Elevator pitch

All developed economies have unemployment benefit programs to protect workers against major income losses during spells of unemployment. By enabling unemployed workers to meet basic consumption needs, the programs protect workers from having to sell their assets or accept jobs below their qualifications. The programs also help stabilize the economy during recessions. If benefits are too generous, however, the programs can lengthen unemployment and raise the unemployment rate. The policy challenge is to protect workers while minimizing undesirable side effects.

Key findings

Pros

By replacing some lost income, unemployment benefits protect unemployed workers from depleting their assets to maintain consumption.

By augmenting the income of very low-income households, unemployment benefits help keep them out of poverty.

Unemployment benefit programs encourage workers to accept jobs that are important to the economy, despite layoff risks.

Unemployment benefits enable workers to maintain consumption while spending more time searching for a job fitting their skills.

Unemployment benefits provide additional support to workers during recessions, without large negative side effects.

Cons

Unemployment benefit programs can lengthen unemployment spells excessively, especially when maximum benefits continue over long periods.

Unemployment benefit programs modestly raise the national unemployment rate—and by less during recessions.

There is no strong evidence that unemployment benefit programs help people find better paying jobs or jobs better matched to their skills.

Without official monitoring, unemployed workers might exaggerate their job search activity and so may stay unemployed longer.

Unemployment benefit systems financed by payroll taxes may vastly increase layoffs in some industries.

Author's main message

Unemployment benefit programs play an essential role in the economy by protecting workers’ incomes after layoffs, improving their long-run labor market productivity, and stimulating the economy during recessions. Governments need to guard against benefits that are too generous, which can discourage job searching. Governments also need a system for monitoring job search intensity, to reduce negative side effects on the unemployment rate and job creation.

Motivation

All developed economies have unemployment benefit programs that provide income to laid-off workers to enable them to meet their basic consumption needs. However, when unemployment benefit programs are particularly generous, in both benefit level and duration, they are controversial because of potential negative side effects. The debate over generosity intensifies during recessions and economic downturns, such as those in Europe and North America today, when overly generous programs may slow the decline in the unemployment rate and delay a country’s economic recovery.

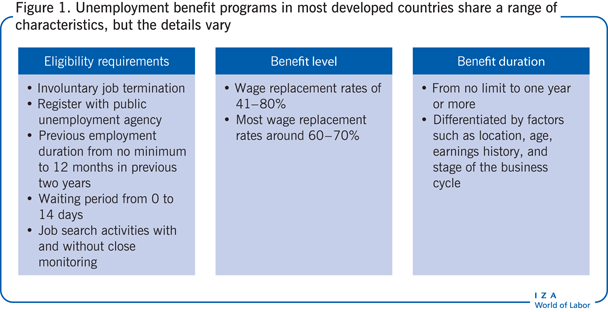

Several dimensions of unemployment benefit programs influence their positive and negative impacts on individuals and the economy. In some areas the evidence on impacts is clear; in others it remains ambiguous. Governments can take several steps to increase the positive impacts and reduce the negative ones (Figure 1).

Discussion of pros and cons

Unemployment benefit programs in developed economies are similar in structure, but many of the details—eligibility requirements, benefit levels, and benefit duration—vary. These details can have different effects on consumption, poverty levels, employment, job-seeking, and duration of unemployment. The effects can also vary with the phase of the business cycle.

Structure of unemployment benefit programs in advanced economies

Unemployment benefit programs in advanced industrialized economies share many features, but the details vary in ways that matter for government policy and for the effects of the programs on individuals and the economy. Three of the most important dimensions of a country’s unemployment benefits program are eligibility requirements, benefit level, and maximum duration of benefits.

Eligibility requirements

Virtually all developed countries tie eligibility for unemployment benefits to being involuntarily terminated from a job—people who quit their jobs are not eligible. All countries also require that anyone who meets this criterion must register at a government unemployment office, list their job experience and qualifications, and receive information on job openings for workers with their qualifications. Finally, all countries require that unemployed workers seeking benefits actively search for a job, although how this requirement is enforced varies considerably.

How long a person has to have worked before being eligible for unemployment benefits after being involuntarily discharged varies as well. Most countries require applicants to have spent some minimum percentage of the previous year or previous two or three years in employment (for example, 6 months out of the past year or 12 months out of the past two years). But some countries, notably Australia and New Zealand, have no length requirement for previous employment. Some countries, such as Norway and the US, also require that applicants have received some minimum level of earnings over those employment periods to qualify for unemployment benefits.

Some countries also require a waiting period before benefits begin. While about half of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries allow eligible applicants to start to receive benefits immediately after losing a job, the other half have waiting periods of 3–14 days.

Benefit levels

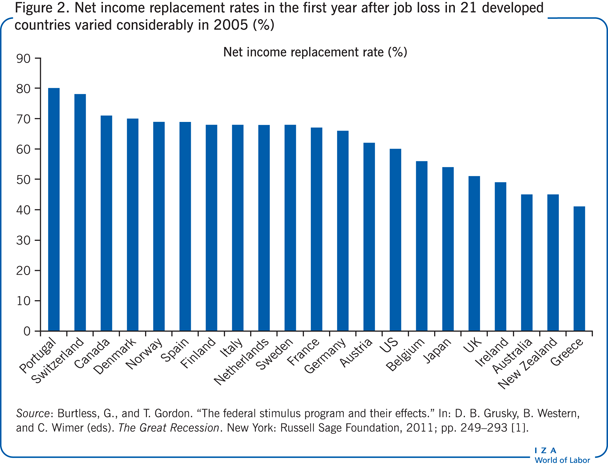

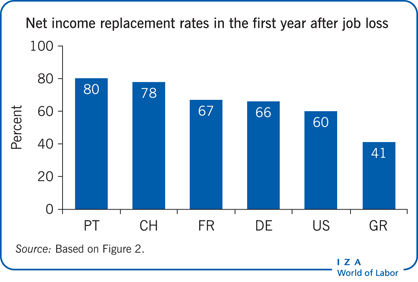

Most countries base benefit levels on past earnings or on a national earnings index, but the levels vary dramatically across countries. The most common measure of benefit level is the replacement rate, which is the ratio of benefits received to the individual’s earnings on the terminated job for which unemployment benefits are being claimed. The replacement rate in 21 developed economies in 2005 varied from 41% in Greece to 80% in Portugal, or twice as high (Figure 2). In a majority of countries replacement rates were 60% or higher.

Benefit duration

The maximum duration of benefits also varies widely. Some countries have no limit (such as Australia, Belgium, and New Zealand), and some have a limit of one year or more (such as Denmark, Finland, France, and the Netherlands). But more countries have limits of a half year or less (such as the UK and the US). Many countries differentiate the duration of benefits for workers of different types, such as by residential location, earnings history, and age. For example, in Germany limits vary by age, ranging from 6 to 24 months, with older workers eligible for longer periods.

Canada, Poland, and the US are unique in changing the maximum duration of benefits over the business cycle. Canada sets a higher maximum length when the regional unemployment rate is higher, while Poland increases the maximum length when the local unemployment rate exceeds the national average. The US has both a trigger system that raises the maximum length in a state when the state unemployment rate reaches a certain level, and national legislative authority to raise the maximum length in all states when the national unemployment rate is high.

Effects on consumption

The aim of all unemployment benefit schemes is to make up some fraction of the lost income for unemployed workers and thereby allow them to maintain their consumption at a reasonable level despite the loss of wages.

Although it might seem obvious that unemployment benefits would raise consumption, the amount by which it does so depends on several factors. One is the amount of savings a person has accumulated before becoming unemployed. Most households in developed economies have at least some savings and have built up assets for a “rainy day.” However, the amount of savings is typically small, and very low-income families often have no savings at all. But for people who have accumulated savings, consumption levels may remain fairly high even in the absence of unemployment benefits.

Some people who are unemployed use a portion of their unemployment benefits to reduce their debt rather than spending it all. And some people who are unemployed have access to other sources of income. In many countries means-tested transfer programs provide income support to low-income households, for example. To the extent that these income support programs already allow unemployed workers to maintain their previous consumption levels, the extra effect of unemployment benefits could be small. And in many households when a member loses a job, other working members can help maintain household consumption levels even without unemployment benefit payments.

However, even with all these ways of maintaining some consumption after losing a job, the evidence indicates that unemployment benefit programs increase consumption considerably [2], [3]. There is evidence, for example, that a 10% increase in the unemployment benefit replacement rate reduces the drop in consumption among unemployed workers by 2.65% and that people who do not receive unemployment benefits have to reduce their consumption by more than 22%. Replacement rates at or above 84%—the case in a small fraction of countries—allow households to maintain consumption levels at their pre-unemployment levels while using savings to supplement the unemployment benefit payments. Replacement rates around 60%, much more common, enable people to maintain most of their previous consumption. A study found that the positive effects on consumption are much larger among recipients of unemployment benefits who have no assets and no employed spouse [2]. This is consistent with the assumption that whether people are able to maintain consumption even without unemployment benefit payments depends on whether the household has accumulated savings and whether there are other sources of household income.

These positive effects on consumption are particularly helpful to the economy during economic downturns. During times of high unemployment, workers’ incomes fall and so does their spending. That reduction in spending reduces aggregate demand for goods, leading businesses to reduce production, output, and employment, which further depresses spending and then production again. Unemployment benefit programs work against this downward spiral by stabilizing the incomes of the unemployed and reducing any drops in spending. The net effect, therefore, is to reduce the fall in gross domestic product and to mitigate the effects of a downturn. Unemployment benefit programs are called “automatic stabilizers” in an economy: when the economy is doing well, they do not pay many benefits and so do not increase spending, but when the economy is doing poorly, they automatically increase spending, which is precisely what the economy needs at that point in the business cycle.

Effects on poverty

An additional question for unemployment benefit schemes is whether they lower a country’s poverty rate. Research suggests that they reduce the aggregate poverty rate (calculated over all households in the economy, employed and unemployed) by almost one percentage point. The impact is much greater for people receiving unemployment benefits; poverty rates for this group drop from 22.5% to 13.6% as a result of the program.

Effects on employment

The existence of an unemployment benefit program lowers the risk of taking a job that could later result in a layoff by insuring at least partially against that risk. This is called the entitlement effect of unemployment benefit programs (see The economic functions of insurance). Because nearly all countries have qualifying periods of work for unemployment benefit eligibility and most have minimum earnings or contribution levels, anyone who does not meet those qualifications has an incentive to work more, or earn more, in order to meet them.

Evidence for the US demonstrates the existence of the entitlement effect, and it works in the expected direction. People who live in areas with high unemployment benefits are more likely to take jobs that have earnings exceeding the minimum level required for eligibility. People who live in areas with lower unemployment benefits are more likely to take jobs with earnings below the level needed for eligibility [4]. This positive effect of unemployment benefit schemes offsets at least some of negative effects that might arise from other sources.

Effects on job-seeking and duration of unemployment

A side-effect of unemployment benefit programs is that they may encourage people receiving benefits to search less intensively for a new job than they would have otherwise, for two reasons. The first is that the gain of finding a job is lower for someone receiving benefits, at least during the maximum benefit period. In the absence of unemployment benefits, the gain is simply the wages on the new job. With unemployment benefits that gain is reduced to the difference between the unemployment benefits and the wages paid by a new job because the payments cease when someone becomes employed. In insurance terms this is called moral hazard: individuals alter their behavior after becoming eligible for insurance payments because the programs alter their economic incentives.

A second effect of unemployment benefit programs is that, without it, unemployed workers with few assets would have to reduce their consumption even though it is likely that they will eventually find a job and earn income. Because there is no way to borrow against those future earnings to maintain consumption during an unemployment spell, individuals might have to take a low-wage job or one mismatched to their skills instead of waiting to find a more appropriate job. This is called a liquidity constraint problem. An unemployment benefit program relieves this pressure and allows unemployed workers to maintain consumption without having to accept an inappropriate job.

The distinction between the two reasons that people receiving unemployment benefits take longer to find a new job than they would without the benefits is critical [5]. The moral hazard reason is an undesirable by-product of the insurance program. But the liquidity constraint reason is a desirable consequence. The inability to borrow against future earnings and the temporary pressure it puts on unemployed workers is socially undesirable, and it is a social improvement that unemployment benefit programs relieve that pressure, even while lengthening the time it takes to find a job.

Effect of benefit level and benefit duration

The evidence on the total effect of unemployment benefit schemes on finding a job and on how long that takes is extensive and points clearly to a negative effect on finding a job and a positive effect on how long people remain unemployed. The studies typically examine either the effect of the unemployment benefit level, often in the form of a wage replacement rate, or the effect of the maximum duration of benefits received. On the effects of benefit levels, one study for Austria found that a 4.6% increase in the replacement rate leads to a half week increase in time unemployed [6]. Another study found that unemployment benefits reduced job-finding rates in Austria by about 5–9% [7]. In Germany, where the maximum duration of benefits differs by age, one additional month of eligibility for unemployment benefits increased the period of unemployment by a fairly small tenth of a month [8]. Studies for other countries and groups find effects of similar magnitude.

These effects occur, however, only for those among the unemployed who are covered by unemployment insurance. Unemployed individuals who have newly entered the labor force, who do not have sufficient past earnings or employment to be eligible for unemployment benefit payments, or who have quit their jobs voluntarily, do not experience these effects. The aggregate effect of unemployment benefit programs on unemployment is therefore considerably smaller than the effect on those who receive benefits. In the US, for example, only about a third of unemployed workers typically receive benefits, although the fraction is often higher during economic downturns.

Spillover effects are another reason for a smaller impact on the national unemployment rate than on unemployment of those who receive unemployment benefit payments. Spillover effects occur when a job vacancy that is offered to an unemployed worker who turns it down in order to keep receiving unemployment benefit payments is then filled by an unemployed worker who is not receiving payments. To the extent that this occurs, some of those in the total unemployment pool get jobs they would not have had in the absence of the program. This mitigates any rise in the national unemployment rate.

Another important question is whether the effects of unemployment benefit payments are larger or smaller during economic downturns. On the one hand, during downturns individuals without a job are necessarily unemployed for longer periods because job offers are scarce, and they may be eager to accept the first good job offer they receive rather than extend their time searching just because they are receiving payments. On the other hand, the low number of job offers received may induce individuals to use the unemployment benefit payments to wait even longer to get a good job offer than they would have done in normal economic times.

In Germany the negative effects of unemployment benefit payments are much smaller during economic downturns than during normal economic times and are statistically insignificant in many cases [9]. Extensions of unemployment benefit payments in the US during the recent recession had very small effects on job-finding [10]. These effects were concentrated among the long-term unemployed and often took the form of reduced rates of leaving the labor force rather than reduced rates of entering employment. The extensions had only a small effect on increasing the unemployment rate. In addition, because the extensions most often simply delayed the exit from the labor force, the consequent increases in unemployment did not lower employment to any major extent.

As noted, it is important to determine the relative contribution of moral hazard and liquidity constraints to the effects of unemployment benefit programs on time spent unemployed. Studies found that almost two-thirds of the additional time spent unemployed by people receiving unemployment benefits was a result of liquidity constraints and inability to borrow [5]. A much smaller share of the effect resulted from the socially harmful effects of moral hazard.

Effects of job search requirements

Individuals receiving unemployment benefits are required to search actively for work. Requirements range from simply registering with the governmental unemployment assistance agency, to periodically visiting the agency to discuss search activities, to providing evidence on employers contacted. Programs may call for sanctions for people who fail to search actively, although there is little evidence on the extent to which this occurs.

Studies have examined the effects of relaxing or strengthening job search requirements to see whether that affects the probability of finding a job or the duration of unemployment. Two experimental studies in the US found that job search requirements have significant effects. In one study people who were relieved of all job search requirements were out of work three weeks longer than people with the standard set of requirements and also were more likely to exhaust their benefit eligibility.

In another study people who were required to contact more employers were unemployed almost 6% less time than people who were required to contact the standard number of employers, and people who were told that the unemployment benefits agency would verify their reported contacts experienced almost 7% shorter unemployment time. A study in the UK found a large 30% increase in the probability of finding a job for the long-term unemployed who were told that they had to attend an interview to discuss their job search activity or lose their benefits.

Effects of the method of financing

Another policy issue for unemployment benefit programs is how they are financed. Here the greatest contrast is between the US and most European countries. In the US, unemployment benefit programs are financed by a tax on employers that is based on how many workers the firm has laid off in the past, a system known as experience rating. While firms that lay off more workers generally have to pay higher unemployment benefit taxes than firms that lay off fewer workers, firms are not assessed a “full” experience rating, under which a firm that lays off workers who receive $1,000 in unemployment benefits, for example, would be taxed $1,000 to pay, indirectly, for those workers’ full benefits. In Europe, on the other hand, unemployment benefit programs are generally financed through general payroll taxes.

The reason the method of financing makes a difference is that different industries typically have different rates of layoff. The construction industry, for example, is highly dependent on the weather and on economic conditions and often has to temporarily lay off large number of workers who are later rehired. Most service industries, on the other hand, have much more stable employment. If all industries pay the same payroll tax, then the construction industry is being implicitly subsidized by the service industry, because the construction industry is paying less in taxes than its laid-off workers are receiving in benefits and the service industry is in the opposite situation. This can lead firms in the construction industry to lay off more workers than they would under an experience-rated system.

Limitations and gaps

The evidence remains inconclusive on several important issues related to unemployment benefit programs. One is whether individuals find higher-paying jobs or jobs that are a better match for their skills than they would without the programs. Studies of this issue have reached very different conclusions, with some suggesting no effect and others a positive effect. Additional studies are needed to resolve this uncertainty. A second issue is whether the existence of unemployment benefit programs makes it more likely for employers to lay off workers.

Summary and policy advice

Unemployment benefit programs play a major economic role by increasing consumption among unemployed workers and allowing them to avoid depleting their assets during periods of unemployment. Such programs also have a major positive effect on the households of unemployed workers with few or no assets and no access to borrowing to avoid serious temporary reductions in consumption. Unemployment benefit programs also provide much needed support to unemployed workers during economic downturns, without major side effects in lengthening periods of unemployment or raising the unemployment rate. By helping households with very low incomes, unemployment benefit programs lower the poverty rates. And unemployment benefit programs encourage people to take socially beneficial jobs, despite some risk of future layoffs, which improves the economy.

On the downside, unemployment benefit programs can encourage the unemployed to reduce their job search intensity and to lengthen the time spent unemployed. Increases in benefit levels and increases in the maximum length of time for which benefits can be received heighten these disincentives.

Policies need to strike a balance between the positive goals and effects of unemployment benefit programs and their negative side effects. This can be achieved by setting benefit levels and duration at adequate but not excessive levels. Another important policy tool is to set clear and firm job-search requirements and to enforce them. Having such a set of requirements reduces the negative side effects of unemployment benefit programs without reducing eligibility, benefit levels, or duration.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee, Gary Burtless, Till von Wachter, and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Robert A. Moffitt