primary school) in Brazil. Parental spending would have a weaker impact on the schooling of 15-year-old children in Mexico, who are still legally required to attend school, compared with 15-year-old children in Brazil, who are not.

A shared limitation of those earlier studies is that they do not control for children's physical endowments. Since singletons are generally heavier than their twin siblings at birth, parents might invest more in their non-twin children if investments in their children are positively correlated with children's physical endowments. The estimates analyzing outcomes of singletons only might either underestimate or overestimate the true magnitude of the quantity–quality trade-off depending on whether parental investments are positively or negatively correlated with children's endowments.

By comparing the estimated impacts on singletons and twins with and without controlling for birth weight, it is possible to calculate the lower and upper bounds for the magnitude of the quantity−quality trade-off. Using the Chinese Child Twins Survey, a study finds that parents invest more in their heavier offspring [9]. After controlling for birth weight, the study finds that an extra child significantly reduces school progression, lowers expected college enrollment, and worsens child health. The downside of adding birth weight is that it introduces more endogeneity since birth weight might be correlated with the number of children. Having more children—or too closely spaced births—may negatively affect the mother's nutritional intake and hence her child's birth weight. It turns out that the gap between singletons and twins in terms of weight and BMI narrows as they grow up in sub-Saharan African countries, suggesting that parents do not divert sources away from twins [2].

Stringency of family control policies

More recent studies have used the exogenous shocks of family control policies to family size to study the quantity–quality trade-off. Three studies have explored the variation in the stringency of China's family control policies across regions, over time, and (or) between the Han majority and ethnic minorities.

One study uses data from the 1993 wave of the China Health and Nutrition Survey and exploits the regional differences in eligibility criteria for having two children and fines on unsanctioned births [6]. The study finds that the number of children has a small effect on educational attainments measured by school enrollment, middle school graduation status, and normalized years of schooling (a ratio of one child's years of schooling to the mean schooling of children of the same age and gender).

Another study uses data from the 2005 Inter-census Survey with a special focus on the launch of the one-child policy in late 1979 which features in the tightening of the family control policy [7]. The study finds that the one-child policy instantly increases the tendency of being a single child among the individuals born around the cutoff point (October 1980, ten months after the introduction of the policy) and being a single child in the family significantly increases years of schooling.

Another study examines a family control policy introduced by the Vietnamese government in 1988, which required parents to have no more than two children [8]. Using data from the Vietnam Population and Housing Censuses and exploiting the variation in women's policy exposure across ethnicity groups and age groups, the study finds that having more than two children significantly decreases child education, measured by years of schooling and school enrollment.

Reproductive productivity

Parental reproductive capacity could potentially affect the number of children in a household, although it is hardly observable. One study exploits a genealogy of English individuals living in the 16th to the 19th centuries (during the industrial revolution) [10]. The study shows that parental fecundity, measured by the time interval between the date of marriage and the first birth, positively affects the number of siblings, and children of parents with lower fecundity are more likely to be literate and employed in skilled and high-income professions.

Evidence from developed and developing countries

While studies using data for developing countries tend to support the quantity−quality trade-off theory, the evidence for developed countries is less supportive. Linking data from the 1983 and 1995 Israeli population censuses with population registry data, a study finds that the number of children in a household does not affect child education [3]. This conclusion holds even when the study focuses on people of Asian and African origin whose fertility rates are comparable to rates in developing countries. The estimated impact of child quantity on child quality is not sensitive to whether the variation in child quantity is due to twin births or to the sex composition of earlier-born children (parents are more likely to have a third—or more—child if their earlier-born children are all of the same gender). Another study applies similar identification strategies to a Norwegian sample of people aged 16–74 between 1986 and 2000, and at least 25 years old in 2000. The study finds that the variation in the number of children caused by twin births does not affect the educational attainment of the first-born child [4]. These findings are consistent with those of the Israeli study [3] but are inconsistent with the results of studies for developing countries.

First-born and later-born children

While the number of children in a family does not affect the quality of first-born Norwegian children, it has a significant negative impact on the educational attainment of second- and third-born children, an impact that is attributed to birth-order effects [4]. The confluence theory posits that a family's intellectual environment (which is positively correlated with the average mental age of parents and children within the family) deteriorates as more children are born into the family because of the lower mental development of younger children. Since older (earlier-born) children grow up in a more favorable intellectual environment than their younger siblings, they tend to be better educated. Moreover, older children also have an opportunity to teach their younger siblings, which stimulates the growth of their intellectual capabilities.

Since low birth-order children are likely to have fewer siblings than high birth-order children (which implies that the child is from a large family), the observed negative correlation between children's education and their birth order could also be driven by the number of children. If this is the case, the estimated birth-order effect should disappear once the impact of child quantity is accounted for. The large sample constructed for the Norwegian study makes it possible to accurately separate the impact of birth order from that of the number of children [4]. The study finds that higher birth-order children always have fewer years of schooling, and the size of the difference across birth orders does not depend on the number of children in the family. The study concludes that “there is little if any family size effect on child education,” which implies that first-born children will benefit little from a decline in fertility [4], p. 697. However, since a decline in fertility reduces the number of higher birth-order children, the average education level would still be negatively correlated with fertility at a national level.

Using twin births or the gender composition of the early-born children to identify the effect on low-parity children suffers from the sample truncation problem: high-parity children have been excluded from the sample [11]. An insignificant or negligible estimate of family size effect on low-parity children does not predict a negative effect of family size on average child quality. This could explain the inconsistent findings of quantity–quality trade-off in some studies.

Planned and unplanned children

The impact of quantity on quality could depend on whether the increase in the number of children is unplanned or planned. If the increase is driven by the gender composition of earlier-born children (hence planned), parents could reduce family expenditures before giving birth to the additional child. In this case, having another child might not significantly affect per child expenditure. A recent Norwegian study supports the argument [12]. Using a comprehensive matched administrative data set of Norwegian men born between 1967 and 1998, the study finds that variations in child quantity resulting from the birth of twins have a significant negative effect on the IQ scores of first-born children, while variations in the number of children motivated by parents’ concern about the gender composition of earlier-born children have no significant impact on children's IQ. The authors find similar results even if they use educational attainment rather than IQ as the outcome variable.

The differences between the two Norwegian studies suggest that the impacts of child quantity are stronger for the recent cohorts of Norwegian men (born between 1967 and 1998) than for the earlier cohorts (born between 1902 and 1975) [12]. Given that the findings of the earlier Norwegian study [4] are consistent with those of the Israeli study [3] that used similar identification strategies on individuals of similar birth cohorts (an average person in the Israeli study was born in the mid-1960s), it is not clear whether the evidence for recent birth cohorts in the later Norwegian study [12] can be generalized to other countries. Moreover, whether parents can adjust financially in anticipation of having an additional child and thus lessen or avoid any potential negative impact on child quality depends on whether parents have adequate resources to do so.

Other measures of child quality

Besides examining the impact of child quantity on educational attainment, studies have also examined its impact on other measures of child quality such as anthropometric indicators (measures of the human body) and on inputs to child quality, such as educational expenditure, private school enrollment, mother's labor force participation, and child labor. The advantage of examining inputs is that these variables are directly linked to parental decisions. As one study asserts, “focusing on inputs is a more powerful test than using outcomes since inputs are one step closer to assessing the effects of family size in the causal chain” [13], p. 739.

Some studies examine the impact of child quantity on anthropometric indicators, such as height-for-age [6]. The anthropometric indicators reflect children's long-term nutritional status. Because these indicators are closely related to children's mental development, mortality, and adult wages, these indicators should be strongly and positively correlated with other quality measures, making them valid quality measures in their own right. Since adult stature is largely determined during gestation and early childhood, these indicators should be more sensitive to parental decisions than the measure of education, which depends on parental investment and children's efforts.

Drawing on data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey and taking advantage of the variation in the number of children resulting from the relaxation of China's one-child policy, a study finds that an additional child has a significant negative impact on height-for-age at the mean for both boys and girls [6]. The impact is not uniform. For boys, the impact of an additional child on height-for-age is stronger among families that tend to have shorter children. The impact declines gradually with child height and is no longer significant among families that tend to have taller children. For girls, the impact is strongest for children in median-size families and weaker for children in families that tend to have either shorter or taller children. To test whether the results are sensitive to the choice of child quality measures, the study also examines the impact of family size on educational attainment. The impact is never significant for boys, and it is significant for girls only at the mean.

Once again exploiting the exogenous variation in child quantity induced by twin births, another study using data for the US finds that having an additional child reduces the oldest child's probability of attending private school by 1.2 percentage points [13]. Having more children also reduces the mother's labor force participation and increases the parents’ probability of divorce. These findings suggest that even in wealthy countries such as the US, having an additional child could significantly reduce children's education expenditure. However, the study fails to find any significant negative effect on children's education as measured by grade retention (repeating a grade in school). Thus, while having more children reduces parental investment in each child, the reduction might not be large enough to generate discernable differences in child quality.

Yet another study, this one for Brazil, examines the variations in child quantity introduced by twin births and finds that an additional child raises the labor force participation rate (working or actively looking for a job) of children aged 10–15 by 2 percentage points for boys and 1.4 percentage points for girls [1]. Under the assumption that children who work would have less time to study and thus accumulate less human capital, this evidence also supports the quantity–quality trade-off theory.

Thus the evidence indeed suggests that the choice of quality measure could play an important role in testing the quantity−quality trade-off theory.

Limitations and gaps

Except for the two Norwegian studies [4], [12], and the Israeli study [3], which uses administrative data, all the other studies use survey data. One limitation of using survey data is that researchers have information on children only if they live with their parents in the survey year. As older children tend to live on their own, these studies have to focus on relatively young children. Whether the impacts last to adulthood is still an open question, and further studies on this issue are needed.

Summary and policy advice

What do these seemingly conflicting results tell about the hypothesized child quantity–quality trade-off? First, because of differences in institutional settings, the quantity−quality trade-off—if it indeed exists—is likely to take different forms in different countries. For instance, in countries like Norway, where all education, from pre-school through college, is free of charge, it is not surprising that the number of children does not affect educational attainment. However, in countries where attending even primary school is a financial burden for many families, like India in the 1960s, family size can significantly negatively affect children's education. In general, the trade-off is likely to be more pronounced in developing countries than in developed countries. Second, when quality is assessed by “inputs” into child quality, such as education expenditure per child or private school enrollment, or by measures that are heavily influenced by parental choices, such as child labor, the impact is likely to be significant.

Several policy implications can be drawn from these studies. First, government policies, such as increasing the availability of contraceptives, which encourage couples to have fewer children, could stimulate parental investment in child health and education. Second, while a decline in fertility could boost expenditures per child on education and health care, these increases might not be big enough to generate discernable differences in child quality in developed countries. Third, in countries with very low fertility—which are much more likely to be developed countries—policies that seek to increase fertility, such as the discounted public transportation and large tax reductions for families with three or more children adopted by France, are unlikely to have any significant negative impact on child quality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank one anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the figures, adds a new section on the stringency of family control policies, and includes new “Key references” [2], [7], [8], [10], [11].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Li Li and Haoming Liu