Elevator pitch

How does tax evasion affect the distribution of income? In the standard analysis of tax evasion, all the benefits are assumed to accrue to tax evaders. However, tax evasion has other impacts that determine its true effects. As factors of production move from tax-compliant to tax-evading (informal) sectors, these market adjustments generate changes in relative prices of products and factors, thereby affecting what consumers pay and what workers earn. As a result, at least some of the gains from evasion are shifted to consumers of goods produced by tax evaders, and at least some of the returns to tax evaders are competed away via lower wages.

Key findings

Pros

Tax evasion creates a cascade of market adjustments as firms and individuals react to changing incentive structures.

Successful tax evasion may encourage others to enter the same occupation as the evader, and new entry will reduce the advantage of tax evasion.

A full analysis of the effects of tax evasion must recognize and incorporate general equilibrium adjustments via the interactions of supply and demand across multiple markets.

Recent research that incorporates general equilibrium adjustments suggests that tax evasion has large, and often neglected, effects on the distribution of income.

Cons

Standard tax incidence analysis does not adequately consider how tax evasion affects the distribution of income.

Most research neglects general equilibrium adjustments, resulting in incomplete and potentially misleading findings.

No study has yet simultaneously examined the full range of relevant factors.

As a result, knowledge of the true effects of tax evasion remains incomplete.

Author's main message

Standard analysis of tax evasion assumes that the main beneficiaries are the evaders themselves. However, tax evasion causes broader market adjustments that affect the distribution of income. Any tax advantage from evasion diminishes as labor and capital move into the tax-evading sector and as competition and substitution possibilities in production increase. Moreover, when tax evasion reduces some of the distorting effects of taxation, it may even increase the welfare of all households. Policymakers must recognize such market adjustments in order to understand the true impact of taxes on income distribution.

Motivation

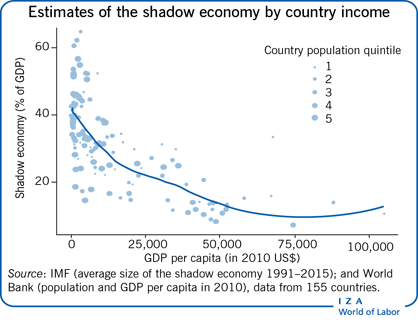

A central concern of policymakers is the effect of taxation on income distribution. However, when individuals and firms cheat on their tax obligations through tax evasion, these actions alter the true effects of taxation, especially the effects on income distribution. Most standard analyses ignore these distributional consequences and assume that the main—and only—beneficiaries of tax evasion are the evaders themselves. However, recent empirical work has begun to inspire new research on the effects of tax evasion on inequality [1]. One result from this new work is that tax evasion may aggravate inequality, because opportunities to evade taxes tend to increase with income. For example, a recent study finds that individuals at the top end of the income distribution use tax havens to hide substantial shares of their wealth, thus increasing wealth disparities [2]. Even so, firm evidence on the distributional effects of tax evasion remains unresolved.

Tax evasion is central to public economics. Its most obvious impact is reduced tax collections, thereby affecting the taxes that compliant taxpayers face and the public services that citizens receive. Beyond the revenue losses, evasion leads to resource misallocation when people alter their behavior to cheat on their taxes, such as their choice of hours to work, occupations to enter, and investments to undertake. Moreover, governments have to expend resources to detect, measure, and penalize noncompliance. Noncompliance alters the distribution of income in arbitrary, unpredictable, and unfair ways, and it affects the accuracy of macroeconomic statistics.

The standard analysis of tax evasion (based on [3]) assumes that the offender keeps the evaded tax in its entirety and so is the sole beneficiary of tax evasion. However, this assumption is incomplete and misleading. The act of tax evasion sets in motion a range of general equilibrium adjustments, as individuals and firms react to the changes in incentives created by evasion. These adjustments lead to changes in factor wages and product prices, which generate movements in factors and products. All these adjustments affect the final prices that determine the true income distribution effects of tax evasion. As argued in a study from the 1990s [4] and a much more recent one [5], a full analysis of the effects of tax evasion, and so of the incidence of taxation, must recognize and incorporate these general equilibrium adjustments. The failure of the standard approach to consider these effects leads to a wide variety of errors.

Once these general equilibrium adjustments are recognized, it is no longer obvious that the main beneficiaries of tax evasion are necessarily the individuals who engage in the evasion; indeed, they may not benefit at all.

Discussion of pros and cons

To anticipate the basic argument, consider the standard example of the individual (e.g. working as a home care provider or day laborer) who successfully evades the individual income tax. Now, suppose that successful evasion attracts other individuals into the same sector as the evader, driving down both wages and product or service prices. In this case, the ultimate beneficiaries are not the evaders, but rather the consumers of the product or service produced in the evaders’ sector. The true beneficiaries of successful evasion are thus likely to be the consumers of these services, once market adjustments are recognized. The standard analysis of tax evasion ignores these adjustments and so gives a misleading or incomplete picture of the distributional effects of tax evasion [4].

The standard approach to tax evasion and some extensions

The originators of the standard approach to tax evasion applied the economics of crime model directly to tax evasion (see [5] for a recent assessment). The basic model is essentially a portfolio approach in which a rational individual compares the expected utility of being detected and paying a penalty for tax evasion to the expected utility of being able to keep the evaded tax income. In this simple formulation, the successful evader is the exclusive beneficiary and keeps the entire gains.

However, the portfolio model and its many extensions assume that underlying “prices” (especially income in the simplest form of the model) are fixed and exogenous, and it ignores the broader economic context in which an individual makes the tax evasion decision, including how to spend the evaded tax income. This approach ignores market forces that work to eliminate the tax advantage created by evasion opportunities, as factors and products flow into and out of affected activities and thereby change both factor and product prices. These forces can be analyzed only in a general equilibrium framework.

Several studies have used a general equilibrium approach to examine tax evasion, but, as will be discussed below, no single study has included all of the elements that are essential for a full analysis of the distributional effects of tax evasion. One study uses a multi-consumer, multi-sector general equilibrium model to make qualitative and quantitative assessments of the effects of tax rate changes on evasion activity, relative output prices, and real tax revenues [6]. The study finds that higher tax rates drive resources out of the compliant sector into the evading sector if government consumes products from both sectors in the same proportion as households and if higher tax rates do not affect evasion costs. However, if higher tax rates raise tax evasion costs for individuals who would otherwise comply and if government purchases are biased toward the compliant sector, then higher tax rates could lower tax evasion. Despite the many insights from this work, it is incomplete because it does not allow for uncertainty in individual evasion decisions.

Some other studies allow for uncertainty but have other missing elements. One study analyzes a model with two labor markets that offer differing evasion possibilities and looks at the effects of changes in tax, penalty, and audit rates on the allocation of labor across markets [7]. However, although the study allows for labor markets, it does not consider capital markets and so cannot examine the full range of general equilibrium effects that evasion may create, especially the effects of factor mobility on capital prices and the distribution of capital income.

Another study develops an expected utility model with two types of actors: evaders and compliers [8]. Individuals do not know the true audit rates but learn them over time by looking at the behavior of others. These information cascades are shown to explain the connections between a potential evader, the number of evaders caught in previous periods, and the total number of evaders. However, despite allowing for mobility between evaders and compliers, the study assumes that prices are not affected by this movement.

A more recent study uses a dynamic general equilibrium model to investigate how tax evasion by self-employed taxpayers affects aggregate outcomes and inequality [9]. Self-employed agents can evade a share of their income, but they face the risk of being detected by the tax authority, while workers in these sectors cannot evade taxes and make only consumption and saving decisions. The numerical analysis for US data suggests that tax evasion by self-employed taxpayers affects aggregate outcomes and, through these general equilibrium impacts, also affects inequality. As a result, evasion increases the size of the self-employment sector, but decreases the average size and the productivity of self-employed businesses. Moreover, the economy with tax evasion produces higher aggregate savings and more output than the economy with perfect enforcement. Because higher saving rates lead to lower interest rates and increases in labor productivity lead to higher wages, wealth inequality is actually reduced by evasion. However, while this model incorporates general equilibrium effects and uncertainty in the decision to evade taxes, the model assumes that labor supply is inelastic, it includes only workers and self-employed owners of small businesses, and it allows only for a single consumption good.

Pitfalls in the distributional analysis of tax evasion

The failure to consider all general equilibrium adjustments invariably leads to incorrect conclusions about the incidence of tax evasion [4].

Empirical studies of tax compliance typically take the economic environment as fixed and unaffected by individual compliance decisions. Frequently, findings are adjusted to take into account the impact of existing evasion, such as professionals who do not report income or unskilled workers who are employed in the informal (untaxed) sector of the economy. However, these adjustments are made under the assumption that the evading groups benefit exclusively and fully from the assumed tax evasion. This implicit assumption leads to a variety of errors.

As one example, a study using this type of analysis for Jamaica estimates the tax evasion that occurs through income underreporting and nonreporting and uses these estimates to calculate the true burden of taxation [10]. However, because the study assumes that tax evaders retain all benefits from their evasion, the resulting estimates of the true burden of taxation are misleading. As a second example, another study of income tax reform in Jamaica assumes that, if labor income is more likely than capital income to be generated in the untaxed or informal sector, then the existence of tax evasion makes the tax system more progressive [11]. However, this conclusion will be wrong if the advantages realized by workers get capitalized or competed away by market processes. With easy labor entry into, say, the Jamaican tourism industry, it may not be undocumented workers in the sector who benefit from successful tax evasion but rather the consumers of tourism services, who benefit from lower prices for the services produced by workers who do not pay taxes.

These types of errors are also found in important work that analyzes the historical development of inequality, which generally finds that tax evasion exacerbates inequality. For example, a recent study combines data from random tax audits, leaked information from offshore financial institutions, and national wealth records from Scandinavian countries to estimate the magnitude and distribution of tax evasion [2]. The authors assume that evasion increases wealth disparity because opportunities to evade taxes increase with income. The study finds that taxpayers at the upper end of the wealth distribution (or the top 0.01%) hold 50% of the assets in offshore tax havens and evade almost 30% of personal taxes, compared to an average across all taxpayers of approximately 3%. A subsequent study estimates how tax evasion affects the wealth share of the top 0.01% of the wealth distribution across a sample of developed and developing countries [12]. The authors find that accounting for offshore assets increases the wealth share of the wealthiest substantially, with effects that vary considerably across countries. However, while important, these studies are incomplete because they do not consider general equilibrium effects of tax evasion.

Some essential elements of a complete model on the effects of tax evasion

While some of these studies have added considerably to an understanding of the general equilibrium adjustments that occur with tax evasion, they do not fully address the main distributional effects.

The features that a model must have to capture these distributional effects are [4]: first and foremost, the model should capture the potential general equilibrium effects of tax evasion that induce changes in the relative prices of factors of production and products. Any tax advantage from evasion will be reflected in expected factor income or firms’ expected profits. The potential mobility of resources, especially labor, will then lead to the necessary price adjustments until the advantage is eliminated. The general equilibrium model should also allow for differences in endowments and preferences, so that different groups may benefit differently from changes in relative prices.

Second, the model should incorporate uncertainty in an individual's or a firm's decision to evade taxes in at least one sector of the economy. This uncertainty simply reflects tax evasion as an opportunity facing the individual or firm that has a random payoff; that is, evasion may be successful or it may be detected by authorities, each with associated probabilities and consequences.

Third, the model should allow for varying degrees of competition or entry across sectors, including the sectors in which tax evasion is prevalent. This includes factor mobility, such as labor in the case of income tax evasion; it also includes free firm entry, as in the case of sales tax or corporate income tax evasion. Mobility is critical for showing how much of the tax advantage is retained by the initial tax evaders and how much is shifted elsewhere through factor and product price changes.

A complete analysis of the incidence of tax evasion therefore requires the consideration of general equilibrium effects in a setting in which agents can differ in preferences and endowments, uncertainty is present, and mobility can vary across sectors. At one extreme there might be a case of no shifting at all because, for example, there is no factor mobility or no free entry. In this case, successful evaders keep all unpaid taxes, and there are no changes in relative prices of factors of production or products as a result of the evasion activity. Examples include occupations with strict entry requirements or strong regulations that make mobility difficult. At the other extreme there might be a case in which the tax advantage gets fully shifted because entry is unrestricted and the supply response is large enough to compete away any residual tax advantage. This could happen if there was a very elastic supply of potential taxpayers who had no choice but to work in the untaxed or informal sector. Examples are the presence of a pool of unskilled laborers in a developing economy with limited opportunities for employment or of undocumented workers in a developed economy who also have limited opportunities. It is unlikely that these workers would be able to keep any tax evasion benefit from working in an informal sector. Instead, the likely beneficiaries are buyers of the products and services produced in the informal sector.

These guidelines are used in the following sections to illustrate weaknesses in several recent approaches that analyze the impacts of tax evasion in a general equilibrium framework.

Three examples of computable general equilibrium modeling

This section presents three numerical simulation models that use many of the essential elements for analyzing the general equilibrium effects of tax evasion. These models maintain the basic features of the simplest general equilibrium model of tax incidence: “factor substitution effects” (e.g. the taxed factor bears more of the burden), “factor intensity effects” (e.g. the factor used intensively in the taxed sector bears more of the burden), and “demand effects” (e.g. consumers who purchase more of the taxed product bear more of the burden). These basic features determine the final pattern of the benefits of tax evasion.

A general equilibrium model, but with only a single agent and no uncertainty

As a first example, an older study examines the impact of taxes that create an incentive for resources to flow from a taxed and tax-compliant official sector X to two untaxed underground sectors: sector Y, whose activities are untaxed substitutes for those of the taxed sector; and sector Z in which traditionally illegal activities take place, such as prostitution, gambling, and drug dealing [13]. Demand for the output of each sector is assumed to be determined by relative prices, and for simplicity all agents (including government) are assumed to have the same (average and marginal) propensity to consume each product. Each product is produced under competitive conditions in which the amounts of capital and labor are assumed to be fixed in supply and perfectly mobile between sectors. Perfect mobility means that net factor returns must be equalized across sectors, adjusting for any risk premia in the untaxed sectors.

Since capital and labor in the underground sectors Y and Z are assumed to be untaxed, there are only two taxes: a tax on capital and a tax on labor in the taxed sector X. Taxation of capital and labor in only some of their uses creates an incentive for resources to flow from the taxed sector (X) to the untaxed sectors (Y and Z). Although this movement has both allocative and distributional effects, the distributional effects are the focus here.

The crucial element of the model affecting the distributional effects is the assumption that the two untaxed sectors are labor intensive. As a result, the taxation of labor and capital in the taxed sector X generates adjustments that impose a greater burden on the factor used intensively in that sector (the “factor intensity effect”), which is capital. The model calibration, using US data, demonstrates that the tax rate is typically higher on capital than on labor, so that the higher tax on capital relative to labor in sector X reduces the relative price of capital (the “factor substitution effect”). Finally, the movements of factors and products increase the price of the product of the taxed sector X relative to the prices of the products of the two untaxed sectors Y and Z, thereby imposing a higher burden on consumers of the product of sector X (the “demand effect”).

The ultimate impact on the equity of the tax system then depends on how to evaluate the shift in the burden of taxation of labor and capital in the taxed sector X to capital and to consumers in the untaxed sectors Y and Z. For example, a typical simulation estimates that mobility lowers the price of capital relative to labor in 1980 by 41–55% over its initial price (depending on elasticities), raises the price of the product in sector X by roughly 50%, and lowers the price of the product in sector Y by about 2%, with both product price changes measured relative to the price of the product in sector Z. These results are largely robust to different model assumptions.

However, the model assumes a single representative agent, so it cannot fully examine the different distributional effects of the general equilibrium adjustments. It also does not allow for uncertainty in the agent's decisions, preventing examination of the agent's underlying tax evasion choices. Finally, there is the clearly unrealistic assumption that private agents and government have the same average and marginal propensities to consume all products (legal and illegal).

Another general equilibrium model, but with constrained mobility and no provision for firm-level tax evasion

Some of the above limitations are addressed in another general equilibrium model that describes a stylized small, static, closed economy with two consumers (poor and rich), two factors (labor and capital), and an official tax-compliant sector X and an informal, tax-evading sector Y whose product is a substitute for the taxed output [14]. The model incorporates the individual's decision to evade and also allows for varying degrees of mobility through competition and entry across sectors. The focus is on measuring how much of the initial tax advantage from evasion is retained by income tax evaders and how much is shifted through factor and product price changes made possible by mobility. The model is calibrated with data reflecting the sectoral composition in a typical developing country.

Across all experiments, the tax evader is not the exclusive beneficiary of the tax evasion, and not even the largest beneficiary. The household that evades its income tax liabilities has a post-evasion welfare gain that is only 1.1–3.4% higher than its post-tax welfare would have been had it fully complied with the income tax. This household keeps only 75.3–78.2% of its initial increase in welfare, while the rest is competed away as a result of mobility that reflects competition and entry into the informal sector. The household that complies with the income tax experiences an initial negative welfare effect, but, as a result of the reduction in the prices through competition and entry in the informal sector, its welfare increases by 87.5–142.3%. Thus, the tax-evading household benefits only marginally, and the advantage diminishes with mobility through competition and entry in the informal sector. There are even some circumstances under which tax evasion increases the welfare of all households, because evasion reduces some of the distorting effects of taxation.

In short, at least some of the gains from tax evasion are shifted from the evaders to the consumers of their output through lower prices. As more workers enter the tax-evading sector, their production pushes down the relative price of their output and consequently lowers their hourly returns; the movement of workers and capital between sectors also changes the relative productivity of workers in each sector. In equilibrium, the gains from evading taxes for the marginal entrant to the informal sector are offset by the relative price and productivity effects.

Despite some improvements over the simpler model described above [13], this model still does not incorporate all essential elements: it does not fully allow for mobility, especially mobility that can be affected by the degree of competition in the production sectors, and it does not consider the potential for firm-level tax evasion.

A third general equilibrium model, with firm-level tax evasion but without individual evasion and differential effects on individuals

This third model describes another stylized small, static, closed economy with an official taxed sector and an underground, tax-evading sector whose output is a substitute for the taxed sector output [15]. It also incorporates uncertainty and varying degrees of mobility across sectors. It differs from previous models ([13], [14]) by modeling tax evasion for a sales tax as well as for a labor tax and by more explicitly incorporating different degrees of competition (perfect competition and a monopoly mark-up model). The focus is on measuring how much of the initial advantage from tax evasion is retained by the tax evaders and how much is shifted through factor and product price changes stemming from mobility.

Across various experiments, the benefits of income tax evasion remain with the tax-evading sector and benefit the factor used more intensely there (labor) when there is little labor mobility. However, when factor inputs become perfect substitutes, the benefits of evasion are competed away through replication and competition. Overall, the benefits of evasion are replicated and competed away through entry or through the reallocation of factor inputs, depending on the relative competitiveness of the market. Industries in which one factor input is used more intensively than the other or in which there is market power are able to retain the benefits of evasion.

While this approach is also an advance over the simpler models ([13], [14]), it does not consider individual evasion or allow for differential impacts across individuals.

Limitations and gaps

The three studies outlined in more detail above represent an advance over much of the previous work. However, each study still has some limitations, and none incorporates all of the essential elements required for a complete analysis of taxation's distributional effects that policymakers need to inform their decisions. Specifically, no single study incorporates these three crucial elements: account for all potential general equilibrium adjustments, require agents to behave under uncertainty, and allow for different degrees of competition and entry across individuals and firms.

There are many possible extensions to this work, even aside from the usual sensitivity analyses. The underlying framework could be generalized to consider greater differences among taxpayers, a broader range of government activities, the impacts of an open economy, the potential for government corruption, and dynamic incidence factors. An important extension is to more fully incorporate expected and unexpected utility models of individual behavior. It would be informative to examine whether traditional tax equivalences still hold in the presence of tax evasion, such as the presumed equivalence between a proportional income tax and a proportional consumption tax (with an equal rate on all products). Perhaps most important is the need to incorporate some other essential elements of the fiscal architecture, notably the administrative and compliance costs of taxation. All of these extensions are needed to provide policymakers with a complete analysis of how taxes affect the true distribution of income.

Summary and policy advice

Fully understanding how taxes affect the distribution of income requires accounting for how tax evasion affects factor and product prices. The standard analysis of tax evasion, which looks only at a single market and ignores the ways in which changes in one market may affect related markets, leads to a wide variety of errors. Conclusions drawn from the standard approach are unsatisfactory because they ignore the fact that tax evasion is much like a legal tax advantage and therefore that replication and competition work to eliminate the advantage. The adjustment takes place through changes in the relative prices of products and factors of production, as factors move into and out of sectors.

Once the market interactions are appropriately modeled, it is typically found that the tax evader is not the exclusive beneficiary of evasion. Analyses indicate that any tax advantage from evasion diminishes with factor mobility into the informal sector, with greater substitution possibilities in production, and with more sectoral competition. There are even some circumstances under which tax evasion increases the welfare of all households, as evasion reduces some of the distorting effects of taxation.

The gains from tax evasion shift at least in part from the evaders to the consumers of their output, through lower prices, as changes in relative prices and productivity eliminate the incentive for workers to enter the informal sector beyond some marginal point. As more workers enter the informal sector, their production pushes down the relative price of the sector's output and consequently the hourly returns of working in the sector. The movement of workers and capital between sectors also changes the relative productivity of workers in each sector. In equilibrium, the gains from evading taxes are offset by these relative price and productivity effects for the marginal entrant to the informal sector.

How are these considerations relevant for the current debate on the effects of taxation on inequality? Individuals at the top end of the income distribution have both stronger incentives to evade and more possibilities to do so. Some current estimates suggest that these households use tax havens to evade up to 25% of the taxes they owe [2], and this mechanism is considered to be a major driver of growing inequality. However, much of this “hidden wealth” is not merely parked in tax havens, but rather invested in other economic ventures. At least part of the gains that accrue from these ventures affect agents other than the evader. Tax evasion by individuals at the top end of the income distribution might well have implications that go beyond, and potentially reduce, the negative effects of their tax evasion on equality.

As described above, additional extensions to the new general equilibrium models are needed to provide policymakers with a complete analysis of how taxes affect the true distribution of income. More broadly, it is not possible for policymakers to understand the true impact of taxation without recognizing its general equilibrium effects, including the general equilibrium effects of tax evasion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank several anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier versions. They are especially grateful to Keith Finlay, Edward Sennoga, and Sean Turner for their many contributions to the understanding of the distributional effects of tax evasion. The authors are also grateful to Roy Bahl, Richard Bird, Kim Bloomquist, Brian Erard, Erich Kirchler, Jorge Martinez-Vazquez, Michael McKee, Matthew Murray, Friedrich Schneider, Joel Slemrod, and Benno Torgler for many helpful discussions over the years. Version 2 of the article explores the effects of tax evasion on inequality, adds a new “Graphical abstract,” and includes new “Key references” [1], [2], [5], [9], [12], [15].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© James Alm and Matthias Kasper