Elevator pitch

Women’s labor force participation has rapidly increased in most countries, but mothers still struggle to achieve a satisfactory work−life balance. Childcare allows the primary caregiver, usually the mother, to take time away from childrearing for employment. Family policies that subsidize childcare and increase its availability have different effects on female labor supply across countries. For policymakers to determine how well these policies work, they should consider that policy effectiveness may depend on country-specific pre-reform female employment and earnings, and childcare availability, costs, and quality.

Key findings

Pros

Countries with a higher availability of affordable childcare exhibit high maternal labor force participation rates.

The provision of childcare, especially for pre-school-aged children, helps mothers achieve a satisfactory work−life balance.

Higher childcare subsidies result in a substantial increase in childcare utilization.

Larger labor supply effects occur in countries where employed single parents or two-earner couples are eligible for the subsidies.

Cons

The scope for policy to increase labor supply is limited in countries with very high female labor force participation and/or highly subsidized childcare systems.

Good access to affordable care might result in little or no increase in maternal labor supply if it only crowds out other forms of non-parental care.

Difficulties in measuring the lack of qualified people working in childcare and the quality of care may prevent families from using this service.

Preferences and social norms may drive childcare choices, and not only costs and availability.

Author's main message

Policymakers must identify the most effective instruments when designing approaches for encouraging maternal labor force participation. Investing in quality childcare facilities, especially for young children, can help achieve this goal. Accessibility, affordability, and quality are all important. Women’s pre-subsidy employment statuses, average wages, childcare arrangements, and other factors not directly associated with childcare costs and availability are also important. These indirect factors include childcare regulations, welfare systems, and social norms. All of these factors might strengthen or reduce the effectiveness of family policies.

Motivation

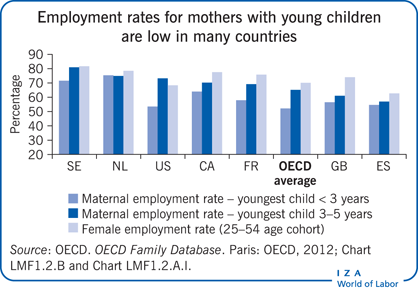

The Europe 2020 Strategy included the objective of having 75% of the population aged 20−64 years employed by 2020. This goal might be difficult to achieve unless it includes mothers. In many countries, the gap is still large between employment rates of women aged 25−54 years and mothers whose youngest child is under age three or between three and five years old. Family and childcare responsibilities are often put forward to explain the low labor force participation rate of women with young children.

Childcare services could help encourage parents—in particular, mothers—to take part in the labor force. However, if such services are not sufficient to meet demand, are too expensive, or are incompatible with the needs of parents (usually mothers) who work full-time—for instance because of inconvenient opening and closing hours, centers being too far away—this could severely affect their work possibilities.

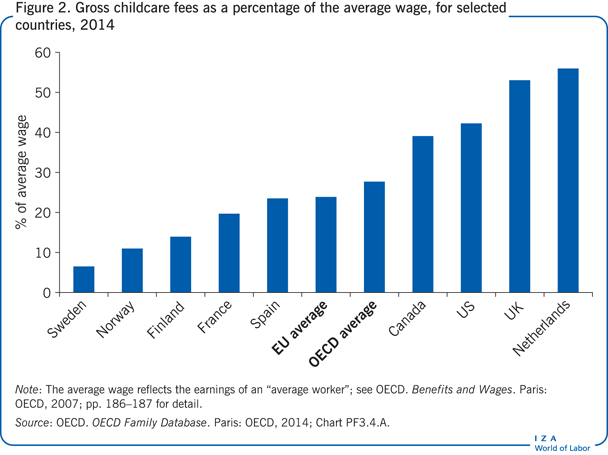

Over the past decade, enrollment in childcare rose considerably in countries that introduced family policy reforms. In other countries, the insufficient provision of formal childcare, especially for young children, is largely responsible for low enrollment. Childcare costs are a further disincentive to entering the labor force. In some countries, costs can take up 50% of the average wage. Family policies that provide sufficient, affordable childcare, particularly to working mothers with young children, could encourage maternal labor force participation.

Discussion of pros and cons

Over the last 15 years, the labor force participation rate (the percentage of the working-age population that is employed, either part- or full-time, or that is actively seeking work) of women of childbearing and childrearing age (between 25 and 54 years of age) has increased in many countries. This has contributed to a reduction in the gap between countries with a historically high labor force participation and countries with a historically low labor force participation. Reforms to family policies, in numerous countries, are among the many possible reasons behind this phenomenon. These reforms include increased subsidies for childcare and the expansion of early education for pre-school-aged children.

The type of childcare provision differs across countries. The three main patterns of care are: (i) the universal and highly subsidized childcare found in Northern European countries; (ii) the public childcare with its low availability especially for children under age three, found in Southern Europe; and (iii) the private, high-cost childcare prevalent in the US, the UK, and Canada, where subsidies mainly target single mothers.

Although many family policy reforms originally aimed to improve child development, they also focused on helping women achieve a better work−life balance. These reforms have varied considerably across countries and over time. Their effectiveness in each country, regarding the maternal labor supply, depends on the availability, costs, and quality of childcare, and the pre-existing levels of labor force participation. In particular, countries whose childcare policies target employed single parents and two-earner couples (as opposed to unemployed parents) have experienced the largest positive effects on maternal labor force participation.

Generous universal childcare provisions are more common in Northern Europe, than in Southern Europe, and low-income families can often access subsidized programs. Consequently, women’s labor force participation and childcare use are also higher in Northern Europe. Southern European countries are instead characterized by low childcare support and low maternal employment. Liberal countries, in particular the US and the UK, are characterized by low childcare support and high female labor force participation. While availability and costs are important, social norms might also partially explain these differences.

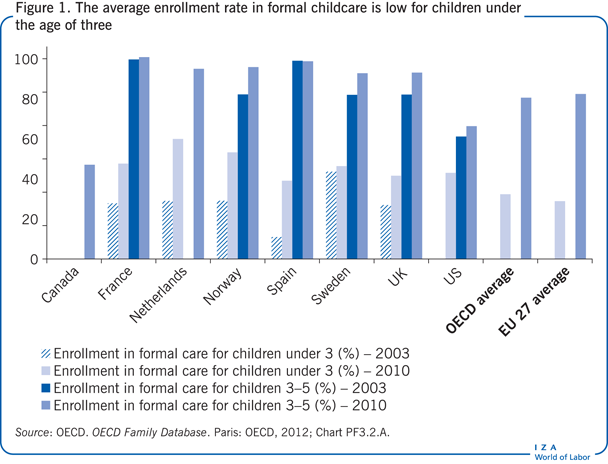

Figure 1 shows the average formal childcare enrollment rate for children under the age of three and children aged three to five years, for selected OECD countries, for 2003 and 2010. While it is evident that the enrollment rate of children aged three to five in formal care does not represent an issue, since it is between 80% and 100% in almost all countries, the low enrollment rate for children under the age of three in many countries, in 2003, was due to the insufficient availability of formal childcare services. The increased enrollments shown for 2010 are the result of family policy reforms that took place throughout the OECD. Significant increases in enrollment are noted for a number of countries. While much of this may be attributed to family policy reforms that have increased subsidies and the number of available childcare slots, a change in social norms over the past few decades may also have contributed, since more women are opting for full-time careers.

It is interesting to compare the female participation rate and childcare enrollment rates across countries. The Illustration shows that the 2012 female employment rates were high for most OECD countries. At the same time, Figure 1 shows the average childcare enrollment rate was low for some of these countries. Part of these differences can be explained by differences in the level of support offered by family policies and by differences in social norms. In some countries, women pursue full-time careers and extend their working hours regardless of the absence of social supports.

Evidence also suggests subsidies cause a shift in childcare use from informal (unsubsidized) to formal (subsidized) care for already working women and, thus, have a limited impact on labor force participation.

The theoretical approach to female employment

Theories suggest that mothers choose between working and using paid childcare or not working and taking care of their children full-time. The income forgone by remaining at home for one hour is the mother’s hourly wage rate (or forgone earnings if she does not work) minus the hourly price of formal care purchased outside the home. Therefore, mothers who earn higher wages will tend to work and purchase formal childcare, while mothers who earn lower wages and, consequently, incur proportionally higher childcare costs, or mothers with strong preferences for home care, will more likely choose to be at home.

Family policies in the form of childcare subsidies potentially affect maternal labor supply. The theoretical predictions of such policies are ambiguous. Consider, for example, the introduction of a childcare subsidy that reduces the cost paid by the mother. This reduced cost will increase her net wage after childcare costs. In this case, for a mother who decides not to work, the subsidy will represent another form of income forgone (in addition to the wage she gives up) by remaining at home. Under this new scenario, if a mother decides to become employed, she will bring home more money than she would have without the subsidy. Therefore, theory predicts that the subsidy should encourage women to enter the labor market, thus raising the participation rate for mothers.

Nevertheless, there is a problem, here, because the potential impact on the number of hours worked by women who are already employed is unknown. For mothers working full-time, the subsidy has a pure income effect. Therefore, if these women decided to work less in response to the subsidy, the subsidy would ensure that they would still bring home the same amount of money. As such, some women might want to work fewer hours, which counteracts the policy objectives.

For women who would have worked only few hours in the absence of the subsidy, it is uncertain as to whether they would substitute the subsidy for their number of working hours and work less or whether they would work more hours for the extra economic gain. Similarly, an increase in the availability of childcare slots or a new public program that grants free access to young children can be considered an additional (in kind) amount of care, with the same clear and unclear predictions.

What do we know empirically about the impact of childcare on maternal employment?

The empirical literature on the relationship between childcare and maternal labor labor force participation is vast and can be divided into two main strands: one evaluates the labor supply effects of increasing childcare subsidies; the other analyzes the labor supply effects of increasing the number of slots or granting universal access to a certain group of children. Sometimes the distinction between the two policies is subtle, since universal access means free childcare for all children who meet the age criteria.

Many countries subsidize the costs of (mainly private) childcare to help parents, especially mothers, return to work after having a child. Subsidies come in many forms, such as refunds to parents, direct payments to providers (reducing costs to parents), or tax allowances for childcare costs. Subsidies may vary by family type, parental employment conditions, family earnings, and the type of service used (e.g. daycare center, family daycare). However, subsidies are usually unrelated to the availability of slots.

Figure 2 shows OECD estimates of the average childcare fees paid for full-time care of a two-year-old child in full-time care as a percentage of the average wage, for selected countries in 2014. It shows that the average cost of full-time care is over 27% of average family earnings, with considerable variability across countries (Sweden and Finland are below 10% of average earnings, the Netherlands and the UK are above 50% of average earnings). In general, childcare subsidies are offered to working single parents and dual-earner families, but they are higher for working single-parent families, mainly due to this more disadvantaged group being targeted.

Earlier studies examined the effect of childcare subsidies on female labor supply. Findings range from estimates of no effect, to significant negative effects, the latter meaning that when the cost of care decreases, maternal employment increases. However, differences in data sources and sample composition (regarding e.g. age, education, marital status) do not appear to account for the variation in the estimates. Instead, two main problems can be identified in these studies: (1) childcare access and costs are directly related to the work choices of mothers and type of care arrangement, and (2) the availability and cost of informal care is often unobserved. When a subsidy for formal childcare is introduced, mothers with children in informal care may opt to switch their arrangement and take the subsidy. If informal care is not properly taken into account and the substitution between formal and informal care is ignored, then the estimated cost effect on maternal employment does not reflect the true effect of these costs.

Since the cost of childcare is frequently not observed in the data, most studies use the average cost incurred by a sample of families who pay for care to predict the cost potentially paid by all families. However, this approach requires the identification of other factors that influence childcare costs but do not directly influence women’s labor force participation. So researchers have typically used local area childcare costs and the average wage of childcare workers as factors that vary across geographic locations but that should not have a direct effect on overall female labor supply. However, using these factors might be problematic if they are correlated with the female labor force participation rate and wages prevalent in a local area, because they might directly influence labor supply decisions. If in a specific region childcare workers’ wages are high compared to the average wage, then childcare costs will also be high relative to the average wage. These higher costs will discourage some women in the region from entering employment and accessing these services.

In recent years, several studies have overcome this problem by exploiting changes in subsidy amounts and availability of slots that vary in time and across regions. These policy changes allow researchers to observe their effects on labor supply. Some studies found a rather small labor supply effect of subsidy reforms for Sweden [1], Norway [2], [3], France [4], and the Netherlands [5]. However, other studies found significant labor supply effects of childcare subsidy reforms introduced in Canada [6], [7], and the US [8].

In 2002, Sweden introduced a cap on childcare prices, which meant municipalities were limited in the amounts they could charge parents. However, the considerable reduction in the cost of care due to the reform had practically no effect on female labor supply [1].

A reform introduced in Norway in 1975 consisted of a large-scale expansion of subsidized childcare for children aged three to six, but produced only a negligible effect on the maternal employment rate [2]. Another study looked at the differences in the cost of childcare across Norwegian municipalities in the 1990s, where some municipalities applied a single cost for all income groups, while in others costs depended on family income. This study revealed similar low effects of subsidies on parental labor supply [3].

More recently, a reform introduced in France in 2004 increased the subsidy to families with children under the age of three, which resulted in a 50% reduction in their childcare expenditures. The subsidy led to a substantial increase in the proportion of families using subsidized childcare, but it led to only a very modest increase in female labor supply. This suggests that the subsidy caused a shift away from the use of informal care arrangements toward formal ones [4].

A complex reform introduced in the Netherlands in 2005 reduced formal childcare fees by 50% for eligible children younger than 12, expanded subsidies to some informal childcare arrangements, and increased public spending on childcare threefold. This reform generated a relatively small increase in female labor supply and a more consistent increase in the average number of hours women worked per week. In this case, mothers who worked full-time or a large number of hours per week seemed to benefit from the subsidies and the subsidized formal care simply “crowded out” informal care [5].

Canada represents an exception to the problem of the subsidy’s limited impact on female labor supply. Quebec introduced a reform in 1997 that provided childcare slots to all children up to the age of four at a parental cost of $5 per child per day. The subsidy increased childcare use and the number of hours of service used, as well as female labor supply. Interestingly, the increase in childcare use was twice the increase in maternal labor supply, suggesting that the subsidies crowded out informal arrangements [6]. The positive effects of the reform on maternal labor supply also persist in the long term when children get older, especially for highly educated mothers [7].

The provision of public kindergarten in the US was also shown to have a positive effect on maternal labor supply when observing five-year-olds in the 1980s. Evidence shows an increase in maternal labor supply in the order of 6−24% of both single and married mothers. A positive effect was also found on the number of hours women worked subsequent to the introduction of this program [8].

Differences in the populations analyzed, the timing of the reforms, the local labor market conditions, and the degree of substitutability between formal and informal care might explain different findings across countries. In particular, in countries with very high female labor force participation or with highly subsidized childcare, further reductions in the cost of childcare have little or no effect, simply because the scope for policies is limited in terms of further increasing labor supply [1], [3], [4], [5]. However, relatively large labor supply effects are found in countries where only employed single parents or two-earner couples are eligible for the subsidies [5], rather than both workers and non-workers [1], [2]. Therefore, the impact of the policy reforms is greatly influenced by the target population and pre-existing labor market conditions (e.g. employment, wages, employment protection). In addition, for some countries, the presence of a well-developed welfare system might explain the negligible labor supply response; when mothers can rely on welfare, this dampens their incentive to work [1], [2].

When the response to an increase in childcare subsidies results in a substantial increase in use, but a small impact on female labor supply, this suggests that formal childcare has replaced other, most likely informal, arrangements [4], [5]. For governments, this limited increase in maternal labor force participation means the net costs of these policy changes seem to be too high to be sustainable in the long term. The costs, in terms of public spending, far exceed the benefits from the new labor market participation created by the reforms. This is because the subsidies are often paid to mothers who are already working, who simply change their preferred care arrangement [5]. In other cases, childcare subsidies do not have any impact on formal childcare use [3]. This is compatible with a situation where there is a lack of available slots. As a result, the subsidy only serves to increase a family’s net disposable income.

Expanding childcare availability has mixed results

Governments can help households reconcile family and work duties by expanding childcare availability, either by increasing the number of available slots or by granting universal access to children who fall within a certain age range. The expansion of childcare availability is shown to have different effects on female labor supply, across countries, depending on the existing labor market conditions, the institutional context, and the childcare characteristics.

A policy experiment that took place in the US from the mid-1960s to the late-1970s, which increased the supply of childcare slots for five-year-olds, showed no effects on the labor supply of married mothers. In addition, single mothers with children aged five or younger did not seem to respond to the policy intervention, but single mothers with no children younger than five did [9].

US Census data for the year 2000 on children enrolled in kindergarten show that employment increased only for single mothers of five-year-olds who did not have additional young children. However, no labor supply effects were found for mothers with children in other age groups [10].

In the 1990s, Argentina implemented a large construction program of pre-primary school facilities to support childcare enrollment for children aged three to five and to boost maternal labor force participation. This program offered free public schooling at the community level, which can be considered an implicit subsidy. It had a large positive impact on pre-primary school participation and maternal employment [11].

Spain also introduced universal full-time pre-primary school for three-year-olds during the 1990s. Some variability in the timing of implementation occurred across states within the country. The reform had some impact on maternal employment: about two mothers entered employment for every ten additional children enrolled in public childcare, and the policy intervention had long-lasting effects for mothers remaining actively employed. More importantly, in this case, there is evidence that the provision of universal pre-primary school did not crowd out informal care [12].

A unique childcare policy introduced in France in the mid-1990s make it possible to evaluate the impact on maternal labor supply of granting access to public school to two- and three-year-olds. Early school availability is found to have had a significant employment effect on single mothers but not on two-parent families. However, the estimated effect of pre-school availability was much smaller for mothers of two-year-olds than for mothers of three-year-olds. This was largely expected, since eligibility for family benefits for non-working mothers expired when the children turned three [13].

As seen for childcare subsidies, differences across countries in the effects of policies on maternal labor supply might be due to the fact that in more recent years and especially in countries where female labor force participation is high or where women work more hours, mothers respond less to incentives (subsidies and/or availability). Women are becoming increasingly career-oriented or are working more hours. For these women the subsidy/free access to publically funded childcare only has an income effect, while the number of (less career-oriented) mothers for whom the childcare policy has both price and income effects has shrunk over time.

Though childcare quality matters, information is difficult to obtain

Some aspects of childcare are easily quantified, such as the price or the number of available slots. Other aspects are equally important for mothers’ employment decisions but are more difficult to observe such as childcare quality. High-quality services may favor its use and, in turn, encourage mothers to work. A center’s low-quality care, even at a reduced (subsidized) cost, would discourage its use. Therefore, policies that reduce the cost or increase the availability of childcare might not increase female labor supply if the quality of care is low.

Unfortunately, information on quality is limited. Some aspects of quality can be observed and easily measured, such as staff/child ratios, group size, education of childcare workers, books, space per child, and a child-friendly environment. Other aspects are more difficult to capture, such as competence of teachers and staff, and motivation and energy of childcare providers.

There is some evidence that parents are either unable to properly judge the quality of childcare services and thus, unwilling to pay for high-quality service, or they do not place a high value on quality care. Even when one of the most easily observed measures of quality is modified, i.e. the staff/child ratio, parents do not seem to respond.

Limitations and gaps

The different responses to policies introduced across countries to boost female labor supply suggest that contextual factors might be important in determining the success or failure of a reform. Childcare choices may not be determined only by financial constraints and/or lack of access to formal care; but social norms might also drive parents’ choices. In countries with strong traditional gender roles, parents may choose not to use public or private childcare, even if mothers work full-time. Informal childcare, provided by relatives, may still be the preferred choice. Thus, if social norms shape preferences, then policy changes may be less effective.

Moreover, even in countries with a relatively low female labor supply, where the scope for childcare policy should be larger, a policy’s effect may be limited without other supportive policies, such as parental leave or greater involvement of fathers.

Summary and policy advice

Many countries have introduced family policies aimed at promoting maternal labor force participation. Subsidized childcare and free access to formal pre-school are two types of policies that would change the budget constraints of mothers with young children and, therefore, should affect their labor supply. However, the evidence on policy outcomes across countries is mixed. Significant effects of childcare subsidies and increased availability have been found for some countries, but not for others. Policies that target children of specific age groups also show mixed results across countries.

Country-specific economic and social factors explain these different outcomes. The effectiveness of childcare policies might be dampened in countries with already high female labor market participation, generous subsidized childcare, easy access to pre-school, a strong social safety net, and/or deeply rooted traditional family values. In some cases, a subsidy might encourage some mothers to enter the labor force but not others. In other cases, it might only encourage women to switch from informal to formal care. In designing policies aimed at increasing maternal employment rates, policymakers need to understand how all of these factors potentially influence women’s employment decisions. Their best option might be to introduce policies that target the population for which childcare costs and availability pose the most significant barriers to entering the labor force.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful comments on earlier draft and Erich Battistin and Vincenzo Atella for helpful conversations.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Daniela Vuri